Review — ERADICATING SMALLPOX IN ETHIOPIA edited by Barkley, Porterfield, Schnur and Skelton

Eradicating Smallpox in Ethiopia: Peace Corps Volunteers’ Accounts of Their Adventures, Challenges and Achievements

Eradicating Smallpox in Ethiopia: Peace Corps Volunteers’ Accounts of Their Adventures, Challenges and Achievements

Editors: Gene L. Bartley (Ethiopia 1970–72, 1974–76), John Scott Porterfield (Ethiopia 1971–73), Alan Schnur (Ethiopia 1971–74), James W. Skelton, Jr. (Ethiopia 1970–72)

Peace Corps Writers

486 pages; 69 photographs

November 26, 2019

$ 19.95 (paperback)

Reviewed by Barry Hillenbrand (Ethiopia 1963–65)

•

At 465 pages, Eradicating Smallpox in Ethiopia is a hefty and important book which rightfully deserves an honored place on any shelf of serious books about epidemiology and public health. The book tells the tale of the work that some 73 Peace Corps Volunteers did in the early 1970s with The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Smallpox Eradication Program (SEP), a massive project which ultimately eliminated smallpox from the world.

But fear not. The book is entertaining to read. This serious story is served up with large dollops of nostalgia, humor, delightful tales of daring, and loads of information about fighting infectious diseases that — as it turns out in these times of the coronavirus — makes the book very contemporary. Even useful. And for any Returned Peace Corps Volunteer the book offers loads of colorful stories familiar to us all, especially those who served in Ethiopia.

By the early 1970s WHO’s goal of eliminating smallpox from the world was nearly accomplished. The SEP had battled down smallpox in all but a handful of countries. Ethiopia was one of those. Smallpox had been stamped out in major population centers in Ethiopia, but it still raged in the remote corners of the country where there were few roads and meager medical infrastructure. Peace Corps and the WHO agreed to send PCVs into these remote areas to root out the disease.

This book is made up of 18 separate essays by the PCVs who served in the SEP. Some of these memoirists are better story tellers than others, but the stories have been expertly woven together by the four PCVs who organized the book project and by their publisher, Peace Corps Writers, under the direction of editor and book designer Marian Beil. Inevitably there is a bit of repetition in the stories of broken Land Rover axles, tent-invading ants, the administeration of massive numbers of vaccinations in crowded market places, impassable roads, and parasite ravaged guts. But the sum is far, far greater than the parts. This is a rich narrative history of a wildly successful and difficult Peace Corps project. These guys — and, yes, they were all men —were what we ordinary Peace Corps Volunteers called “real Peace Corps.” Peace Corps staff called them “super Vols.” And they were.

The Smallpox Eradication Program used classic public health tactics: find the remaining cases of the disease by intensive search and surveillance of the far corners of the country, and then isolate and contain the disease carriers behind circles of vaccinations. No need to vaccinate the entire population of the country (although in the end SEP administered more than 17 million doses), just the areas around where an outbreak was taking place, and create a barrier against its spread.

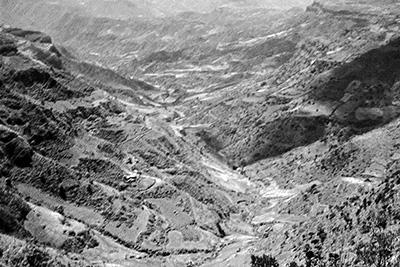

Sounds easy, but it wasn’t. Ethiopia is the second largest country in Africa, but at the time had only 5,000 kilometers of what might be generously classified as all weather roads. More than 80% of the population lived more than 30 kilometers from these roads. There are highlands with 13,000 foot mountains and sweltering below-sea level deserts. And in between endless gullies, gorges, escarpments, and ridges to be transversed.

An escarpment where many smallpox cases were found. 1973. Photo by Dave Bourne

Logistics were a nightmare. WHO handed out new Land Rovers to many of the PCVs in the Program. This was a rare treat because, at the time, most Peace Corps vehicles were reserved for Peace Corps staff in Addis and were off limits to PCVs. The Land Rovers were used to carry supplies to the jumping off points where PCVs loaded their gear on donkeys and, if they were lucky, rode mules up and down escarpments in search of smallpox. Once when there were no mules to rent, a PCV suggest to WHO headquarters in Addis that WHO buy a couple mules for SEP use. The request was sent all the way up to WHO’s Geneva headquarters where it was denied. The PCV, disappointed but determined, ponied up his current month’s living allowance and bought a pair of mules himself, reselling them later after the project was finished.

But mostly it was walking: hours and hours of walking from village to village over foot paths to the far reaches of Ethiopia, places most PCVs never saw.

When I served in Ethiopia in the early 1960s most Volunteers were teachers assigned to schools in provincial capitals or larger towns. Debre Markos, the capital of Gojjam, where I taught, was on the main Addis to Gondar road, had electricity five hours a day. We lived in a mud-walled, tin roofed house with no running water. But it was comfortable and a short walk to the school where I taught.

Occasionally we would hike to visit the more remote villages of our students, but our lives were pure luxury compared to that of the PCVs who worked in SEP. While they had houses in regional towns where they could take a break and restock on supplies, most of their work involved hiking into the isolated regions of Ethiopia in search of smallpox cases.

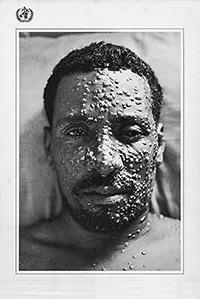

WHO smallpox identification card Photo provided by Peter Carrasco.

They carried cards with pictures of smallpox victims, asking villagers if they had seen any cases. The PCVs hauled tents with them, but often they slept on the floor of regional health centers or, more often, in the mud tukels (round huts) of villagers who offered them welcome, and shared their food with them. The generosity and friendliness of these villagers — often the poorest of the poor of Ethiopia — was boundless and filled the PCVs’ writings, now 50 years later, with a profound sense of admiration and affection for them.

While logistics were a major problem, the PCVs of SEP had to contend with other subtle and often more worrisome issues. Getting permission to vaccinate from local officials in the form of a letter adorned with official stamps in that obsequious — and very essential — purple ink beloved by Ethiopian bureaucrats, was time consuming and required great patience. Even with the letter from government officials in hand (some PCVs also carried a copy of a letter from Emperor Haile Selassie himself urging citizens to get the vaccination) finding cases and convincing people to be vaccinated was a laborious task.

2 1/2″ long bifurcated needle used for smallpox vaccinations in Ethiopia.

Some ethnic groups in Ethiopia were more receptive to vaccination than others. The Amharas of Gojjam and the central highlands, for example, were cool to the idea of letting foreigners jab them with the special WHO-designed smallpox vaccination needle. They required extensive persuasion by the PCVs, even when smallpox was maiming and killing people in the villages. Other Ethiopians eagerly accepted these strange foreigners, mistakenly called “doctors.” In some places when word went out that vaccinations were on offer, hundreds of villagers materialized as if from nowhere and pressed forward with such eagerness to get their vaccinations that it was difficult to maintain order.

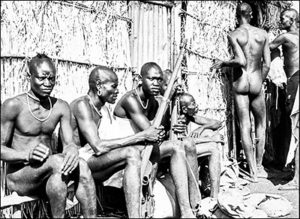

In contrast with today’s Peace Corps which is obsessed with security and keeps track of a PCV’s every move (a task new technology facilitates), in the 1970s the PCVs of the SEP roamed the countryside for weeks on end without checking in with anyone. They did not fret about terrorists (largely unknown in those days aside from the Eritrean independence movement) or robbers (more common but unlikely to bother “doctors”). But a few nervous encounters are recorded. Once when two PCVs, Michael Santarelli and Mark Weeks, were riding in the back of a truck in a totally unmapped area of Gemu Gofa province, they came to a sudden halt. Recounts Santarelli, one of the more gifted writers among contributors to the book,

We looked around and saw 30 or more nomadic Mursi warriors surrounding us. They were tall, muscular and wearing nothing but a rifle or a spear. I mean, they were buck naked, standing there unwelcoming and uncircumcised. Although they didn’t point their weapons our way, it was clear they had us by the short hairs.

But tensions eased. At least one warrior seemed to understand Santarelli’s calm monologue in Amharic about fentata (smallpox), and the need for vaccination.

Continues Santarelli:

Eventually we felt comfortable enough to bring out the vaccine and bifurcated needles.

Mursi warriors, Gemu Gofa, 1973. Photo by Michael Santarelli

The Mursi watched with intense interest as I reconstituted a vial and shook out the needle. To show them how it worked, I vaccinated myself, yet again. Then I vaccinated Mark…. The Mursi examined my arm, touched it, and showed amazement. I pointed to the guy who understood me best and pulled out another needle. Gesturing what I wanted to do, and seeing no objection, I leaned forward and jabbed his arm multiple times. He watched every puncture without flinching. There was a tiny speck of blood at the site, but he stayed strong.

Soon all 30 of the warriors were vaccinated and on their way admiring the bumps on their arms.

A great and colorful Peace Corps tale, no doubt, but, in a sense, it was just another day at the office for the PCVs of the eradication project. Much of the work of the PCVs was a bit more mundane, walking endless miles from village to village searching for smallpox cases, and vaccinating the containment areas. Some PCVs worked alone, mastering not only the difficult terrain and stubborn mules, but the melange of languages and customs. But most travelled with Ethiopian co-workers, public health professionals often called “dressers” or “sanitarians.” They were were invaluable. They shared the difficult trails, administering the endless rounds of vaccinations. Often they were able to provide interpretation into the the other languages of Ethiopia. And they were good company and became close friends with the PCVs. The contributors to the book pay them high tribute. Wrote Stuart Gold:

The WHO and Peace Corps workers of SEP . . . did contribute to the eventual demise of smallpox in Ethiopia, but in fact, it was the nationals on the ground, the translators, the helpers, and the sanitarians who worked alongside us who deserve most of the credit. Without them, we would have been unable to navigate the nuances of the Ethiopian Culture and traditions.They were probably the most important factor in allowing us to achieve our goal.

In their individual essays, the PCVs unfailingly pay tribute to the two beloved and admired WHO leaders of the project: Dr. Donald A. (D.A.) Henderson, director of the WHO’s Global Smallpox Eradication Program, and Dr. Ciro de Quadros, the charismatic and tireless WHO epidemiologist in charge of field operations in Ethiopia. These two WHO professionals not only led the successful fight to eradicate smallpox from Ethiopia, but taught the inexperienced PCVs their field craft. The book is dedicated to Henderson and de Quadros.

By 1973, smallpox, even in remote area was on the run, but Ethiopia was undergoing profound changes. A severe famine struck Ethiopia’s central highlands. A few PCVs left the smallpox project and began working in famine relief. In 1974 Emperor Haile Selassie was overthrown and an autocratic, communist-leaning government, the DERG, took power. Peace Corps withdrew from the country. WHO hung on, secured the support of the new revolutionary government and ultimately finished the smallpox project using government helicopters and highly effective Ethiopian health workers, many of whom had worked with the PCVs. In late 1979, Ethiopia — and the world — was declared smallpox free.

As for those young PCVs who had arrived in Ethiopia clutching their newly minted degrees in English and history and left the country after two years of service as battle-tested public health workers, many of them returned to the U.S. to get advanced degrees in Public Health. Some even went to work again with WHO. Michael Santarelli, the PCV who vaccinated the Mursi warriors, participated in the smallpox eradication for WHO in Bhola Island, Bangladesh, where the last recorded outbreak in Asia took place. Once a Super Vol, always a Super Vol.

•

Reviewer BARRY HILLENBRAND was a Peace Corps Volunteer from 1963–1965 in Debre Marcos, Ethiopia, where he taught history at a secondary school. As a summer Peace Corps project in 1964, he gave TB test injections in the central market in Harrar, Ethiopia. He was not required to ride a mule or to sleep in a tent, rather was billeted in a comfortable stone Peace Corps house not far from a building where, it was said, the French poet Arthur Rimbaud once lived. After Peace Corps, Hillenbrand became a correspondent for TIME magazine where he worked for 35 years. He served as Bureau Chief in Rio de Janeiro, Saigon, Bahrain, Tokyo and London. He is now retired and living in Washington, D.C.

This is a powerful story, and a tremendous effort. I will buy the book. I hope it is widely read.

Colombia Eleven, my group, was not trained to administer vaccinations, however, we worked to promote vancinations. There was a smallpox epidemic in Colombia in 1965 and the government instituted a massive vacination campaign. I have been haunted by one part of all the vaccinations programs. There was not always adequate infrastruction to sterilize needles. Sometimes, the needles were wiped with alcohol and reused, over and over. Sometimes there was a small burner with a bowl heated to boiling, in which the needles would be dipped before reuse. There were no disposable needles.

In the Ethiopia project, were there disposable needles? If not, was there any way to sterilize needles?

The Ethiopian teams did not use hypodermic needles, but a specially designed implement, the bifurcated needle, pictured above in the article. The bifurcated needle was dipped in a bottle of vaccine and a drop would stick between the forks. Then the vaccinator would jab the arm of the person and get enough vaccine into the arm. The needles cost less than a quarter of a cent apiece. So there were plenty of them. Always new and clean, although as I recall at one site so many people showed up for the vaccinations that they had to wash the needles and reuse them. But that was rare. Also one other technical advance was the use of freeze dried vaccine, thus eliminating the need to keep the vaccine refrigerated.

March 2020

Lakeport, California

Hi Joanne,

Yes, the stainless steel bifurcated needles we used were always sterilized. At the end of each day of vaccination we would seek the help of the village chief to round up enough fire wood to boil the needles for 15 minutes or more. It was always sort of funny to see the look on the village chief’s face, and those sitting around him, as they watched a non food item being boiled. They looked like they were thinking, “what a waste of perfectly good firewood.”

Michael Santarelli

I am so glad to hear that. I was not involved with mass vaccination as you all were. The LPN from the clinic, where I was assigned, would do the actual vaccination when we went out in the field to small villages. She had a Bunsen burner but the flame did not always keep the water boiling, and it was a manner of dipping the needles in the water, certainly not boiling them for fifteen minutes. She did the very best she could. I was so concerned that I discussed it with my project manager who was not medically trained. She was a social worker and told me just to tell the LPN to boil the needles. My manager had little or no knowledge of what the infrastructure available was, or interest,

Barry, Thank you so much for that information. I will read the book. It is an excellent example of how Peace Corps efforts certainly can be demonstrated successful!

This is a fascinating story I never heard before. Thanks to the authors, and thanks, Barry.

Dear Barry,

Thank you very much for writing this excellent review of our book! You’ve made the stories and the essence of the book come alive for all of us. You’re right, the guys who worked in the field were truly Super Vols, and, in my opinion, the work they did in the field was absolutely heroic!

Thanks again,

Jim Skelton

Hi, Barry– Since all this happened a few years after our service, I had only heard a hazy outline. I welcome your review and look forward to reading these heroic stories. Thanks, Mike O’Brien

Wally Runck writes,

I was an ag teacher in the Harar area in 1973-75. I had 2 friends who were smallpox volunteers and I saw first hand some of their crazy adventures. I heard some Canadian volunteers were shot at trying to do Smallpox work in the Simien mountains up north.

The military coup happened in summer or 1974 and over half of the PVCs left but I and many others stayed til summer of ’75

One more small group came in summer of 1975 but they did not stay long and then the Peace Corp were absent til 1995.

In the summer of 1974 3 of us PVCs did some drought relief for UNICEF on the Ethiopian-Somalian border. We heard stories of the Nomads vaccinating for smallpox themselves by cutting themselves and putting active puss from an infective person onto the open sore.

Wally Runck