Talking with Paul Theroux

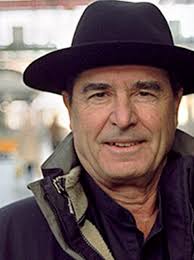

. . . an interview by John Coyne (Ethiopia 1962–64)This is an interview I did with Paul around 2002. Since he is speaking in Washington this Saturday, March 7th, I thought I would republish it to fill in everyone about his early years in the Peace Corps.PAUL THEROUX (Malawi 1963-65) has produced some of the most wicked, funny, sad, bitter, readable, knowledgeable, rude, contemptuous, ruthless, arrogant, moving, brilliant and quotable books ever written. In doing so, he has been in all regards the most successful literary and commercial writer to come out of the Peace Corps.For those not familiar with Theroux’s life, he was born in Medford, Massachusetts in 1941, one of seven children, and studied premed at the University of Maine before transferring to the University of Massachusetts and taking his first creative writing class from the poet Joseph Langland. He graduated in 1963 from the U. of Massachusetts and went into Peace Corps training at Camp Radley, Puerto Rico in October of that year and finished his training at Syracuse University before departing for Malawi (then called the Nyasaland Protectorate) where he taught English at Soche Hill College.His successful writing (i.e. getting paid for what he wrote) began in the Peace Corps in 1964 and his early published works were about the experience of being overseas in Africa. Three of his early novels are set in Africa: Fong and the Indians, Girls at Play, and Jungle Lovers. He has written directly about his Peace Corps experience in My Secret History and My Other Life.

In an article I wrote for our newsletter and website, I detailed Theroux’s fight with the U.S. Ambassador to Malawi over the anti-Vietnam war editorials that Paul published in the Peace Corps newsletter, and Theroux’s involvement with a failed coup d’etat which led to him being declared persona non grata by Malawi Prime Minister, Hastings Banta, and his termination from the Peace Corps.

Kicked out of the Peace Corps and Malawi, Theroux went to teach English at the famed Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda. Here he met not only his future wife, Anne Castle but also V.S. Naipaul. His first son, Marcel, who is today a novelist, was born in Uganda in 1968. It was at this time that an angry mob at a demonstration threatened to overturn the car in which Anne, then pregnant with Marcel, was riding, and Theroux made the decision to leave Africa.

But in many ways, he has never left the continent and has written often about Africa and has traveled back several times to write travel pieces. Now he has written a wonderful travel book about Africa and a trip he took two years ago, Dark Star Safari: Overland from Cairo to Cape Town.

When the book was published in England several months ago, I contacted Paul in Hawaii, where he spends half the year, and we corresponded by email for several weeks. This interview is the first one Paul has done for a Peace Corps publication and it gave me the opportunity to ask some of the questions I have been wanting to ask him for years. Paul was quick to reply.

You’ve written that you had trouble being cleared by the FBI when you applied for the Peace Corps. Do you know why they had a hold on you?

Yes, they told me — Get this: In the summer of 1961 I was in San Juan, Puerto Rico. I worked at the Caribe Hilton and I put this fact down on my PC application. FBI agents in San Juan checked out my employer and also went to my old address in San Juan, where the landlady innocently reported that I was living with a woman upstairs. This irregularity meant that I did not meet the PC standard of morality and my application was turned down. I got a phone call. “Too bad, Paul.” I said, “May I write you a letter?” The man said okay, and I did and was accepted at the last moment.

What was your Volunteer assignment?

My group was “Nyasaland III” — altered to “Malawi III” after independence. I was a teacher in a rural school.

When you stepped off the plane in 1963, what was your first reaction to Africa?

Great happiness, intense excitement, boundless hope.

You were in-country when Nyasaland became Malawi. What were those days like?

Very exciting to be present at Malawi’s independence. Remember, this was a time when people had no intention of emigrating — leaving their country and going to work in the USA. Malawians were committed to staying, working, building the nation. All that changed in the 1970s.

What was the biggest contribution that you made as a Volunteer?

I don’t know. I had lots of very good students. Last year, traveling to write Dark Star Safari, I stopped in Malawi and bumped into Sam Mpechetula. I had last seen him as a little barefoot kid in my English class. He was now a big gray-haired man, wearing nice shoes, married, and with three or four children. He was a teacher. He clearly remembered me and our classes and he said that other students had done well. I suppose that’s something.

When you came to Africa, were you thinking then that you would be a writer?

I had written a great deal while I was in college — stories, poems, plays, and had started a novel.

You’ve written a great deal about Africa and the Peace Corps. Your first published writings were letters home from overseas. Can you remember the first essay (letter?) that you had published?

The first essay — “Letter from Africa” — was in The Christian Science Monitor in 1964. The first poem in The Central African Examiner in June 1964. I remember the dates well because I was eager to be published.

Your first three books were set in Africa: Waldo, Fong and the Indians, and Girls at Play. If I’m correct, Girls at Play is the first novel by a PCV that has a Peace Corps Volunteer as a character. Can you describe the backgrounds of these books?

Waldo was a novel I had started before going to Africa. I finished it in Malawi in 1965. I got the idea for Fong & the Indians in Kampala and was influenced by having met V S Naipaul there, as well as by the fact that Indians were being persecuted in Kenya.

Though I denied it at the time, for legal reasons, I based Girls at Play on a school in Kenya where my then-fiancée was teaching. I wrote it in 1968 in Kampala and it was published in 1969 when I was living in Singapore. One of the main characters (who gets raped and murdered) is a PCV.

Did you base that character in Girls at Play on any particular PCV?

No, only on the sort of innocence and naiveté that led some PCVs, including me, into dangerous territory.

For a time, the Peace Corps staff in Ethiopia used your essay “Tarzan is an Expatriate” as training material for new PCVs. How did you come to publish that, and where was it published?

In March 1967 at Makerere University I was asked to give a lecture to the new VSOs. My subject was how Tarzan and Robinson Crusoe were models for the expatriate-in-Africa experience. The Tarzan essay was published in Transition magazine later that year and caused a fuss.

Speaking of expatriates — have you ever been taken with the Isak Dinesen myth and wanted to write about her and Happy Valley? And with Tom Dooley who was perhaps — metaphorically speaking — the first Peace Corps Volunteer.

There is something about Africa that makes it a breeding ground for mythomaniacs like Blixen/Dinesen and Hemingway and all the rest of them. I can’t stand their purple prose and their patronizing attitudes. I have written about this weirdness in Dark Star Safari.

I have researched the life of Tom Dooley and wrote a screenplay for Oliver Stone on the subject (the movie has not been made). A very complex person, Dooley was booted out of the US Navy for being gay, reinvented himself as a missionary and anti-communist, and was a consummate narcissist, self-promoter and political lobbyist whose ideas helped start the Peace Corps (he was not, of course, a PCV), and also start the Vietnam War. A typical Dooley quote from his hospital in Laos: “Here I am, at the rim of Red Hell (China).”

How did you come to write “The Lepers of Moyo”? Did you work with lepers as a secondary project when you were in the Peace Corps?

On school vacations in Malawi we teachers were supposed to do something useful. I found a leprosarium by the shore of Lake Malawi and worked there — it was called Mua, at Ntakataka. 1,500 people — families of sufferers. It was in many respects a very happy place, though all the people were outcasts.

Leprosy (Hansen’s Disease) has been more or less cured in Malawi, though when it was beset by AIDS I wrote the story, as a reminder of this earlier scourge. The story is based on fact, the setting is actual, but the narrative is fiction.

You taught in Africa in the early 1960s. Why did you decide to return after almost 40 years?

Since leaving Africa in October 1968 I thought of the places I had worked, the people I had known, and the hope we all had. I constantly thought: What happened? I longed to return, and I thought I would do it in the year I turned 60. Dark Star Safari represents one man’s road. Another person could take the same trip and would have different experiences. That’s a truism, of course. This trip was special to me — because the road was in part Memory Lane — and because I loved the challenges. There is nothing in the world more vitalizing to me that traveling in the African bush.

It is wonderful for a teacher to meet a former student and see that he or she is gainfully employed — perhaps as a teacher; and is a responsible parent and homeowner. This happened to me in Malawi and Uganda — wonderful memories. My old friend Apolo Nsibambi — we used to drink and argue in the 1960s — is now Prime Minister of Uganda. I loved seeing him after 30 years. The passage of time is more dramatic in Africa — amazing to witness its effects, for I first set foot there in 1963, which was another age altogether.

You traveled from Cairo to Cape Town by train, bus, taxi, kayak, and often by foot. Why didn’t you fly?

Flying from one capital city to another is not travel to me. Travel, especially in Africa, must be overland and must involve the crossing of borders — negotiating on land, usually on foot, the national frontier. That experience teaches a great deal about the state of the country. Of course, it’s sometimes dangerous and always time-consuming.

Anyone who has traveled in Africa and not crossed a national frontier has truly missed the necessary misery and splendor of the journey. Crossing an African frontier alone suggests why any sort of development is so difficult. I do not recommend this to the faint of heart — even traveling by road from South Africa to Mozambique is no picnic; but from Ethiopia to Kenya, Kenya to Uganda, Tanzania to Malawi, and Malawi into Mozambique (customs post under a mango tree on the Shire River) you learn a great deal.

Also, I don’t fit in. I am a traveler, a stranger, an eavesdropper. I have no status and do not want any. I have an aversion to being an official visitor. I had to borrow a necktie in order to see the US Ambassador in Kampala. I hate official visits — being an honored guest at factories and schools. I often feel like the king or prince in an Elizabethan drama, who puts on a cloak and wanders anonymously in the marketplaces of his kingdom to find out what people really think.

Kenya was in a horrible state when you visited, with widespread government corruption under Daniel Arap Moi and a dejected populace affected by years of corruption and terror. Do you see hope for Kenya after their free elections in December 2002 and the defeat of Kenyatta, Moi’s hand-picked successor?

Kenya’s government has been deeply corrupt. Moi’s government tortured friends of mine. Everyone knew it was horribly governed.

I heard the other day that a man in Moi’s government had stolen “hundreds of millions of dollars.” Imagine that amount of money and the thief who took it. So, now that Mwai Kibaki has won the election and is in power do we say, “Well, all that money was stolen and squirreled away — looks like we’ll have to give you some more.” I don’t think so. My solution would be to forgive the debts of these countries and then after a suitable period of time, make them account for every penny they are given.

You encounter foreign aid workers throughout your journey yet the typical African lives you describe are plagued by what has become routine desperation. What has been the benefit of 40 years of foreign aid?

Not much — which is why the whole issue needs rethinking. My answer about begging [just below] has larger implications in the aid industry, which is a begging-and-donating mechanism. I would distinguish between emergency aid (flood in Mozambique, famine in Zambia, earthquake in Rwanda) and the routine dumping-food-in-the-trough that many agencies practice. Such agencies have taken over the care and welfare of people from governments. Malawi is an example. Foreign agencies run hospitals, schools, orphanages, etc., while the politicians pretend to govern. I am in favor of making people responsible for their own problems. You have floods because you cut down all your trees. You have a famine because the minister sold the grain stocks and stole the money. Unprotected sex causes AIDS. Pointing out the obvious, perhaps, but not many people do it.

As a white man and an obvious traveler, you were constantly approached — even harassed — by beggars. You write about the many times you fled them or turned a blind eye. What are your thoughts on begging?

I am not intolerant of beggars, but maybe a little skeptical sometimes. Even here at home, I say to panhandlers, “Why are you asking me for money for nothing? Do you want fifty cents? If you wash my car I will give you twenty dollars.” The offer of work usually drives them away. Obviously there are many deserving destitute. But for many others, begging is a career. In all cases, handing money over is not a solution.

When you were in Africa in the 1960s many countries, including Kenya and Mozambique, were forming their own governments after centuries of colonial rule. As a traveling observer, how do you think those countries have fared since the end of colonialism?

They have fared badly because of poor leadership, lack of resources, the colonial hangover, the subversion of foreign institutions.

In Malawi and Zimbabwe, Africans told me that when they tried to start a business — like a shop, or a farm, or a bar— they failed because at the first sign of success their relatives showed up and cadged from them, or implored them to pay their relatives’ school fees. That’s a common tale of woe.

But I noticed something else, as well. In the past, people tried to make things work and struggled in hard times — in Asia, in Latin America, in Africa. In the past 15 years, people have given up struggling at home and tried to emigrate. During my trip I heard many stories of emigration. People failing in rural Tanzania do not think of making a new life elsewhere in East Africa. They are headed for South Africa and the promise of work, or else seeking a visa to Britain or the United States. I met many people who wanted a ticket out — so economic failure could be tied to people disgusted with their prospects and wanting to leave. As a traveler in Africa, my traveling companions were often Africans heading elsewhere. Often I said to them, “Why don’t you stay home and fix the problem?” They said: “Let someone else do it.” And I said: “It’s not going to be me.”

You mentioned crossing African borders and how necessary the “misery and splendor of the journey” is. How about the danger? Did you have any experience where you really thought your life was in danger?

I was certain my life was in danger when bandits fired at the cattle truck I was riding in from the Ethiopian border through the northern Kenyan desert. I was assured by a man ducking next to me, “They do not want your life, bwana. They want your shoes.” I also felt my life was in jeopardy in every “chicken bus” and old car I rode in — at great speed, on bad roads, with a young reckless driver at the wheel.

Traveling in Africa, I had to learn patience, humility, survival skills, and to keep reminding myself that I was “prey” To most people I representing Money-on-Two-Legs. I am as risk-averse as anyone else — also, aren’t I a wealthy, middle-aged, semi-well-known American writer who doesn’t need to put up with this crap? The answer is yes and no. I did need to put up with this crap or else there’s no insight and no book.

You describe cities in South Africa and even Harare, Zimbabwe, as relatively orderly with reliable public transportation and a working class. Why is there such a big difference between the cities in the south and the sub-Saharan cities further north like Addis Ababa, Nairobi, Kampala, and Mbeya?

All African cities I have seen are a horror. I tried to avoid them, by traveling in the bush.

Africa is a separate place. Traveling in it, I seemed to be on another planet. I liked this feeling — because the world has shrunk and you often meet people in South America and Asia who regard themselves as living in a suburb or satellite city of the United States.

By having been largely ignored and neglected, Africa has remained itself. Who would want to visit China now that it is an overheated economy of consumer goods and greedy materialists? Pacific islands have remained culturally interesting by being so far away and neglected. Whatever was hoped for Africa in the 1960s — that it would become materially better off, better educated, and healthier — has not come about. But whose hopes were these?

What impresses me about the many African countries that I traveled through from Cairo to Cape Town was how people have survived tyrannical governments, food shortages, disease, and poor or no infrastructure — bad roads, no phones, etc. Of course, the governments need people to be poor and to look distressed in order to get donor money. Malawi is a great example of that. Nothing positive has happened to Malawi since I left there in 1965. Yet in the villages and by the lakeshore and in the bush people go on.

What part of your trip filled you with the greatest hope for Africa’s future?

The knowledge that African friends of mine who were educated — with good jobs in education or health — were encouraging their children (in some cases American educated) to remain in Uganda, Kenya, or Malawi to work “to be part of the process” as one mother said to me — without relying on the Peace Corps or USAID or other foreign donors.

Was there a pivotal moment when you felt utter despair for the African situation?

I don’t feel despair. But it sometimes seems that Africa exists in a sort of shadow cast by the outer world. But Africa is not darker or crueler or harder than other places. Prisoners are tortured by the Israeli government. China interferes with people’s private lives. Women are treated as a separate and inferior species in Saudi Arabia. There is starvation in North Korea. Brazil’s slums are worse than anything in the world. Until recently you could not buy condoms or get a divorce or an abortion in Ireland: maybe still true? There are plenty of barbarities in the world that make Africa seem serene and civilized.

One last question about Africa. Do you think there is still a place in Africa for Peace Corps Volunteers?

Definitely. But it seems to me that every African country should match the program by pairing a local volunteer with a PCV.

Have you thought of a book about traveling in the U.S.?

The hardest place to write about is one’s own country. A man from my home town of Medford, a forgotten writer named Nathaniel Bishop wrote two wonderful books about the US — in one he paddled a canoe from NY to New Orleans, in the second he rowed a small boat. I like solo travel under my own steam. Maybe I will write Travels with Charly after all.

Finally. What about vacation for yourself. With all of your travels is a vacation just impossible for you?

I go on vacations with my wife or kids to such lovely places as the Maine coast or to Madrid to look at the Prado. Last year I went on a cruise. Vacations are usually enjoyable, which translates as “nothing to write home about.” |

Thanks for sharing this fascinating interchange with Theroux. One of my favorite questions was when will he write about his travels in the US? To which he responds, “Maybe I’ll write Travels with Charly after all.” And yet several years ago he did write about the US in “Deep South” where the influence of his Peace Corps comes through. To begin with, he chooses one of the poorest more isolated parts of the country which resembles many of the developing countries he’s written about over the years (an so much for “American Exceptionalism”). He drives his own car and set his own agenda (as he did in writing his most recent book, “On the Plain of Snakes–A Mexican Journey”. And he interviews the locals off the beaten path—fairly normal workers/residents.

In regards to “Deep South”, I’d like to see Theroux consider a similar trip through the Southwest–Arizona has some historic levels of racism and biases with the Hispanic and Native American populations Theroux unique approach, research and grass root travel would reveal.

Although I’ve read several of his African based novels, like “Dark Star Safari”, I didn’t realize the impact Africa had on his work–thank you for posting this interview. Cheers, Mark

This brings back a lot of dusty memories of when we all were PCVs in the early 1960s, in what then was the British Nyasaland Protectorate, a part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. And a few conversations with Paul, which i still remember.

Like many former volunteers, I share a lot of Paul’s disappointment, about where most of SubSaharan Africa has gone the past half ceturry of post-colonial self-rule. Many governments subsisting on regular infusions of aid to keep basic government functions going, and with NGOs and European and American religious orders permanently in charge of things like hospitals and schools. A political culture of permanent dependence — forestalling a withdrawal to a culture of subsistence agriculture, and permanent pressure to migrate to somewhere else. .A lot of us pre-independence volunteers could, with some apprehension, see what was coming. Paul was not one of them, which may have exaggerated his disappointment. I can only point to present-day Zimbabwe, previously Southern Rhodesia, which, once the breadbasket of southern Africa, now hardly exists except in name.

What MIGHT colonial Africa have been ? Over the years I’ve mused about that. If independence had been anticipated much earlier, and political adjustments made (with the several indigenous African tribes, Indians, and various European populations (some of which had been there for 300 years), the past half-century might have been a very different story. A lot of us former volunteers could also see why that idealistic outcome could never come about.

The 21st Century, however, with a resource-hungry China and increasingly land-desperate southern Asian populations, eyeing the vast empty spaces of eastern and central Africa, this very likely will define the future of much of Africa.

Thanks, John, for reposting this 2002 interview. John Turnbulll

Commenting on the above statement by Mr Walker . His basis for opinion on those of us who call the Southwest our home I haven’t any idea.

I’m from multicultural, multilingual New Mexico, bilingual, with a foot in two Southwestern cultures, and friends in all our other, Indian, societies and pueblos,

I think the LAST thing we need is Paul T interpreting our lives and interactions for us. For the large inmigrating cities in Arizona, perhaps,, but NOT the rural Southwest, please. John Turnbull Lower Canoncito, New Mexico