In That Time of Their Lives — Jeremiah Norris (Colombia)

RPCVs in the news —

by Jeremiah Norris (Colombia 1963-65)

. . .

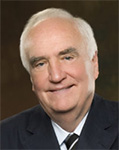

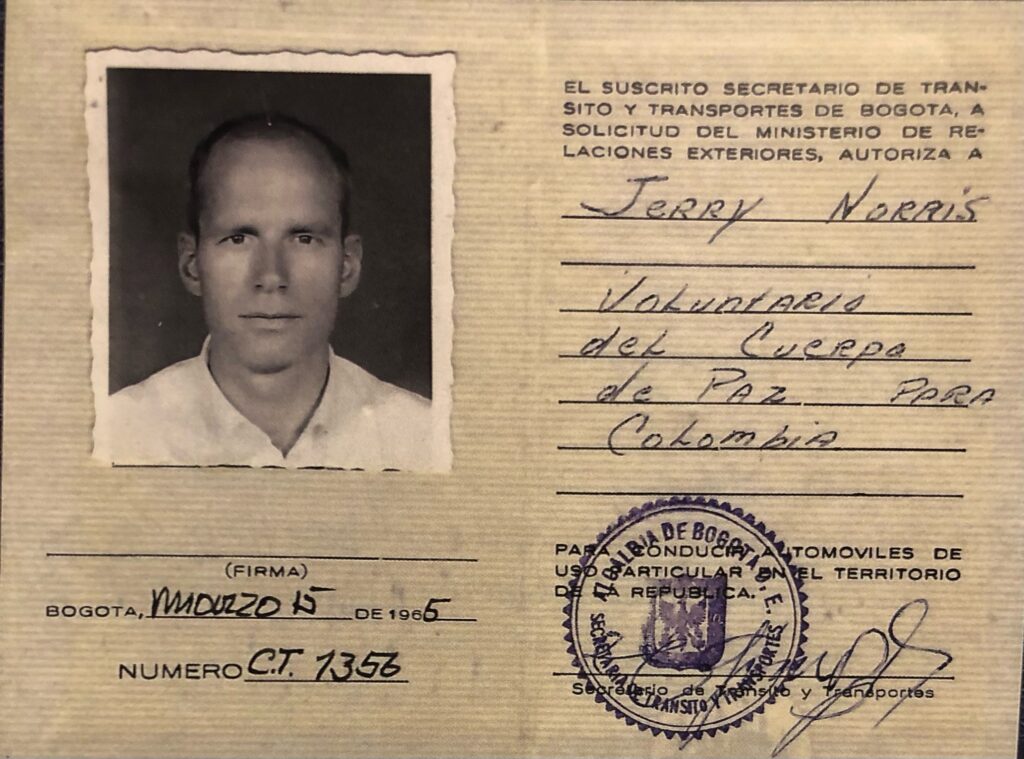

Jerry Norris (Colombia 1963-65)

The Peace Corps came into existence through an Executive Order from the President of the U. S. in March 1961. It had three complimentary goals, the 3rd of which stated: “To help promote a better understanding of other peoples on the part of Americans”. This Goal, often summarized as “bringing it back home”, has always been something of an afterthought—because it lacks documentation, though it is worth documenting …it represents a Return on Investment (ROI) that is unmatched by any other Congressional appropriation. In the decades that followed, it passed through two events of global consequence, either one which could have resulted in its organizational demise: the Viet Nam War and the Covid-19 epidemic.

In the past several years, one would have to have been an expert in forensic sciences to find any article in the press or social media on the Peace Corps. Then, in March 2020, a virus resurrected it to public awareness when all of its 7,000 Volunteers were recalled from their overseas posts out of an abundance of caution for their health. If Volunteers in active service aren’t perceived as visible representation of the Peace Corps’ raison d’etre, then perhaps it can be found in the dividends that Returned Volunteers continue to invest in our society as responsible citizens of the world. They are emblematic of the Peace Corps’ 3rd Goal.

Since its founding, some 245,000 Volunteers have served around the world, with dozens of them serving as U. S. Ambassadors to 80 different countries. Yet, the sole notice that the Agency was still functional during the Covid-19 crisis was via an almost daily flow of publications by the social media platform ‘peace corpsworldwide’. It gave voice to so many returned Volunteers, here they found a home through which they could publish their short stories, their remembrances of time as Volunteers and its significance to their professional lives; a review of their books; to share all this with a receptive community that had once lived an impossible dream; and to recapture timeless memories of the ‘way we were’.

Many of us came from a generation deeply conflicted by the moral dilemma of our country’s war in Viet Nam. We could be Volunteers and enrolled into an ‘army of peace’, as Theodore Sorenson described the Peace Corps to newly elected President John F. Kennedy in 1961. Still, others of our generation, who were less advantaged and with limited choices, had to serve in distant armies on far shores and jungles, in places they never could have found or pronounced correctly in their 6th grade, geography books. They were treated with such distain by their fellow countrymen when returning home that if an epitaph for that generation had been written then –and even now, a simple declarative sentence would suffice: they are lost to us. We, though, were privileged to find in our Volunteer service a spiritual home for our aspirations, even if unable to fully fathom the currency that value was to represent in our future lives.

What career trajectories did they take to honor that Goal? And how collectively did they make the case for its annual fiscal renewal from the Congress. The vast publications of WorldWide were proof positive that the Peace Corps’ 3rd Goal gave credence to the entire Agency itself and were more than sufficient a reason for its continued operational support. Perhaps some examples will state the case more vividly.

Hal Hardin

Hal Hardin (Colombia 1963-65)

Let’s take the case of Hal Hardin, a RPCV who served in Colombia 1963-65. A staunch Democrat and a benefactor of the Democratic Governor of Tennessee, he was appointed by President Jimmy Carter to be the Attorney General for the Middle District of Tennessee. In 1978, Hal was provided with information by the FBI that the Governor had recently commuted the terms or pardoned fifty-two criminals in the middle of the night in a cash for release transaction. Hel was now face to face with that unforgiving task master … fidelity to an oath of public office. The Governor elect was a Republican. In the space of 24 hours, all of the Democratic leadership had to set loyalties aside and decide, with the one Republican, how to stop the Governor from issuing more pardons. On that day, the FBI informed Hal that more commutations for cash were being prepared. Armed with legal information from the Attorney General that the State’s Constitution made a critical distinction, permitting a governor-elect to be sworn into office as early as 12:01 am on January 18, with the official inauguration to follow on the 20th. Hal then phoned the Governor-elect on January 17, saying “I am calling you as a Tennessean, not as the Attorney General. The Governor is about to release some inmates who we believe have bought their way out of prison. Will you take the oath of office as soon as you can to stop him?”

Hal’s call initiated secret meetings on the afternoon of January 17. Each of the Democratic officials knew what had to be done, yet they were reluctant participants in taking an action that could be seen as a coup more befitting a banana republic. The Governor-elect would only agree to be sworn in early if they all concurred that it was necessary—and that it was their idea, not his. The only constant on setting their moral compass on what had to be done—and quickly, was Attorney General Hal Hardin. Under State law, pardons are irrevocable, no matter the circumstance of their issuance.

Finally, an agreement was reached with the Attorney General, Speaker of the House, the Lt. Governor, and the Governor-elect. With the exception of the Governor-elect, all were Democrats. They visited the Chief Justice at his home, requesting that he swear in the Governor-elect early. Taking their cue from Hal that they were Tennesseans first, this became the basis for a bond of mutual trust. The Republican elect-Governor, took the Oath of Office at 5:55 on January 17. The pardons were halted. He took the Oath a second time on January 20 at a formal inauguration.

Hal Hardin was the living embodiment of a Profile in Courage, a person who used his time with a public trust to demonstrate that primacy to the rule of law takes precedence over any political loyalty. He was a force multiplier to JFK’s clarion call to “Ask not” In a fitting tribute to a man guided by a moral courage that never wavered, he was named president—elect of an exclusive organization, the National Association of Former United States Attorney Generals.

Dona Shalala

Donna Shalala (Iran 1962-64 )

Or, how about Dona Shalala who was among the first to join the Peace Corps in 1962, working in Iran to build an agricultural college. She then went on to earn a Ph. D. from the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public and Public Affairs at Syracuse University. In 1970, she began her academic career as a political science professor at Baruch College. After, she went on to became the tenth president of Hunter College, serving in that capacity until 1988. She next served as Chancellor of the University of Wisconsin until 1993, the first woman to lead a Big Ten Conference School and only the second women in the U. S. to head a major University.

Following a year serving as Chair of the Children’s Defense Fund from 1992-93, she was nominated by then-president Clinton for the position of Secretary of Health and Human Services, serving in that role for eight years and becoming the nation’s longest serving HHS Secretary. After the end of the Clinton Administration in 2001, Dona went on to become the President of the University of Miami, a post she held until 2014.

Ever resourceful, Dona went on to become CEO of the Clinton Foundation from 2015-17. In March 2018, she declared her candidacy in the Democratic Primary for Florida’s 27th Congressional District. In the primary, she won the seat by 31.9% of the vote. She went on to the general election, winning the Congressional seat at the age of 77, making her the second-oldest freshman Representative in history.

Over a life time of public service, Dona was elected to the Council on Foreign Relations, the National Academy of Education, the National Academy of Public Administration, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Philosophic Society, the National Academy of Social Insurance, and the National Academy of Medicine. In 2008, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom and in 2010, she received the Nelson Mandela Award for Health and Human Rights. To round out her incredible service to our nation, she was announced as one of the members of the Inaugural Class of the Government Hall of Fame—a tribute that marked her incredible passage through the halls of higher education and senior levels of government service.

Reed Hastings

(Swaziland 1983-85)

And, then there is Reed Hastings who in his gap year before college sold vacuum cleaners door to door before serving as a Peace Corps Volunteer 1983-85, teaching math in a high school of 800 in rural Swaziland. Afterwards, he went on to Sanford University, earning a Master’s in Computer Science. In 1997, Reed and one of his colleagues co-founded Netflix, offering flat rate movie rental-by-mail to customers in the U. S. by combining two emerging technologies: DVDs which were easy to send as mail than VHS-cassettes, and a website to order them from instead of a paper catalogue.

Reed expanded Netflix through movie studio partnerships and aggressive marketing campaigns, emphasizing Netflix’s catalog of films, documentaries, and other movies not easily accessible through other services. In February 2007, Netflix shipped its billionth DVD, with Reed himself becoming a multi-billionaire. He credits part of his entrepreneurial spirit with his time in Peace Corps, remarking that “once you have hitch-hiked across Africa with ten bucks in your pocket, starting a business doesn’t seem too intimidating”.

Since 2012, Reed has been a Giving Pledge Member, a program to encourage extremely wealthy people to contribute a majority of their wealth to philanthropic causes. He has contributed $30 million to the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations; $120 million to be equally split between the United Negro College Fund, Morehouse College, and Spelman College; $100 million to the United Negro College Fund and the Hispanic Foundation of Silicon Valley for college scholarships; and $1 million to the Beacon Educational Network to open up new Charter Schools. His overall philanthropic donations now exceed over $252 million, constituting about 55% of the Peace Corps annual budget in that year.

Mildred Taylor

Milly Taylor (Ethiopia 1965–67)

Well, how about Mildred Taylor, who served as a Volunteer in Ethiopia from 1965 to 1967. After returning to the U. S., she earned an MA Degree in Journalism at the University of Colorado where she was instrumental in creating a Black Studies Program as a member of the Black Alliance. Mildred is best known for exploring powerful themes of family and racism faced by African Americans in the Deep South in works that are accessible to young readers. She was awarded the 1977 Newbery Medal for Roll of Thunder, Hear Me Cry, and the inaugural NSK Neustadt Prize for Children’s literature in 2002. In 2021, she won the Children’s Literature Legacy Award.

Overall, Mildred’s books chronicle the lives of several generations of her family, from the time of slavery to the Jim Crow era. Her most recognizable work is Roll of Thunder which has been integrated into the language arts curriculum of many classrooms across the U. S.

In comments made by Mildred, she described the source materials for her books. In visits to her parents and grandparents house amid the South of racism and bigotry. there was also the South of family and community and history that filled her with pride. Here, “the adults would begin to talk of about the past and I would begin to visualize all the people who once lived in that house, all the family that once had known the land, and I felt as if I knew them, too. I met them through all the stories told with such gusto and acting skills that people long since dead lived again through the voices and movements of the storytellers”.

Other book awards included the Coretta Scott King award in 1990 for The Road to Memphis, and Let the Circle Be Broken being awarded as Outstanding Book of the Year Citation by the New York Times in 1981; the Christopher Award in 1988 for the Gold Cadillac; and for Song of the Trees, voted as the Outstanding Book of the Year Citation by the New York Times in 1975. Mildred’s long standing professional skills in chronicling her family’s oral history of racism faced by African Americans in the Deep South into well received novels, most especially for children.

Chris Dodd

Chris Dodd served as a Volunteer in the Dominican Republic, 1968-71, after graduating from Providence College. Thereafter, he was elected to the first of his three terms as a Representative in 1974. He was elected to the U. S. Senate in 1980. He was reelected in 1986, 1992, 1998, and 2004.

Chris’s time in the U. S. Congress was marked by an interest in child welfare, fiscal reform, and education. While serving in Congress, Chris wrote our nation’s first childcare legislation—the Family and Medical Act, which he had spent nearly a decade in working to enact. He also founded the Children’s Caucus in Congress, and drove legislation to fully fund Head Start, childcare, and preschool programs to reduce childhood hunger and help lift families out of poverty and provide services for premature infants and children with autism.

Chris’s father, Thomas, served as a jurist in the Nuremberg Trials after WW II. His papers from that trial were memorialized in Chris’s book Letters from Nuremberg: My Father’s Narrative of a Quest for Justice. For Chris, the lessons of Nuremberg helped guide a noteworthy career of public service, punctuated by a legacy of human rights advocacy and action.

Facing a difficult reelection campaign in 2010, he announced that he would not seek a 6th term in the U. S. He later served as Chairman of the Motion Picture Association of America.

Kathleen Stephens

Kathleen Stephens (South Korea 1975–1977)

Kathleen Stephens was an RPVV who served in South Korea, 1975-77. Early on in her remarkable career, Kathleen began running the table on foreign policy appointments, by serving in two missions in the People’s Republic in China, 1980-82, in Trinidad and Tobago, 1978-80. Her tour in South Korea included roles as Internal Political Unit Chief at the U. S. Embassy in Seoul, 1984-87; Principal Officer at the U. S. Consulate in Busan, 1987-89; afterwards, Kathleen worked as Political Officer at the U. S. Missions in Belgrade and Zagreb, 1991-92, senior Desk Officer for the United Kingdom in the Bureau of European Affairs, 1992-94; Director for European Affairs at the U. S. National Security Council, 1994-95; Principal Officer at the U. S. Consulate as the U. S. as the U. S. Consular General in Belfast, Northern Ireland, 1995-1998; Deputy Chief of Mission at the U. S. Embassy in Lisbon, Portugal, 1998-2001, and—finally as Director of the Office of Ecology and Terrestrial Conservation at the U. S. Department of State, 2001-2003.

All of these appointments were earned through hard work after Kathleen joined the Foreign Service in 1978—all the way up to serving as Ambassador to South Korea under two different U.S. Presidents, and charge d’ affairs to India. She was well equipped to meet these professional challenges, speaking fluent Korean, Serbo-Croation, and Chinese.

Of her experience as a Volunteer, Kathleen wrote: “this is where I learned the qualities I needed to be a diplomat; I learned how to endure hardships and convince others.”

Drew Day

Drew Day (Honduras 1967–69)

Drew Day, a Returned Volunteer who served in Honduras, 1967-69. Returning to the U. S., Drew became the first assistant counsel at the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund in New York city. He worked there for eight years, litigating a range of civil rights cases. He was admitted to practice law before the U. S. Supreme Court, and in the states of Illinois and New York.

In 1977, then-President Jimmy Carter nominated Drew to serve as the Assistant General for Civil Rights in the Department of Justice. His tenure was marked by an aggressive enforcement of the Nation’s Civil Rights Laws.

In 1993, then-President William Clinton nominated Drew to serve as Solicitor General in the Department of Justice. In that position, he was responsible for representing the positions and interests of the United States in arguments before the Supreme Court. After leaving the Clinton Administration, Drew returned to Yale Law School and private practice. He was involved in national and international efforts to resolve social and economic issues, including poverty alleviation, the environment, and juvenile justice.

. . .

Bio for Jeremiah Norris (Colombia 1963-65)

Jeremiah Norris spent his formative years in St. Mary’s, an orphanage north of Des Plaines, Illinois. After high school, he served in North Korea as a tank commander. Returning home in 1955, he enrolled at the University of Illinois’s Institute of Aviation, earning a Commercial Pilot’s license, and then returned to the University to complete his BS degree in 1961.

In 1963 he joined the Peace Corps and went to Colombia. Finishing his tour, he joined the Peace Corps staff in D.C. and in 1970 he was the first Director of Administration for the International Peace Academy, then located in Vienna, Austria.

In 1974, he began a career in international health, starting as the Program Officer under a USAID contract to reform health care in South Korea. Over the following decades, Jerry was a senior staff member with Family Health Care; the WebMD Foundation; Management Sciences for Health; the Battelle Memorial Institute; Project HOPE; Harvard Medical School; the Atomic Energy Agency’s Program of Action on Cancer Therapy; and the U. S. Department of State.

In the Administration of G. H. Bush he managed the Government’s response to direct social investments in the former states of the USSR and Eastern Europe.

Jerry has also been a Guest Lecturer at MIT-Harvard Joint Graduate Program in Global Health; at George Washington University’s program in public health; the National Defense University; and the Woodrow Wilson Center. He published widely in Letters to the Editor. guest columns and Op Eds in the British Medical Journal; Lancet; Financial Times; South China Morning Post; Business Day; International Hospital Federation; European Enterprise; and the journals Science Direct and American Outlook.

In 2001, he became a Senior Fellow at the Hudson Institute’s Center for Global Prosperity and has presented lecturers on the emergence of chronic diseases in the developing world at regional conferences and was a member of the Department of Commerce’s Task Force on Counterfeit and Substandard drugs.

To be continued….

Wow! What a tour de force. Thank you Jerry.

Perhaps we should invite all RPCVs to publish their bios and publish it in a book called Profiles in Accomplishment or something simolar

Best

G.

Gary, great thanks for your comment. Good idea about getting other RPCVs to write their Goal 3 stories. Our attempt is minor at the moment but maybe it will encourage others to get into it.

Warmly,

Jerry

Jerry, you’re the best at profiles, and these are complemented by your own enviable background of lifelong public service.

Steve,

I greatly appreciated your comment–and support.

Warmly,

Jerry

Jerry, what a tremendous collection of RPCV bios. They beautifully illustrate Peace Corps’ Third Goal and make for fascinating reading whatever the purpose. Thanks for your great work.

Jack Swenson, P.C.Colombia ’63-’65

Jerry:

A wonderful essay and thoroughly informative bios, not ;least about yourself. I confess I did not know the extent and depth of your post PC professional career.. Congrats on the publication of this excellent piece.

And you look like an Ambassador to The Crown.

Saludos, Jerry

It’s delightful to find your post and succinct observations about the Peace Corps and what it has brought to the world over the last sixty plus years. Not to mention your personal achievements, Jerry.

We have a unique connection, Jerry. In ’64-’65 I was working with the Peace Corps literacy program in Bogota. Our paths often crossed in the Peace Corps office. Your mature and sage advice was much appreciated by a guy who often needed that. There have been many adventures in this life, but none as rich as those Peace Corps years.

For the last years, living in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, I’ve had contact with Peace Corps Volunteers in Queretaro State next door. It’s gratifying to see that the dream still lives on.

Terry Singleton Colombia ’64-’66