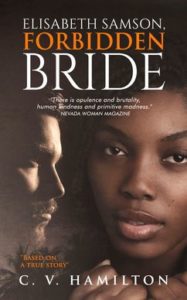

Review — ELISABETH SAMSON FORBIDDEN BRIDE by C.V. Hamilton (Suriname)

Elisabeth Samson, Forbidden Bride

Elisabeth Samson, Forbidden Bride

C.V. Hamilton (Suriname 1999-01)

Swift House Press

June 2020

401 pages

$17.95 (paperback), $3.99 (Kindle)

Reviewed by Stephen Foehr (Ethiopia 1965-67)

•

Elisabeth Samson was a real person, a Free Negress. But members of her family remained in slavery, while others were bought out of enslavement, which is how Samson was born free in the 18th century Dutch colony of Suriname. The situation was ripe for drama and moral dilemma, especially with the addition of a Black/White love affair.

And there is this twist: Elisabeth Samson was a rich plantation owner with hundreds of slaves, importer of luxury European goods, a Dutch colonial wannabe, whose greatest anguish was not being allowed to marry the love of her life, a white man, and that they had not conceived a child.

C.V. Hamilton’s novel Elisabeth Samson, Forbidden Bride is based on Samson’s journals discovered by the author and augmented with extensive historical research. The first-person account, told in diary form, begins in January 1742. Lavish attention is given to the adornments of European culture, but no mention of Samson’s African background and heritage. Spoors of scandal, exile, shame, chicanery, and slave revolt appear in the jagged narrative, but not until nearly a third through the book do these faint traces begin to emerge.

The narrative tone is self-conscious journalese reporting, rather than an easy and informal intimacy expected in a diary. Word usage is occasionally quaint, perhaps to mimic the period language. Samson’s voice is one of indifference, detached reporting without emotional outrage at the cruelties that support her comfortable life. She has more tender feelings for her pet monkey than for the enslaved humans upon whose misery her privilege is built.

Samson is more attentive to the fashion and social niceties of the ruling colonial class (she often sounds like a sycophant of the Dutch authority) than to the reality and exploitation of the slaves. She notes captured runaway slaves hung up to die with an iron hook through their ribs, house slaves castrated and tongue cut out for an offense, a querulous wife of a plantation owner, who drowns a slave baby front of the mother. But those crimes are given a mere nod, not worthy of more than a sentence or two.

Her mercantile attitude towards slaves is an accurate description of the economic system that regulates human beings to the sub-human status of a work object. At one point, she questions the “practicality of complete freedom for slaves” as detrimental for her non-paid workforce.

The novel turns when Samson is accused of treason for slandering the colony’s governor, a twisting of facts, as the ruling Whites consolidated to protect one of their own. She is slandered as a “free whore,” convicted, given slashes, and exiled to the Netherlands. For the first time in the novel, Samson is on the receiving end of caste prejudice. She may be at the top of her class as a wealthy Black plantation owner, but she’d never be allowed into the dominant White colonial caste, a bitter reality that stratifies societies, no matter the written civil rights.

The plot picks up with political intrigue and infighting between the plantation owners and the governor, anti-Semitic attacks within the society, resentment of Samson because she lives “in sin” with a white man that White mothers covet for their marriageable daughters, and conflict with the Maroons, runaway slaves who form villages deep in the jungle and raid the plantations for food, arms, women, and with revenge against their former owners.

Against this backdrop, Samson aggressively pursues her goal to change the 100-year-old law that forbids a White man from marrying a Black woman, although the man can live openly with a Black concubine, a common practice in the colony. She pushed the colony’s governor to take the issue to Court of Policy. Before the law is addressed, Samson’s white lover, with whom she has shared a house for years, dies suddenly at the breakfast table.

Nevertheless, Samson pursues the right to live in legal matrimony with the man of her choice.

“I will have a white husband,” she declares. “I will be equal to the planters’ wives.” Problem is, she didn’t have a husband candidate.

She enlisted a willing man and submitted marriage papers, pointing to a loophole that Dutch law does not specifically stipulate that a White and a Black cannot marry. In the following heated debate, White male members of policy court argued that “It is ludicrous to think that she who is free, by attaching herself through a solemn marriage ceremony, can be like us and their children be our equals. Where is our responsibility as a higher race of whites?”

The problem was kicked to the courts in the motherland. Three years later, the States General of the Dutch Republic ruled that no law existed forbidding marriage between White and Black.

Samson won. But the previous groom-in-waiting had died while the court decided. Undeterred, she made a proposal to a man young enough to her son: Marry me and you will inherit my wealth. The deal was done. The novel makes no mention of the state of the four-year marriage before Samson’s death at the age of fifty-five.

The young widower heavily mortgaged Samson’s properties: Whites became the eventual owners. He never bought a tombstone for her grave, which has never been found.

•

Stephen Foehr, (Ethiopia 1965-67) is the author of numerous nonfiction and fiction books. His latest novel, Warrior Love, Silas Loves Lili Weirdly Lili Loves Silas, was published July 2021. He is working on a new novel. (Stephen Foehr. com)

No comments yet.

Add your comment