Volunteers to America: The Reverse Peace Corps

by Neil Boyer (Ethiopia 1962-64)

April 18, 2021

•

After I returned from Ethiopia, where I had served in the Peace Corps from 1962 to 1964, I went to work at Peace Corps headquarters on Lafayette Square in Washington. Harris Wofford had recruited some former volunteers in Ethiopia and other places to work with him on his seemingly limitless ideas.

I helped him and others flesh out the idea of creating a “reverse peace corps” that would bring teachers and social workers from other countries to work in the United States. It was exactly a reverse of the Peace Corps concept, with volunteers selected by sending countries and supervised and administered by receiving agencies in the United States.

Argentina would choose and send volunteers, for example, and US officials in OEO, the Department of Education and private agencies would supervise them. The program was called Volunteers TO America (VTA). (The name was often confused with the charity called Volunteers OF America.)

It was a somewhat controversial idea and faced resistance, but Harris aimed high and eventually worked it out with very senior people in the government, including Douglass Cater, Special Assistant to President Lyndon Johnson; Charles Frankel, Assistant Secretary of State for Educational and Cultural Affairs; Harold (Doc) Howe, the US Commissioner of Education; as well as senior officers of the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO), and the State Department’s Bureau of International Organization Affairs (IO) . Key players in the Congress were brought along to support the developments.

The program was essentially created within the Peace Corps, later established in the Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (CU) and then moved to its Bureau of International Organization affairs. To make it work, at the start, I was transferred from the Peace Corps to CU.

Much has been written about the history of the VTA program, including master’s theses and many press reports. I wrote articles and memoirs about the experience. There were many positive results. The program was small, but it ran for three years under my supervision in CU.

The Argentine volunteers who were ready to come to America in 1967. Some of my colleagues at the State Department suggested this was “Neil Boyer’s harem.”

Supervision

Besides my dealing with the program from the State Department, we had contracts with other agencies to manage the details:

- The School of Education at the University of Southern California handled the teaching volunteers in the western part of the country. Individuals involved were Dean Irving Melbo and John Carpenter in the School of Education. Barbara Wilder (Hodgdon) was the direct liaison with the volunteers.

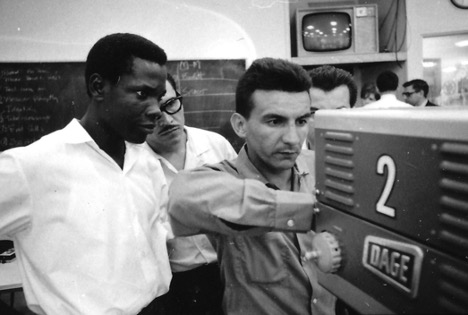

Training to appear on television: Argentine volunteers Emma Bonfils and Darma Valentini

More volunteers: Ben Mbroh, German Rubio, Hector Pulido

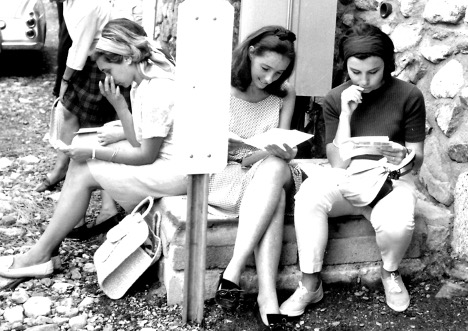

Lonely volunteers get news from home: Emma Bonfils, Margarita Giraldo, Ana Bobek Caceres

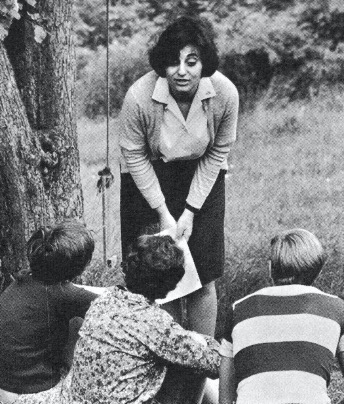

Maria Gagliardo of Argentina with young students

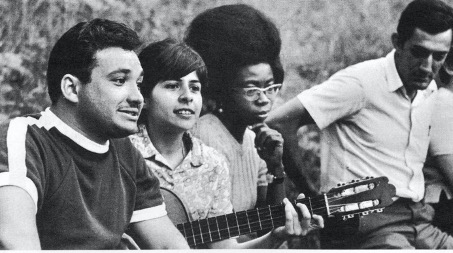

Learning U.S. folk songs: Volunteers from Venezuela, Argentina, Ghana, Iran

- The Experiment in International Living, based in Putney, Vermont, handled volunteers who would teach in schools in the East. Gordon Boyce was then president of the Experiment and I stayed overnight in his house when I visited the first group of volunteers. Other staff involved were Jack Wallace, EIL vice president, and Max Benne, who managed contact with the volunteers from his home in Michigan.

- The Commonwealth Service Corps (CSC) in Massachusetts, together with staff of VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America), handled the volunteers in social work and community action situations. VISTA was part of the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO), the government’s anti-poverty program, and had many volunteers of its own.

- Some of the Volunteers to America were assigned as VISTA volunteers, such as those on a Cherokee Indian Reservation in North Carolina, and those in East Harlem, New York City. (This was a complicated and often misunderstood arrangement. An individual could be both a VTA and a VISTA volunteer, but it produced some outstanding VTA results.)

- Staff involved were John Cimarosa at CSC and Jeff Binda at VISTA. A number of volunteers from this group were featured and photographed in VTA brochures and magazine articles. See the brochures at American University.

- I probably contributed to the complications by my hands-on management. I would take opportunities to talk directly with the volunteers by phone or in occasional meetings, thereby leaping over the contractors in some instances. I would guess I was sometimes a pain to them.

- I knew most of the volunteers personally. It was a complicated arrangement, but we thought it necessary to get attention and support for the Volunteers to America at the local level and to prepare for the larger numbers of volunteers we hoped for in future groups.

Operations and Administrative Issues

The program worked well in most instances. On the education side, there were some local supervisors or school officials who did not know how to utilize the volunteers well. A few told them simply to prepare a presentation about their own countries and to deliver it to each class.

That worked well for one or two classes, but the volunteers could not continue to give the same 50-minute lecture multiple times a day from one day to the next. They would be bored and not challenged to innovate.

John Carpenter, head of the USC School of International Education, explains a teaching concept to Volunteer Margarita Giraldo.

The USC staff developed a program in which, for example, four volunteers from different countries would each give a presentation to the same class about politics in their country, or about music, or courtship, or sports – one day at a time. And then on the fifth day, they would discuss the same subject as it related to the United States and then compare the experiences.

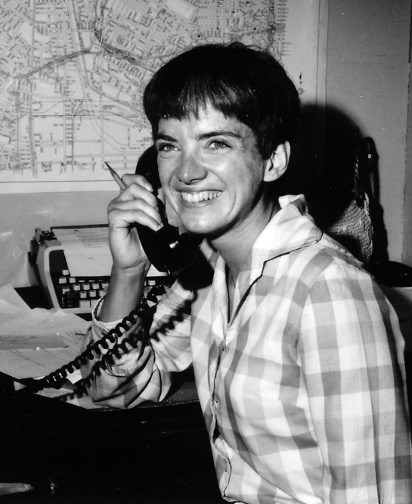

Barbara Wilder Hodgdon (Malawi 1962-64) at USC was the key coordinator for the volunteers west of the Mississippi

This exercise in comparative education worked well and was well appreciated. I later prepared a “handbook for local supervisors,” in which I described this and other techniques for utilizing and managing the volunteers. (In an example of my problems with State Department bureaucrats, the designation of money for the handbook was denied and the project was never completed.)

Discussing the training over lunch: Dean Melbo and John Carpenter of USC with program director Neil Boyer (center)

Problems with Volunteers

Volunteers in general got along well with each other and with their hosts. However, there was one volunteer who seemed to follow the philosophy that rules are made to be broken. He would disappear from his home community unannounced, import relatives from his home country, sometimes be suspected of responsibility for missing property. He was a difficult discipline issue for his supervisors.

On his first day in America, he was placed in the home of a young couple who were interested in being hosts in an exciting new program. The next day, the husband went to work, leaving his wife alone with this contentious volunteer. That night, the couple asked that the volunteer be moved somewhere else. He was trouble.

Similarly, another young woman offered to take this same volunteer to a hospital for treatment of a difficult skin problem, and he made inappropriate advances to her in the car on the way to the hospital. Facts are not clear, but I believe he was sent home. Enough is enough.

Also, in the early assignment stages, one volunteer from central America refused to work with an Asian volunteer. Why not? She pointed to her eyes and pulled them to the side to make them slanted. She couldn’t deal with an oriental person. No, we said, that’s not acceptable. One of the reasons for this program is that we seek to overcome such prejudices, and we work together.

In another instance, two male and two female volunteers were placed in the same lodging in different rooms. One of each was from the same country, and they did not know each other before arriving in America. They got acquainted, perhaps too well, and soon their amorous adventures became very noisy. They disturbed the uninvolved male of the group, who said he could not sleep for all the racket and asked for a transfer to somewhere else. A new place was found for him.

The only death in the program occurred when one volunteer hung himself in the attic of the home of his host family. It was a shock to the school and the program and his embassy. There had been indications that the volunteer was depressed or had other health problems, but no one, not even the physician and psychiatrist who saw him, took action to get him the help he needed.

Besides the shock of the death, the local supervisor seemed more concerned about recovery of his slide projector, which the volunteer was using in his classroom presentations. The supervisor was afraid the authorities would confiscate his school property when investigating the death.

I unintentionally contributed to an incident by popping into a school where a volunteer had been assigned. I liked to visit volunteers if I was in the neighborhood where they worked. I went to the school, went through a side door, and asked students in the hallway where I could find the volunteer. I found her and we had a constructive conversation.

But I wasn’t thinking. An officer of the Department of State doesn’t just pop into a local school to do that without first checking with the principal or school superintendent, or without at least stopping at the front desk. Advance notice would have been good publicity for VTA and even the school system, which was benefiting from a national program. It turned out that afterward the school was upset and the girl was upset by my visit, and I had a lot of repair work to do. I wouldn’t do that again.

One day I had a call from the local supervisor of a volunteer on the West Coast. He understood that the girl was soon to be transferred to another site, but he didn’t know why, or when, or where, or any other details. He was very upset and accused me of mismanagement. Our conversation didn’t satisfy him, and he demanded to talk to my supervisor.

The fact was that I was very much a free spirit with many aspects of this program. I really didn’t have a supervisor who understood what was going on, and I liked it that way. But he insisted on the name of a superior, and so I told him I reported to Dean Rusk. That was, in a sense, true, but ludicrous, and he quickly figured that out. There was no way he could use the phone to dig through the government bureaucracy to talk to the Secretary of State to complain about me. He dropped it.

After final transfer of the program back to the Peace Corps, the program was terminated because of some negative, insular attitudes in the US Congress. One Congressman inappropriately said we have enough communist social workers in the United States, and don’t need to import them. Congress then prohibited the expenditure of any more funds for the program, and that was the end.

For those interested in more details, a large collection of documents from the Volunteers for America (VTA) program is deposited in the Peace Corps Community Archive, American University Library, Washington D.C.

Conferences

We held mid-term conferences so that the volunteers and staff could reflect on what they had done and consider changes that should be made in the future. Teachers in the East met in Vermont, those in the West met on the Idyllwild campus of USC in the mountains of southern California, and the community development volunteers went to New Orleans, as arranged by VISTA staff. Very constructive conversations were held in each place, and I attended all of them.

In New Orleans, Jeff Binda arranged for a special speaker. He was a member of Congress from Illinois, Donald Rumsfeld, who later became the director of OEO and then Secretary of Defense. He was a good politician and happily posed for photos with the volunteers. Most of them didn’t know who he was but thought he must have been someone important.

In addition to these reviews, the State Department worried about how complex and how large this program would grow to be, given the initial high-level administration interest in the program. Harris Wofford was initially thinking in terms of thousands of foreign volunteers.

Bob Klaber, an analyst from the department’s management staff, was assigned to do a detailed evaluation of the program, and he was very thorough. He spent a lot of time with me and other supervisors and visited several volunteer sites. In the end, we had Klaber’s evaluation for State and a separate USC evaluation on the education side. The program was thoroughly studied, probably far beyond its cost and scope. The conclusions were very positive. Copies of the studies are included in the documentation at American University.

Conference at the White House

At the end of the first year of the program, in July 1968, we brought all of the volunteers and staff to Washington for a terminal conference to review what they had accomplished and to think about the future. Many of the first group of volunteers would be going home after the conference.

In celebration, I arranged for the group to take a boat tour from Washington to Mount Vernon. When we got to visit the White House, we had a group picture taken on the front steps of the building, a good souvenir for everyone.

Volunteers at the White House

Inside, we sat at a large table in the Roosevelt Room, and Douglass Cater, Special Assistant to the President, spoke with the volunteers and took questions.

I was disappointed with some of the questions. Many of the streets of Washington had erupted in riots just a few months earlier. Martin Luther King had been murdered on April 4, 1968. There was plenty to talk about. But the first volunteer to raise his hand pointed to Frederic Remington’s bronze sculpture of the bronco buster on a nearby table and asked only if President Johnson was a cowboy like that.

Moving to the State Department

When I moved to the Department of State, a position (and desk) had been set up for me within the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, known in the bureaucracy as CU. While working with the selective service commission, I could walk to the White House from my home in downtown Washington. After joining State, my travel was more complicated and involved the Washington Metro and sometimes a bus.

My first day on the new job at State was New Year’s Day, January 1, 1979, when I met with David Schimmel at his home in suburban Maryland. David had worked with Harris Wofford and me at the Peace Corps as the reverse peace corps program was discussed. He briefed me on developments thus far, including exploratory initiatives with other countries that sought to determine if they would be interested in sending volunteers for this new program.

David handed me a pile of paper related to the program and warned me about the negative feelings for the program within the lower-level State Department bureaucracy. He then left for an academic position, leaving me alone. He said good luck.

I had a desk within the suite of offices occupied by Assistant Secretary of State Charles Frankel. It was a small office, but it impressed visitors who saw that I was being given high-level attention. I shared a secretary with other officers in the same suite. As it turned out, one of the secretaries who helped me out was Suzanne Shields, the girlfriend (and later wife) of my cousin David T. Boyer from Easton, Pennsylvania (small world). She still remembers.

Note: Charles Frankel had been a distinguished professor of philosophy at Columbia University. He resigned from that position in 1967 in protest of the Vietnam War. He and his wife were fatally shot during a robbery in their New York apartment in 1979.

As Dave Schimmel had warned me, long-time bureaucrats in the cultural exchange business had their own ways of operating, and they were not too enamored of this interloper from the Peace Corps who had been plopped down in their midst. Except for a very few people, they were not going to cooperate with me, despite the high-powered push behind my assignment.

My chief duty was to develop the concept of the reverse peace corps that I had worked on briefly before moving to the study of the Selective Service Commission. I did not need to be, or want to be, prompted by State Department staff on what actions to take. I knew what I was doing. My real task was to resist the pressures from long-timers in State to do it the old way. I basically ran the program for the next three years.

At the beginning, I was on loan from the Peace Corps to State. In the end, the State Department transferred the program back to the Peace Corps. Normally, when two agencies undertake an important administrative reassignment, such as this, briefing papers are prepared for the principals to meet and reach agreement.

In this case, I was the key person who had worked on all aspects of the program and so I prepared the briefing papers for both sides: Elliott Richardson, the Deputy Secretary of State, who got the approval of William Rogers, the Secretary of State, and Jack Hood Vaughn, the Director of the Peace Corps.

There had been many discussions and informal agreements between the agencies before this event. The papers arranged for State to offer to transfer the program to the Peace Corps and for the Peace Corps to agree to receive it. I wrote the papers for both sides. I did not attend the meeting, but the plan worked.

The program moved and I took up my new position as a staff member of the Peace Corps. Joe Blatchford shortly thereafter became the new director of the Peace Corps, and Kevin Lowther took over as administrator of the VTA. I gave the files of the program to Kevin and left the State Department on January 23, 1970, almost exactly three years from when I took over the program, on January 1, 1967.

•

Neil Boyer (Ethiopia 1962-64) taught at the Commercial School in Addis Ababa and at Haile Selassie University. After his tour, he was appointed the first director of the “reverse Peace Corps,” called Volunteers to America, then worked in the International Organizations bureau of the Department of State for most of the next 40 years. Retired, he is married to Johanna Misey Boyer and lives in Silver Springs, Maryland.

Neil, WOW and WOW! I enjoyed the tale. Bill Ethiopia 62-64.

Not “tale” a very interesting and life changing historical event for all involved

Your tale brings back memories of another worthwhile program that was a victim of the Vietnam war budget crunch: the International Education Act of 1966. When I returned from PC/Ethiopia, I joined the staff of John Gardner’s Dept. of HEW. Joe Coleman, one of the early PC leaders, led me to the office of the Assistant Secretary for Education, Paul Miller, former President of the University of W.VA., where I became Assistant to the Assistant Secretary for Education. Friends thought I must have been the worst typist and filer in the history of the Republic. Our task was to plan the implementation of LBJ’s International Education ACT. Principals helping in the process included Cater, Frankel, and Howe. With such a cast involved, the planning was excellent, but Congress gave no money to involve the U.S. Government in improving Americans’ knowledge of other peoples and places. The program faded away with the end of LBJ’s term. For details, see my book “International Education” (Praeger: 1994).

I had heard of this program, but never the details. Fascinating. The rumor was also of a Senator who denied funding because he didn’t want foreigners telling us what we should be doing!

I was involved with a similar program created by Latin American countries to set up a Peace Corps style program within the region. In my case, about 15 volunteers from various Latin American countries were brought to the Dominican Republic to work in rural settlements with the Dominican Agrarian Institute (IAD) where I was assigned as a Peace Corps Volunteer. It failed mostly because some of the volunteers engaged in local political protests!

Hello Neil,

So nice to read about the program I took part in. Living in a small rural community in North Carolina was an enriching experience for me. I was one of the VTA Vista volunteers – I don’t remember this double affiliation as being problematic.

Tamar Dothan, israel

I los spent few months of VTA with VISTA MINORITY MOVILIZATION In An Tonio tx

I los spent few months of VTA with VISTA MINORITY MOVILIZATION In SAn Antonio tx