To Die On Kilimanjaro by John Coyne (Ethiopia)

I posted an earlier version of this essay on this site in 1997

To Die On Kilimanjaro

When I first visited the Blue Marlin Hotel in Malindi, Kenya, in the summer of 1963, it was after my first year of teaching at a PCV in Addis Ababa. The hotel was located on the edge of the Indian Ocean and crowded with British families in the final days before Kenya’s independence from Great Britain. We were the only Americans in the hotel.

I didn’t return to Kenya or the Blue Marlin until the early ’70s when the hotel was now filled with German tourists and the few English-speaking tourists gravitated to one end of the bar. It was there traveling through Africa and writing for Dispatch News when I met a British couple and their two little girls.

Phillip and April were ‘on holiday’ as the English like to say. Phillip was a secondary school teacher in Botswana, a country I had been to a few months earlier. In fact, I had been to Maun where they lived and where he taught in a secondary school.

Phillip, I was to learn, also had returned to Malindi and the Blue Marlin (like me) for sentimental reasons, but his memories were quite different from mine, and he did not speak of them until April took her children off to bed and Phillip stepped over to where I was sitting at the bar and sat beside me.

The ocean was just fifty yards. Across the sandy beach we could see the whitecaps sparkling in the moonlight. The Small Rains were over so we moved from the bar to chairs on the sand terrace and continued to talk about living in Africa.Now we were removed from the noise of the bar. We were alone under the vastness of a bright starry night. One cannot imagine how many stars there are in the heavens at night until they have sat out under an African sky.

The ocean was just fifty yards. Across the sandy beach we could see the whitecaps sparkling in the moonlight. The Small Rains were over so we moved from the bar to chairs on the sand terrace and continued to talk about living in Africa.Now we were removed from the noise of the bar. We were alone under the vastness of a bright starry night. One cannot imagine how many stars there are in the heavens at night until they have sat out under an African sky.

Phillip mentioned that his parents had been teachers, too, but in Arusha, Tanzania when he was a university student at Oxford. He told me how he would come out on holidays from England to visit his family.

Phillip was only a few years older than me, in his early thirties, and he was handsome in that correct English upper-class way. His wife April was stunningly beautiful, blond and elegant in that graceful way of those women we saw on the Downton Abbey show.

I asked Phillip if he had ever climbed Kilimanjaro, and he shook his head and fell silent. He took out a cigarette and lit it. He sipped on his Tusker beer and didn’t say anything for a moment. I thought at first, I must have touched on a raw topic. And then I realized he had something to tell me, to tell a stranger he had met by chance and would never see again. And he said next, in the quiet and proper calm way of the English, that he knew someone who had been killed on Kilimanjaro.

And this is the story he told me that long ago night on the beach of the Blue Marlin Hotel in Malindi, Kenya under a bright and starry African sky.

*****

Phillip was nineteen when he went to Arusha after his first year at Oxford. He was “down from Oxford and out in Africa” for the long holiday to see his parents who had recently left England.

Phillip was nineteen when he went to Arusha after his first year at Oxford. He was “down from Oxford and out in Africa” for the long holiday to see his parents who had recently left England.

It was in Arusha where Phillip met Arthur, the school’s sports instructor and his wife, Gina.

Arthur was active and outgoing, warm and friendly. “One of those ‘life of the party’ types I couldn’t stand at the time. I was a bit of snob, thinking of myself a scholar because I was reading history at Oxford.”

Arthur, Phillip recalled, was “always kicking around a football or looking for someone to play a game of tennis with.”

Gina was different. She was twenty-six or seven, older by a few years than her husband, older by almost a decade than Phillip. She was a woman, Phillip said, “who watched and waited.”

From the very first sight of Gina on the lawns of the school, Phillip was smitten. It was a Sunday afternoon end-of-school party for the faculty and staff and he was being pranced about and introduced by his father to the faculty.

It was an afternoon event for women, Phillip said, to dress “to the nines.” But it was also sad because their clothes was out of date and style. They had come to Africa to teach abroad and time and fashion had passed them by, living as they were in this outpost of the world. The women were dressed in flowered dresses and wearing big hats, all white and pasty as the African houseboys moved among them carrying trays of food and drinks. They were sad, dull and old. All but Gina.

Gina was dark and Mediterranean. She was quiet and shy, Phillip said, “with black olive eyes.” And when she was introduced to him by his mother, “Oh, Gina, dear, meet my son; he’s out from Oxford.”

Gina stared at him without speaking. Later she would confess she had been mesmerized by his looks. That was the word she used, ‘mesmerized,’ Phillip said, “I never forgot that, but who would forget having this dark haired, dark eyed beauty say they were mesmerized by you, when you were only a lad yourself?”

Phillip broke off his story then and stood abruptly and asked if I wanted another round. He was buying. I noticed that with the telling of his tale, he had become more outgoing, expansive. Of course, it also meant that he had had too much to drink. When he returned with my lager, I saw he had switched drinks and had a brandy and soda in his fist.

He never left Gina’s side all that Sunday afternoon, he recounted, nor did she to want to leave him, it appeared. He was full of news and stories and gossip from London. She was from London, she told him, born there, but her parents were Italian. Her father was a “green grocer” and she was working at a shop girl in Harrods when she met her future husband.

Arthur was just out of technical college and he swept her off her feet by saying he would take her to Africa. She would do anything to get away from Harrods and England and her family, and when she stepped off the plane in Dar, she fell in love with Africa at the first sight.

For the next several days after meeting at the faculty party, Phillip and Gina were inseparable, meeting up by chance and design at shops and bars in town. His ‘Mum,’ was concerned from the very first at the sudden intenseness of his interest in Gina. She had seen them at her party, standing alone under the giant Baobabs tree in the back lawn the whole of that African afternoon.

He was endlessly curious about Gina, peppering his mother with questions. Of course, his mother was aware of how unhappy Gina was in Arusha, and only in the second year of her marriage. Gina did not have a proper job, or children to care for, or any interest that would blend her into the English community. She did not play sports. She did not play cards. She was only happy, her mother told him, when she was reading. “She read all of Jane Austen,” Phillip told me, “during the Rainy Season in Tanzania.”

He knew other faculty wives were aware of his interest in Gina that summer. They teased him when they could. It was all “quite charming really,” he said, “But for the most part, the wives and their husbands were packing up and heading back to England, as they put it, ’for a bit of civilization.’ Arthur and Gina were also going home for the long holiday.

There was nothing physical about Gina and Phillips friendship. They found in each other the warmth they didn’t have in their own home. He was estranged from his family as a headstrong teenager, having grown up apart from them through his adolescence. She was not deeply in love with her husband, nor did he really love her.

“He married me,” Gina summed up, ‘because he was afraid to go to Africa alone.”

Then one afternoon when Gina and Phillip were at the English club having lunch on the quiet cool and empty terrace, Arthur found them and rushing in great haste and excitement said “straight away to me” Phillip said, “that he was planning a climb up Kilimanjaro and did I want to go with him?”

Phillip had, in fact, come out to Africa that summer with plans to climb Kilimanjaro. Here was his chance. Arthur had made all the arrangements. It would take two weeks. A day or two to get from Arusha to the base of the mountain, then seven days up and two days down. The climb was really nothing much more than a long walk through four ecosystems, going from the forest zone, to the heather zone, then alpine desert and finally the ice cap.

Phillip had, in fact, come out to Africa that summer with plans to climb Kilimanjaro. Here was his chance. Arthur had made all the arrangements. It would take two weeks. A day or two to get from Arusha to the base of the mountain, then seven days up and two days down. The climb was really nothing much more than a long walk through four ecosystems, going from the forest zone, to the heather zone, then alpine desert and finally the ice cap.

In the late fifties there weren’t wonderful organized tours that are in place today where small armies of Tanzanians are employed as porters to carry chairs, tents, water, sleeping bags, and even chemical toilets to reach the 19,340 summit of Kilimanjaro.

Arthur was rushing to organize the trip, he told Phillip, and he would be leaving in a day or two. With that, he planted a hasty kiss on Gina’s cheek and was off, like a schoolboy free from class.

On the terrace of the English club, Phillip and Gina sat in silence in the wake of Arthur’s swift arrival and departure. At first, Phillip thought Gina might be feeling guilty that her husband had found her having lunch with another man, but then Gina turned to him and said with some urgency, “Don’t climb Kilimanjaro. Don’t leave me.”

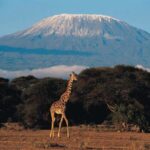

Around 750,000 years ago, give or take a few centuries, an apocalyptic explosion along one of East Africa’s many fault lines, vomited up lava and fire for thousands of years, giving birth to the first of Kilimanjaro three separate but closely aligned peaks. Shira, the mountain’s first volcanic cone, eventually collapsed. Mawenzi arose soon after, and then went dormant. Forty thousand years later came the last and most famous cone, Kibo.

Kibo holds the summit and its famed and imperiled snows. The first non-Africans to see Kilimanjaro were most likely Arabs who traveled the continent’s caravan route in the sixth century C.E. However, Ptolemy wrote of a ’snow mountain’ around 100 C.E. The next known reference to Kilimanjaro came from an Arab geographer and Chinese writer who, at the turn of the 15th century, wrote of a ‘great mountain’ west of Zanzibar. In the early 16th century, a Portuguese geographer noted the existence of an “Ethiopian Mount Olympus.” No one in the West was aware that a “giant, snow-crowned mountain existed so close to the equator until 1848.

If one follows the history of Kilimanjaro–even from a distance–you know that the first known ascent was in 1889 by Hans Meyer, who, along with Ludwig Purtscheller, predicted that the mountain’s ice would disappear within three decades.

In 2001, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicted Kilimanjaro ice cap would be gone by 2020. This latter prediction has proved more accurate than the first. A third of the ice has disappeared since 1990. Meyer, however, was not entirely wrong; more than 80 percent of the glaciers have melted since Meyer’s time, and it is thought that as recently as the 15th century the snows of Kilimanjaro began at the upper edge of what is now the forest zone.

Global warming has a way of killing people on Kilimanjaro. In January 2006, at the Western Breach while approaching what is called ‘Kibo’s Arrow Glacier, three Americans were killed by a rockslide estimated to have been traveling at more than 125 feet per second. The cause of the slide was linked to Kibo’s receding ice, which causes rocks previously frozen to the mountain’s face to loosen and slip. The Western Breach route to the summit, once one of the most popular, has since been closed and may never re-open.

In the summer of 1958 Gina’ husband had no ‘technical skill’ and little equipment when he went for a long walk-up Kilimanjaro, but as the Brits in Arusha would learn, people die from other causes on the mountain, not just heart attacks or AMS.

Phillip would not die climbing Kilimanjaro. On the terrace of the British Club, he turned to Gina and said he wouldn’t leave her. He would not climb Kilimanjaro with her husband.

Africa has always been known for adventure and romance and when the two clash, as they always do, there are many broken hearts and hardships and stories that linger after the couples leave the continent. They become the legendary stories passed on from one generation to the next.

When Arthur left for Kilimanjaro, Phillip did not begin an affair with Gina, he told me immediately. They continued the intense friendship as Gina prepared to leave Africa on home leave once her husband returned. Phillip said that on days when he could see the crest of Kilimanjaro he would pause and stare up at the distance mountain and wonder where Arthur might be on his long climb. This was years before cell phones. Years before an Italian, in 2001, reached the summit and descended in 8 hours and 30 minutes. In 2004, a Tanzanian would beat that time by three minutes. Both of these men ran the entire way.

When Arthur left for Kilimanjaro, Phillip did not begin an affair with Gina, he told me immediately. They continued the intense friendship as Gina prepared to leave Africa on home leave once her husband returned. Phillip said that on days when he could see the crest of Kilimanjaro he would pause and stare up at the distance mountain and wonder where Arthur might be on his long climb. This was years before cell phones. Years before an Italian, in 2001, reached the summit and descended in 8 hours and 30 minutes. In 2004, a Tanzanian would beat that time by three minutes. Both of these men ran the entire way.

Several days passed without any word of any kind about Phillip’s climb and then a district police officer arrived at the school to speak to Phillip’s father. There has been an accident. A European had been killed on the ice cap. One of the Tanzanian porters had come down from the mountains to tell him it was Arthur who had died.

His father and mother and the English colonial officer came around the side of the staff quarters to tell Gina the terrible news. As soon as he saw his parents and the uniformed British officer, Phillip knew, he said. Arthur had been killed on Kilimanjaro.

The police officer told Gina that Arthur had gotten up at night to relieve himself and something had gone wrong. He missed a turn and took a tumble in the dark night. It had been raining for hours. Visible was poor. Footing was poor. He was weak from the climb, suffering from exhaustion. There were a hundred such guesses at how he had slipped and tumbled off the mountain side.

Gina went hysterical. Here she was in the middle of Africa, in the midst of people who she didn’t know or accept her, a London shop girl in the class conscience English system. Arthur had been her protector, shielding her from the rigid barriers of the English class system that lived in the colonial world and now he was dead.

Was it really an accident? Had Arthur stepped off to his death, tumbled from a ridge several hundred feet into the icy cavern simply as a way to put an end to his life, knowing his wife was leaving him when they returned home, since she had already told him. As she would tell Phillip later on the beach of Malindi. Their marriage was over.

In the whirl of those days, Gina’s life was taken over by others. Phillip and his father accompanied her from one government office to the next, death papers were signed and she suffered silently through mumbled words of sympathy by every sort of official in the colonial government. An Anglican service with the eulogy given by the Maryknoll priest who had been on Kilimanjaro with Arthur. The casket was carried by Tanzanian ‘boys’ and later lunch was served in the gardens of Philip’s family home.

No one had the proper clothes, Phillip said. They wore their best dresses, wore suits and white ties; it was like a formal reception when someone important came out from Dar on an official visit.

During this intense week, Gina and Phillip were drawn even closer together by the tragedy. As bizarre as that was, he found he could follow her unspoken wishes, was connected to her psyche. “It was quite extraordinary. I have never again been that close to a person, not even my own wife. I could understand Gina’s thoughts; she could read my mind.”

There were endless details of shipping Arthur’s belongings back to England, of Gina packing up, too, and leaving Africa. At some point the women of the school decided Gina must get away for a few days. She needed to go to the coast and rest before leaving Africa.

Phillip was selected as the only one to accompany her to Mombasa where she would get a ship for home. It was decided they should go a few days early, before the ship was due to leave. One of the teachers had a connection with a family hotel in Malindi, up the coast from Mombasa. A few days in the sun would be best for Gina, everyone agreed. She would then take a ship home as other East African colonialists had been doing since before World War I.

Phillip was selected as the only one to accompany her to Mombasa where she would get a ship for home. It was decided they should go a few days early, before the ship was due to leave. One of the teachers had a connection with a family hotel in Malindi, up the coast from Mombasa. A few days in the sun would be best for Gina, everyone agreed. She would then take a ship home as other East African colonialists had been doing since before World War I.

And so Gina and Phillip went to Malindi and the Blue Marlin, the hotel on the Indian Ocean, and where they would be alone and together.

Phillip and Gina arrived in Malindi together but not as a couple. It was crowded and rooms were scarce, but because of the connection made by the teacher in Arusha word had reached the Blue Marlin about Arthur and Kilimanjaro. Gina was given the honeymoon suite isolated from the other rooms, overlooked the Indian Ocean, yards from the water. Phillip was given a small room rented to PCVs like myself, without hotel amenities, though breakfast tea was left on his doorstep early each morning.

Gina and Phillip stayed at the Blue Marlin for five days. On the third night they made love for the first time. “It kept coming at us,” Phillip explained to me on the beach that winter of ‘69, eleven years after he had first arrived in Malindi with Gina.

“Like an approaching storm,” he explained. “We could feel it on the horizon. A dark massing of clouds which were unavoidable. We kept waiting, all tense about what we knew was inevitable. Finally, it swept over us as the rains do in East Africa.

“It was magically and intoxicating and sad. Gina wept in my arms after we had sex. We never left her room. We had our meals delivered to us.”

Phillip and Gina made grand plans of a life together, of returning to England where he would finish his schooling and she would find work. They would marry and live happily ever after.

Phillip stopped talking. He had fished out a cigarette and was staring at the sea, seeing nothing in the dark night. I found myself concentrating on the rhythm of the waves and half afraid that someone–April perhaps, returning from putting the children to bed–would interrupt Phillip before he finished his tale. I couldn’t imagine myself going up to this stranger the next morning at breakfast and asking, “Say, buddy, what happened with you and Gina?”

“She left me on the morning of our last day,” Phillip went on quickly, summing up. “We had plans to return to Mombasa in the early afternoon. The ship wasn’t scheduled to leave until evening. Gina sent me into town that morning to buy items for the trip. It was her ruse to escape. The owner’s wife had arranged for a car to drive her to Mombasa. When I returned from the village there was a long letter saying all the things, I guess, one says at such a time. She had left it on the bed. The letter was written on Blue Marlin stationary.”

He went on to say how she wrote she couldn’t do this to him, that it was all impossible. She was too old for him. She told him over and over how much she loved him, and that she would never forget how he saved her life. She begged him not to follow her to Mombasa.

“I didn’t follow her,” Phillip told me. “As upset and crazed as I was, I also knew at some place in my mind that she was right. We had no future away from Africa. Africa was our paradise. So when I say I knew someone who had died on Kilimanjaro, I meant Arthur, of course, but also, I mean what had happened to me here at the Blue Marlin. I died, too, when I was a boy.”

He stopped again. I looked up and saw April was returning. She was striding through the brightly lit hotel lobby, coming to us like the sun rising, and Phillip said one more thing, and that was the last time he mentioned Gina.

“Whenever I’m home to London, I go into Harrods and wander the floors looking at the shop girls behind those endless counters. I half hope and half fear I’ll see her. It is a fantasy I have written and rewritten in my mind thousands of times. I have never seen her again, but that daydream, out here in the Africa bush, enchants my life.”

With that, he stood and welcomed April, offering his beach chair to her, then he turning to me and smiling, asked, “Can I get you another pint, Yank?”

John Coyne (Ethiopia 1962-64)

A beautiful story very well told. Thank you John.. (in my old(er) age i am fascinated by “love.” Nice addition to a growing collection

John,

What an enticing read! In going through your text, I could not escape the wisps and strands of a Hemingway-esq’s presence in your delivery.

John – “To Die on Kilimanjaro” is an exquisite moving story and so elucidates the E African colonial culture. Also Ioved all the interesting archival background on Kilimanjaro.Your vivid story evokes so many memories – of teaching in Arusha , Tanzania (Wofford Global Service Fellowship) and partly climbing Kilimanjaro. I never thought when I went to E Africa that Kilimanjaro would be so magnetically alluring and that I would be meeting-up with the deep traces of Hemingway and the Carters’ presence there.

I stayed in a hotel at the base of Kilimanjaro serendipitously in the room where Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter had stayed and was mesmerized by their description of Kilimanjaro and their climb to the top. During that time, I also became aware that Hemingway had been a guide in Kilimanjaro as had his son Patrick who stayed on for decades as an environmentalist of sorts. Hemingway wrote “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” in Key West (published 1936). Your vivid story ignited a desire for another visit to E Africa! – hopefully soon. Geri

Quite a story! Adds to my fear of going to high places that are bitterly cold. I’ve been to the base of the mountain several times, but I never had any desire to spend the six days required to get to the top.