The Peace Corps experience changed lives (Burkina Faso)

MAY 25, 2023They came from all over the United States and were going to live in a foreign country for two years where most of them didn’t speak any of its languages.

Susan and Jim Hyde are third and second from the right in this photo from Pacific Grove, which is just south of Monterey, Calif., where 28 of 40 Peace Corps volunteers to Burkina Faso in 1967 joined for a reunion this spring.

They were enthusiastic and idealistic. They were in their early 20s and had recently graduated, lots from Ivy League Schools. Some of them had teaching, clerical or administrative work experience. A few had done manual labor. In their bios for the Peace Corps, lots of them said they liked tennis and skiing.

It wasn’t in their bios, but it goes without saying: They all were going to change the world.

Maybe they did. It’s interesting to ruminate on how the world might be different if there had never been a Peace Corps.

Jim and Susan Hyde of Charlotte were part of a group of 40 Peace Corps volunteers who were sent to Upper Volta in 1967. It was a time when so much was new. The Peace Corps had just been started in 1964 by John F. Kennedy, the darling of that era’s optimism. Upper Volta had only recently thrown off the shackles of colonialism, becoming completely independent of France in 1960. In 1984, Upper Volta became known as Burkina Faso.

Over the years, the Hydes have remained close with the other volunteers who went to help in the former Upper Volta. In fact, they’ve just returned from a spring reunion in Monterey, Calif. Of the original group of 40, 28 attended the reunion. There have been several such reunions since the late 1960s.

A few years after returning, Jim and Susan Hyde began to date. They’ve been married for over 50 years.

The Hydes say they were changed by their two-year experience in the landlocked country in west Africa. Like most of the Peace Corps volunteers, they knew very little about Africa, little about the country they were being sent to and even less of its languages.

Almost all of the volunteers came back to the United States determined to commit their lives to some sort of service.

“There’s not very many of us that are investment bankers or private lawyers. Everybody went into things that have some obvious social engagement involved,” Jim Hyde said.

An agricultural school from 50 years ago that students attended until about the fifth grade, learning reading, writing and what were “modern” farming techniques at that time.

When the Hydes were in Burkina Faso, the schools had almost no books, supplies or tools to demonstrate techniques and relied upon the ingenuity of the teachers, who did an amazing job with very little. Rural education has certainly improved since then.

In the years since, Hyde served in public health and nutrition, work which took him back to Africa a number of times, working in areas around Niger and other countries to its east and South Africa.

But neither he nor Susan have been back to Burkina Faso.

“The Peace Corps no longer can function in places like Burkina Faso because it is too dangerous,” Jim Hyde said. With the United States and France seeming to have lost interest, “global politics have entered the lives of people in ways that it was hard to imagine 50 years ago.”

Muslim fundamentalists have begun to exert influence in countries in the area such as Mali, Niger, Chad and Burkina Faso.

About a third of the people of Burkina Faso are Muslim but far from fundamentalist, or at least weren’t when the Hydes were there. About a third are Catholic and the other third are animist with no organized religion.

Russia and China are also working to exert influence for geopolitical and economic reasons. Besides wanting more world power, those two countries value the area for its mineral resources.

“Mainly, it’s all about electric cars and lithium, uranium and everything else — not because anybody cares much about the people,” Jim Hyde said.

Russia, in particular, has sought to increase its power the area, while gaining support in the U.N., through the use of proxies such as the Wagner Group, which has been helping prop up authoritarian governments in many of these countries, he said.

The Wagner Group is a private paramilitary organization that Russia has used in military operations.

Other members of the Hydes’ group of Peace Corps volunteers did go back to Burkina Faso. They have established programs to support such things as women’s education, well drilling and artists and crafts co-ops.

“It’s a drop in the bucket, but it’s a start,” Jim said and shared these two links to help: Friends of Burkina Faso and Burkina Faso Girl’s Education.

Their Peace Corps experience was a startling experience for both of them. Susan Hyde grew up on a farm in a little town. She went to a relatively big city of 10,000 in Burkina Faso, while her future husband was from Manhattan and was sent to a village of 200.

Many of the chiefs had pretty good French from their experience fighting in Europe during World War II.

With her bachelor’s in history from Swarthmore, Sue Hyde didn’t know much about maternal and child health, but that was what she worked on, going out to smaller villages to meet with women. They would weigh babies and do shows to illustrate nutrition, wellness and what to do if a baby had diarrhea or if a mother couldn’t breastfeed. The polio vaccine had only been out for a short time and hadn’t reached the hinterlands of the country, so she helped with polio vaccine drives.

They had to straddle a very wide cultural and experience gap, Susan Hyde said. “The women were used to listening to their mothers and grandmothers, not to white women who had never had children.”

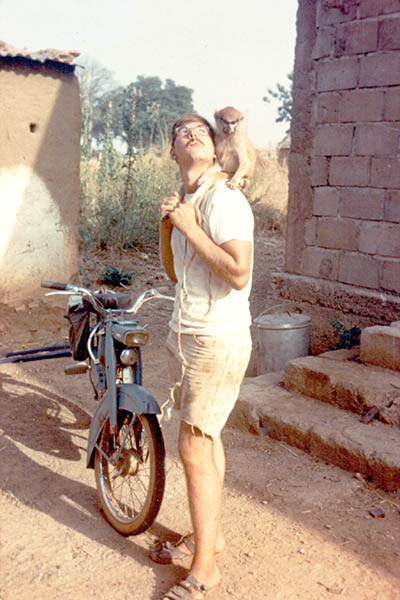

Jim Hyde and Marvin, a monkey he purchased to keep him company in the small village in Burkina Faso where he worked to get wells dug.

Much of Jim Hyde’s time in Burkina Faso was spent on a motor bike driving in the bush on dirt roads which were not as good as Charlotte’s gravel roads. He would visit three or four villages a day, trying to convince village chiefs of the advantages of organizing a group of men to dig a village well. He would talk them into gathering sand and gravel that could be mixed with cement so that when the well was deep enough the walls could be covered with concrete.

They dug the wells with shovels, some of which were more than 100 feet deep and might take two or three months to dig. Many are still standing, protected from the rain by their concrete walls.

“It was a very concentrated experience. There was no escaping your life,” Susan Hyde said. “There was nothing to do.”

No TV, bars or some place to get a drink, no soccer arenas. No cars.

They did have books. The Peace Corps gave each volunteer a locker with 300 books. There were three different versions of the book lockers, so when they had read all their own books, they swapped books with someone with a different selection.

And they got to know each other and the people of Burkina Faso pretty well.

Jim Hyde said, “The only option was to just became totally acculturated.”

The well diggers had even less access to the other Peace Corps volunteers because they were spread around the country in small groups. Jim started out in a group of three which was eventually split up and sent to live in different small villages.

Monkeys are not indigenous to Burkina Faso, but he bought a monkey and named him Marvin. Although they were constant companions for a year and half, Marvin wasn’t the best partner. He wasn’t cuddly and occasionally bit visitors.

Jim discovered that his monkey had another bad habit. His motor bike had started running rough and had become hard to start. One day he saw Marvin take off the gas cap and pee in the tank. Jim Hyde bought a screw on cap and the bike ran great.

When he returned to the United States, he had to leave Marvin behind. He suspects the villagers may have eaten the monkey after he was gone.

The Peace Corps was a life-changing experience. It’s hard not to be shaped by the experience of witnessing people working daily to survive and provide for their families. Jim Hyde said, “Nothing comes easy — not water, not food, not education, not health care.”

Susan Hyde said, “My Peace Corps experience has been the lens through which I interpret the books I read, the events I attend, the volunteer work I do and the people I meet. Experiencing and living in a culture so different from my own allows and requires me to see world news and events from many points of view.”

There are lots of Peace Corp volunteers around Charlotte, Jim Hyde said. The ones he knows all brought back a commitment to thinking of ways to share knowledge and promote understanding of the part of the world where they served with Americans whose lives are “incredibly insular.”

“We use the term Africa as if it were one place when in fact it is composed of 48 countries on the continent plus six island nations, as different as Alaska is from Florida,” he said.

Their story is of one of those countries 50 years ago, Jim Hyde said. Although much has changed, much has stayed the same.

“What hasn’t changed is the diversity of people, geography, language and culture,” he said. “The other thing sadly that hasn’t changed in 50 years is our general lack of understanding of, or interest in, African affairs. We are further imperiled by our seeming lack of interest and concern for what happens on the continent.”

Terrific experiences , wonderful that he wrote such a detailed reflection.