The Peace Corps in the Time of Trump, Part 2

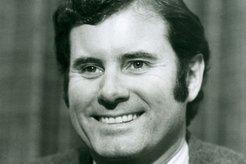

Nixon was no fan of ‘anything’ John F. Kennedy created. The Golden Age of the Peace Corps was over. The New Frontier for this agency came to an end on May 1, 1969, when Joe Blatchford was appointed the third Director and the second Republican to hold the job. (Jack Hood Vaughn was a Republican.)

Blatchford had grown up wealthy in Beverly Hills where his father was involved with finances for the motion pictures. He attended UCLA and was captain of the tennis team. In 1958, when then Vice-President Nixon was charged by a mob in Venezuela, Blatchford began to think about what could be done to improve relationships between the U.S. and Latin America. With tennis friends and jazz musicians, he dropped out of college for a year and went on a goodwill tour in Latin America, playing tennis and jazz. He raised money for this venture with funds from family, friends, and foundations.

Returning home in the fall of 1959, he started the non-profit social action program Acción six months before the Peace Corps was launched on March 1, 1961. Shriver heard about Blatchford and invited him to a meeting at the famous Mayflower Hotel where the Peace Corps legislation was being crafted by Shriver, Wofford, Wiggins and Josephson. Blatchford was even asked by Shriver to incorporate his ‘tennis goodwill tours’ into the new government effort, the Peace Corps. Blatchford declined. He wasn’t a Democrat. He wanted his own private program. Acción continued to round up college students to work in Latin America on community projects, building schools, digging wells, doing community development.

Elizabeth Cobbs Hoffman points out in her book, All You Need Is Love, that in the nine years before he was appointed Peace Corps Director, Blatchford had fielded over a thousand volunteers, supporting them with private funds from individuals and corporations.

Nixon’s Era

Blatchford didn’t work for Nixon during the presidential campaign. In fact, he was in Sao Paulo, Brazil, playing tennis when he got a call from Alexander Butterfield at the White House. (Butterfield, as you may know, later became famous during the White Gate investigation when he dropped the hammer on Nixon, telling the Senate Hearing on July 13, 1973, that Nixon had a secret taping system in the Oval Office. That was Nixon’s undoing.)

Blatchford’s profile, however, had come up on the Republican radar and as Cobbs Hoffman writes, “Blatchford looked like a Sixties kind of guy….He was only 34, had dark curly hair and fashionable long sideburns. He rode a black motorcycle to work, which he parked inside the Peace Corps lobby.”

Just the kind of guy Nixon wanted running the Peace Corps.

Blatchford began immediately to move the Peace Corps in what he called, a New Direction. Actually several New Directions. He started by emphasizing the recruitment of skilled volunteers, not the typical BA Generalist. He also established the first “Office of Returned Peace Corps Volunteers.” While Shriver and others from the first decade rolled their eyes at called this a new direction, Blatchford and his staff forged ahead. And some of what he wanted, was new.

His plan had five objectives:

- Recruiting older, skilled volunteers;

- Dropping the ban on families;

- Placing volunteers more directly under host countries;

- Hiring more foreign nationals in overseas offices;

- He set up an office for minority recruitment.

He also went about changing the ‘benefits’ Sixties volunteers had enjoyed, taking away their ‘privileges.’

In the first official act, he…

- Eliminated the book locker

- Eliminated the clothing allowance

- Lowered free air freight for baggage

- Restricted travel to Western Europe

- Consolidated volunteer allowances

- Allowed Country Directors to dismiss volunteers “for the convenience of the Peace Corps.”

The Peace Corps began to shrink in size. It was, in truth, a combination of Blatchford new focus and the Vietnam War. Applications to join the Peace Corps by June of 1970 decreased to 19,022, less than half the number in 1966.

Blatchford wanted, according to Cobbs Hoffman, “to decrease the number of disenchanted youth in the Peace Corps,” as well as correct problems, such as the urban community development assignments in Latin America, which had a high rate of attrition.

Besides wanting more “skilled, older Americans,” he wanted less political types who openly criticized American foreign policy. Again, Cobbs Hoffman writes that one reason Blatchford got rid of the book locker was because he wanted to make sure volunteers would no longer have liberal tracts to meditate on while living in the bush.

Not only fewer people were applying to the agency, there was another problem for Blatchford. Nixon’s new budget in January 1971, included a 30% reduction for the Peace Corps. The White House plan wanted to cut the number of PCVs from 9,000 to 5,800. Nixon was, secretly, bleeding the Peace Corps to death.

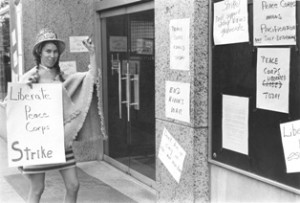

While this was happening Peace Corps volunteers and staff were demonstrating against the War in Vietnam. In the fall of 1969, Blatchford fired twelve volunteers for political activities. In September 1969, The Committee of Returned Volunteers (CRV) issued a statement, saying, “We have come to the unavoidable conclusion that the Peace Corps should be abolished.” That October, on the 15th the first Vietnam Moratorium Day, more than 150 Peace Corps staff members marched 20 blocks in Washington, D.C. to protest the Vietnam War.

On May 9, 1970, sixteen members of the Committee of Returned Volunteers occupied the fourth floor of the Peace  Corps HQ while other RPCVs picketed outside the building. Among those demonstrators outside the building was Carol Bellamy (Guatemala 1963-65) who would in 1993 become the first RPCV Peace Corps Director.

Corps HQ while other RPCVs picketed outside the building. Among those demonstrators outside the building was Carol Bellamy (Guatemala 1963-65) who would in 1993 become the first RPCV Peace Corps Director.

Into this mix came the creation in 1971 of ACTION with Blatchford as the first director. It was composed of two major volunteer efforts: Peace Corps, the autonomous arm of the State Department, and VISTA, part of the Office of Economic Opportunity. These programs were the “core” of the new agency.

Peace Corps was no longer independent and Joe Blatchford was about to lose his job.

On July 1, 1971, Joe Blatchford’s brief career as Director of the Peace Corps was over. Blatchford was as surprised as anyone. David Searles in his book, The Peace Corps Experience: Challenge & Change 1969-1976 writes that after Nixon’s win in 1972 he called for the resignation of all his political appointees. “Blatchford, ” writes Searles, “turned to a colleague at a post election meeting where the resignations were demanded and said, ‘But I thought we won.'”

Searles would go on to point out that Blatchford “was a Republican, but he held ideas that often seemed liberal, at least to some in the White House.” Such an attitude hasten Blatchford’s departure from the Peace Corps and the Nixon Administration.

Kevin O’Donnell, the country director in Korea became the fourth director, but the days of an independent Peace Corps were numbered. Nixon had “buried alive” the Peace Corps in a new government organization ACTION.

He had gotten rid of Kennedy’s legendary corps.

It was the end of the Peace Corps.

But was it?

It would take another Republican to save the Peace Corps. And this time it would be a woman.

(End of Part Two)

Key Books on the Peace Corps

The Peace Corps WHO, HOW, AND WHERE by Charles E. Wingenbach, A John Day Book, 1961.

The Bold Experiment: JFK’s Peace Corps by Gerard T. Rice, Notre Dame Press, 1985.

Come As You Are: The Peace Corps Story by Coates Redmon (PC/HQ 1962-67) Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1986.

The Peace Corps Experience: Challenge and Change 1969-1976 by P. David Searles, The University Press of Kentucky, 1997.

All You Need Is Love: The Peace Corps and the Spirit of the 1960s by Elizabeth Cobbs Hoffman, Harvard University Press, 1998.

Making Them Like Us: Peace Corps Volunteers in the 1960s by Fritz Fischer, Smithsonian Press, 1998.

Peace Corps Chronology 1961-2010 by Lawrence F. Lihosit (Honduras 1975-77) iUniverse, 2010.

When The World Calls: The Inside Story of the Peace Corps and its First Fifty Years by Stanley Meisler (PC/HQ 1964-67) Beacon, 2011.

We had a clothing allowance?

I would very much like to add Dr. Robert Textor’s classic “Cultural Frontiers of the Peace Corps” to the list of key books on the Peace Corps. Textor was a young cultural anthropologist who was a member of Peace Corps staff in 1961. He also trained Thailand I and maintained ties with the RPCV community during his long tenure as a professor at Stanford.

He was the real author of the “In, Up, and Out” policy that established the five year rule for Peace Corps staff. “Cultural Frontiers of the Peace Corps” is a collection of 15 case studies of early Peace Corps programs, covering Latin America, Asia and Africa. The case studies are the result of field work and place the Peace Corps directly where it should be: In the Field working with Host Country people.

You are right Joanne. It is an important book. I have it. I knew Bob. I don’t have it on this list, as this list just focuses on book

s around the ‘organization’ of the agency, not the work of the Volunteers.

John, I believe that Country Directors, indeed in-country Regional Reps as well as some Peace Corps Leaders, always had the

authority to “dismiss Volunteers for the convenience of the Peace Corps.” Volunteers served “at the pleaseure of the President:” and that authority was delegated to the administrative staff.

Threatening Volunteers with termination was a very real fact of my service in Colombia 1963-65. Male Volunteers/trainees who “questioned” staff could be terminated and their draft boards notified before the Volunteer even arrived stateside. All of us knew that such a termination could result in a statement in our permanent record “unfit for overseas service”. I found it an atrocious situation and saw that threat used arbitrarly. In those days, there was no appeal process. It is one of the reasons I have long advocated that Volunteers have a service contract that would offer some protection.

I didn’t have a clothing allowance. The book locker was fantastic for those of us in locales with no radios or any diversions except for bars. I had Peace Corps issued cheap local made furniture which I was told to give away when I left Ethiopia in 1965. Several university students doing national service were happy recipients.

Yes Mary there was a clothing allowance.

I think Blatchford was responsible for “eliminating ” the allowance from the Peace Corps annual budget. It was a line item.

The history goes back to Colombia I when Shriner outfitted the group with a one off donation of clothing from the President of Sears. Thereafter,the Corps would have to pay; hence the line item.

!

I remember that Levi Strass donated two pairs of levis to every trainee. We wore them throughout training and service. I do remember a clothing allowance.

Excellent summation as always, John, of an important piece of PC history — and certainly deserving of deeper discussion than that about a PCV clothing allowance. That said, however, does any Ethie I remember getting such an allowance?

I never had any allowance, Mary, in Addis Ababa.

In addition to a one-time clothing allowance issued state-side and a book locker, Malaya I was issued a medical kit and a lightweight Egyptian cotton blanket.

The clothing allowance did little good because my house was burglarized and all my cloths except my size 12 shoes were stolen my first week of service.

The books in the locker circulated amongst my school’s faculty and never found their way back to me.

The medical kit was invaluable in treating bouts of dysentery, cuts and infections and the cotton blanket was a great comfort when the nighttime temperature dropped during monsoon season.

I had to return what was left in the medical kit upon departure from Malaysia but was able to keep and still have the cotton blanket stowed somewhere in the attic.

Jim Wolter, Malaya I ’61-’66

The strongest and most effective lesson in democracy we delivered to Somalis during our service was that, although we were employed by the US Government as PCVs, we could and did disagree with our government’s policies, specifically the war in Vietnam., Being opposed to the war and not afraid to express our views, drove home that citizens in a democracy do not have to follow the government’s line, like the Russian, Chinese and Egyptian personnel providing assistance in Somalia.

As for the book locker and clothing allowance, I recall one book in our locker was “I Was A Communist for the FBI,” so it wasn’t all radical liberal tomes. We also didn’t have a clothing allowance and we when we left at the end of our tour, LBJ tried to delay payment of our accumulated pay. I forgot the official reason given but we ultimately received our $1500 per year.