Prudence Ingerman — Peace Corps/Bolivia

PEACE CORPS BOLIVIA I – 1962-1964

1

Training and a Grand Welcome

It was March 1, 1962, and I had almost forgotten about my application (# 102) to this new Peace Corps idea of President Kennedy, so when I received the following phone call, I was stunned.

“Congratulations,” said a woman’s voice, “you have been selected for the first Peace Corps project to Bolivia. Can you be ready for training in Oklahoma on March 16th?”

I babbled, “B..Bolivia? Oklahoma? March 16th?” I must have sounded like an idiot.

“Yes, the training is in Oklahoma. It starts on March 16th. ”

“ Well . . .” I tried to think intelligently, “yes . . . yes I can be ready.”

“Fine, I know this is short notice, so please look for an important packet in the mail in the next day or two.”

She hung up and I sat there breathing hard, thinking . . . “Bolivia! Bolivia? Llamas spit and the women wear funny hats.” That’s all I could remember from 5th-grade geography.

What to do first . . . think . . . oh my . . . make a list . . .

- Quit my job at Mt. Auburn Hospital,

- Tell friends,

- Call my father, and

- Pack up my life in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I had driven my 1940 Desoto there in the fall to seek my fortune.

Such a flurry of activity made even more intense once the packet arrived. I had to get fingerprinted . . . quite exciting . . . and see a doctor, and fill out and return several forms by special delivery.

I did all those things, drove back to Pennsylvania to do the serious packing, and to say farewell to my father who was highly amused that I, with no Spanish whatsoever, would be going to a Spanish-speaking country. He, after all, was the Spanish language expert in the family, having studied in Spain for several years.

So, at age 21 and a half, with a new suitcase, guitar, and pounding heart, I boarded my first plane ride ever for Norman, Oklahoma. The university there was chosen as a training site because of the large number of Bolivian students, who sat with us at every meal, and were paid to speak only Spanish, and encourage us to do the same. This left most of us eating silently for many days.

Every morning we had language classes for three hours. I protested when I saw my name on the list for the Advanced Spanish class, “I have never studied Spanish at all.”

The language teacher referred to a paper and said, “Hmm . . . it seems you have quite a good base of language instruction, so this is where you belong.” Righ . . . my “good base of language instruction” consisted of five years of French and three years of German plus about twenty words in Swahili, when I was considering going to Kenya with a Harvard language project.

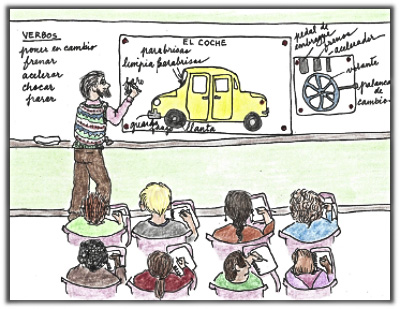

Learning the names of parts of the car in Spanish

Looking back now, from my vantage point of having been an innovative and successful English language instructor for more than 20 years, the instruction we received was both intense and purely dreadful. Each class went like this: The professor would put up a huge picture of the day’s topic. “Today we will study the car.” Then he would name and label every part of the car on the chart (in Spanish, of course): Windshield, bumper, fender, gear shift, etc., and then give us all the verbs related to a car: Go, stop, brake, crash, turn, etc.

There was always a test the next morning, on the previous day’s vocabulary, and then he would put up another large picture. “Today we will study the human body.” Again we feverishly drew pictures and labeled every part of the human body, and then he added all the verbs we could come up with: Breath, gasp, walk, fall, vomit, cough, choke, die, pant, swallow, digest, etc. I must have made hundreds of flashcards, I clearly remember waking in the night and shouting, “DEDAL!” (thimble). You must admit this is not a powerfully useful word, but I learned it when we did clothing.

In this class, there were native Spanish speakers: Rose Navarro and Oscar Garcia, and Chiquita Valdez plus three or four others who had seriously studied Spanish and had even studied abroad. In every class, these fluent speakers would inject Spanish synonyms used in Mexico or Columbia, or Spain, which only added to my confusion. At times I quite envied the Beginner class with their memorized dialogues, and ability to glance at their watches and say brightly, “¡Caramba! ¡Ya son las once!” (Holy smokes, it’s already 11!)

One had to achieve a 2.5 level of language proficiency with the Foreign Service Exam, and this was a particular challenge for Kathy Connelly, a vivacious 5’11” psychiatric nurse from Chicago, with black curly hair and large blue eyes. She struggled mightily with Spanish, yet somehow finally achieved the required score on the language exam. She was our only psychiatric nurse and was scheduled to fill a much-needed spot in the nursing school in Bolivia. She felt a lot of pressure and she studied very hard.

In the afternoon we received an overview of the politics, economy, and sociology of Bolivia, but much more intensely we studied specific health problems, as we were a public health project. The Peace Corps only goes to countries that ask for technical help, so the Bolivian Ministry of Health had submitted very specific needs to the Peace Corps central office in Washington, D.C., thus, our group was a rather weird (and wonderful) conglomeration of two pharmacists, several well drillers, pipefitters, civil engineers, registered nurses, practical nurses, dental hygienists, and an oddly or incompletely educated group labeled health educators, of which I was one.

I remember when Sargent Shriver and Bill Moyers came to Oklahoma and sat under a tree watching us. This was truly a fishbowl experience because aspiring but unsuitable volunteers were “selected out” and disappeared in the night. In the morning one’s language class was often minus a body or two, which was quite disconcerting. These sudden disappearances acted as powerful catalysts for the rest of us to participate even more enthusiastically in EVERYTHING, at every moment. We sang rounds while waiting for typhoid shots, we bolstered up anyone who was feeling a bit down, we spoke Spanish as much as we could to each other, and we sang “We Shall Overcome” and “Last Night I Had the Strangest Dream” and “Solamente una Vez” with great passion on bus trips, but we were ever mindful of the eyes watching us.

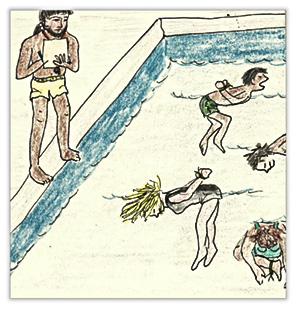

Drown-proofing

So of the original fifty-three who went for training, eighteen were weeded out during the two months in Oklahoma and the one month of Outward Bound type activities in Puerto Rico.

In the illustration you can see us mastering drown-proofing, a survival swimming technique that involves floating for twenty minutes with hands tied behind our backs and slowly, slowly breathing out and then giving one kick, strong enough to lift one’s head, to get a quick breath, then lowering one’s head down and slowly, slowly breathing out again. We also had to do twenty minutes with legs tied. I’m sure the Peace Corps had no idea that this exercise was also teaching us how to meditate, although we were not at all sure how we would use drown-proofing in land-locked Bolivia.

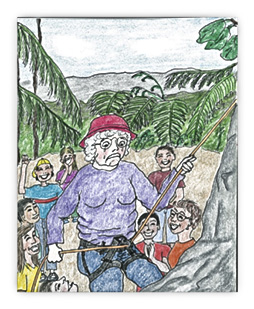

Ann rapelling

We were the loudest cheering squad in the world as we encouraged our oldest volunteer, Anne Peabody, age 64, when it was her turn to rappel down a rock wall, tears streaming down her face. When our training ended, we were transformed into a tightly bonded group of 35 official Peace Corps Volunteers. We were excited, proud, and ready.

After we slowly descended the steps of the plane onto the tarmac in La Paz, Bolivia, we solemnly stood together with our hearts pounding in the rarified -13,000 foot altitude and sang the Bolivian national anthem by heart. A few days of orientation followed in La Paz, and we practiced two new, but vital, instructions: DON’T DRINK THE WATER. DON’T PUT ANY PAPER IN THE TOILET. A few of us brushed our teeth with 7-Up. A few others admitted to fishing out a disgusting paper from the toilet.

Then we heard that we were going to be welcomed by the Bolivian President, Paz Estensorro himself. Oh, my word. How often does one meet the President of a country? We arrayed ourselves in our most unwrinkled clothing and were bussed to the Presidential Palace, and ushered into an enormous room with about fifty chairs lining three walls. On a raised platform against the fourth wall, there were five ornately carved wooden armchairs, flanked by large flags of the country. We sat silently in this church-like atmosphere and then suddenly, in came the presidential entourage (five men). We stood respectfully. The center gentleman (the President) motioned for us to sit down and then gave a moving speech of welcome and gratitude for us giving up two years of our lives to serve his country for no pay. Then he stepped down and came around to the first volunteer, Tom Shabarum, who jumped to his feet. President Paz Estensorro shook his hand and said, “Bienvenidos a Bolivia.” Tom stammered out, “Mu . . . muchas gracias, Señor Presidente.” The President continued around shaking hands, smiling and graciously welcoming each of us. When he came to our incredibly tall, gorgeous Kathy Connelly, she leaped up, grabbed his hand, pumped it vigorously, and said, “Much-o gusto, Seen-yore Prayzadenty, como estás?” Thirty-four new Peace Corps volunteers and country Director Derek Singer gasped at this HORRIBLE, and totally disrespectful, use of the familiar tu form of the verb. We were surely going to be evicted from the country for this breach. To our astonishment, President Paz Estensorro smiled as he looked up from his 5’2”, and said, “Muy bien, niñita, muy bien,” and patted her hand. A collective sigh and he continued around smiling.

As I mentioned, Kathy was to teach psychiatric nursing, surely a challenging topic even in English. She did manage and her students loved her dearly. She had, however, only a very limited command of one Spanish verb tense so this is how she taught:

Kathy teaching

“La semana pasada nosotras estudiamos (Last week we study) -a vigorous waving backward of one hand over her shoulder accompanied by the word “¡PASADO!”

or

“La próxima semana nosotras estudiamos (Next week we study) – a vertical hand now leaps forward as if over a fence “¡FUTURO!”

Can you believe it, she taught psychiatric nursing for two years in the present tense with much hand waving of “¡PASADO!” and “¡FUTURO!” Amazing.

2

Modern Surgery

In 1963, the Civil Rights Movement and the momentous March on Washington were galvanizing people in the United States, but for me, all that excitement and energy were as distant as the moon, because Patty Schwartz (5’10”, willowy with long blond hair), and I were working intensely as Peace Corps health volunteers in a small town called San Borja, in northern Bolivia. This town was semi-tropical, and, depending on which season, had dusty or muddy roads, even around the small, pretty central park. It had one Catholic Church, several corner stores and two dentists. It also had a large building of particular interest to us, because it was our designated “hospital.” But when we arrived, this structure had no doors, and the empty rooms were all open to freely roaming pigs and chickens, and the corners were littered with garbage.

Thin, intense, mustached Doctor Miranda was in San Borja doing his “año rural”, the required practicum year, before receiving his final diploma in medicine. He was there with his wife and several small children, and he welcomed us, and was very excited to have what he thought were two American nurses to work with him. Together we decided what we would need to transform that empty building into a real working hospital. We made a comprehensive list which included doors, windows, medical equipment, beds and bedding. We sent this formally worded document off to the Ministry of Health in La Paz, on the weekly plane.

We were prepared to wait for quite a while for some response, so we started to plan health talks and meet more people. We were sitting quietly one day in our rent-free dwelling place (an old abandoned movie theatre) when one of Doctor Miranda’s children knocked politely at the door.“Mi papi dice que vengan a la oficina,” (Papa says come to the office).

What we had not yet discovered was that Dr. Miranda was crazy, passionately crazy, insanely crazy to perform any kind of surgery, the more complex the operation, the better.

At this point I need to mention that although I had not completed the nursing course at Jefferson Nursing School in Philadelphia, I had finished the surgical rotation and had liked it immensely.

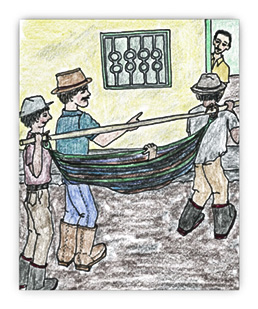

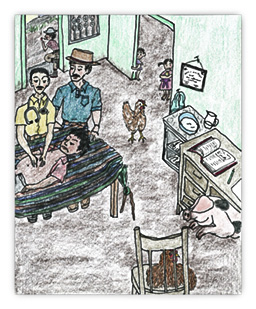

A patient arrives at the hospital

When we got to Doctor Miranda’s office, we saw him directing two men who were carrying a long pole from which was suspended a filthy hammock with somebody inside it. They lowered the hammock onto a large table, and we were introduced to Anselmo, a man in his late thirties. His clothing was unspeakably dirty and he had a hugely distended abdomen. He was moaning with pain. I clearly remember how the filthy hammock was left underneath him, draping right onto the dirt floor.

Diagnosis: bowel obstruction and peritonitis

Doctor Miranda examined Anselmo gently, and Patty took his blood pressure and I took his temperature and pulse. The examination and the three vital signs were alarmingly abnormal. Diagnosis: bowel obstruction and peritonitis.

Patty sat at Anselmo’s head and took frequent blood pressure checks. The doctor’s wife busied herself with sterilizing his surgical instruments, and Doctor Miranda and I scrubbed our hands and arms. We had no gloves. With topical Novocain as the only anesthetic, we performed a bowel resection and installed a very rustic colostomy with adhesive tape and a plastic bag. During this very long and complicated surgery, chickens ran about clucking occasionally, the doctor’s small children and people passing on the street watched from the open doorways. I was so busy assisting, I hardly noticed a large pig that grunted from time to time from its haven under Dr. Miranda’s large desk.

The surgery was successful and Anselmo was able to sit briefly and take a few steps the next day.

Several weeks later, the Minister of Health came on a specially chartered cargo plane, and with great ceremony, inaugurated the hospital. He brought:

two new doors,

six small windows,

five beds,

four mattresses,

five sets of sheets,

six blankets,

four hospital gowns,

three pillows,

five pillow cases,

a delivery table,

one iron baby crib,

an OR table,

a cabinet with glass doors,

three large rolls of gauze,

two rolls of adhesive tape,

twelve syringes,

ten vials of morphine, and

four of Novocain,

an IV pole,

five liters of normal saline and tubing,

a large pressure cooker,

four liters of alcohol, and

five liters of iodine.

This was approximately half of what we had put on the list, but Doctor Miranda was not alarmed in the slightest. We were all set.

Using only local anesthesia like Novocain, which we often had to borrow from the dentists, in the eight months that I was there, we performed sixteen major operations: several appendectomies, repairing and closing Anselmo’s colostomy, another bowel resection on a robber who had been shot in the abdomen, the setting of several compound fractures and the repair of machete cuts after some drunken brawls.

Here is the procedure pre-surgery:

- Contact el Diablo, if evening surgery. More about him is coming.

- Be sure the home-made scrub tops are clean.

- Be sure the instruments are all clean.

- Cut and fold at least 50 gauze pads (4 x 4).

- Be sure the home-made drapes are all clean.

- Make sure Santiago is available. Santiago was the indigenous man who lived behind the hospital and helped lift patients and do other assorted tasks.

- Be sure there is sufficient propane for the little one-burner stove.

- Find the adhesive tape.

- Put underlined items 2–5 in the large pressure cooker, put the lid on, light the stove and and sterilize it all for twenty minutes.

Meanwhile, Dr. Miranda would strip to his waist, and his wife and I to thin little tank tops. The three of us scrubbed our arms thoroughly past our elbows, with harsh soap and cold water, and called for Santiago.

He entered with an ax, turned off the stove, waited for the pressure on the dial to go down, and then WHAM, with the ax, he loosened the lid, all the while we were cautioning him to not touch anything, as he finally removed the lid.

We waited a few more minutes for it all to cool, then we removed and put on the scrub tops which were the first items. We then helped the doctor’s wife to arrange one sterile drape on a small table for the instruments and gauze pads.

In the middle of all this preparation, Patty (our only RN) with Santiago led the wide-eyed, terrified patient in, and helped him or her to lie down on the OR table. Patty spoke soothingly as she administered a hefty injection of morphine, then she perched herself on a wooden box at the patient’s head and checked the blood pressure. Her other job was to blow air into any serious non-breathers, if necessary.

A wizened, not very tidy, health-related person called Don Chapi appeared to start the IV. We learned he had been a medic in the Chaco war, so he had some training. In San Borja, if you needed an injection of any kind, you would buy your medicine at a corner store, take the little glass vial to Don Chapi, and for a small fee, he would file off the top of the vial, withdraw the medicine in a hopefully sterile syringe and then inject it. He also knew how to find veins for the IV solutions, so he was a necessary part of our OR team.

Dr. Miranda’s wife, with no medical training, was also vital, as her job was to pass instruments to the doctor upon demand, like a scrub nurse. She was willing and able, but only until the first sight of blood, when she would turn green and become light-headed and have to sit down on another wooden box in the corner, until she recovered (never fully) and we, of course, had to keep warning her not to touch anything, because she was needed to retrieve the remaining sterile objects from the pressure cooker.

My job was to stand opposite Dr. Miranda and actually assist. I felt excited and willing, but grossly under-qualified to help in this way.

One small problem was the absence of caps, masks, and gloves, but Dr. Miranda was all enthusiasm for a new German method he had read about in a medical journal, and so, by thoroughly scrubbing our hands and arms to the elbow, and painting them generously with iodine, we did all the surgery bare-handed and bare-headed. No masks.

So now you have the scene all prepared in this hot little town.

It is important that you remember that the weekly Lloyd Aereo Boliviano flight arrived and left our little village of San Borja only on Tuesdays.

It was early on a Wednesday morning.

“Prudence, I don’t feel so great.” Patty sat quietly holding her stomach.

“Maybe you ate something bad.”

“I dunno.” She sipped a little tea, while I ate some bread and a hard-boiled egg, and then we walked over to the hospital to check on the patients under the night care of the two nurse’s aides we were training.

By noon, Patty was walking bent over and clearly in pain. Around three P.M, Dr. Miranda examined her and announced, “It’s an acute appendix. We have to operate, but we’ll wait until tonight when it is cooler and there are not so many bugs.”

So, I ran all over town and borrowed Novocain from the dentists. Then I had to go find El Diablo (The Devil).

The electricity in San Borja was run by one generator, which was operated by a man called El Diablo, who thought himself God’s gift to young women. He was tall, dark, with a wickedly-bushy black mustache — quite handsome, really. His job was to turn on the generator, which controlled all the electricity in San Borja, at dusk, and turn off the generator around 10 pm, which became everyone’s bedtime. The timing of these two tasks depended totally on Diablo’s state of sobriety. Anyway, I found him draped comfortably around several beer bottles, already rather sloshed at 5:30 that afternoon.

I greeted him, “Buenas tardes, Diablo.”

He waggled a hand at me.

“Diablo, Dr. Miranda says you have to leave the lights on tonight, because we’re going to operate.”

“Maybe I will . . . and maybe I won’t,” he slurred and slurped his beer lovingly.

“Diablo, tonight we are going to cut open the gorgeous Margarita (Patty), and we need the lights left on, at least until midnight.”

Diablo thought for a moment of the tall blond nurse who had firmly spurned his amorous advances, “Well . . . maybe I will and maybe I won’t.”

“Diablo, if you do not leave the lights on, President Kennedy himself will come down here and shoot you in the head!”

A pause for thoughts to crystalize boozily, “All right, all right, I’ll leave the lights on.”

And he did! A miracle, really.

The surgery preparations were underway just as I have already described, when in walked disheveled Don Chapi, a half-smoked cigarette hanging from his lips. Patty, already on the OR table, was startled from her morphine daze and said, “Prudence! What is he doing here?”

“It’s okay, it’s okay, he’s just going to start the IV, that’s all.”

Patty on the operating table

“Prudence, watch him! Watch him!” Patty hissed and then slumped back down, eyes fixed on Don Chapi.

There really was no need for such panic. Don Chapi competently started the IV, then sat on Patty’s wooden box and smoked several cigarettes during the entire surgery. The operation proceeded without mishap, but without our mobile oxygen provider and blood pressure monitoring unit, who was lying there quite relaxed and chatty.

The next day we had another emergency appendectomy and Patty, one day post-op, sat on the wooden box and took blood pressure. No oxygen was required. A good thing.

3

An Unforgettable DC-3

I have already described a bit of the life in the new hospital in the small town of San Borja, Bolivia but let me tell you about one special flight from the capitol, La Paz, whose airport is at 13,000 feet. The small two-engine DC-3 leaves La Paz, rises very swiftly for five minutes to get over the 23,000 foot peaks of the Andes, and then, just as dramatically descends to San Borja, which is almost at sea level. All this up and down happens in less than one hour.

On this particular flight, there was an odd assortment of passengers: A group of Swiss hikers, a priest, two nuns, me — the odd American — and the rest were Bolivians, including my seat mate sitting on the aisle seat. We were only about five minutes in the air and I noticed some strange activity. The priest had gotten out of his seat and was walking up the narrow aisle blessing people and the two nuns had fallen to their knees and were fingering their rosaries and praying audibly. Not having a clue, but thinking that perhaps this was normal Catholic airline etiquette, I still thought it was strange and asked my seatmate, “¿Qué pasa?”

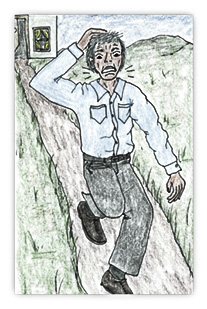

The stilled propeller

He pointed out the window and announced, “La hélice.” Instant vocabulary lesson, for there, between my window and the severely stark and snow-covered Andes, was one of the two propellers, just standing there, not doing its thing at all.

Without any break whatsoever in our smooth flight, the captain had compensated so beautifully for that engine failure, that we were already headed back to La Paz, and were safely landed within just a few minutes. Everyone piled out of the plane, falling on the ground, kissing it and exclaiming gratitude to all available gods. If I were not already a staunch Quaker, this would have been a moment for instant conversion to some kneeling religion, I tell you. Anyway, within minutes some mechanics arrived, fixed the defunct propeller. and we all got back in that same plane, and off we went! No problem!

Later, upon retelling this adventure with some Peace Corps guys with aeronautical knowledge, they assured me, “Don’t worry, a DC-3 can glide.”

Yeah, right. At 23,000 feet where would we glide to? I was not eager to test this.

4

LEPROSY AND LOSS

For some reason, the Peace Corps in Bolivia had a hard time placing me in a location where I felt confident enough to be effective. Other volunteers stayed in their sites for the entire two years, forging wonderful friendships and working their way out of their jobs (the Peace Corps goal), but I, with a combination of immaturity, limited education and experience, felt awkward and ineffective and was shifted around more than others.

Our overall Peace Corps project was public health. At my first site, I had walked around an indigenous area of the southern city of Tarija. My task was to observe this area for its health needs and to write a recommendation to the Minister of Health, which I did.

Then I taught English at a kindergarten and on the radio. For the latter I gave phrases and then paused for the listeners to repeat them. I had to laugh whenever I walked down the street and heard, as I often did, “Good mawnin, meestair [pause, pause] How are you? [Pause, pause] Fine, tenk you [pause, pause].”

Next I was assigned to San Borja with RN Patty Schwartz. That also only lasted about eight months.

In a final effort, the Peace Corps administration sent me to Los Negros, a colony of patients with Hansen’s disease — leprosy. I read all I could about the disease and about Father Damien’s life on the Hawaiian island of Molokai (where he died of leprosy), and of course I was terrified of catching it.

Leprosy is the least communicable of all communicable illnesses. One has to live very closely with infected people for a long time to contract it. I learned that the nursing sisters who took over Father Damien’s work on Molokai followed two strict rules from the Mother Superior — “Don’t eat with a patient. Don’t eat food prepared by a patient.” Abiding by these two guidelines, and also taking into account the natural separation of the nuns’ cloister from the living areas of the patients, no nursing sister on Molokai has ever contracted leprosy, even today. I was determined to follow those two rules and stay as isolated as possible.

This colony, Los Negros, had about seventy patients. A group of American missionaries had been operating it, but now it was being handed over to the Peace Corps. There was still one older missionary couple living up the hill, who had remained to assist with the transition. When I arrived, there was already a well-bonded group of four Peace Corps volunteers, who all lived in a large, comfortable house about a kilometer from the colony, and who spoke English all the time together. Not to boast, but my Spanish, by this time, was considerably more fluent than theirs.

With my label of Health Educator, I was not sure exactly what I was to do at Los Negros, so again, I walked around and observed and talked with patients outside their small mud huts. I became interested in their feet, which were often deformed, and I was appalled at both the lack of shoes and the wretched condition of those shoes they did have.

One result of leprosy is peripheral neuropathy, a nerve damage that causes numbness, weakness and pain especially in the extremities, similar to what can happen to anyone with poorly managed diabetes. Blisters or sores on the feet are not felt and therefore often go unnoticed until they have become infected. Due to poor circulation, these wounds are slow to heal (or never heal) and in severe cases, gangrene can set in and require amputation. It was very evident to me that many patients at the colony had feet that were inviting disaster.

One day, I struck up a conversation with a patient named Segundo. “The shoe situation is terrible here. What do you think?”

He nodded his head, “Nothing to make shoes out of.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, you need leather, buckles, good knife and rubber for the soles.”

“How do you know all this?”

“Oh, before I came here, I was a shoemaker.”

Well, this started a great partnership. Segundo knew exactly what he needed to start a shoe-making shop, and I made a list with growing excitement. I read as much as I could find about peripheral neuropathy. A few days later, I caught a bus to Santa Cruz, the closest big town, and returned with everything on the list, which included a large, rolled- up cow hide and an old Jeep tire.

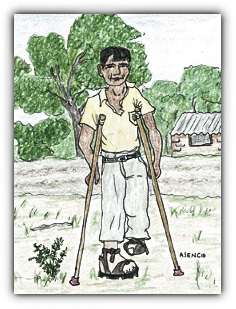

Asencio

The first patient we worked with was Asencio. He was a shy man of forty, who had been in bed for two years, because he had a clubfoot and was also missing all the toes on his other foot, and he had no crutches. He had been the sacristan of a small village parish and was deeply religious, kind and patient. Segundo and I fashioned a protective leather covering for the clubfoot and a special sandal for the better foot. A phone call to the Peace Corps office in La Paz resulted in the arrival of a pair of crutches. Imagine Asencio’s joy at being able to stand erect, walk to the colony dining room for meals, and go out to the field to watch the soccer games. He was very happy. We were all very happy.

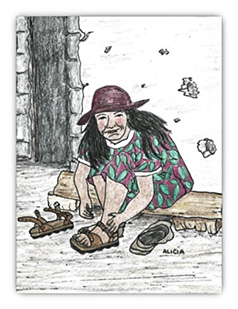

Alicia

Our second patient was a large, friendly woman named Alicia. I had her stand on a piece of carbon paper on top of a plain sheet of paper so I could identify any problem areas of where she applied pressure. Segundo and I studied these and made orthopedic sandals for her using rubber from the old Jeep tire for the soles.

I also noticed three children ten to thirteen years old with mild cases of leprosy, so I started a school. Some adults who could not read or write began attending as well. I was quite busy, and felt I had finally found meaningful, on-going work in which my creativity was called upon daily. I was quite busy and very happy.

“The shot the President!”

One afternoon in November, we had all finished work and were starting to prepare our dinner when all of a sudden the missionary husband came running down the hill from his house shouting something We rushed out to see if he or his wife had been bitten by something or had had a horrible accident of some kind. As he got closer, we heard him yelling, “They shot the President! They shot the President!” None of us reacted at all to this news. Bolivia is a country where there are frequent revolutions, so we were not particularly perturbed.

He paused in front of us, bent over, hands on his knees. He looked up, panting and struggling to get the words out, “They . . . they shot the President!!”

Again, nothing from us. Clearly something momentous had happened, from his distraught expression.

“The President! President Kennedy!” He could hardly speak. “They shot the President! Turn on the radio!”

We raced in to our radio and turned it on. I sat there translating this horrifying news from Voice of America, and it wasn’t until much later that I realized that it was Portuguese I had been translating. We were all in shock.

Our shared sadness

At this time, Bolivia was very pro-America because of the Kennedy administration’s aid program, and the fact that John Kennedy was Catholic, both of which endeared him to many at a more personal level.

All households in Bolivia must display a large flag of the country for special holidays like Independence Day. For more than a week, that November of 1963, there was a Bolivian flag displayed in front of every house, but not flying freely. These normally-cheerful striped banners were tied down securely with black strips of cloth. It seemed like the whole country was in mourning. Many people wore black armbands, and total strangers stopped us on the street and hugged us, weeping with sadness for our deep and shared tragedy.

•

Prudence Ingerman is the author and illustrator of more than a dozen books, all written in her clear friendly manner, and all profusely illustrated.

She lives in central Pennsylvania, stranded now from the family in Canada, California, and Alabama due to the coronavirus. Since re-inventing her life (retirement) she has volunteered several months of each year in Guatemala, training teachers and teaching sex education. She has also taught English to taxi drivers and Business English to indigenous market vendors in Otavalo, Ecuador. More recently she completed knitting 496 small peace pals. These little 6-inch dolls are promoted by the Colorado organization /knitting4peace.org/and are never for sale. They offer comfort and companionship to lonely needy people worldwide.

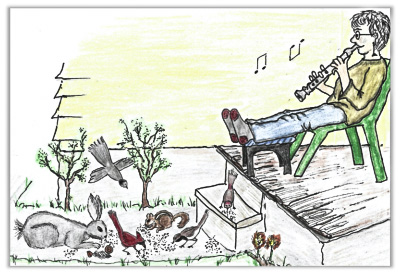

Prudence entertains her friends

She is an avid birder and attracts them (and several very polite rabbits) to her feeders by playing her recorder on her back porch.

What a gem! I’m passing it on to many others, who think they have challenges in life!

This is such a powerful story and it is told in such an engaging manner. Prudence makes it sound “so easy”.and yet we can just imagine the obstcles she had to overcome.

I read a version of this at the Peace Corps Writers workshop week, that John Coyne organized, and was completely taken with the narrative and illustrations. It certainly holds up on second reading, and then some! As I recall there are more of the marvelous illustrations. As I said at that time, some publisher should snatch this up for a book. For now, I’m very pleased to see it here for others to read.

I greatly enjoyed reading this! A great example of making PC work to the needs of the people.

Each paragraph is an insightful historic, social, or personal experience or event presented with engaging warmth by master storyteller Prudence. There’s nothing quite like her “peace pal” dolls.

Thank you, Prudence. Our Peace Corps histories run in a parallel and complementary.manner. . I served in Peru from 1962-64. Reading your non-fiction account was like reading my letters home, only much better. Loved the illustrations.

Patricia Taylor Edmisten, author, “The Mourning of Angels,” a Peace Corps novel set in Peru