“Teacher” by Kathleen Coskran (Ethiopia)

Foreword

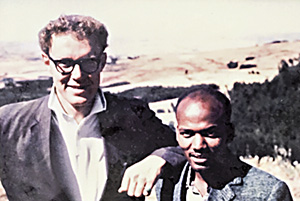

Chuck vaccinating

Chuck Coskran and I were Peace Corps Volunteers in Ethiopia from 1965 to 1967. We didn’t train together though — he was trained in Los Angeles; I, in Salt Lake City. We were both stationed in the capital, Addis Ababa, the first year, but didn’t meet each other until we were assigned to the same summer project, giving BCG vaccinations [Bacillus Calmette–Guérin vaccine primarily used against tuberculosis] in Nekemte.

At that time I was lobbying hard with Peace Corps staff to be transferred out of the city to a village, and, to my great delight, was posted in Dilla, Ethiopia, for my second year. Chuck continued teaching history at Bede Mariam Lab School for talented 12th-graders who were brought to Addis Ababa from throughout Ethiopia.

Following our completion of service in 1967 Chuck returned to the US to work in Peace Corps/Washington as the Ethiopia Desk Officer, which was about the time Joe Murphy became Country Director in Ethiopia.

Meanwhile, I was traveling with my Dilla roommate, Claudette Renner, beginning in Tehran and working our way west. (We had wanted to begin in Khartoum, Sudan and go east, but the Seven Day War ended shortly before the end of our Peace Corps service and when we picked up our passports at the embassy, they were stamped NOT VALID FOR TRAVEL IN . . ., and listed every middle eastern country.)

In those days itinerant American travelers could receive mail at American Express offices in capital cities, and beginning in Istanbul, I began receiving multiple letters from Chuck in every capital city Claudette and I visited saying it was likely he would soon be stationed with Peace Corps staff in Africa, and wouldn’t it be too bad if we missed each other, and perhaps I should come home earlier than I planned.

Well, after four months, I decided to cut my trip short, arrived home just before Thanksgiving. We were married two months later. The next year we moved to Kenya, where Chuck was the Peace Corps Education Officer and then Deputy Director.

We returned to Washington the summer of 1971 where Chuck served as Peace Corps Deputy Director for the Africa Region.

Fast forward 20+ years: Joe Murphy was a frequent visitor to Ethiopia and worked with the Ethiopian government (established after the downfall of the military junta) to negotiate a loan with the World Bank along with President Negasso Gidada. When Dr. Negasso learned of Joe’s earlier Peace Corps connection, he mentioned this amazing Peace Corps history teacher he had had, Chuck Coskran. Joe called Chuck, encouraged him to contact Negasso, which he did, and thus we were invited to Ethiopia.

Dr. Negasso Gidada earned a Ph. D in Social History from the Goethe University in Frankfurt-am-Main, and was an active member of the Oromo Liberation Front while in Europe. After returning to Ethiopia he was Minister of Information in the Transitional Government of Ethiopia and became the second president of Ethiopia when Meles Zenawi (the first president of the new government) became prime minister. Dr. Negasso served as president from August 1995 to October 2001. Following his service as president, he was Minister of Communication of Ethiopia until his death in 2019.

Teacher

by

Kathleen Coskran (Ethiopia 1965-67)

MOST PEOPLE VISITING a head of state don’t look for the cheapest accommodations, but we were returning Peace Corps Volunteers and couldn’t see ourselves staying in the old Ghion or, worse, taking shelter at the new Hilton in the suburbs of Addis Ababa. We wanted to be in the center of town, near the Piazza, where we could step out our door and see goats and beggars and holy men.

The Baro Hotel was cheap — US$12 per night — and the lush vegetation recommended it. Cascading bougainvillea and the hadar abebe bush with its giant red flowers curtained the long, narrow porch in front of the rooms. A bit claustrophobic but perfect for the president’s teacher.

The room was simple, two cots, one lamp that was too dim to read by, and a tiny bathroom with a leaky toilet that kept the floor damp and musky. The proprietor, an enthusiastic young man named Feleke, served us tea, advised us to put our money in his desk drawer so we wouldn’t be robbed and wanted to discuss land policy. I admired the luxuriant red flowers. I will give you seeds for your country, Feleke said. It is too cold, I said. You can try, he said.

That’s what people were doing everywhere — trying. A doe-eyed girl scrubbed clothes at a washboard in the corner of the courtyard as we drank our tea. Just beyond, an old guy scrubbed a Land Rover. On the streets, in the Piazza, young children were begging or polishing shoes or selling gum. Only the young men seemed not to be trying; they stood on corners everywhere, talking, watching, laughing, uncomfortably idle. Many were missing limbs—the most recent casualties of the thirty-year war with Eritrea.

By the second day of our return to Ethiopia, we had slipped into life there, hand into glove, in spite of the lepers with their smooth, stubby fingers and the beggar with his legs so swollen with elephantiasis that he had to be dragged from corner to corner. We weren’t oblivious to the suffering, but were hopeful that there was more to the story. Ethiopia had survived a bloody coup, civil war, terror and counter-terror, starvation, and some good men now held the future of the country in their hands.

Chuck with his student Negasso Gidada

We had come to see one of those men, my husband’s student, Dr. Negasso Gidada, the president of Ethiopia. In a letter to Chuck, President Negasso had said, “I sometimes think that the years of struggle up to 1991 and my present position are partly the result of your lessons and the discussions we then had . . . you have contributed a lot not only for my own life but for the development and processes of struggle of our country . . ..”

We had arrived on a Saturday; Chuck called on Monday to set up the appointment. The secretary was guarded at first, then recognized his name. “Oh, you are the President’s teacher,” she said. “I will call you back.” She called an hour later to say we were to be at the National Palace at 10:00 am on Wednesday, the National Palace that had been the residence of His Imperial Majesty, Haile Selassie I, when we were Peace Corps Volunteers. What business did we have in going to the National Palace?

For the next two days we tried to be tourists, but the impending visit hung over us. We were nervous. We did visit the University Lab School where Chuck had taught 12th grade history to Negasso Gidada, a bright boy from the remote village of Dembi Dolo. Chuck’s journal entry for April 15, 1967, reads “Negasso spent the night with me. He is troubled by this whole mess [His Majesty’s response to student demonstrations], determined to stick it out with the rest of his fellow students, but worried.” We visited Haile Selassie Secondary School where I taught. We walked by the houses we had lived in. We visited the national museum and saw casts of the bones of our tiny, common ancestor Lucy, called Birkinesh in Amharic . . .“she is wonderful.”

We were dressed and pacing by 9:00 Wednesday morning. Feleke had arranged for the cab, and by the shy gathering of neighborhood children, night watchmen, and young women who worked at the hotel, it was clear that everybody knew that the president’s teacher was about to leave for the palace.

WE ARRIVED AT THE BLACK IRON GATES too early, but the guards were expecting us and let us in, on foot, unescorted. The spacious grounds had wide paths, manicured lawns and the air was fragrant with flowering mimosa and frangipani, but it was absolutely silent, not even a gardener in sight. We held hands and walked slowly towards the palace in the distance.

A soldier met us inside the foyer of the large sprawling house that was the palace, showed us to an anteroom, told us to sit on a narrow, overstuffed sofa, and left us. We were too early. We stared at huge framed lithographs of hunting scenes, intricately carved tables, a mounted head of some kind of antelope, a large Oriental rug on the floor, silver trays, china figurines. Nothing Ethiopian — gifts to the head-of-state, we decided. We wanted to browse, to look at everything more closely, but we couldn’t move. We were in the palace of the president and had been told to sit, so we sat.

At exactly ten o’clock, we were escorted to President Negasso’s office. He rushed around his desk to take Chuck’s hand in both of his, to hold on to him, to welcome him after so many years. He was a gracious man, balding, bespectacled, in a double-breasted suit, gold and black tie, neat mustache, with a soft voice and unassuming manner, so happy to see Chuck and, he said later, a bit surprised to find himself in Haile Selassie’s office. He had studied history and planned to devote his life to the history of the Oromo people, but like so many bright young Ethiopians was out of the country on scholarship during the coup of 1974 and couldn’t return. In fact, he was alive because he was caught outside Ethiopia rather than inside. Most of the students Chuck asked about were dead, either “. . . executed by Mengistu [the leader of the coup] or [they] sacrificed their lives in the long struggle for democracy, peace, and development.”

It was an emotional hour. So much had happened since they were teacher and student. They talked about the recent history of the beloved country, about their own children and their hopes for the future. They did what good men everywhere do which was to speak regretfully about the past and hopefully about the future. They had gifts — the teacher brought books for his student, and the president offered his teacher a copy of the new constitution, asked him to comment on it, and also presented a leather book with stamps issued since the dictator was deposed.

When it was time to go, I asked if I could take their picture together. As they stood for the photo, President Negasso moved from Chuck’s right to his left, thus positioning his teacher as He-Who-Stands-At-My-Right, the traditional position of honor. “I’ll not soon forget that,” Chuck wrote in his journal.

When it was time to go, I asked if I could take their picture together. As they stood for the photo, President Negasso moved from Chuck’s right to his left, thus positioning his teacher as He-Who-Stands-At-My-Right, the traditional position of honor. “I’ll not soon forget that,” Chuck wrote in his journal.

An hour later we walked back through the manicured grounds, through the iron gates, on to the road, found a taxi, haggled for the fare, were silent on the drive back. It was too much to talk about in the back of a cab. And when we got to the Baro Hotel, where a woman was scrubbing the long porch in front of our room, where two men were arguing, where a boy with a rough wooden box offered to polish our shoes, we lingered in the street next to the profusion of red flowers from the hadar abebe to take it all in. Everybody was trying. It was wonderful.

•

Kathleen Coskran (Ethiopia 1965-67) is primarily a fiction writer but is currently working on a book about the lack of justice in the multiple criminal justice systems in the United States, based on her 25-year friendship with James Colvin, who has been incarcerated for nearly 50 years.

Kathleen, thank you for posting this wonderful narrative. Chuck was one of my favorite PCVs in the mid-1960s when I was a staff man. In addition to his excellent teaching, he had an Irish eye for socializing, and he was the only PCV to finish a bottle of bourbon with me in Addis Ababa. I had lost track of him and wondered where his post-PC life had taken him. He must have married well and continued that adventurous spirit he displayed as a young man. I’m so glad for both of you. Keep up the great work!

My name is Tekola Beyene from Dire Dawa. I was student at Lab School (Bedemariam) at the same time Negasso attended. We were in the same dorm. The director was an American. I forgot his name. You might have been my teacher. I loved the way you shared the detailed sequence of events you came across. Thanks to my former teacher at Dire Dawa, Bill Donohoe, who was among the first Peace Corps group, opened the door for me and then all is history.

Thanks to all Peace Corps whose sacrifice have changed the life of many for better.

Thanks for sharing your experience.

Kathleen, this is a wonderful story, and very visually descriptive, as your writing always is. I got to Ethiopia almost a half century after you, in 2010, doing an audit of the post. Thank you for sharing this.

Kathleen,

Wonderful story; rich descriptions. Thank you.

Carolyn and I were posted in Debra Marcos, Gojam, Province from 1962-65, where I taught history and Geography and coached track. We gave BCG shots in Harare in the summer of 1964! Thank you for that information of what BCG meant!!

When I was a boy in the early 50’s, my mother, every morning, would read to us from the Presbyterian World Missionary Book of Prayer about the various missionaries around the world. I well remember reading about a local missionary in Dembe Dolo, Ethiopia named Blind Gidada. He had this named Blind, due to being blind. My sister, age 88, vividly recalls reading about him. I predict he was a close relative, maybe even father of President Negasso Gidada. My sister speculates he had a difficult time marrying due to his blindness. All of this must have had a major impact on President Gidada.

We live in Winona, Minnesota and we look forward to spending some quality time with the two of you.

Carolyn and John Collins