Time for Peace Corps to Refocus Mission by RPCV David F. Mayo

The agency’s foe and foil were clear in 1961. To counter the spread of communism in newly independent states, it enlisted a post-World War II generation of American idealists to share our country’s new affluence around the globe.

Overseas, Peace Corps volunteers inspired trust in democracy by teaching citizens of poor nations skills they requested in their languages and communities. At home, Peace Corps volunteers promoted international friendship by showcasing beneficial values and practices learned abroad. Everywhere, Peace Corps volunteers learned to innovate, withstand hardship, honor commitments and appreciate the power of humble efforts to help others.

Three policies underpinned that mission. Host-community ownership was promoted by having local people use a bottom-up development model called Participatory Analysis for Community Action to choose volunteer activities and by offering customized skills training for 211 different projects within 50 technical interventions. Regulatory capture was prevented by making the Peace Corps independent of the United States Agency for International Development and by barring most Americans from holding staff positions at the Peace Corps for more than five years. And volunteer empowerment was encouraged by trimming the tooth-to-tail ratio of volunteers to staff to 10:1.

Sixty-two years later, the Peace Corps’ adversary and recruits are much different. Internationally, China replaced the Soviet Union as the West’s primary competitor in many developing nations and substituted major economic leverage for person-to-person ideological indoctrination as its method. Domestically, lingering uncertainty caused by the Great Recession of 2007-09 prompted a new generation to think about career ladders in addition to the needs of others.

The policies that guided the Peace Corps in the 1960s also changed.

First, host-community choice has diminished. It started in 2010 when, to protect its share of the American volunteer market, the Peace Corps began reducing projects host countries could select from 211 to 60 on the assumption the remaining ones would provide volunteers “highly focused on building a career” with “an unmatched opportunity for professional growth” and still help local beneficiaries. The death blow came a few years later when the Peace Corps required volunteers to follow “standardized logical project frameworks.” Formed by “a consultative process, involving host government representatives, non-governmental organizations, other project sector experts, counterparts, Volunteers, and staff” rather than by the dictates of host-community members as contemplated by PACA, LPFs now limit the work a volunteer can perform to a menu of activities set by people mostly from outside the volunteer’s community.

Second, there are signs of regulatory capture. Since 2002, the Peace Corps has ceded programmatic control of hundreds of volunteers annually to USAID’s Presidents Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief; entered a USAID-Peace Corps Global Interagency Agreement to integrate activities; appointed USAID veterans to top Peace Corps positions; and changed the ratio of volunteers to staff from a trim 10:1 in the ’60s to 2:1 in FY 2020 and an inverted 1:4 in FY 2022, raising concern that the agency may be inefficient and focused on preserving itself.

Third, trust in the initiative and resilience of volunteers has wavered. How else can one explain the change in the ratio of volunteers to staff from 10:1 to 2:1 to 1:4 and the substitution of activities scripted by outside experts for those designed by host communities aided by volunteers?

Without a doubt, an organization with a vital mission must change to meet demographic, technological, social, legal, economic, and political realities. Remaining stagnant will make it ineffective, inefficient, inequitable, and unsustainable.

The question is whether the Peace Corps still has a vital mission. It did when service-oriented American volunteers combated person-to-person Soviet propaganda by working for the sake of foreign community members on projects they chose. However, China’s substitution of massive economic aid for person-to-person diplomacy and the Peace Corps’ new preference for expert control of community activities, for USAID integration, for an outsized staff, and for promotion of volunteer careers rather than volunteer service has raised doubts.

A fresh review of the Peace Corps’ mission and policies seems appropriate. Debate then can begin on whether infrastructural aid is needed more than person-to-person diplomacy to counter China’s growing economic influence abroad; on whether older skilled volunteers are needed more than young generalists where person-to-person diplomacy remains viable; and on whether contracts with nongovernmental entities are better sources of volunteers than a bureaucracy. The self-sacrifice of hundreds of thousands of upstanding American volunteers and trainees who made life better for millions warrants it.

By David F. Mayo

March 24, 2023

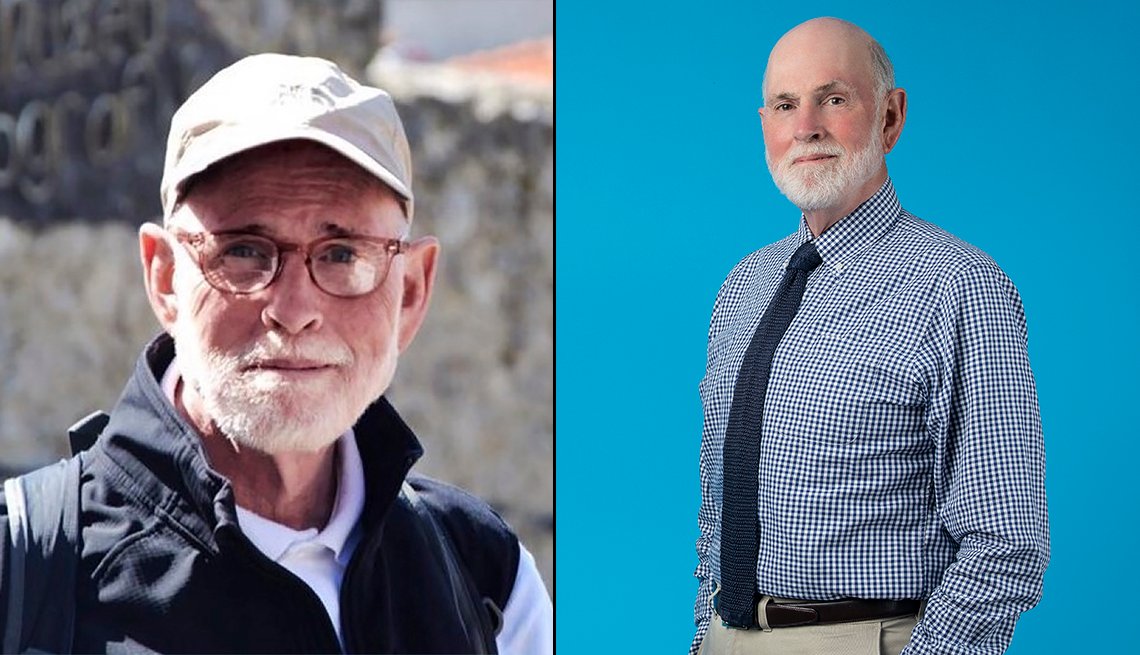

Peace Corps volunteer David Mayo, 76, Spokane, Washington, in two photographs; left, while on assignment in Albania, and right, photographed May 18, 2021 in Grapevine, Texas.

For 11 years, David Mayo’s life followed a traditional path. He went to law school, clerked for a federal judge and practiced corporate law. But as he was busy representing individual clients and businesses, he realized that he wasn’t living up to the values he and his brothers learned from their parents.

“Both of my parents were teachers, and they had a common bond, a real mission and philosophy of helping people and serving the public,” says Mayo, who lives in Spokane, Washington. “They grew up through the Depression and they saw people starve. So, the basic idea was if you take more than you need, you’re harming others. And somebody who has a lot has a duty to give back.”

He and his siblings have taken that credo to heart. His oldest brother served in the Navy, becoming a vice admiral, and his other brother worked for the National Transportation Safety Board.

In 1988 Mayo decided to quit law and spend the rest of his life as a humanitarian volunteer. He began at home, serving in VISTA and Teach for America. Then he went global and began what would be a decades-long journey with the Peace Corps and other international organizations. From Moldova to Georgia to Namibia to Cameroon, Iraq and Albania, Mayo has used his legal skills and the knowledge he gained from getting a master’s degree in public health to — as he puts it — “go out and try to help people define their own paths.”

“I’ve sacrificed making a lot of money but who cares,” Mayo says, “as long as you can fashion an identity and follow it for the rest of your life. It’s been a real calling. It’s been wonderful for me.” In Cameroon, for example, Mayo used his legal background to help create a juvenile justice program to help kids who had gotten in trouble get off the streets into a diversion program.

Mayo was in Albania helping local organizations get funding and manage programs for people with disabilities, disadvantaged women and impoverished students when the pandemic forced his evacuation. And at age 76 he has already applied to go back overseas once the Peace Corps begins deploying volunteers again.

When he got the Peace Corps email asking if he was interested in helping the COVID-19 vaccination efforts, “I jumped at it,” Mayo says, “because my whole interest in volunteerism is to be involved helping the public and this had all the earmarks of that — being part of a team and together we’d be doing our best to eradicate a public health emergency.”

David—-quite a thoughtful narrative. i would love to talk about it. Give me a call at 202 360 6037 (I am on the East Coast) when it is convenient for you. John Chromy India III (1963-65)

Well said.

The lowering of the volunteer-to-staff ratio can be well explained by noting that during the pandemic Peace Corps did not reduce staff (for example, national staff were not laid off) whereas volunteer numbers have only recently begun to creep up with program re-entry. Last time I checked there were only 900+ PCVs in 47 countries.

I am not ready to accept the author’s thesis based on the evidence presented.

agree.. The Covid pandemic altered the statistics, not policy. Staff were retained and working hard on revamping systems and programs… ready to build back fast when Covid permitted.

David,

Your suggestion is timely as it begins to answer this question: while the world has changed greatly since 1961 when Peace Corps entered the NGO market (non-governmental institutions), has Peace Corps changed to address this evolution? In 1961, there was only a handful of NGOs, e.g., CARE, Catholic Relief, etc. Today, there are thousands of NGOs, with USAID providing funding to hundreds of them annually. Thus, young people have a wide variety of choices if they want to work abroad with NGOs similar to Peace Corps.

When one reviews the countries where Volunteers can now return, it doesn’t begin to address this change. For instance, Volunteers returned to Belize to Teach English as a Foreign Language. This seems to ignore the fact that English is the official language in Belize, the only country in South America with this language designation. While learning English is important, it should be linked to its provision of a doorway to a more technological world, allowing its students to compete in this new economic environment.

David: If you read these comments, you may be interested in a report I co-authored with Kevin Quigley back in 2008. It has lots of ideas for refocusing the mission of the Peace Corps, to bring it into the 21st century. I’ve written a number of other pieces on how to make the PC more relevant that have been published , beginning in 2003, in places like the WorldView magazine. Here is a link to the page on the Brookings Institution website where you can download our 2008 report:https://www.brookings.edu/research/ten-times-the-peace-corps-a-smart-investment-in-soft-power/

David: I assume the site will provide you with my email address. Give me a shout. Jay Hill