The Peace Corps, RPCV Tom Scanlon, and the President of Notre Dame

© 2022 University of Notre Dame

June 15, 2022

In a speech to college summer interns in 1962, President John F. Kennedy stumped for the Peace Corps international volunteer organization he created by telling a motivational story about Tom Scanlon (Chile 1961-63), a graduate of Notre Dame University.

The president didn’t mention that Scanlon was a 1960 Notre Dame graduate or that the “friend” who told him the tale was Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, C.S.C. President of Notre Dame. Nor does the history timeline on the Peace Corps website mention the 45 young people who trained at Notre Dame and landed in Chile about a month after another cohort (Ghana) is celebrated as the first group to serve.

Ditto for a recent documentary celebrating the Peace Corps’ history, which didn’t mention the role Father Hesburgh played in helping Sargent Shriver make Kennedy’s vision possible. Even Father Hesburgh hints at some secrecy in his 1999 memoir.

“Everybody knows about the Peace Corps, but relatively few people know that Notre Dame played a pivotal role in the earliest beginning of the program,” he wrote.

Notre Dame has had a close relationship with the Peace Corps from the beginning that continues to this day. The University has sent 921 volunteers to serve since its start, including 17 who had to be evacuated in March 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic began. Many returned Peace Corps volunteers who work on campus said the challenging restart of the service program this summer is a good time to remember its campus connections.

On March 1, 1961, Father Hesburgh walked out of an office near the White House that he used for his Civil Rights Commission work. He ran into his former legal secretary, Harris Wofford, and his friend Sargent Shriver, who called him over to excitedly show him a draft of the executive order creating the Peace Corps, which they expected Kennedy to sign that day.

Later that night, the pair called Father Hesburgh and asked him to provide a pilot project to begin the Peace Corps. Father Hesburgh told them to pick between Bangladesh, Uganda and Chile — three places where the Congregation of Holy Cross had worked for many years. They chose Chile, so Father Hesburgh convened a group of Latin American scholars for lunch the next day to propose ideas.

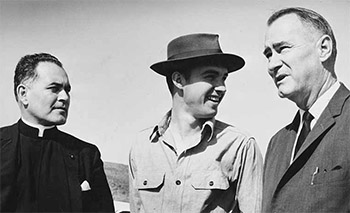

Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., Peace Corps Volunteer Edward Tisch, and Walter Langford in Chile, April 1962. Langford, the chair of Notre Dame’s Modern Languages department, was tapped by Father Hesburgh to lead the Peace Corps program in Chile for its first two years.

Tom Scanlon and the PCVs who trained at Notre Dame traveled to Chile by ship, arranged by Father Hesburgh.

Father Hesburgh sent their plan to Shriver and didn’t hear back for weeks. Finally, Shriver admitted that some people were “gun shy” about the project becoming too Catholic, especially since Shriver and Kennedy were also Catholic in an era when that was a political liability.

In response, Father Hesburgh brought on board the Indiana Conference of Higher Education, and he went on a reconnaissance trip to Chile with an administrator from Indiana University. They found little interest in their original plan to teach literacy through radio programming, but they formed a partnership with the Institute for Rural Education, which taught subjects like crop rotation, animal husbandry, hygiene and nutrition.

Scanlon recalled that Father Hesburgh, who personally recruited him to join the Peace Corps, welcomed all 45 volunteers by name when they arrived for training on campus — he’d memorized their names from provided pictures.

“It was a period when America’s reputation as the leader of the free world was declining,” Father Hesburgh wrote, “and many of our own young people needed a constructive outlet—for their own pent-up idealism.”

Commitment Test

Father Hesburgh starts the Scanlon story — the one that tickled JFK — this way: “He hardly knew a horse from a cow, but he organized farm cooperatives that are still in existence today.”

Scanlon had heard about three remote villages on top of a nearby mountain that the police and government avoided. He climbed up and talked to the communist leader about treating the sick and increasing profits from a special wood harvested there. The leader responded with a test of Scanlon’s determination: If you want to discuss it, come back in June when the southern hemisphere winter fills the mountains with snow.

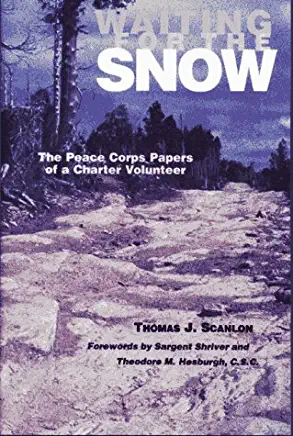

Father Hesburgh visited every volunteer across Chile to deliver a certificate signed by Kennedy. Scanlon told his mentor he was “waiting for the snow,” a phrase that Kennedy borrowed and that Scanlon would use for the title of his memoir.

“I certainly saw our challenge as putting the best foot forward for the United States.” —Tom Scanlon

Unfazed by the ideological battle of the era, Scanlon and a nurse rode horses up the mountain in winter weather to spend a week in the villages. The nurse used penicillin to clear up a skin condition plaguing the village children, and Scanlon organized a cooperative to get better prices for the cypress wood called alerce.

The shocked leader responded: “I may be a Communist, but if you two are any example of what Americans are like, I’m all for America.”

In a pre-internet era, Scanlon learned that Kennedy had used the story when a photographer showed up a week later and told him about the speech. “Father Ted was like my PR guy,” Scanlon joked. “I certainly saw our challenge as putting the best foot forward for the United States.”

Notre Dame served as a training center for the Peace Corps for five years, until Father Hesburgh said the rules and regulations of the bureaucracy led him to conclude that the University had made its contribution.

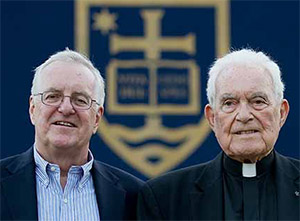

Tom Scanlon with President Emeritus Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, C.S.C. outside the Morris Inn. Scanlon was part of the original group of volunteers for the Peace Corps and was on campus for a gathering of Peace Corps volunteers, July 29, 2011.

“It was, and still is, a beautiful concept, a fitting legacy: Wage peace, not war,” Father Hesburgh wrote.

After returning, Scanlon earned a degree in international relations, worked at USAID and joined a project in Mexico before starting his own international development consulting firm in 1970.

“The Peace Corps just exposed me to a whole different world of exciting opportunity,” he said. “I’ve been running my company now for 52 years. That’s a pretty big impact.”

•

Read more of the story at “Origin Story: The Peace Corps began in part on the campus of Notre Dame.”

Thanks for sharing this story of the role Notre Dame played in the early days of the Peace Corps. Waiting For Snow is an excellent account, and as a graduate of Notre Dame’s graduate school (after I had served as a PCV in Chad), I celebrate Tom Scanlon’s unique role. We are lucky that Father Hesburgh was willing to act as a sort of midwife.

Hesburgh & Scanlon

Scanlon & Hesburgh

Either way, they made a great team and are legendary pillars in the foundations of our Peace Corps