Washington Post review and comments on Larry Leamer’s (Nepal) book MAR-A-LAGO

Thanks to the ‘heads up’ from Dick Lipez (Ethiopia 1962-64)

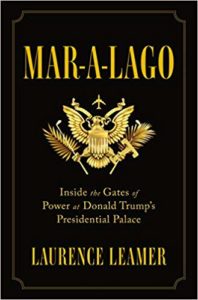

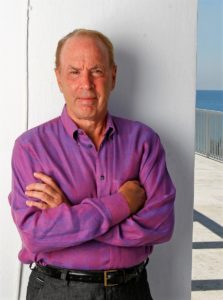

Article and review of Laurence Leamer’s (Nepal 1965-67) Mar-a-Lago: Inside the Gates of Power at Donald Trump’s Presidential Palace.

•

How Mar-a-Lago’s denizens nurtured Donald Trump’s ego

How Mar-a-Lago’s denizens nurtured Donald Trump’s ego

By Robin Givhan

Washington Post

February 7

Palm Beach is a horrible place. According to Laurence Leamer “Mar-a-Lago: Inside the Gates of Power at Donald Trump’s Presidential Palace,” the Florida enclave is populated by snooty old-timers and egotistical arrivistes, social climbers and brown-nosers — all of whom are willing to tolerate and even reward the most egregious behavior if it means basking in the nuclear glow of the latest buzzy power player. It’s a town where wealthy husbands fight petty battles in court and middle-aged wives fight wrinkles and weight gain as if their marriages depend on it, because they so often do. It’s a wretched village filled with grotesque anti-Semitism and casual racism, but with striking ocean views.

“Those who lived north of Sloan’s Curve, where the condominiums began, referred to the area derisively as ‘the Gaza Strip,’ ” writes Leamer. “If some Americans condemned Palm Beach as a place of institutionalized anti-Semitism, that was a small price to pay not to have dinner in the same room with ‘them.’ ”

At the epicenter of it all sits Mar-a-Lago, a black hole of pomposity and insecurity. To understand how Trump fits into his adopted winter home is to understand how he operates in the world at large, Leamer promises; this relationship can supposedly explain the psyche of the 45th president.

But this book is less about the interior life of Trump and more about the excesses and neuroses of his fellow villagers — the ones who have nurtured his ego and facilitated his grip on power. No one comes out looking good in “Mar-a-Lago,” not even the book’s author.

Leamer opens with a note to readers explaining that he and his wife purchased their home in Palm Beach in 1994, the same year Trump transformed Mar-a-Lago into a private club. This revelation is followed by a disclaimer, of sorts. Leamer is not a member of Mar-a-Lago, but he has friends who belong, so he has often played tennis on the club’s courts and dined in its restaurant. For the book, Leamer interviewed club members and witnessed firsthand some of the scenes he recounts. He did not sit down with Trump.

In the early pages, one almost feels sorry for Trump. When the ostentatious businessman arrived in Palm Beach — before he tangled with the Town Council and the Preservation Foundation, before he transformed Mar-a-Lago from a private estate into a private club, and before he upended long-standing traditions — he hosted a dinner party for the denizens of its entrenched old society. As waiters were serving coffee, Trump suggested going around the table so each person could say a little about who they were and what they did. The guests responded as if he’d just asked them to hand over their financial records.

“One of the grandes dames rose slowly and stood quietly as she looked across the table. ‘I live in Palm Beach,’ she said finally. ‘And I do nothing.’ With that she sat down while the other guests contemplated her words. Another of the ladies, copying the first lady’s words, rose and said, ‘I live in Palm Beach. And I do nothing.’ Trump had merely been trying to enliven the island’s tired social rituals, but he discovered that most of these people did little. That was the point. They didn’t have to do anything. They stayed among their kind.” And their kind, apparently, are fairly self-absorbed and dismissive.

From the beginning, Palm Beach disliked Trump. He was quietly advised not to bother applying for membership at the fancy clubs in town, to avoid the humiliation of an inevitable rejection: He was too flashy. His money was too new. His blood wasn’t blue enough. Residents’ disdain only grew once Mar-a-Lago became a club — at least that’s the picture Leamer paints. Yet as Trump coated Mar-a-Lago with a high gloss and filled it with celebrities, the residents began to tolerate Trump and even flatter him because it was to their benefit. What rewards did they accrue for holding their noses? Mostly, they were able to retain their expensive memberships at Mar-a-Lago and continue socializing with a cast of wealthy hypocrites, some of whom seem just as insufferable and shady as the man they judged so harshly.

Occasionally club members could no longer stomach Trump’s insults or his insistence on being the sun around which Mar-a-Lago revolved. They fled. But Trump would refuse to return the membership fees to which they were entitled. When one departing member, a local jeweler, tried to publicly shame Trump by taking out an ad in the town’s paper and attempting to form a posse of other disgruntled members, he didn’t get very far. “Nothing ever came of it,” Leamer writes, “in part because five months later the jeweler was charged with grand theft and fled the island.”

In 1993, in an effort to rankle old society, Trump hosted a bachelor ball at Mar-a-Lago on the same night as the International Red Cross Ball, which was considered the height of the town’s social season and one of its most important charitable events. Charity, however, was no match for sports stars and pretty women.

Trump invited “pro football and basketball players, many of them black, busloads of models, Miami Dolphins cheerleaders, a smattering of the usual social suspects, along with scores of reporters and paparazzi. Not invited were the gentlemen sitting at the bar next door at the Bath and Tennis Club having a few stiff ones before heading over to the Red Cross Ball at the Breakers. They could condemn Trump’s garish vulgarity all they wanted, but what man didn’t want to be at the Bachelor Ball?”

Leamer offers spicy anecdotes that underscore well-reported aspects of Trump’s personality: his boasting about personal charitable donations that don’t exist, his blithe refusal to pay his bills in full, his weaponization of lawsuits. If you’ve been even a cursory consumer of news, none of this will be jarring.

What does stop a reader are Leamer’s assessments of residents, particularly women. Perhaps his descriptions are meant to reflect the collective mind-set of Palm Beach — of which he is, at least, a part-time member. Perhaps they are meant to read as if uttered by Trump himself. Perhaps, perhaps, perhaps. Nonetheless, the descriptions are written from the perspective of the narrator. They are in Leamer’s voice, and he assigns the women in Trump’s life value based on their appearance.

On first wife Ivana Trump: “Ivana had done everything — the executive jobs, the effort to stay thin, the work on her face — largely to hold on to her husband, but none of it mattered. Trump needed to come strutting into a room with a woman on his arm whom every man desired, not meandering in latched to a woman approaching middle age with the body of a mother who had thrice given birth and the droning voice of a bossy businesswoman.”

On second wife Marla Maples: “Trump may not have been able to laugh at himself, but his life was going great again. He had a new wife and baby. Marla had slimmed down and was the same sexy honey who had driven him half crazy.”

There is, by now, an entire subcategory of political nonfiction devoted to Trump. “Mar-a-Lago” doesn’t enlighten readers on Trump as a businessman or a politician. Instead, it shines a light on the craven culture he exploited, where the media, the business community and the local government all went giddy and stupid at the thought of fame. On New Year’s Eve in 1999, TV networks sent cameras to Mar-a-Lago to get Trump’s comments on the new century — not because he was especially eloquent or thoughtful, but because he was famous. Small-business owners extended credit to Trump despite his well-known reputation for not paying his bills — after all, he looked wealthy. The Palm Beach Town Council and other village regulators caved to Trump’s demands to build a grand ballroom at Mar-a-Lago, to install an enormous flagpole and to claim a sketchy tax deduction because he threatened lawsuits, temper tantrums and public insults. Oh, and because he was famous. Trump was able to make Mar-a-Lago a success in part because of the island’s entrenched anti-Semitism and racism. The club attracted Jewish members — as well as the nouveau riche — who were denied membership elsewhere. Trump was able to leverage a preexisting us-vs.-them mentality to his benefit.

Mar-a-Lago members bore his insults and jibes because being in the vicinity of fame inflated their own egos. “It was Richie Rich playing with all his toys,” said one charter member. “Donald was under the gun to make everything first class, and that’s what he did. We’d say, ‘Holy cow, look who Donald has coming!’ For $120 you had a fabulous buffet dinner and a show with a fifty-piece orchestra and a world-class performer like James Brown or the Temptations. Many of the performers stayed around and you could talk to them just like anybody. I had lunch with Tony Bennett once and played tennis with Regis Philbin.”

The message from Leamer’s book is this: Sure, Trump may be selfish, rude and a liar. But this horrible human was not grown in a test tube. He was, Leamer argues, nurtured, coddled and propped up by the equally despicable humans of Palm Beach.

•

Robin Givhan is a staff writer and The Washington Post’s fashion critic, covering fashion as a business, as a cultural institution and as pure pleasure. A 2006 Pulitzer Prize winner for criticism, Givhan has also worked at Newsweek/Daily Beast, Vogue magazine and the Detroit Free Press.

Sir Richard Branson’s private island, Necker Credit: Alpha … based upon my personal experiences with Donald Trump, … 08 Feb 2019, 5:45am