WHEN CHRIST STOPPED AT EBOLI by Carlo Levi

The Story of a Year

by John Coyne (Ethiopia 1962-64)

The other weekend when visiting a small used bookstore appropriately named the “BookBarn” in rural Columbia County, New York, I spotted on a shelf of the cluttered shop a copy of Carlo Levi’s Christ Stopped at Eboli. It is a book I haven’t seen in some sixty plus years. In fact, I hadn’t seen a copy since I was a PCV in Ethiopia.

This book was one of appropriately 75 paperback books Sarge Shriver and the first administration of the Peace Corps put together in the ‘booklocker’ for Volunteers to read and leave behind in their villages as seeds for new libraries.

This book was one of appropriately 75 paperback books Sarge Shriver and the first administration of the Peace Corps put together in the ‘booklocker’ for Volunteers to read and leave behind in their villages as seeds for new libraries.

The copy I found was first published in the early Sixties. A trade paperback edition with a new preface, while the book was the same and what a body of prose it is.

First some background on Carlo Levi and Christ Stopped at Eboli for those who missed reading it when in college, in the Peace Corps, or just growing up.

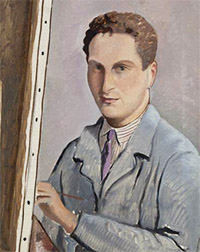

Carlo Levi was an Italian doctor and painter who had written polemics against Italy’s Fascist regime and was exiled in 1935 to Gagliano, a backward, malaria-ridden southern Italian village in Lucania.

Levi would spend a year in this village before returning to northern Italy in 1936, after he was freed with others in a general political amnesty.

The title of the book comes from an expression by the people of Gagliano who always said, “Christ stopped short of here, at Eboli” which means, in effect, that they have been bypassed by Christianity, by morality, by history itself — they had been excluded from the human experience.

Levi wrote Christ Stopped at Eboli eight years after the events he described in his book, in 1943-1944, when he was living in Florence as a hunted member of the Underground. Some months later he served as editor of a Resistance newspaper, La Nazione del Popolo and in 1945 he went to Rome and edited another Resistance newspaper and published Christ Stopped at Eboli.

Carlo Levi

self-portrait

I [and a lot of other PCVs] first read it in 1962 when we found it in our new Peace Corps book locker.

In many ways, this memoir of Gagliano is the first real “Peace Corps book.” [I will grant a case can also be made for Zorba the Greek by Nikos Kazantzakis.] In his book Levi shows an innocent outsider trying to live, and help, a peasant community. Here is this educated doctor, well known in Italian and French cultural circles as a painter, in political exile, in Lucania, thrust into a backwater, malaria-ridden southern Italian village.

As a doctor he could help, but other doctors in the region were jealous, as well as incompetent. Levi does what he could for the people and in doing so describes village life and tells their story.

He tells of futile rivalries, casual sex, ‘pig doctors,’ pompous officials, brigands, priests, and police. There are haunting tales as he tries vainly to stop the dread malaria, to care for women who came to him for medical advice in a region of Italy where, for example, the stethoscope is still unknown.

All of this is told in 25 short chapters in beautiful, quiet, unassuming prose. Here is the opening of one chapter:

It was September and the heat was giving way to promises of autumn. The wind came from a different direction; it no longer brought with it the burning breath of the desert, but had a vague smell of the sea. The fiery streaks of the sunset lingered for hours over the mountains of Calabria and the air was filled with bats and crows.”

When the word came that prisoners were to be released and he could leave Gagliano, Levi could not leave. “Everyone else left the next morning,” he wrote, “but I could not bring myself to hurry. I was sorry to leave and I found a dozen pretexts for lingering on.” The peasants, he writes, came to tell him. “Don’t go away. Stay here. Marry Concetta. They’ll make you the mayor. You must stay with us.”

“I’ll come back.” Carlo told them.

They shook their heads.

“They wanted me to make a solemn promise to return and I made it in all sincerity, but I have not yet been able to keep it.”

I am not sure Carlo Levi ever returned to the village. I am not sure it is such a bad thing not to go home again. The past is another country as L.P. Hartley wrote years ago. Tom Wolfe knew he couldn’t go home again, even to Ashville, North Carolina.

Most memories should be left unchanged. Carlo Levi was smart enough to leave his unchanged and then write about them, capturing them forever in this memoir.

Should he have married Concetta and stayed in Gagliano, this backward, malaria-ridden southern Italian village? Who is to say. Perhaps if he had, he would have written another book, but not this one, and certainly he would have produced more beautiful paintings of the people and the landscape.

Finally, as we expected, he had to leave. He went from southern Italian onto Florence and the war and his work with the Resistance. But he did not forget Gagliano. He made this godforsaken place internationally important by writing a masterpiece with the village and citizens its heroes and heroines.

What more can a writer hope to do? What more can an RPCV do but tell his or her own story?

Very well said, John. I remember the book fondly in our booklocker, and Zorba too! They seemed so real and close to our lives-not just the books, but the characters in the books. I’ve still got my Zorba, and I pick it up from time to time. And now I will find a copy of Eboli to do the same.

I read many books from that book locker that I would never have thought of reading! Books on economics, politics, geography, etc. Can’t recall the names, but I know they all served to broaden this 21-year older’s experience. I imagine now the volunteers take books along on their phones. But in 1964, that book locker was a mind-saver.

For some reason, I was never told that the books were meant to establish a library in our small, desert town. I opened the locker as if it were a personal gift from Sarge, meant to fill my plentiful spare time. I did, however, set up a library with bricks and boards in our house. A young nomad checked out a book that, by strange circuitous paths, inspired him to become a college professor in Canada. Who knows what other stories those book lockers inspired?

This is the first I’ve heard of the book locker. The Levi book sounds wonderful!

I see it was made into a film from 1979, I believe and the 4 hour series is available on the Criterion Channel.

Ah, the famed book locker!

Long gone by the time I set out for Mali 🇲🇱 in 1977, I tried to cram as many books into my suitcase despite our strict weight allowance. Then a staffer (was it you, John?) told me not to worry — that Peace Corps/Bamako had a “fine” library. So I reluctantly dumped my treasures.

Shortly after arrival, I glanced at the library room in Peace Corps/Bamako’s compound (inherited, incidentally, from North Vietnam) and was relieved to see a wall of books, messy, but inviting.

Alas! My joy at seeing the sagging shelves of books turned to horror as I moved in to read the titles. BABE WATCH, MECHANICAL ENGINEERING FOR DUMMIES, LUST IN THE DESERT, DIARRHEA DIALOGUE, TOUGH SHIT: WHERE THERE IS NO DOCTOR! and my favorite: KAMA SUTRA ON THE BRAHMAPUTRA.

My fury at the lying Peace Corps staffer was tempered over the years — as, like a prisoner, I adapted to my environment and even begged my parents to send me the latest Robert Ludlum.

PS. Were there any “good” books in PC/Mali? Ah yes, but they were hidden away in far flung posts like Dire, Gao, Kayes — and Timbuktu.

Did I visit those volunteers for their stellar, if desperate, company — or their copies of Shantaram and The Zen of Motorcycle Maintenance?

I’ll never tell.

Would you?