“What Are You?” They Ask My Son by Michael Meyer (China)

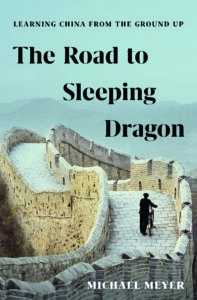

This Opinion piece appeared in The Wall Street Journal on Tuesday, October 31, 2017, written by Michael Meyer (China 1995-97). Michael teaches creative nonfiction at the University of Pittsburgh. His most recent book, just published by Bloomsbury, is The Road to Sleeping Dragon: Learning China from the Ground Up. — JC

This Opinion piece appeared in The Wall Street Journal on Tuesday, October 31, 2017, written by Michael Meyer (China 1995-97). Michael teaches creative nonfiction at the University of Pittsburgh. His most recent book, just published by Bloomsbury, is The Road to Sleeping Dragon: Learning China from the Ground Up. — JC

•

“What Are You?” They Ask My Son

At 5, he doesn’t quite understand what it means to be ‘biracial.’

‘I’m a boy,’ he says.

My son is 5. He was born in Hong Kong and spent the past two years in Singapore. We returned to the U.S. so he could grow up here, and the culture shock has been minimal: Like his fellow kindergartners, Benji loves Legos and belting out “Let it Go.” Unlike them, he plays piano, which he learned in a Singapore preschool. Also unlike them, Benji is constantly asked: “What are you?”

It’s a weighty question for an adult, but to a child it sounds silly. “I’m a boy,” Benji replies. Sometimes he decides he’s a girl. But this isn’t that story, this is about being a biracial kid in America.

In Singapore, Benji was simply a foreigner, just like mom (born in Manchuria) and dad (born in Los Angeles). Although China is as much of a melting pot as America — with 56 ethnic groups and 150 languages — it does not hyphenate identity. You are Chinese first, and then Han, not Han-Chinese, or Tibetan-Chinese, or Manchu-Chinese.

In China aunties extol Benji’s handsomeness and call him hunxue’r, “mixed blood.”

Having learned sarcasm in America, Benji once answered: “Actually, I’m a dog.” The person then asked me about his breed.

On playgrounds, well-intentioned American yoga moms riff on Benetton ads and extol his appearance as if it were a decor choice. These conversations surprise me: I went to college in the early 1990s, and was taught never to talk about race or ethnicity. Today Americans seem to think it’s impolite not to. With benevolent curiosity, they ask: “What’s your son? Is he a half?”

We have to decide, for school and doctor intake forms request a child’s identity. We don’t consider Benji half of anything. He’s more than the sum of his parts, fluent in Mandarin and English, along with some Hebrew, learned at a Jewish summer camp, although neither my wife nor I am Jewish.

When pressed, we say he’s a “double”— as the Japanese put it, daduru. Being a double sounds lucky. You get not one, but two cultures.

“Double” also invokes intrigue. Being “mixed” carries the historical connotations of impurity, of illegality. Not until 1967 did the Supreme Court rule interracial marriage constitutionally protected.

Although a 1993 Time cover declared a multiracial composite “The New Face of America,” the American census didn’t allow people to choose more than one race until 2000; in 2010, nine million respondents marked multiple boxes. That seems like a statistical outlier in a population of 326 million, but a 2015 Pew Research Center report called multiracial Americans “young, proud, tolerant and growing at a rate three times as fast as the population as a whole.”

The majority of those surveyed had been targets of racial slurs and jokes. So I tense up when people ask me what Benji is. But kids are smart. On his own, Benji has decided how to answer people, anywhere in the world, who ask him what he is. He says with finality: “I am an American.”

” I am an American” says it all! For me that includes all of us in North America, Central America, and South America.

Beverly Hammons, RPCV Ecuador