Peace Corps faces questions over another Volunteer death (Comoros)

A 24-year-old volunteer died of undiagnosed malaria on the island nation of Comoros. It was one of at least three deaths since 2009 that have been linked to mistakes by Peace Corps doctors.

By Sheryl Gay Stolberg

New York Times

Oct. 2, 2020, 5:01 a.m. ET

WASHINGTON — The Peace Corps, which suspended all operations for the first time in its history as the novel coronavirus raced around the globe, is facing renewed questions about the quality of its medical care — in particular, after the death of a 24-year-old volunteer from undiagnosed malaria — as it prepares to send volunteers back into the field.

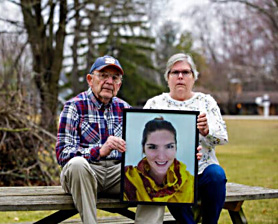

Bernice Heiderman, the daughter of Bill and Julie Heiderman, died of malaria while serving in the Peace Corps. “It’s reckless and it’s terrible,” Julie Heiderman said. Credit–Joshua Lott for The New York Times

The volunteer, Bernice Heiderman, died alone in a hotel room on the island nation of Comoros off Africa’s east coast in January 2018, after sending desperate text messages to her family. Ms. Heiderman, of Inverness, Ill., told them her Peace Corps doctor was not taking seriously her complaints of headache, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dehydration, fatigue, lower abdominal pain, fever, sweats and chills.

An investigation by the Peace Corps inspector general documented a string of problems with Ms. Heiderman’s care. Her Chinese-trained doctor had “limited training in tropical medicine,” the investigation found, and failed to test for malaria, an obvious diagnosis for an American in Africa. And the agency’s medical experts in Washington, with whom he consulted, never asked him to.

The doctor did not conduct routine blood work, which would have revealed that Ms. Heiderman had been infected by the deadliest malaria parasite. The Peace Corps was also using outdated 2006 guidelines for malaria, which did not reflect the current standard of care. Although Ms. Heidermann was not taking the antimalarial drugs the Peace Corps had supplied to her — against its rules — the inspector general faulted the agency’s medical staff in Comoros for not following its “best practice” of tracking whether volunteers were taking their medication.

“Had she received timely treatment,” the inspector general concluded, “she could have made a rapid, full recovery.”

Now the Peace Corps, which evacuated more than 7,000 volunteers from posts in more than 60 countries at the outset of the coronavirus pandemic in March, is accepting applications for those evacuees to return to service. If conditions permit, officials said, some may return to their posts by the end of the year, and new volunteers may begin as early as Jan. 1.

The circumstances surrounding Ms. Heiderman’s death, which have not previously been reported in detail, reflect longstanding problems with the Peace Corps health care system that the agency has repeatedly promised to fix. In 2018, Congress passed legislation demanding improvements. The bill was prompted in part by a New York Times investigation in 2014 that detailed medical missteps that led to the death of Nick Castle, a volunteer in China, in 2013.

Ted Poe, a former Republican congressman of Texas, helped author a bill passed in 2018 demanding improvements to the Peace Corps health care system. Credit– Carolyn Kaster/Associated Press

The bill, which bears Mr. Castle’s name, was signed by President Trump in October 2018, 10 months after Ms. Heiderman died. The legislation was largely written and the Peace Corps was well aware of its provisions at the time of her death, said one of its chief authors, Ted Poe, a former Republican congressman from Texas. “This legislation was to prevent that very scenario from occurring,” he said.

Ms. Heiderman’s parents, who are preparing to sue the agency, said her death was proof that the Peace Corps could not ensure the health of volunteers in ordinary times, let alone during a pandemic.

“It’s reckless and it’s terrible,” Julie Heiderman, Bernice’s mother, said in a recent interview, referring to the agency’s plan to resume operations. “From what we know and what happened with Bernice, it’s dangerous.”

Beyond the Peace Corps’ medical mistakes, the Heidermans — Mrs. Heiderman, her husband, Bill, and their other daughter, Grace — said they were appalled at what they called the Peace Corps’ callousness. After Bernice’s death on Jan. 9, the Heidermans said, the agency, citing a need for “efficiency,” delayed sending the body to Germany for an autopsy until it had other reasons for a flight. The timeline for her return home kept shifting, but based on the Peace Corps’ assurances, they scheduled a church funeral for Jan. 20.

The body had not arrived by then and the Heidermans, exhausted, went ahead with the funeral anyway. Bernice’s remains finally came home four days later.

Peace Corps officials declined to be interviewed. In an unsigned email sent by the agency’s press office, the agency said it “continues to grieve the tragic loss of volunteer Bernice Heiderman” and “initiated several steps to further strengthen health care for volunteers” after she died. The agency said the doctor who misdiagnosed Ms. Heiderman, Dr. Nizar Ahamada Said, no longer works for the Peace Corps.

Founded in 1961 by President John F. Kennedy to spread American good will around the world, the Peace Corps is a quasi-government agency. Its volunteers are not considered federal employees, which has made it difficult for them to receive help from the government if they become victims of crime or return home with lasting illnesses or injuries.

“They’re the ones that served. We ought to take care of them,” Mr. Poe said.

Deaths in the Peace Corps are relatively rare, and often occur as a result of an accident or injuries. Including Ms. Heiderman, nine volunteers have died in the past three years.

But while serving in the Peace Corps is inherently risky, deaths from malaria are “not acceptable,” said Dr. Michele Barry, the director of the Center for Innovation in Global Health at Stanford University, who reviewed the inspector general’s report at the request of The Times.

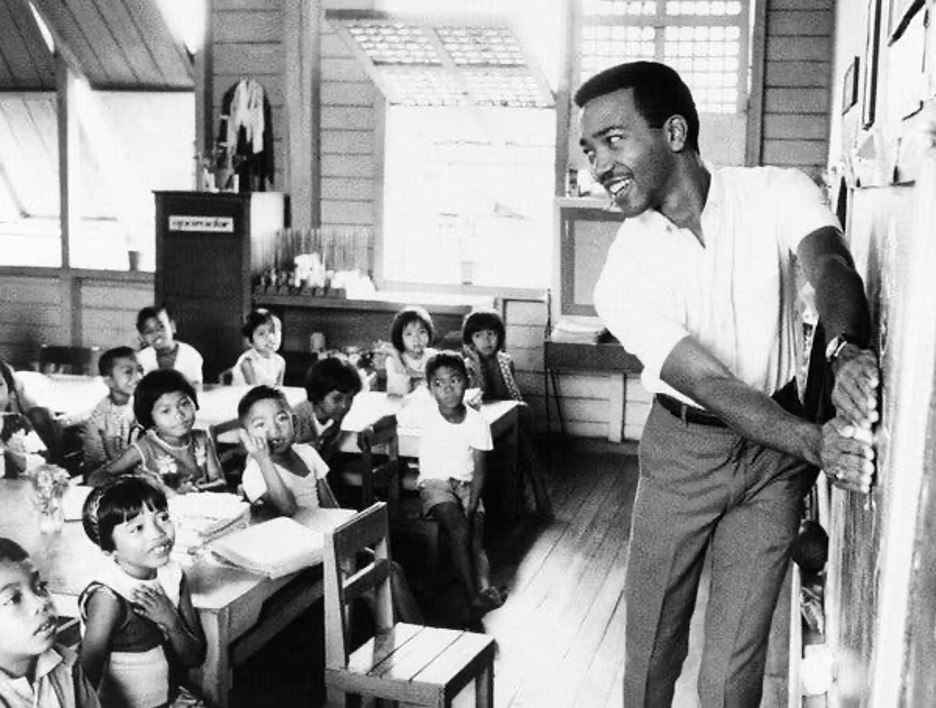

Louis Jenkins, a Peace Corps volunteer, teaching English to students in the Philippines in 1970. Credit—Associated Press

“You can take risk from accidents, motor vehicle accidents, other kinds of low-income country settings — poor water and safety — but you should not be taking a death from malaria,” she said. “That’s an easily preventable and an easily treatable disease if caught early.”

The Peace Corps employs doctors and other health care providers at each of its posts around the world, who are overseen by experts in Washington. The agency uses its own medical records system that allows officials at headquarters to consult with doctors in the field.

It promises its volunteers “necessary and appropriate health care” provided by “highly qualified professionals who are all carefully evaluated and credentialed by the Peace Corps.” If quality care is not readily accessible, the agency “will transport the volunteer to an appropriate facility in a nearby country or to the U.S.,” its website says.

The reality, according to former volunteers, their families and congressional investigators, is far different. While many who serve say the experience provides immeasurable rewards, those who get sick or injured often feel lost in a maze of bureaucracy. That has prompted repeated calls for change.

In 2011, after female Peace Corps volunteers who had been sexually assaulted while serving complained about their treatment, Congress passed a bill, signed into law by President Barack Obama, requiring more support for volunteers who become victims of crimes. But there has been scant oversight of Peace Corps health care, Mr. Poe said

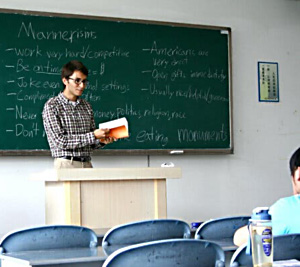

Nick Castle, a Peace Corps volunteer, teaching at a model school in Chengdu, China. A bill Congress passed in 2018 was prompted in part by the disclosure of the medical missteps that led to Mr. Castle’s death in 2013. Credit—Alice McCutcheon

The death of Mr. Castle — and the advocacy of his parents — changed that. He sustained severe complications from a gastrointestinal illness, but his Peace Corps doctor did not send him to the hospital until it was too late. The Peace Corps inspector general, which investigated the death after publication of The Times article, concluded he died after “cascading failures and delays in treatment.”

The intent of the bill was to codify good health care practices and give them the force of law, Mr. Poe said. It requires Peace Corps volunteers to have access to embassy doctors — the same doctors who treat State Department officials — if they need them. And it requires them to finally put into effect 10-year-old recommendations that grew out of serious medical lapses that led to the death of So-Youn Kim, a 23-year-old Stanford University graduate who served in Morocco in 2009.

In the case of Ms. Heiderman, Peace Corps faulted her in its formal response to the inspector general for not following the agency’s requirements to take antimalarial drugs or “fully disclose” that she had not done so.

“That is not a defense,” Dr. Barry said. “It is up to them to insure that Peace Corps volunteers are taking their meds and at the very least, when a patient comes in, that should be your first question.”

An investigation by the Peace Corps inspector general documented a string of problems with Ms. Heiderman’s care. Credit–Joshua Lott for The New York Times

A 2016 graduate of the University of Illinois at Chicago who aspired to be a museum educator, Ms. Heiderman joined the Peace Corps and was assigned to Comoros, in the Indian Ocean between Madagascar and Mozambique. There, she taught English to junior high school students in the capital city of Moroni, and drew on her experience working at Chicago’s Field Museum to start a Junior Exploration Club for her students.

On Dec. 31, 2017, Ms. Heiderman and some other friends went to a hotel in Moroni to celebrate the coming new year. But that evening, she was not feeling well, and complained of nausea, said Luke Garfield, a fellow volunteer. The next day, she texted her mother to say that she “could not stop shaking from the chills,” and felt like she was “in a fog,” according to a narrative prepared by the family’s lawyer.

The Peace Corps had one doctor in Comoros, Dr. Said, who had been hired by the agency several years earlier. He had an assistant who holds a nursing degree but had also worked as a pharmaceutical and dental technician.

According to the inspector general’s report, Dr. Said’s notes from Jan. 2 show that Ms. Heiderman’s pain level “was noted as 8 out of 10.” The doctor “suspected a headache disorder,” and gave her acetominophen for her headache, as well as medicine for nausea, an antacid and a decongestant, and “told her to drink more water and rest.”

The next time she saw Dr. Said, on Jan. 4, her symptoms had only grown worse. The doctor put her on a “medical hold,” and sent her to stay in a hotel, where he could remain overnight in a nearby room. He gave her intravenous fluids “to control her nausea and vomiting.”

The records reflect that Ms. Heiderman did not have the kind of high fever that is typical of malaria, but the Peace Corps requires its health professionals to “always consider a diagnosis of malaria” in any volunteer, especially one serving in an area where the disease is prevalent, such as Comoros.

On Jan. 8, with Ms. Heiderman suffering from what Dr. Said believed was

”dehydration due to severe vomiting,” the doctor appealed to Washington for help and Dr. Alison Colantino, the director of the Office of Medical Services for the Peace Corps, became involved, the inspector general reported. It had been a full week since Ms. Heiderman fell ill. Dr. Colantino told Dr. Said to do lab work the next morning, and to call a regional medical officer in South Africa if Ms. Heiderman’s fever spiked, and to do blood work the next morning.

That day, Ms. Heiderman’s mother and sister sent a flurry of frantic texts asking her to check in. They never received a reply. At 5:33 a.m. in Comoros on Jan. 9, Dr. Colantino raised the possibility of a medical evacuation. Less than 30 minutes later, Ms. Heiderman was dead.

Sheryl Gay Stolberg is a Washington Correspondent covering health policy. In more than two decades at The Times, she has also covered the White House, Congress and national politics. Previously, at The Los Angeles Times, she shared in two Pulitzer Prizes won by that newspaper’s Metro staff. @SherylNYT

Having served in Sierra Leone in 1990-91, I experience our medical officer, an American, did not know what the little red spots on my hands and arms were do to, he replied, ” why are you showing me this?”. Fortunately one of our host country nationals was with him and offered that they were bedbug bites, which was correct. My mattress was treated in the sun no further problem existed. I found his reply to me inappropriate for a licensed medical physician, particularly from the US.

When hopefully Peace Corps re-opens (top priority must be given to our medical offices assigned to especially rural districts.)

Sincerely,

Barbara T, Gershberg, RPCV

Morocco: 1990 -91, Sierra Leone: 1992-1993 Yemen: 1993-1994, Morocco: 1995-98.

Due to evacuations due to various political reasons arising in those countries at that time.