The Non-Matrixed Wife by Susan O’Neill (Venezuela)

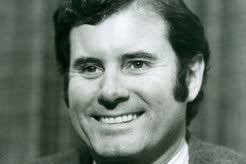

When Joseph Blatchford was appointed director of the Peace Corps in May of 1969 he brought with him a set of “New Directions” to improve the agency. Whether these directors were new or not is endlessly argued, but what was clear was this: Blatchford wanted skilled Volunteers, i.e. “blue-collar workers, experienced teachers, businessman and farmers.”

While the Peace Corps has always found it difficult to recruit large numbers of such “skilled” Volunteers, Blatchford and his staff came up with the novel idea of recruiting married couples with children. One of the couples would be a Volunteer and the other (usually the wife) would be — in Peace Corps jargon — the “non-matrixed” spouse. The kids would just be kids. It would be in this way, Blatchford thought, that the Peace Corps could recruit older, more mature, experienced, and skilled PCVs. And the Peace Corps would stop being just “BA generalists” like the majority of us!

This idea proved to be unworkable, costly, and for the Peace Corps, an administrative nightmare, and by the early 1980s recruiting “families” had ceased. The biggest problem with the scheme was that the non-matrixed spouse had no valid role in the country and without that, he or she, felt useless.

A few of these nonmatrixed spouses, however, came home to tell wonderful tales based on their “Peace Corps experience.” Perhaps the most famous writer from this ill-conceived experiment was Maria Thomas — Roberta Maria Thomas Worrick (Ethiopia 1971–73) — who first went to Ethiopia in 1971 with her PCV husband, Tom, and their four-year-old son. Maria Thomas and her husband would live and work in Africa for over seventeen years and then in the summer of 1989 when they were again living in Ethiopia, and Tom Worrick was the deputy director of the Ethiopian mission of USAID, they accompanied U.S. Congressman Mickey Leland on a visit to refugee camps on the Sudanese border. Roberta went along because she was fluent in Amharic and the mission needed her language skills. During this trip, their plane, a two-engine de Havilland Twin Otter, crashed in the western mountains of the Empire in stormy weather and all nine passengers were killed.

Maria Thomas never wrote about being a non-matrixed spouse, though she did write a wonderful story about being married overseas, entitled, “Come To Africa and Save Your Marriage.”

Now, another gifted writer has recalled her days as a non-matrixed spouse for us. Susan O’Neill (Venezuela 1973–74) was a young mother when she and her husband joined the Peace Corps in the early 1970s, after she had already spent time in Vietnam as an army nurse. Here is her account of being a non-matrixed spouse.–

•

The Non-Matrixed Wife

By Susan O’Neill (Venezuela 1973-74)

“I DON’T UNDERSTAND,” our neighbor said in Spanish. Her face brightened, an Aha! moment. “Oh. You are spies?”

I sighed. I launched, again, into my stock explanation of what the Peace Corps was, what we — my husband and I and our three-year-old daughter — were supposed to be doing in Venezuela as volunteers with the Peace Corps Family Program. She nodded dubiously; I could see she wasn’t buying it. It was a matter of money.

In Venezuela, asking money questions — how much do you make? what do you pay for this apartment? questions that would horrify my mother — was not only okay but de rigueur. And in the University town of Merida, in 1974, when money was abundant and a middle class was emerging, U.S. professors were paid well.

We were not. Why, then, were we there? If not for the pay, what was our higher call to service? From what our neighbor could see, we spent our time checking our mail and drinking café con leche.

This was toward the end of our truncated tour, right before the 1974 Venezuelan elections, and we were indeed doing little more than checking mail and caffeinating ourselves and writing to our Peace Corps representative in Caracas, begging him to assign us to somewhere we could be of use. Our neighbor didn’t witness the writing part, but she knew that her country was rife with spies: all the presidential candidates said it was so. She knew the U.S. had recently killed Allende in Chile even if we didn’t yet know, and she wasn’t blind to the Yanqui-go-home campaign signs painted on the stucco walls of the stores downtown, including that four-story-high, full-color painting by the Socialist candidate’s artists of a dog eating a steak thrown to him by Uncle Sam while a starving kid looked on. “The dog of the rich eats better than the child of the poor,” it said in man-tall Spanish script, and it was undoubtedly true. So . . . we were CIA, right?

In Viet Nam

Four years earlier, I spent a great deal of time trying to explain why I was in-country to people I met in Viet Nam. In that case, my job was fairly straightforward: this was in 1969 and ’70, during what the Vietnamese call The American War, and I served as a nurse in an Army hospital. But I still had to explain why I, essentially a pacifist, was participating in a heart-wrenching war half a world away from my home — especially since women didn’t have to be there.

In truth, I was in Viet Nam because, at 21, I was young and dumb. I had believed a recruiter who plied me with money and the chance to forsake my native Indiana for some exotic place like Germany, Japan, perhaps even Hawaii (but, he promised me, never, ever Viet Nam). I was there because I, who sang protest songs in coffeehouses, had this weird desire to play against type. I had this incipient would-be journalist’s urge to be Where the Action Is. Perhaps I was there because if I was going to be a nurse, I wanted to do something dramatic with it. Hell, I was a kid, only 19, when I enlisted during my senior year in nursing school. Who knows why a kid does anything?

Once I got to Viet Nam, I was helping to save lives. I opposed the war, but I was supporting the troops, which is not, as today’s politics would have it, mutually exclusive.

I met my husband Paul in Viet Nam. Both of us were Army lieutenants: I worked in the Operating Room, and he was the hospital registrar, an administrative job that involved the logistics of transporting patients in and out.

Okay, let’s try the Peace Corps

Our decision to join the Peace Corps in 1973 had much to do with Viet Nam. We both disagreed with the war; we both wanted to travel and use our skills in a different cultural setting, in a country whose people didn’t consider us the Bad Guys. And then, there was Paul’s attitude toward Richard Nixon.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. We married shortly after we got back from Viet Nam, and Paul entered grad school in Educational Administration at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst. We both held down odd jobs and took classes, and we gave birth to our daughter Kym in 1971.

Paul served a semester’s internship in an alternative “school without walls” in Chicago during the winter of 1972. One frozen day, he stepped into a Chicago Peace Corps office; that night, he came back to our apartment clutching a sheaf of application forms for the Family Program.

New directions for the Peace Corps

Records indicate that the Family Program was introduced by the Peace Corps in September of 1969, as a new measure to increase the pool of skilled Volunteers. The Peace Corps would recruit one parent — usually but not always the man, the literature said — to fill an important professional position. The family would come along. The parent without the hot-button job — the “non-matrix spouse,” in PEACE CORPS jargon — would also be trained as a Volunteer, and was expected to find some non-specified type of employment in-country.We filled out our paperwork, delivered it back to the office and waited.

Records indicate that the Family Program was introduced by the Peace Corps in September of 1969, as a new measure to increase the pool of skilled Volunteers. The Peace Corps would recruit one parent — usually but not always the man, the literature said — to fill an important professional position. The family would come along. The parent without the hot-button job — the “non-matrix spouse,” in PEACE CORPS jargon — would also be trained as a Volunteer, and was expected to find some non-specified type of employment in-country.We filled out our paperwork, delivered it back to the office and waited.

And waited.

Paul graduated, and we struck out for Boston to find real work. We heard nothing more from the Peace Corps. I worked as an operating room nurse and Paul found a position as a caseworker for the Massachusetts Commission for the Blind. The job proved to be a dead-end affair. We grew restless. Paul ranted regularly about Nixon’s Viet Nam politics and grumbled that he wanted to “leave the country until the bastard’s out of office.” One day, on his lunch hour, he stopped in a Boston Peace Corps office to ask about the status of the application we’d made nearly a year before.

Bingo. Within two months, in mid-March of 1973, we found ourselves in language and cultural training in Ponce, Puerto Rico. Paul had been selected, because of his Army healthcare background, for the Venezuela Hospital Program. And Kym and I were along for the “non-matrix” ride.

How can I describe our Peace Corps experience? I wrote a long, bad novel based on it years ago; it’s in a trunk in the attic. It’s a comedy. It’s dark. I titled it Weavers In the Fields because I didn’t think I could sell something called Teats on a Bull.

Teats on a bull

Allow me this disclaimer: I know many RPCVs who give value to their programs and the countries they served. I really wish I could count myself among them. Both Paul and I really, really wanted to be of use. But, singer/humorist Kinky Friedman (Borneo 1967–69) claims that during his Peace Corps hitch, he introduced the natives of Borneo to the Frisbee. I can truthfully say he accomplished more than we did in Venezuela.

Maybe our expectations were unrealistic. Consider our background: it’s hard to find a place more organized, productive and useful than a wartime combat hospital. Paul and I were purposeful cogs in a well-oiled machine. Perhaps, in spite of the Peace Corps manual’s admonitions to adjust our expectations to the political realities of our new culture and adapt to its leisurely pace, we still expected organization, productivity, and usefulness in our PEACE CORPS experience.

The timing of our placement militated against this idea from Day One. Venezuela was, by virtue of its petroleum, the richest country in South America, and it had begun to chafe at U.S. control of its oil production and distribution. We arrived during presidential elections, an every-five-year exercise in democracy that had begun in earnest in 1959. Election years were exciting, crazy, with every building of any size painted with slogans and party-sponsored beer blasts packing the plazas. This year, in addition to the usual politics, all major candidates harangued the public with grand plans to wrest the oil industry from the clutches of evil U.S. companies. Neither the sitting government nor its challengers dared look kindly upon Yanquis, even in Merida, our lovely Andean mesa town. And so Venezuela demonstrated no great love of the U.S. Peace Corps.

People were not openly hostile to us; Venezuelans tended to avoid overt hostility — except for our first landlord, but he was pretty much insane (more on that later). The face-to-face confrontation was a cultural no-no; if you wanted to find out how someone really felt about you, you might discreetly pose an indirect question to that person’s cousin’s buddy’s cleaning lady’s daughter. Even so, we could feel an undercurrent of suspicion. It had much to do with our pay, which, as I said upfront, was fair game for discussion.

“So you’re a spy,” our neighbor declared.

“You are with the CIA, yes?” the arepa seller at the café asked. “Only a spy would be crazy enough to work for so little.”

We were amused. We explained. And explained.

People made quiet inquiries about us to North American professors at the university. And the professors, our friends, would vouch for our humanity — but they were careful to establish that they were not professionally involved with us. They didn’t want to appear guilty, by association, of working for the U.S. government.

Working. That was another matter.

Paul’s hospital administration specialty was in high demand, we were told. So high that he was called into the country early before we finished language training. We rushed off to Valencia, to discover that the job he was needed to fill didn’t really exist.

So Peace Corps/Caracas offered us a posting at the Hospital Universidad de Los Andes in Merida.

The Peace Corps manual suggested that each Volunteer attach himself to a local “counterpart,” someone in the Volunteer’s professional field who could introduce him around and help him find how he might be of use. Paul chose a hospital engineer named Manuel, an outgoing, popular guy who spoke very good English. This was particularly important because our aborted training had sabotaged Paul’s shaky grasp of Spanish.

For a couple of months, the pairing worked well. Paul enjoyed the open friendliness of the hospital administration, who applauded his plan to design a fire and emergency safety program — a handy thing for a hospital that sat at the end of the town’s sole, and alarmingly short, airport runway.

Then one day, Manuel disappeared, and the head engineer locked Paul out of the office. Discreet

inquiries made to his cousin’s buddy’s cleaning lady’s daughter yielded distressing news: Manuel was suspected of fencing stolen hospital equipment.

There was absolutely nothing in the Peace Corps manual that covered this, and it came at a difficult time when we were searching for a new apartment because our landlord had evicted us.

Housing in Merida was tight and expensive because the town had to absorb so many university professors and students. When we first arrived, the only affordable place we could find was a converted garage in our landlord’s house. “Converted” meant, essentially, that he had removed the car.

It was a bay with oil stains on the floor, a genuine garage door, and a tiny bathroom. Our landlord lived with his wife, children and mother in the attached house, a two-story building that fronted a small, scruffy plaza. The Morellis were Merideñans born and bred. The wife was shy, the children polite. The mother was a warm, dear soul who stopped by now and then for tea; when all three of us suffered amoebic dysentery, she made us herbal belly-soothers and green-banana soup.

Señor Morelli was a wire of a man, thin and tightly-wound. He avoided direct eye contact and spoke very loudly to us so we could better understand his Spanish. He promised that we would move into the house, into the apartment above his, as soon as the present renters — bad, noisy people who stayed up until obscene hours — moved out. No, he couldn’t show us the apartment, but it was very nice.

The garage was not nice. It was cramped and cold and rattled every time a car passed, but we were living among the people, as the Peace Corps manual had recommended, and we told ourselves it was rather quaint.

A couple of months later, the bad, noisy people upstairs moved out. And we moved up — to find the place filthy and in poor condition. Morelli promised he would paint it and make repairs. Soon; very soon.

We stayed up late our first night scrubbing the place down. Two days later, Morelli called us into his office. We were, he informed us loudly, bad, noisy people who stayed up until obscene hours. “I had such hopes for you,” he shouted.

“We were cleaning your apartment,” we said.

He waved his hand dismissively. Furthermore, he had seen us talking with a neighbor who was a bad person, most likely a thief and possibly a murderer, because “She is not like us, not from Merida, which is the City of Gentlemen; her people are from Caracas.” We were not to be friends with her, he shouted.

Two weeks later, we tiptoed downstairs to ask him about the paint and the repairs.

Morelli told us that Kym had, that fatal very first night, run over the hard floors with her shoes on, and he was a nervous man and couldn’t take it. Forget the paint and repairs; we were to leave, because we were bad, noisy people.

Leave? I was flabbergasted. I apologized for Kym’s shoes and told him we needed time to find an apartment — during which, I vowed, we would be as quiet as the cockroaches that swarmed the bathroom. I handed him his rent money for the month.

He threw it on the floor. “I don’t want your dirty money. I just want you out.”

So while Paul tried to rectify his working experience, I dragged Kym around the town looking for apartments that fit the Peace Corps stipend. We spent as little time as possible at Morelli’s. His wife avoided us; his dear mother hung her head and sighed when we passed.

Eventually, we found an impersonal flat in an inconveniently-located four-story building. It wasn’t exactly “living among the people,” but it was clean and spacious. We later ran into a Canadian professor who told us that he and his family would be renting the apartment we had left. “We haven’t seen the place,” he said, “but Señor Morelli has told us it’s very nice.”

About that time, the professor who tutored us in Spanish came to me with a young mother of five who desperately needed work. The Peace Corps allotted us a small child-care stipend if needed, so I hired Irma to watch Kym so I could find a job of my own.

I couldn’t work officially as an RN; Venezuela didn’t recognize my registration. Still, I was eager to be of service; I thought that perhaps I could give the operating room in the hospital the benefit of my Army training and experience free, as a volunteer.

The head of the OR received me cordially and gave me a proud tour of the surgical area, and I determined I could help by writing a manual of Standard Operating Procedures for them. This is a notebook that details such necessities as the special tools each surgeon likes to have in his sterile instrument set-ups. Every OR in which I’d worked relied heavily on its SOP manual; a busy nurse need only glance at it to know what to bring into the room for each particular case.

So I watched surgeries and took notes for the book, and people seemed proud of their work and happy to see me appreciating it.

Then I made the mistake of reacting when a nurse dumped an instrument straight from a cardboard product box onto a sterile instrument table.

It took me by surprise. In nearly every way, this operating room seemed like any OR back home. Staff scrubbed, gowned, masked and gloved. They assiduously avoided contaminating sterile things. But here was this nurse, carefully holding her body away from the table, with its glittering sterile instruments, opening an un-sterilizable cardboard box and dumping a contaminated instrument on top.

She later showed me a little white pill that, when dropped in to the box, would render its contents sterile. The pill was indeed a solid form of a chemical we used back home in a special gas device to sterilize delicate instruments that couldn’t stand the more corrosive steam under pressure. But dropped in a box, it had about as much power to sterilize as an aspirin. She needed the machine to make it work.

I said nothing, but my stomach dropped into my feet. This was my dilemma: If I were to try to requisition the sterilizer and teach the staff how to use it, I would be insulting them — because they were the trained professionals, and I was a gadfly from a foreign country who by law was not even allowed to work in the field for pay.

Whatever plan I might’ve made, I had already sabotaged it. I had reacted, however involuntarily, to the dropping of that instrument. The insult was there already, lurking in my raised eyebrows.

I humbly went back to my notes, to the SOP book they would surely find useful. But the atmosphere grew frosty. Within a week, I didn’t have to ask anybody’s cousin’s buddy’s cleaning lady’s daughter where my self-assigned project stood.

The Five Year Plan

By this time, Paul had regained access to the engineering department, thanks to a hospital board member, who had leaned politely but pointedly on the head engineer. Our cousin’s-buddy’s-cleaning-lady’s-daughter source informed us that the head engineer had despised Paul’s erstwhile counterpart, and was simply showing his disdain for Manuel by locking Paul out. I had free time now, so I joined Paul in Phase One of his project.

The hospital was a victim of Venezuela’s peculiar five-year election syndrome. It had been planned eight years earlier, on a promise from a newly-elected president. But after an election, it was an informal custom that nothing momentous happened for three years — so it had been left to languish. Then, two years before the next election — again, according to informal custom — the ruling party demonstrated its intent to improve life in Venezuela with a building frenzy. The hospital was hastily and partially slapped together. But the ruling party lost, so for the first three years of the new leadership, the hospital again lay not-quite-finished. Then came the frenzied preparations for the current election, and it was completed — with little regard for the original architect’s plans — and opened as proof of this government’s goodwill.

Paul’s fire and emergency system would require those using it to know where all the exits and equipment closets and traffic paths were, and they were not where they’d been on the original blueprints. So Phase One meant redrawing the plans. For this, Paul carefully measured the hospital’s corridors, doors, stairwells and so forth. It was a good job for two people because he needed someone to hold the end of the measuring tape. He then took the day’s notes to Town Hall, where he could use a fellow Peace Corps Volunteer’s architectural table and tools to redraw the blueprints on big rolls of tracing paper.

I had been helping for a week or so when our former landlord showed up. His manner was surly, offended; he refused to look Paul in the eye as he demanded his rent.

Morelli had rejected our payments not just once, but three times — Irma the babysitter told us this was intended to be a great insult. Paul told him that he had tried in good faith to pay, and that was sufficient; he was not going to pay now.

Another week passed, and we received a letter from Morelli’s lawyer that informed us we were being sued for three times the amount we owed.

Once we deciphered the arcane Spanish legalese, we were terrified. A lawsuit! Could we be imprisoned? Deported? We hurried the letter to a Venezuelan friend who tsk-tsked over it and gave us a lawyer’s name.

The lawyer looked us over solemnly, then called Morelli’s lawyer. They chatted for a half-hour, enquired after each others’ families, laughed, traded jokes. He hung up and informed us he’d managed to winnow the price down to the original rent.

We paid.

Paul and I continued to work on the hospital plans. Lawsuits aside, things seemed to be looking up; perhaps, after all, we were going to be of use.

And then one day, Irma didn’t show up to babysit. We had no phone and didn’t know where she lived; we were worried sick that something might have happened to her. Kym had grown to love her and she, too, was frantic.

That evening, Irma’s 12-year-old son knocked on our door. His mother, he told me, was taking part in a barrio invasion and might be gone for many, many days.

In Venezuela, land or property left unoccupied may be claimed by “invasion” — people simply squat on it and refuse to leave; eventually, it becomes theirs. There was a housing project that had remained not-quite-finished due to the vagaries of the election syndrome, and Irma and some of her neighbors, who lived in a very poor part of town, decided to claim it. In an election year, someone would surely promise them running water and electricity, if they remained long enough. “Long enough” could mean months.

And so we lost her. I took Kym to the office when I could to help with the few remaining touches of Phase One. Soon, the new true-to-the-building plans were finished.

They looked wonderful. Professional. We were both proud of them. Paul presented them to the hospital CEO for his inspection. The CEO received them with great ceremony, and Paul left the office feeling that he had done something positive and meaningful, energized to move on to the Fire and Emergency logistics of his project.

The next day, the janitor who worked the offices — a man Paul joked with whenever they crossed paths — brought him the rolled-up floor plans. He had found them, he said, in the hospital CEO’s wastebasket. He knew Paul had put a lot of work into them, so he thought perhaps he might want them back.

Peace Corps flexibility

By now, we were finding it hard to remain amused. We contacted Peace Corps/Venezuela. We had tried, we said; the political situation was growing more unhelpful by the day. Wasn’t there someplace, anyplace, they could send a hospital administrator and a nurse where we might actually be of use?

Wait until after the election, they told us. Things would open up then.

So we took Kym to the zoo and hiked the mountains and checked our mail, visited other Volunteers, drank Polar beer in the tents set up in the plaza by one or another of the political parties, or café con leche in the local coffeehouse. The times were exciting; it was not a bad life. But we were not useful. I found myself making unfair comparisons between this flojo Peace Corps existence and the efficiency of the War Corps, and concluded unhappily that, if Venezuela was any example, the War Corps was far more effective at what it did.

Sadly, our lack of productivity was not unique. In Merida alone, we had a Sports Program Volunteer who taught English occasionally to a nun, while his wife taught dancing to one of the nun’s students. Another Sports Program man had moved seven times, trying to be of use; he now spent his remaining four months mountain-climbing, playing banjo and weaving hammocks. An engineer also taught nuns English — it seemed to be the one job that would accept Peace Corps Volunteers, perhaps because we did it for free.

A town away, there lived a couple who had trained to teach farmers how to farm more effectively. They had learned via the cousin’s-buddy’s-cleaning-lady’s-daughter route that local farmers didn’t take them seriously — they were too young, too inexperienced. We were griping about our situation with them when they suggested use for Paul’s blueprints: they needed decorations for their living room wall. So . . . what the hell. For all I know, those plans might still be hanging in that little farmhouse in Ejido.

We were off touring Colombia in December when Venezuela elected its new president — Carlos Andres Perez, whose party was not the one previously in power. We returned and again spoke to Peace Corps/Caracas. Wait, they told us. Things will improve. Also, they would check with Peace Corps/Washington to see if we could transfer to another country where Paul’s skills could be used.

So we waited. We threw a terrific Christmas party for our friends, neighbors and fellow Volunteers, where our Sports Program friend played the banjo. We hiked, drank more coffee, wrote more letters. January came and went, but there was no new posting.

In fact, to our amazement and despair, more Volunteers had come to Merida. Eight of them, including an arts and crafts guy, a sociologist working in agriculture, an urban planner, an architect — the only replacement in the group, he was to take over from our friend at Town Hall, whose table Paul used for his project — and The Bear People, so nicknamed because their project was to track some kind of bear in the mountains (The Sports Program banjo player said, “They’d better pitch their tent in the zoo and get a good look at the one they got there. I’ve been trekking all over these hills for months, and I’m sure that’s the only damned bear they’re going to see here.”).

February brought Kym’s third birthday, but no new posting. Another party, more hiking, coffee, letters. Wait, said Caracas. Staff changes are coming; things will improve. If not, there’s still that transfer. And we waited, bored and restless.

March arrived, and the Peace Corps/Caracas staff came to Merida to meet with all us Volunteers. It was an acrimonious session, the Volunteers accusing the staff of unresponsiveness, the staff pleading for patience from the Volunteers. We asked about our transfers and this time when they told us to wait, we decided we had waited long enough. And sadly — because we really had wanted to be of use — we left Venezuela.

Nixon, I might add, was still in office.

In, Up, and Out!

That was 30 years ago. Venezuela has not prospered since those heady days when it took back its oil industry. It has fallen prey to massive currency inflation. The rich remain rich; the poor have gotten poorer, and the middle class that we saw emerging has slipped away. It suffered a coup attempt, and the current president — who led the coup — is a controversial figure. The Peace Corps left for good in 1977, fifteen years and 2,134 volunteers after it first arrived in 1962.

We, on the other hand, have prospered. Paul holds a good job in the Healthcare field, and I write — which may or may not be considered of use. Kym is an adult with her own family now. All of us, Paul and I and Kym and her two post-Peace Corps brothers, are responsible citizens and ardent world travelers.

For Paul and me, and perhaps for our kids, this will to travel is a legacy of both the Peace Corps and the War Corps.

My time in Viet Nam, while harrowing, made me desperate to see the world beyond my borders — precisely because we were allowed to see so little of it there. We were cloistered from it, tantalized by it, justifiably paranoid about passing through it. Build a fence, and you give people the compulsion to climb over it.

Our time in the Peace Corps gave us a good, long look at a different culture from ground level, if not truly from inside. The good, the bad, the silly, the political, the downright weird (often indistinguishable from the political) — we swam in it every day, hiked its mountains, drank its coffee, spoke its language and hobnobbed with its people. We didn’t help Venezuela, no. We were teats on a bull — but what a fascinating bull. It taught us, a family of white, privileged Yanquis, how it feels to live as a not-quite-trusted minority. We learned — often from someone’s cousin’s buddy’s cleaning lady’s daughter — how we appeared to others, how we did indeed represent our government even when we might have preferred not to.

Looking back from this distance, I can say that what I got out of our less-than-productive experience was, as the commercial says, priceless. It is a part of me; it colors my appreciation of the complexity of my fellow man, the way I see my small position and the larger position of my country, and the still larger position of my government, in the world.

For that, I am tremendously, if belatedly, grateful.

•

(First Published on Peace Corps Writers in the 1990s)

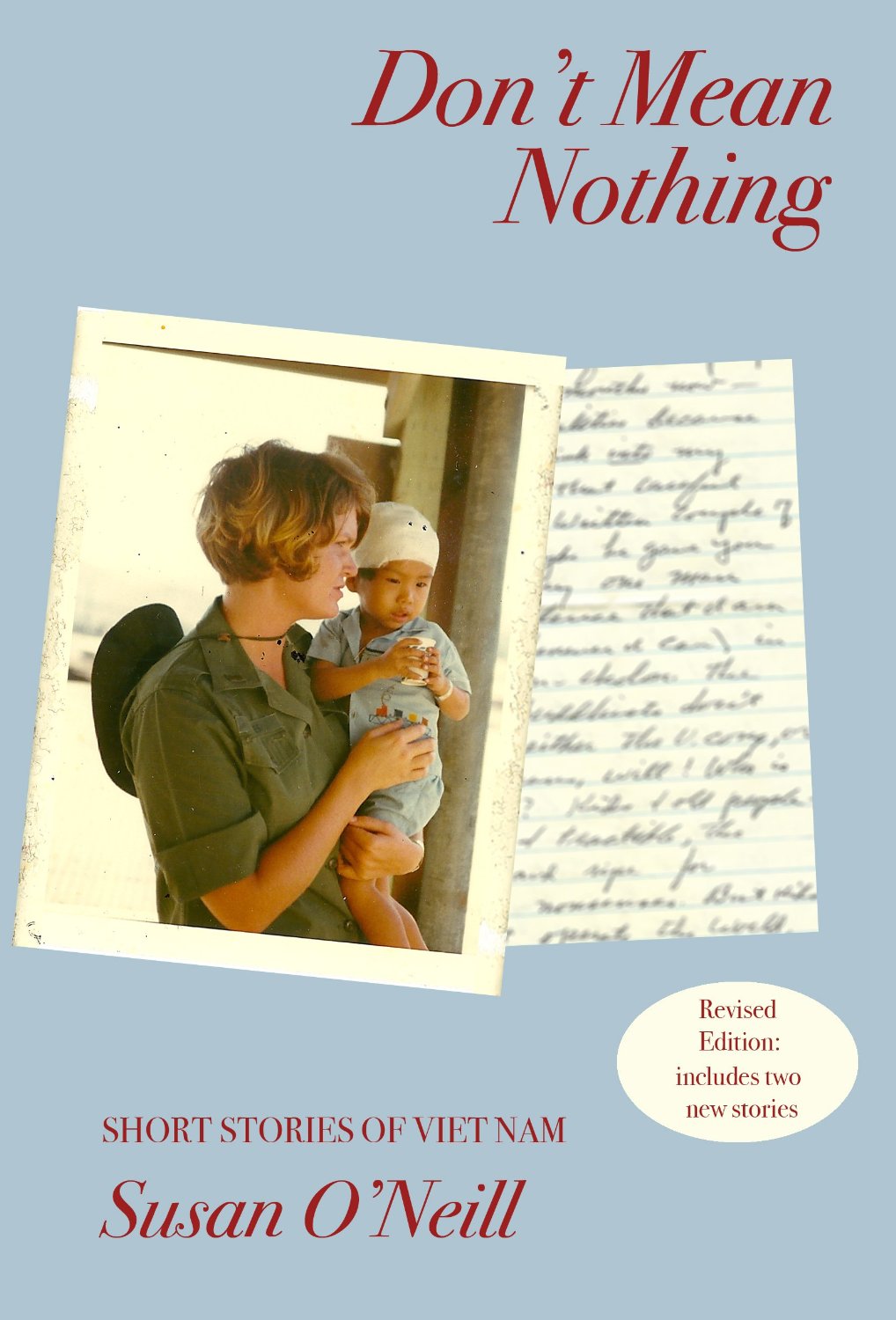

Susan O’Neill has been an RN since 1968, an Army veteran since 1970, and a writer since she could hold a  pen. She is the author of Don’t Mean Nothing: Short Stories of Viet Nam, published by Ballantine and, now in paperback, by UMass Press; it has received only one bad review, which called it “M.A.S.H., with lots more sex and cursing.”

pen. She is the author of Don’t Mean Nothing: Short Stories of Viet Nam, published by Ballantine and, now in paperback, by UMass Press; it has received only one bad review, which called it “M.A.S.H., with lots more sex and cursing.”

She has published in magazines, some of which pay in money and some in copies, and has an epic novel currently being rejected by major publishing houses.

She and her husband Paul live in Andover, Massachusetts in loving fear that one or more of their three children will move back into one of their spare bedrooms.

That bio is the best I’ve read since Erma Bombeck’s book titled “When You Look Like Your Passport Photo, It’s Time to Go Home.”

A wonderfully told tale of the realities of life in the world. Thank you.

Enjoyed it!

Susan’s account rings true to me having served with the Peace Corps in Venezuela 1968-1970. In fact, after all these years, I can still identify with and laugh out loud at her many trials:). We were more fortunate. My wife and I served in an agrarian reform colony (Caimital) in the hot lowlands of Barinas where poor farm families had so many basic needs, that we found plenty to do- most of it essentially “non-matrix” stuff:) The drinking water was all bad, infant mortality was high, people lost time and income due to lingering infections, people suffered machete cuts, snake bites and pesticide poisoning. We could have definitely used her and her husband’s help as we developed and gave first aid classes, helped the community successfully pressure for and get a clean water supply and to bring a small clinic to life, and hauled the dead and near dead to sure death at the local hospital or straight to the graveyard.

I might add that our group was almost all married couples, most of whom left before their assignments were over. At our end of tour conference, we recommended that the Peace Corps withdraw from Venezuela…..the country had the people and resources to do what we were doing but lacked policies and incentives to do it. Thank you for sharing and for the grace, humor and perspective to move on without bitterness.

I might add that I later worked as a Peace Corps staff member in Belize and Honduras, with my primary goal as seeing that each and every volunteer had at least a fighting chance of having a rewarding experience. It usually worked out that way.

I look forward to reading “Don’t Mean Nothing; Short Stories of Viet Nam”. You might enjoy a short novel I wrote which builds off a Peace Corps like experience gone awry in Venezuela.. Its gritty, not for the faint of heart! “Devil’s Breath” by Robert Thurston on Amazon.