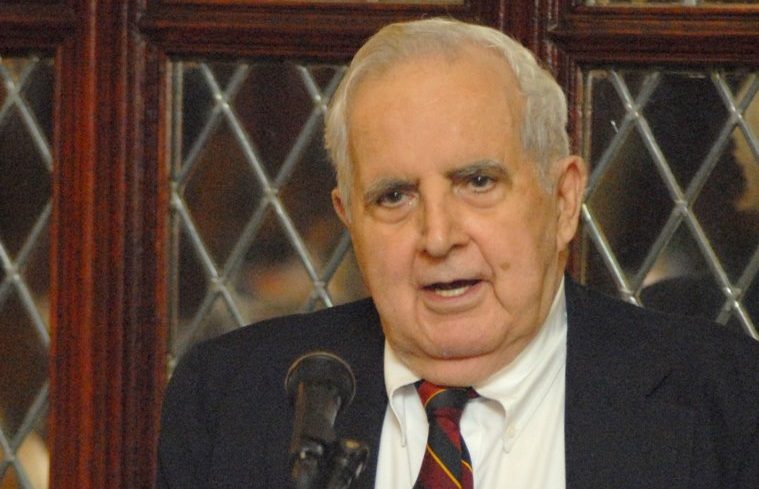

“Why Would Someone Give Me a Story Like This”? Charlie Peters

The first time I met Charlie Peters was in a job interview. It was the fall of 1999: I was 24, he was 72, and I was a candidate to be an editor at the Washington Monthly. I trudged up the stairs to the third floor of 1611 Connecticut Avenue to a well-worn office filled with old magazines and crossed by the occasional cockroach. Charlie sat across from me and a big wooden desk with a box for incoming manuscripts and one for outgoing manuscripts that he had marked up with a felt green marker. “What is your relationship like with your father?” he asked a few minutes into the conversation.

“Well,” I responded, “my father drinks way too much, but we get along great.” I didn’t realize it at the time, but the interview essentially ended right there. I was hired.

I didn’t know much about Charlie at the time. Google barely existed, and Charlie didn’t care that it did. I had only ended up there through happenstance. I was an ambitious young man flailing around trying to figure out a career. I had gotten an interview to work with an environmental group in New York City, but I showed up in a sweater and pants that didn’t fit. I probably hadn’t combed my hair. After about half an hour, the woman interviewing me declared that this wasn’t the place for me. She mused, correctly, that I probably didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life. She suggested I apply to work at the Washington Monthly. “They hire people like you.” I had never heard of the Monthly, but that afternoon I sent in a letter asking if I could apply.

A week or two later, an editor at the magazine named Robert Worth gave me a call. He didn’t have a job, he explained, but maybe I could write them a story for which they would pay 10 cents a word. A few months later, my story had run, and I was sitting across the wooden desk, inhaling the musty scent of the office and wondering why Charlie had asked me about my dad.

Charlie grew up in West Virginia and came to Washington in 1961 along with John F. Kennedy. He worked in the Peace Corps and then, in 1970, decided to found a magazine devoted to the principle that journalism could make the government work better. It could expose corruption, puncture the image of the city’s many phonies and grifters, it could reward the heroic bureaucrats who did their best inside of unheralded agencies. He wasn’t political. He wasn’t conventional. He wasn’t predictable. He loved the practice of politics but found the horse-race coverage tiresome. He had no social pretensions and scoffed at the many folks in the city who did. He didn’t care a wit about money unless he needed it to pay off a debt accrued by the Monthly.

He also wasn’t really a journalist, but he had an eye for them, as any reader of this website knows. To start the publication, he hired three young editors, all of whom would go on to have extraordinary careers: James Fallows, Taylor Branch, and Suzannah Lessard. As the years went on, he rarely faltered in the young men and women he chose. The contributors were pretty good too. Not long after I began there, we started running submissions from a brilliant upstart by the name of Ta-Nehisi Coates.

I don’t know whether Charlie had an eye for talent, or whether he nurtured it. Maybe it was a bit of both. There were usually two editors at a time, and they served two-year terms. The deal was tough: you were paid very little and worked very hard. In return, you got responsibilities you probably didn’t deserve. I was paid $12,000 a year, and I worked around 100 hours a week. I sometimes slept on the office floor, and I very rarely took weekends off. I lived with my father and learned from Charlie new ways of saving money. You should call people during lunchtime when they’re away, so they’d ring you back and save you on the phone bill. We borrowed Internet from the office downstairs when I routed an ethernet wire up the fire escape. In return for all these sacrifices, I got to edit and write stories that people with power read.

Charlie wasn’t easy. The second story I filed was about the gambling industry in Georgia and Charlie didn’t much care for it. I handed it in on a Saturday morning and was sitting in the office the next day when the phone rang. I picked it up and heard Charlie’s familiar West Virginia drawl. There was no hello or greeting. Just a rhetorical question: “Why would someone give me a story like this? Because they’re an asshole. A fucking asshole.” Then he hung up.

The next day, I sheepishly walked up Connecticut Avenue with my draft to meet Charlie at the restaurant where he was working and having lunch. I apologized for the draft and asked for clarification on what I had done wrong. The problem, he explained, was that I had written it like “a pompous dickhead.” I didn’t get much guidance beyond that. I then took the draft to Worth, who laughed at my tale and helped me fix the work. The story ran that month.

There are different ways mentors can help you improve, just as there are different ways that parents can help their children. One can be tough; one can be inscrutable; one can be kind; one can offer detailed instructions and guidance. There’s no one right approach. Now that I’ve had children and thought more about it, I’ve decided that there’s one variable that matters most: the parent, or mentor, must have genuine care or even love. And this is what made Charlie’s method work. I knew he hated the gambling story. He screamed at me more than a few times in the years to come. But I never doubted that he cared and that he wanted the best for me as well as the magazine. He cared intensely about the country; the magazine was the tool he had to help; and his young editors had to shoulder the burden of getting the darn thing out. So, I kept going, kept working, and kept trying to improve. After two years, I was unquestionably a better journalist than when I began.

I left the Monthly in 2001, right about when Charlie passed the reigns over to the wonderful Paul Glastris, a former Monthly editor who had just wrapped up his tenure as a White House speechwriter. Everyone who loved the Monthly feared that Charlie wouldn’t last long once he’d stepped away. He had lived hard and didn’t exercise much. How could he go on without the thing that, besides his family, he loved the most?

Charlie kept going though. He wrote a column for the magazine, which was like a proto-blog before blogs became a thing. He continued to mentor his former editors. When my career was going badly, he’d tell me to keep faith. When it went well, he took delight. He was charming to me, just as he’d been charming to all the people who didn’t work for him during the years running the Monthly. When my wife first met him, after months of hearing my war stories, she declared, “He’s just a big teddy bear.”

Last year, I made my final visit to his house, the same one out in Georgetown that he had moved into in 1961. I went down to the basement where Charlie sat, covered mostly in a blanket. He had made it through Covid, but he was now 95 years old and didn’t have much time left. We talked about our years together and his hopes for The Atlantic. When I left, he said something that men don’t really ever say to each other: “I love you.”

I had made plans to visit Charlie this week when I came down to Washington for the Atlantic Festival. I got news the night before my trip, though, that he had lost consciousness and wouldn’t be able to see me. He died Thanksgiving week at his home with Beth, his wife and beloved companion of 65 years. I should say it here that I loved him too.

•

Nicholas Thompson is the CEO of The Atlantic. He was formerly the editor-in-chief of WIRED. He’s also a frequent public speaker–who gives talks and moderates events around the world–and an occasional musician with three albums of instrumental acoustic guitar music. He was previously the editor of NewYorker.com, a co-founder of the multi-media publishing company the Atavist, and the author of The Hawk and the Dove: Paul Nitze, George Kennan, and the History of the Cold War.

Curmudgeons of the world unite!