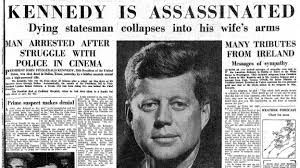

Death of JFK — Our Experience in 1963

•

Death of JFK

I think Peace Corps Volunteers all over the world had a similar experience. In Addis Ababa, we learned via a phone call about the assassination, and I got out my shortwave radio to learn more. There were six of us in our house, and we all crowded into my room to listen to the staticky radio. Very frustrating.

I think Peace Corps Volunteers all over the world had a similar experience. In Addis Ababa, we learned via a phone call about the assassination, and I got out my shortwave radio to learn more. There were six of us in our house, and we all crowded into my room to listen to the staticky radio. Very frustrating.

Afterward, there was an outpouring of grief and sympathy from our friends. Schools were closed on the following Monday, and on the following day, those of us who were teachers faced a barrage of questions from our students. Actually, it was a useful teaching point about American life and democracy

— Neil Boyer (Ethiopia 1962-64)

•

Ask not

As a Peace Corps Volunteer, I was assigned to La Plata, a difficult-to-find village on any map, set in the foothills of Colombia’s Andean mountains. On this soon to be fateful morning of November 22, 1963, I had taken a bus into Neiva, the Departmental capital, to obtain some governmental authorizations for Community Development Funds for one of our projects. Like most every bus in our area, firmly set above the driver’s head were three pictures with Christmas tree lights around them: Jesus, the Virgin Mary, and President John F. Kennedy. Later that afternoon, about 3:30 PM or so, before boarding the bus for the trip back, I stopped at a newsstand next to the Hotel Neiva to see if it had a recent copy of Time Magazine. There was one copy left!

As a Peace Corps Volunteer, I was assigned to La Plata, a difficult-to-find village on any map, set in the foothills of Colombia’s Andean mountains. On this soon to be fateful morning of November 22, 1963, I had taken a bus into Neiva, the Departmental capital, to obtain some governmental authorizations for Community Development Funds for one of our projects. Like most every bus in our area, firmly set above the driver’s head were three pictures with Christmas tree lights around them: Jesus, the Virgin Mary, and President John F. Kennedy. Later that afternoon, about 3:30 PM or so, before boarding the bus for the trip back, I stopped at a newsstand next to the Hotel Neiva to see if it had a recent copy of Time Magazine. There was one copy left!

In my excitement to read while paying for it, I paid little attention to a wildly gesturing sales clerk, arms all akimbo, shouting at me in desperation words like muerto (dead), John F. Kennedy, asesino (assassinated), en la cabeza (in the head), and jabbing his fingers to his head for added effect. Thinking the man was either deranged or just anti-American I gave him no attention and left rather than create a scene. He kept shouting after me, obviously quite upset at my dismissive attitude. I was self-absorbed, focused entirely on having Time Magazine all to myself before having to share it with my site partners.

Upon arriving in La Plata, I noticed the streets were empty in the main plaza, but a huge crowd had formed at the front door of our house just down the street. Some 3,000 people lived in La Plata and they all seemed to be at our front door! My first thought was that something had happened to my site partners, Frank and Steve. As I moved closer, the crowd made way for me. No one spoke. Some reached out to put a gentle hand on my shoulder, lightly touch my hand, or to murmur something as I passed by, their faces prefiguring something that had to be unspeakable. No thought crossed my mind about anything the sales clerk had shouted to me in Neiva.

Once inside our house, I went into a room where my site partners were seated. I was relieved to see that they looked just fine, no different than when I had left them earlier that day. They were huddled over a small short-wave radio, saying nothing, but moving to make room for me to sit next to them. Now, seeing them up close, they appeared stunned and were furiously working the radio to pick up clear stations. They tried BBC, then VOA, then Radio Cali, and Bogota. At each stop on the dial, brief bursts of news came through: shots in Dallas, Texas; the President was in a hospital; then Air Force One was taking off for Washington, D. C. We couldn’t connect the dots.

At one point, the front door opened and plates of food and coffee were silently slipped into us. No faces just extended arms.

Before midnight, there was a gentle knock on the door. It was the Mayor. He asked if we might take a moment to step outside. Upon doing so, it became clear that the entire town of La Plata was out there. The Mayor, hesitant, cleared his throat for what must have been a long minute before finally reading a Proclamation expressing a deep and profound sorrow on the part of every citizen in La Plata for the incomprehensible news that ”the sons of John F. Kennedy now had to bear”.

The three of us still had not understood fully what had happened. We stood there rather bewildered. Then, Dona Lucia Perez, a woman who lived down the street, stepped forward. She asked us to look back and upward to our front door. There, stretched above it was an American flag. To make sure we could see it in the darkness, everyone who had a flashlight put their beams onto it. The effect of all those lights in that midnight environment was rather surreal. It was at this point that our denial finally gave way to the inevitable and we connected the dots: the man, who with one simple request “ask not …,” had compelled us to reach into the unknown was no longer with us. Although we were surrounded by what seemed the entire population of La Plata, we now felt alone.

Soon afterward, my site partners completed their tours and returned home, entrusting the flag to my care. It is 4’ x 4’ in dimensions, made of rayon. Where Dona Lucia, a poor woman, obtained the materials to stitch the materials together without a sewing machine by the dim light of a candle, and how she knew that it had to have 13 bars and 50 white stars on a field of blue in the upper left-hand corner, I never knew — nor asked. Over the next 18 months of my assignment in La Plata, along with two new site partners, Andy and Bob, we became one with her family of 8 children. Whenever there was meat on the table, it went first to her beloved husband, Don Luis, a one-eyed itinerant field worker—and none of us complained. Their house had no TV or radio . . . familial love seemed to be the main form of communication.

Back home I flew the flag from the front door of our home in Washington, D. C. every Memorial Day, July 4th, and Veterans Day, and I still often take it to reunions of our Peace Corps group. In spite of its exposure to wind, sun, and sudden thunderstorms over the past 58 years, it has never required any repairs. When I see it, this flag reminds me of JFK’s admonition that “the burden of a long twilight struggle” is ever with us, its outcome always uncertain, painful and costly.

— Jerry Norris (Colombia 1963–65)

•

In what may be the last play Shakespeare wrote alone, at THE TEMPEST’s end Prospero exclaims “We are such stuff that dreams are made on, and our little life is rounded with a sleep.”

His teenage daughter, Miranda, hopeful and wise says: “Oh, wonder! How many goodly creatures are there here! How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world, that has such people in ‘t.”

Something here to think about twining poetry into philosophy from our youthful enthusiasms. Once upon a time never fades away.

“Don’t let it be forgot, that once there was a spot, for one brief shining moment, that was known as Camelot.” — Alan J. Lerner

I cannot improve on Jerry Norris’ memories of that painful day, but I will add my own.

I was in a movie theater in Asmara, Eritrea (then a province of Ethiopia). There were a few Italians and Americans in the audience; all other faces were darker. For this reason, I was surprised to see white faces appear in the aisles, beckoning to Americans to come out to the foyer.

When we gathered—10 or 15 Americans (including U.S. soldiers from a nearby Army base) — someone broke the news. One volunteer said he lived close and he would let us listen to BBC and VOA on his shortwave radio. Five of us gathered beside his radio and listened to the awful facts until they became repetitive. I went home to my hotel, wondering if by morning the Russians would attack America.

The next morning I read the news, first in Italian and then in an English version of the local paper. Other Americans gathered, but we did not speak. A silent crowd of Eritreans and Italians gathered in front of the cathedral. The doors were draped with an American flag.

I went by to my village, carrying a large photo of JFK that I posted in front of our house, draped with black cloth. Visitors stood outside for several days., A few came inside to express their grief. All barriers between us were removed.

Over the weeks and months that followed, I worked feverishly to teach, prepare lessons, and prove myself worthy of Kennedy’s vision. I did not see films about the assassination until I had returned to the U.S. eight months later. I was touched to see the diminutive figure of Emperor Haile Selassie leading the parade of mourners. I absorbed these images much later than most Americans did, but they remain as painful as though it happened yesterday.

You might assume that I remember the name of the movie that was interrupted in the Asmara theater—but I cannot. This was my moment of truth, the line between hope and despair, past and future, forgetting and remembering. After this moment, I remember it all.

Dan Wofford, Peace Corps Family Member, Ethiopia 1962-64.

Our family moved to Addis Ababa in June 1962. I was just seven years old and on an adventure not of my choosing. One that certainly changed my life and that of my older sister, Susie and younger brother David. My parents, Harris and Clare Wofford, had decided to accept Sargent Shriver’s request that my dad direct the planned Peace Corps program in Ethiopia and to represent the Peace Corps in Africa.

Very late on the evening of November 22, I was sleeping in my sister Susie’s room close to the hallway phone in our home outside of Addis on the foothills of the Entoto mountains. She had a friend over for a sleep-over and was in my room that had two beds. Because of that friend’s sleepover, I was a witness to my father’s first reaction to JFK’s assassination.

I was awakened by a the phone ringing very late at night, perhaps even past midnight. It was a call from one of my father’s deputies — I believe it was from Ed Corboy, who had a shortwave radio and called my father to report on the news of the assassination. My father’s anguished tone and the words, “No, No, No…” have stuck with me all these years later. Like all the PCVs in Ethiopia — my parents and we children — felt very, very far away from the United States that night and the days that followed, which made the sense of loss even more powerful.

My father learned from the US Embassy that the Emperor was flying to DC for the funeral; he rushed to the airport only to miss catching the Ethiopian Air Lines flight to DC by minutes It was the first of three terrible losses to come later in that transformational and turbulent decade of leaders he had believed in and worked with. Despite these blows, my Dad never lost his optimism and belief in the great possibilities and potential for change American Democracy offers. In some ways, I am glad that he’s not with us today and that his enduring optimism about America didn’t have to be tested by the GOP’s shocking anti-democratic turn towards authoritarianism.