“Ernesto” in Pamplona by Ron Arias (Peru)

NOTE: Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s HEMINGWAY will premiere April 5, 2021 on PBS. The three-part, six-hour film series explores the life and work of Ernest Hemingway. Voice actors include Jeff Daniels as Hemingway and Meryl Streep, Keri Russell, Mary Louise Parker and Patricia Clarkson as Hemingway’s Four Wives.

The Peace Corps has its own Hemingway Connection. Read artist and writer Ron Arias’s own story “Ernesto.”

Ernesto

By Ron Arias (Peru 1963-64)

The English couple who picked me up outside Zaragoza said they were going to Pamplona to find Ernest Hemingway.“He brought us to Spain,” the woman said. “We’re here because of him.”

“Bullfights she means,” the man said. “Hemingway’s the master on bullfights. We heard he was going to be in Pamplona for the fiesta, so we came on over.”

“From Barcelona,”the woman explained. “We want to thank him for — ”

“The corridas,” the man cut in. “They make us feel alive.”

“Or just awful,” she added, “if the thing’s not done right.”

“Meaning the kill,” he said. “It’s all in the thrust . . . .”

I listened to the two of them go on about bullfighting. They sounded cheerful and didn’t seem to mind interrupting each other, laughing even when talking about dying bulls and gored matadors. I was just happy they picked me up. I could still have been out on the highway trying to hitch a ride if they hadn’t stopped.

The back seat of their Citroën sedan was comfortable and warm and I was starting to doze off. They didn’t seem to notice. They weren’t even talking to me, so I didn’t have to speak. I just closed my eyes and pretended to listen, fading into easy sleep.

“Hello! We’re here!” It was the man’s voice. “Pamplona!”

I opened my eyes and looked out the window. I saw that we were stopped at a gas station, which I figured was my cue to leave.

I thanked them for the ride and opened the door, pulling my backpack and rolled-up sleeping bag after me. We traded goodbyes and I wished them luck in finding Hemingway. They laughed and I moved out to the street in search of a place to stay.

It was late afternoon and I checked my guidebook. It listed a cheap shelter run by the Catholic Church. All through France and into Spain I stayed in campgrounds, hostels, even under trees. I’d never spent the night in a shelter for the poor. But I was down to living on a few dollars a day, so the shelter, which would also feed me for free, seemed a good choice.

By the time I got there, it was dark. The nun who opened the little peep door told me I was lucky — they still had some empty cots. She let me in and I followed her to a stairwell that led down to the basement dormitory. I smelled garlic and then two unshaven men walked by us and started down the stairs.

One of them said, “Good evening, sister,” and she replied, “Gentlemen, may God bless you.” When I heard this in Spanish, it sounded so formal — Caballeros, que dios os bendiga — and the grungy pair hardly looked like gentlemen. But I was thinking that she was a “sister of mercy,” and the mission of the order is to treat everyone, especially derelicts, with respect and compassion.

The nun, who was small and dressed in a brown habit, informed me that if I followed those men to the dormitory I could use the empty cot on the left-hand side. She also told me that dinner was still being served in the cafeteria, that drinking alcohol was forbidden, and that curfew was at nine, no exceptions. “Bad luck if you’re not inside by then,” she said in an incongruously sweet voice. “Doors are locked until morning.”

She left and I carried my stuff downstairs. The dormitory was a long room with about two dozen wood-frame cots on each side. I found my spot and sat down on the canvas next to a folded blanket, a clump of sheets and a lumpy pillow.

Looking around, I saw men sitting or stretched out on their cots. Some had gray beards and not all looked poor.

I needed to piss but I was wondering whether or not to leave my backpack behind to go use the restroom.

“I’ll watch your things,” said a deep voice behind me. It was the bald man two cots away gesturing with a hand toward the restroom. “Go. They’re safe with me.”

When I returned, he said I should go eat and not to worry about my things.

Later, after filling myself on potato and cabbage stew, I met another neighbor, Francisco, who was in Pamplona to run with the bulls in the morning. He told me he was a bookkeeper in Madrid and the run was the one wild thing he did every year. No wife, no kids — “just me and fate,” he said.

Our talk trailed off and Francisco fell asleep. The dimly lit room slowly filled with a chorus of wheezy breaths, snoring, and grumbles about not being able to smoke or drink. “God gave us wine for a reason,” someone muttered. As I faded, I heard drunken voices from the street.

I woke up about eight in the morning. Many of the men, including Francisco, had already left to do the run. But my bald neighbor was still here. He was coming from the restroom holding a toothbrush. When we got to talking again I found out he was not here for the bulls. “I’m here to find Ernesto,” he said.

“Ernesto?”

“The writer, Ernesto Hemingway.”

“Ah, of course.”

“Have you read his books?”

“Only two,” I answered. We were speaking Spanish and I was translating the titles in my mind when he waved a paperback copy of Siempre sale el sol [The Sun Also Rises] and said yesterday’s newspaper had a story about Ernesto visiting Pamplona. He wanted me to help him find the author. I shook my head and explained that I wasn’t that big a fan. “But I like movie,” I said. “Oh, and I also read El viejo y el mar [The Old Man and the Sea].”

“Well, then,” he said, chuckling, “I’m going. You go back to sleep.” After he left I laid back and closed my eyes. Tyrone Power was embracing a voluptuous Ava Gardner. I started thinking maybe I was missing something. So I washed up, left my pack with the sisters, promising to stay another night, and went out on the street.

It was never my intention to go hunting for Hemingway, but now that I entered the plaza where a lot of the fiesta crowd was, I thought I might as well. What the hell. I couldn’t afford a ticket for the afternoon bullfight and I had nothing better to do.

I walked over to where tourists and locals were gathering on the shady side of the square. Many of the men were wearing white shirts, trousers, red neckerchiefs and red berets. It was only about eleven but it looked as if the party started hours ago. People were singing and drinking wine from leather botas, holding them up and trying to aim tiny streams into their mouths. I heard someone say it was a great run — only a few guys were sent to the hospital and there were no deaths. If I could get up early enough maybe I’d see the run tomorrow morning.

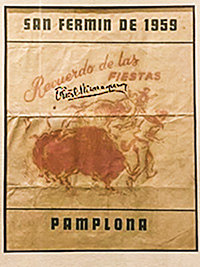

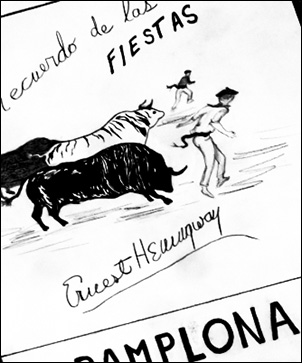

An old man wearing a black beret handed me a flier announcing the lineup of matadores for the afternoon bullfight. At the top of the flier were the words SAN FERMIN DE 1959. Below that, in the center, was a sketch of two bulls chasing two men. At the bottom were the words, Recuerdo de las FIESTAS.

An old man wearing a black beret handed me a flier announcing the lineup of matadores for the afternoon bullfight. At the top of the flier were the words SAN FERMIN DE 1959. Below that, in the center, was a sketch of two bulls chasing two men. At the bottom were the words, Recuerdo de las FIESTAS.

I folded the flier, put it in my shirt pocket and moved on. Now and then I overheard people talking about Hemingway, that they’d seen him the day before, that they’d be the first to spot him today. But the hunters couldn’t be that serious because after only about twenty minutes of wandering around, I saw a broad figure with a short white beard seated at one end of a long, wooden picnic table set out in front of a restaurant on the sunny side of the plaza. A billed cap shaded his face and he was seated with two men and a woman. From what I could see, he perfectly fitted the image I had of him.

I approached, flier in hand, until I stood by the table in front of him. “Excuse me, Mr. Hemingway, could I get your autograph?”

He looked at me through tinted glasses. The others next to him kept talking, but he was just staring, maybe annoyed that I intruded, or maybe he was sizing me up. I didn’t know. Did I have the wrong man?

Finally, he smiled. “Want some wine?”

“Sure.”

Then he excused himself from his friends, stood and moved to the other end of the table. We sat opposite each other. He had brought along a bottle and his glass, and now a waiter set down a glass for me.

Hemingway poured, we drank, and then he signed my flier. I looked around, expecting others to ask him for an autograph, but no one approached. The crowd was still buzzing over this morning’s bull run and now the wine had taken over.

“What’s your name?” he asked.

I told him and then he wanted to know where I was from. Los Angeles, I said, explaining that my dad was in the Army, stationed in Germany, and that was where I lived. Hemingway asked what I want to be and I told him I wanted to be a writer, that I wrote for my school paper and literary magazine.

He kept asking questions and I kept answering. Who were my parents? I said my grandparents came from Mexico and my parents were from El Paso and Nogales. He wanted to know if I spoke Spanish. He asked about the hitchhiking and if I had a girlfriend, which I didn’t. And then, “What do you read . . . what do you write . . . what do you believe?”

“You mean . . . like God?” I said.

He nodded.

“I don’t know.”

“Good.”

It seemed he had a list. “What do you like?”

I told him I liked watching the streetwalkers in Paris outside the Pigalle youth hostel where I stayed. He smiled and then asked about my hitchhiking.

On the road south of Lyon, I ran from a one-arm, one-eyed man who chased me out of his shack, I said. And outside Zaragoza, an English couple stopped to rescue me from the highway heat and dust.

Hemingway wanted to know where I was staying in Pamplona. I described the shelter, the nun, the men on the cots, my bald neighbor, everything, right up to the moment I wandered over to the plaza and spotted him.

He paused, squared me up again, then nodded in a sort of signal that it was my turn to be curious and ask questions. So I asked him what he thought of Pamplona today compared to what it was in the 1920s when he wrote the novel.

“Hell of a difference,” he said. “Not so many damned tourists.” He put his elbows on the table and leaned forward. He remembered the Fiesta de San Fermín as a country fair with truckloads of people from the countryside coming in for the big party. “What’s happening is sad,” he said. “I blame myself. I had something to do with it.”

For a moment, his gaze flicked away from me. Then he smiled and said, “But the music is still lively and the wine tastes as swell as ever.”

I finished my glass of red, wanting to stay longer but I didn’t know what to say, what to ask. Only stupid questions on my mind, or none at all. I wished I’d known more about him, about his writing, about fishing and hunting, about his early newspaper reporting days, about life, about everything. I felt tiny, inadequate, awkward. I’m taking up your time. You’re looking at me, waiting for me to speak and I can’t.

Finally, I thanked him for the wine and rose up off the bench. He remained seated but we shook hands. As I stepped back and started to move away, he shouted my way and I waved to him.

Two years later, he would shoot himself at his home in Idaho. I would read about his mental problems, his paranoia, his struggle with depression. Eventually, I would read a biography of his life and learn that at times he could be abrasive, even to friends. I didn’t see that side of him. I only saw the pleasant, wistful side of a man who for some reason wanted to share thoughts and wine with an American kid in Pamplona. Perhaps he was resurrecting parts of his own youth by quizzing me; perhaps he was fishing for material he could use in his own writing. I think he was just naturally curious.

Hemingway would never sweep me away with his stories and novels — others did that. But Ernesto, the man in the Pamplona plaza, affected me in another, more personal way. Until I’d met him, no one had ever taken me seriously as a writer — I was too young and unformed. But on that day in 1959, he patiently listened to me babble on about my first writing efforts, my adventures on the road, my hitchhiking across America and Europe. I was naive and pathetically ignorant of so much, but he didn’t seem to mind.

I have forgotten the sound of his voice but I still remember his last words: “The writing — keep at it!”

•

Ron Arias

First published as “Hunting Hemingway,” AlternaCtive PublicaCtions, University of California Merced, March 12, 2009, based on an expanded version of “Red Wine, Hemingway and Me,” People, Oct. 14, 1985, and included in the non-fiction collection My Life As A Pencil, Red Bird Chapbooks, 2015. Drawing by Ron Arias [Ron was 17 when he met Hemmingway.]

A great narrative about a special place and a special man. Thank you.

A very nice description of a meaningful encounter when what went unsaid was perhaps more significant than what was actually verbalized. Thanks for sharing this. I enjoyed it very much.

Little brother, I have always been extremely proud of you. Riding the motorcycle from Barcelona to the French border, after attending the University. Mommy was excited that you met Hemingway, she read his books! Write on!

Bob

Colombia 64-66