Talking With Danusha Goska (CAR & Nepal)

An interview by John Coyne (Ethiopia 1962–64)

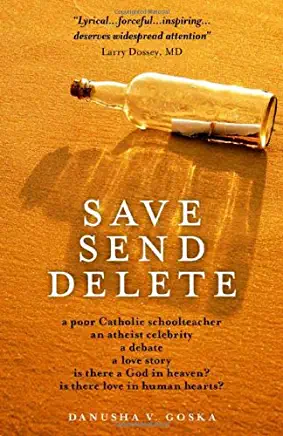

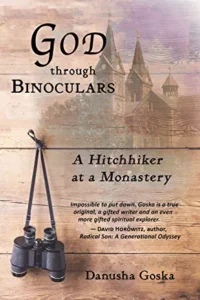

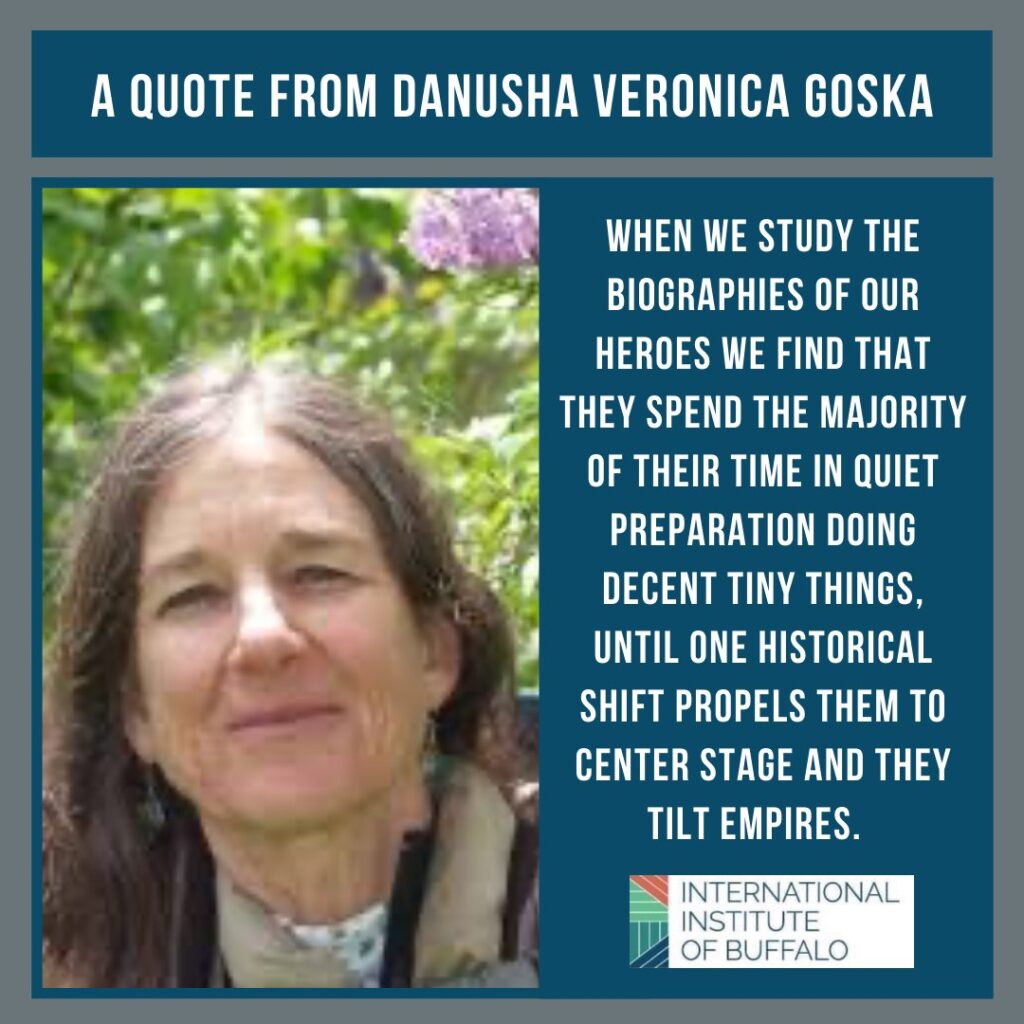

Danusha Goska (CAR 1980-81) and (Nepal 1982-84) was born in New Jersey to peasant immigrants from  Poland and Slovakia. She has lived and worked in Africa, Asia, Europe, on both coasts, and in the heartland of the US. She holds an MA from the University at California, Berkeley, and a PhD from Indiana University, Bloomington. Her writing has been awarded a New Jersey State Council on the Arts Grant, the PAHA Halecki Award, and others. Her book Save Send Delete was inspired by her relationship with a prominent atheist. In 2018 she published God Through Binoculars: A Hitchhiker at a Monastery.

Poland and Slovakia. She has lived and worked in Africa, Asia, Europe, on both coasts, and in the heartland of the US. She holds an MA from the University at California, Berkeley, and a PhD from Indiana University, Bloomington. Her writing has been awarded a New Jersey State Council on the Arts Grant, the PAHA Halecki Award, and others. Her book Save Send Delete was inspired by her relationship with a prominent atheist. In 2018 she published God Through Binoculars: A Hitchhiker at a Monastery.

Danusha, you did two tours as a PCV. What were your assignments?

I was assigned to teach TEFL, English as a foreign language in the CAR and Nepal.

What did you bring away from those tours? Were they alike?

The most overwhelming fact I brought away from living in the Central African Republic (CAR) is how hard life in Africa is. I rarely talk about Africa with Americans because I assume that they can’t wrap their minds around it.

I become enraged when I stumble across scientific racism that insists that test scores prove that black people are intellectually inferior. I want those who make negative assumptions about black Africans to live in sub-Saharan Africa and see how long they survive.

The year-round heat changes human culture. Winter is a gift to temperate climates. In winter you must store food, for example. Winter lowers vermin numbers. Winter demands permanent housing. Winter changes human outlooks.

Danish Goska

Equatorial countries that are always hot lack the gifts winter offers. Food storage is a major challenge in CAR. The heat supports so many different life forms, from microscopic ones to insects to venomous snakes and dangerous large animals like crocodiles and hippos. Once I put a tightly wrapped cube of “Laughing Cow” on a shelf and within hours it was covered with ants. Once I went for a very short walk at night and felt stinging on my legs. I had stepped into a long line of army ants. We were not to step into streams or touch water that hadn’t been boiled because of schistosomiasis. We were told to iron our clothes, for fear of insects that might lay eggs on the clothes. The house I lived in was the home to hundreds, maybe thousands of bats whose urine and feces trickled down the walls. No matter how clean you were, rats and cockroaches were everywhere. There’s no winter season that kills off vermin.

Central Africa is a disease hot spot. There were drug-resistant strains of TB as well as malaria, polio, and every kind of internal and external parasite.

CAR had been preyed upon by the slave trade and it was depopulated. CAR has gold and diamonds and other natural resources so of course more advanced countries preyed on CAR to gain access to raw materials. That happened under colonialism and it’s happening now with interference by Russia and China.

There was an attempted genocide of Christians in CAR by Muslims. Christians then retaliated and began to kill Muslims.

There’s no governmental structure powerful enough to create and maintain stability.

When I think of CAR, I think of how very, very, very hard life there is. I despair at any ignorant person who judges sub-Saharan Africans for being poor and under-developed. It’s not about genes. It’s about circumstances and how those circumstances fashion human culture. Landlocked, equatorial Africa countries are very, very tough places to live, and anyone tempted to judge the people living there should go live there and see how long they last.

Nepal was as different from CAR as CAR and Nepal are different from the US. Both Nepal and CAR were incredibly poor, and by poor I mean places where unfortunate people die for lack of adequate nutrition.

Nepal was as different from CAR as CAR and Nepal are different from the US. Both Nepal and CAR were incredibly poor, and by poor I mean places where unfortunate people die for lack of adequate nutrition.

Nepal is in the Indian subcontinent, and, as such, it shares in Hindu civilization that is thousands of years old. Northern, high-altitude Nepal shares in Tibetan Buddhist culture. Society is structured rigidly. The caste system places some above and some below. Nepal is of course the home of Mount Everest and its mountainous terrain results in micro climates and sometimes micro cultures. High up the weather can be very cold. Lower down it is hot year round.

Nepal is a spectacularly beautiful country. The beauty can be so overwhelming that the beauty dominates my memories.

Was there one moment or situation that sums up the experience in the Peace Corps for you?

One day I was walking from one village to another. As the crow flies, the two villages were maybe five miles apart, and five miles is not much of a walk. But this is Nepal, and to traverse the distance I had to walk down thousands of feet, and then walk up a few more thousands of feet of very steep trail winding through jungle.

This was monsoon, and it began to rain. I had a tarp I had purchased at an American camping goods store. It was pretty much useless against monsoon rains, but I used it anyway, draping it over myself and my pack.

I came upon a landslide. The slide was not particularly large by Nepal standards. I had traversed landslides that stretched for over a mile. This landslide was fresh and no previous walkers had established routes around it, so I had to bushwhack my own route. Again, it was raining, and night was falling. By the time I had bushwhacked my way around the landslide, I was completely disoriented. I just chose to walk along the best, most heavily cleared trail I could find, knowing I would eventually make my way to human habitation.

After night had fallen, up ahead, I saw lights. It was a typical Nepali peasant village dwelling, fashioned of mud, wattle, and straw. The lower part of the tiny, one-room house was daubed with red ocher; the upper portion was shiny with white lime. A thatched roof. A wooden porch in front, for drying grain. A charpoy, that is a traditional cot constructed of a wooden frame and woven straw top sat out in front. The door was open. I could see the family inside. They were eating popped cow corn, their only dinner for the night. Nepali popped corn is not like American popcorn. Most kernels don’t pop, they just scorch. Eating this corn requires good teeth. Such corn is a typical Nepali dinner. It’s what poor people eat, and a disparaging Nepali insult term refers to people who eat corn. It’s a way of saying, “You are poor, you corn-eater.”

By this point it was full night. I just sat down on the porch outside. I said nothing. I was exhausted.

I could hear the family inside speaking. They spoke Nepali, of course, which I spoke and understood. They were saying, “There is someone on the porch. We have to cook rice.” By “rice” they meant a full dinner of rice, lentils, and vegetables, perhaps with a side order of pickled vegetables.

They had no idea who I was. They could not see me, except as a human form on their porch. I had said nothing to them. And their first instinct was to put aside their own humble meal and prepare what, for them, would be an elaborate meal of their best available ingredients.

Growing up did you always want to be a writer? Did you even think about writing books?

Yes. Always.

What were you trying to achieve with your book God Through Binoculars: A Hitchhiker at a Monastery ?

I wrote God through Binoculars in an attempt to re-enter life. My sister Antoinette was diagnosed with glioblastoma in 2013. As soon as I received the phone call from her daughter reporting to me that she had been “driving erratically” I knew that she was going to die. Eventually the diagnosis came down and the doctors just reinforced my intuition. For the next two years I did everything I could to support her. She was my older sister and a dominant personality and it was not easy to go from a lifetime of deference to her to changing her diapers but it’s what the situation called for. On April 10 – Siblings Day! – in 2015, I was rubbing her feet as she died. I was overwhelmed by sadness and I miss her everyday.

I wrote God through Binoculars in an attempt to re-enter life. My sister Antoinette was diagnosed with glioblastoma in 2013. As soon as I received the phone call from her daughter reporting to me that she had been “driving erratically” I knew that she was going to die. Eventually the diagnosis came down and the doctors just reinforced my intuition. For the next two years I did everything I could to support her. She was my older sister and a dominant personality and it was not easy to go from a lifetime of deference to her to changing her diapers but it’s what the situation called for. On April 10 – Siblings Day! – in 2015, I was rubbing her feet as she died. I was overwhelmed by sadness and I miss her everyday.

I knew it was my job to continue living. I had to figure out a way to do that.

Back in 2005, I had undertaken a silent retreat to a remote Cistercian monastery in Virginia. My plan was to present God with all the big questions. In fact this “silent” retreat ended up being one of the most mind-boggling experiences of my life. When I returned, back in 2005, I wrote up a hundred-page account that I sent to about five friends. They wrote back, “This is amazing. Where are you going to publish it?” And I thought, “Nah, I can’t publish this. It’s too idiosyncratic. Too unbelievable.”

On a whim, shortly after Antoinette died, I pulled the pages out and posted a passage on Facebook. Again, friends said, “This is amazing. Why don’t you publish this?”

I love to write. I needed a project. I edited the pages and began sending the edited manuscripts to publishers.

My Peace Corps experience, and, I think, some of the impetus that prompt many of us to consider Peace Corps life, are evident in this passage.

You are professor of Community and Social Justice at William Paterson College in New Jersey. What are today’s students like? Are they familiar with the Peace Corps, its history, and would joining be something they would want to do after college?

Actually, that’s not correct. I was an adjunct professor in the Anthropology department. In recent years, especially post-COVID, college admissions have cratered, and anyone without tenure, and even some of my colleagues with tenure, were let go. After that, the Anthropology department was renamed. I have been told that if the need arises I’ll be hired back, but given enrollment numbers, I’m not sure that that will occur.

What are today’s students like? Well, I worry a lot about physical fitness. Americans are so much heavier and less active than when I was a kid. I walked three miles to and from work and this shocked my students. This saddens me.

But the human mind has not changed since my youth. People want to know, and people are excited by knowledge, and I loved that aspect of teaching.

Very few of my students were aware of Peace Corps. My students were largely minority and low income, and often first generation. They wanted to move up and out of rough situations. Their focus was on that. Many of course wanted to do good in the world, but their focus was more domestic.

Are you familiar with the books written by other RPCVs over the last 60-plus-years? Is there a novel, memoir, or another non-fiction Peace Corps book that you found particularly insightful?

I think of Paul Theroux. I read his The Great Railway Bazaar under a mosquito net in the Central African Republic. It’s been a long time and I could not produce a careful, well-supported analysis now, but I remember feeling annoyed. I didn’t like Theroux assuming the ability to critique cultures he merely passed through. Other countries do not exist so that rich, white men can be entertained by them, or even to gripe about not having their expectations met by them.

I also think of Broughton Coburn’s book Nepali Ama. Again, it’s been a long time since I read it, but I remember Ama saying, in the morning, go outside, smoke a bidi, and try to defecate, or at least fart. For that sentence to have stayed in my mind all these decades later says something about the book’s power. Coburn brought Nepali Ama, a woman most Americans would never have contact with, to life.

As you are aware, we have had over 60 years of “PCVs” in the world. Based on your own experience, and what you know about the Peace Corps, would you say it has been successful and what, if anything, should the agency do the next generation?

I’m a big believer in objective facts and statistics, and I’m also a big believer in expertise and admitting when one does not have expertise. I have not performed a thorough review of the Peace Corps so I am not qualified to comment on whether or not the Peace Corps at large has been successful.

What should Peace Corps do differently? I have many thoughts about that. FWIW here are three.

A woman I valued highly was raped in Peace Corps by a host country national. Peace Corps administrators handled her case very badly. This is representative of a trend, if news exposés are to be believed. Pieces like this from the agency Peace Corps Commits to Broadening its Approach to Sexual Assault Prevention in New Brief and Roadmap promise a new approach. Hoping for the best.

I was lucky to be friends with a really remarkable PCV, Marie Center, in Nepal. Marie was a brilliant and brave young woman and a recent Dartmouth graduate. She confronted our superiors on the expectation that we would comply with misogynist cultural trends. In some villages in Nepal, menstruating women are required to sleep in a structure called a chaupadi. The New York Times, National Public Radio, and other news outlets have covered chaupadi because it has killed. Nepali women die from exposure, snake bites, and smoke inhalation in these structures. In Africa, I was told, one volunteer pretended to be a Catholic nun because that was the only way she could avoid the endemic disrespect she, as a woman, encountered. I would like to see a serious conversation about the no-man’s-land between our “prime directive” not to interfere with local culture and our desire to create appropriate respect and safety for female volunteers in misogynist cultures.

Related to that, the Peace Corps I knew refused to adopt a clear-eyed approach to the cultural roadblocks to Peace Corps’ stated goals. For example, in CAR, the country hosted epidemic violence so severe that Peace Corps volunteers were some of the few official Americans left in the country. The ambassador and I think even the Marines had fled to avoid CAR’s constant violence. In both CAR and Nepal, girls are so undervalued that they were simply not sent to school. Again, the admins with whom I interacted refused to discuss these matters. “Everything is fine; just keep smiling and do your job. If you bring up any roadblocks, you are an unworthy whiner” was not an adequate response.

Very thoughtful comments—well done

Shame on PC country staff for not handling a raped Volunteer well, there is no excuse for that.

I agree—there is need to examine carefully the dichotomy between “adapting to the local customs”and also creating opportunities and modals for change. I wonder how much this is explored during PC training and in-service conferences?

Marion and John—thanks for publishing this very thoughtful interview with Ms. Goska.