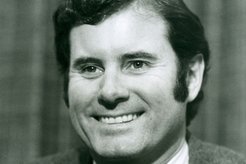

Talking with P. David Searles (Philippines & Peace Corps/HQ)

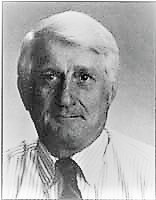

David Searles’ career has included periods during which he worked in international business, government service and education. After service in the United States Marine Corps (1955-58) Searles worked in consumer goods marketing and in general management positions in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada and Latin America. His business career was interrupted by a brief stint as a high school teacher (1969-71) and longer periods of service with the Peace Corps (1971-76) and the National Endowment for the Arts (1976-1980).

Searles served three years as the country director for the Peace Corps in the Philippines, and two years at Peace Corps headquarters as a Regional Director for North Africa, Near East, Asia, and Pacific (NANEAP) and as Deputy Director under John Dellenback.

Following the end of his business career in 1990 Searles earned a Ph. D. from the university of Kentucky (1993), and published two books: A College For Appalachia (1995) and The Peace Corps Experience (1997), both by The University Press of Kentucky.

I first interviewed and published David’s Interview in May, 1997

Talking with David Searles

In 1996 when I was working again for the Peace Corps in Washington, D.C., David Searles walked into my office. I had never met the man, but the Peace Corps Liberian, (the Peace Corps had a library then) Terry Cappuccilli, hold him that he should speak to me “about books.” David was digging through old files as he researched The Peace Corps Experience: Challenge and Change, 1969-1976, a book he was writing for the University Press of Kentucky. We talked mostly about the Peace Corps in the 1970’s, a period that years ago I began to call “the lost Peace Corps decade.” It was a time when the Peace Corps was merged into one large “volunteer agency” called ACTION. In my opinion, no other event did more to wipe out the Peace Corps from the minds of Americans. The Peace Corps uniqueness was lost. It became simply another U.S. government “alphabet” agency.

I was very glad to learn that someone was writing about “the lost decade” as most of the histories of the agency had focused on its creation and first few years Searles had been a Peace Corps staff member in D.C., a country director in the Philippines, and later regional director of North Africa, Near East, Asia and Pacific Regions (NANEAP) and deputy director in Washington. Now armed with a Ph.D., he could write about this decade from a historical perspective.

In February, when his book was published, I called the author in Kentucky, and we started to talk about the Peace Corps again.

How does the idea of a “lost decade” strike you?

D.S. I think that it is an excellent characterization of the way many Peace Corps people look at those years. One of the things I want to accomplish with the book is to restore that time to the record. It is important to do this because the Peace Corps really wasn’t “lost” where it counts the most: in host countries and in the lives of Volunteers. The tens of thousands who served in the 1970’s, and their stories, deserve a place in the agency’s institutional history. In addition, as the book demonstrates, a number of the crucial decisions which shaped today’s Peace Corps were made then, even though their origins are now forgotten. Just as the “lost generation” produced some great books, the “lost decade” helped make the Peace Corps what it is today, and I want to tell that story.

How did you manage to get a book published about the Peace Corps, and on such a limited period of Peace Corps history?

D.S. A good part was luck and timing. When the Peace Corps subject first came up, the University Press had just hired new editors who wanted to expand beyond the regional and local-interest subjects that had previously dominated its list. The Peace Corps as a subject was quickly endorsed. The press did not want “war stories”; they wanted the book to make a point. The fact that my point challenged accepted orthodoxy was a positive things, but not essential.

Why did you write this book?

D.S. I received my Ph.D. in 1993 from the University of Kentucky and my dissertation became A College For Appalachia, the first of my two books published by the University Press. I was interested in the Peace Corps as a subject because of my own experiences, but it didn’t quite fit in with what I was studying—the history of education—so I didn’t do anything with it in graduate school.

But as we know, the Peace Corps experience is truly unique. Its effect is powerful, long-lasting, and, for most of us, good. One day I was explaining this to a member of the press’s board of directors. She told the editor about the conversation, the editor called me, expressed interest in a Peace Corps book, and I went to work. I soon realized that the Peace Corps story is largely untold. Few books have been written about any period other than the early years, and many of those were personal memoirs rather than institutional histories. As I read the literature I saw that the 1969-1976 period, to the extent it was discussed at all, was badly misinterpreted. Because that was my time, and because I felt that I knew the real story, it became the focal point of the book.

I soon discovered that writing any history of the Peace without the so-called “war stories” was like making an apple pie without the apples. To be accurate, the book had to include the personal as well as the institutional. That led me to make contact with Volunteers from the 70’s, drawing out their recollections and weaving those stories into the body of the book. If I have been successful, the book will give historians a new perspective on the agency, but it will also delight anyone who has served in the Peace Corps—or anyone who wants to understand it—because it tells the story as it should be told.

Did you interview Shriver or Jack Hood Vaughn?

D.S. I did not talk with either. First, the published and archival material available for 1961-68 is so extensive, and their views so thoroughly covered, I concluded that nothing new would result and that research time could be better spent elsewhere. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, I wanted to book to draw attention to the period “after the beginning,” and not get bogged down yet again in the oft-told-tale.

Coming to Washington in the Nixon years, were you a political appointee?

D.S. Although I was a fervent Kennedy supporter in 1960, I made it a point of principle never to register as a Democrat or a Republican. When I was recruited for the Peace Corps, I said that I had always registered as an independent. What struck me most at the time was how carefully my interviewers avoided the whole subject. If the political clearance folks tried—and I don’t know if they did—that would have been hard pressed to find anyone in my entire universe who thought I was anything other than a liberal, if not actually pink-tinged.

When I made hiring decisions as a regional director and as deputy director it never entered my mind to ask a candidate such an irrelevant question as “Are you a Republican?” nor did my immediate bosses request that I do so. I am not so innocent as to think that no one ever asked such questions. I am living proof that one could be very successful in the Peace Corps of that time without Republican connections. Obviously this is not to say that there were few Republicans in the organization; after all, they had won the election.

Did the name ACTION come about because Joe Blatchford, then the director of the Peace Corps, had established Acción in the early 1960s.

D.S. I don’t know if there is a direct name connection between Blatchford’s Acción and ACTION, but it seems that it could not have been a total coincidence. The public reasons given for ACTION’s creation were that it would bring together federal programs of similar character and objectives (i.e. government-supported volunteer activities, both domestic and international), leading to economies of scale, cross-fertilization of ideas, and greater overall effectiveness. Searles’ book shows that, in fact, the similarities were few.)

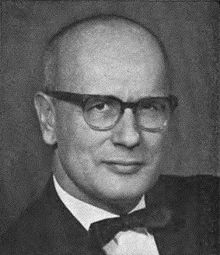

John Dellenback, a congressman at the time the law was passed, said that he supported the move for those reasons. Later, he changed his mind. Shriver’s was one of the few voices raised against the idea, along with those of VISTA volunteers and staff. Many Peace Corps loyalists accepted the creation of ACTION because they thought it would provide cover for Peace Corps from the “Peace Corps haters” in the administration.

There probably was also a hidden agenda. The administration wanted to do a trial run of its grand plan for the federal government. The creation of ACTION would help them learn how best to do the larger job while keeping the political cost of problems small. But that’s only speculation on my part.

You write a lot about the infighting between ACTION and the Peace Corps during the 1970’s. And we heard a lot about it at the time. How were you involved?

D.S. I was in the Philippines from mid-1970 until mid-1974 and cannot speak first-hand about those years in Washington. However, my impression—based on research I did for the book—is that there were several points of tension. The constant carping from the old hands about “New Directions” [Blatchford’s paper outlining his planned policy changes for the Peace Corps] was one. The near-death experience of the 1972 budget struggle was another. The consolidation of Peace Corps into ACTION was yet another, especially after Blatchford left and Mike Balzano arrived as director of the agency in 1973.

From mid-1974 until mid-1976, when I was at PC/W, the infighting was intense, but it was not within the Peace Corps. It was between ACTION and Peace Corps, and it was a daily part of life. Much of the problem resulted from the fact that the components parts of ACTION were so different that they had virtually nothing in common. There was, as well, a nasty management/union struggle—regularly reported in the press—during much of the 70’s. Other causes were Peace Corps’ superiority complex—which we thought soundly base, but which others found hard to take—and there was a clash of egos between those who had won their spurs abroad and those for whom the possession of a passport was a new thrill.

John Dellenback’s arrival as director in mid-1975 helped calm things down, but the only real answer was a divorce, and that was not to come for several more years. Interestingly, the problems between Peace Corps and ACTION continued, and even got worse, after a whole new crowd of players on both sides came in with the Carter administration in 1977. So, even though it is tempting to blame specific individuals, the problems were probably as much systemic as they were personal.

When I returned to Washington in summer, 1974 I became NANEAP director, a job that I had for a year. In mid-1975 John Dellenback asked me to become his deputy, an offer I accepted with pleasure because he was both a fine man and an excellent Peace Corps director. I must admit, however, that I’ve always looked at my Washington assignment as a penance for having had such a great time as a country director. After being in the field there was really little to be said for the life of a desk-bound administrator. (Like everyone else who had the opportunity, I spent a good part of my two years as a Washington staff member on the road, traveling to those parts of the Peace Corps world that were still new to me.) As mid-1976 approached. Dellenback asked that I extend for the sixth year permitted under certain circumstances by the five-year rule as that time. I agreed, but quickly learned from a well-placed source that “hell would freeze over” before ACTION management would permit it. So, I did as all Peace Corps folks eventually do—I started looking for a job.

Is there a place for the Peace Corps in 2000 and beyond?

D.S. There certainly should be.

Sometimes Peace Corps thinks of itself as unique in American history, an activity without the built-in support of traditional institutions. Yet our national history includes many instances where Americans have gone off to “do good.” The westward expansion was followed by a second wave of Americans intent upon bringing “civilization” to the new territories. Missionaries went to Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Americans of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries went to the Philippines to teach, to the urban slums to found the settlement house movement; others spent their lives in the rugged hills of Appalachia, and yet others taught the freed slaves in the South. The civil rights movement attracted thousands of people who devoted months and years of their lives to the cause. That aspect of the American character which has supported these varied efforts is the same one that supports the Peace Corps.

What incident sums up the Peace Corps experience for you?

D.S. Two Philippines Volunteers on vacation found themselves stranded in a small Malaysian town when their train was halted by storms and floods. They could not speak the language, had no local currency—they had expected only to pass through Malaysia enroute to the airport in Singapore—and without food and lodging, were in desperate straits. Then a stranger discovered that they were Peace Corps Volunteers. He explained that several years earlier a Volunteer had come to this same town, organized the construction and staffing of the area’s first hospital, encouraged the man speaking to continue his education, and won his town’s eternal gratitude. For the Malaysian, helping the stranded Volunteers was his way of paying back a bit of the debt he and the town felt that they owed that fondly remembered Volunteer. Here are the fruits of “promoting world peace and friendship.” And amply evidence that all three of the Peace Corps goals were accomplished in this tiny spot on the map half way around the world from Washington.

I am indebted to you, John, Marian and David. He posted a simple message on this site about seven years ago: “We need a PC timeline” which I took as an e-dare. Soon, David and I were exchanging personal emails. He read and commented upon a preliminary idea and an outline. Later, he commented on the draft book and finally, was kind enough to write a foreword for Peace Corps Chronology: 1961-2010. Of course, none of this would have been possible without Peace Corps Worldwide.

Good Heavens! I had forgotten much of this. John, thanks for t

he trip down memory lane.

David,

I knew you were not a RPCV and that governed my first reaction to learning you had written a book about the “Peace Corps Experience”, I must apologize. Your book is so valuable. It is so well documented and your analysis of Peace Corps history and the “distance” between PC/HQ and the host countries is so good. Thank you.

I guess I better read it Joanne Roll if YOU SAY SO in your peerless explain-English. So much is nowadays merely just a kind of Notification-Negotiation THAT drifts down into some propaganda related mendacity masquerading at its most innocent as prisms of curious ALPHABETS starved of any authenticity presented as baby-cat mewing. Ed

Joanne, WOW! You just made my day (week, Month. year?). Thanks very much. Now I’m going to show your comment to my wife.

David

Dave, You were director when I was a volunteer in Baguio City from 1971-1975. I married a Filipina in 72 and we are now retired and living on Mesa Arizona. Have your book along with some other PC books. Best wishes to you. Bill Powell

And besides owing a huge debt of gratitude to David, John, and Marian, we also owe it to you, Lawrence! Your Chronology is an invaluable tool as we are working to pull together the PC history for our documentary! Thank you to all of our Peace Corps historians!

Thank you for mentioning my thin chronology. It is good to know that my hobby served others well.

Hello David, I am hoping this conversation is still alive, and that you are well. You may or may not remember me, a PCV in the Philippines from 1972-74. I have just been rereading your book, “The Peace Corps Experience” and I am recalling my own experiences during those years. Life changing? Absolutely! As well as memorable and a source of great personal satisfaction for me, these forty plus years later. I may some day write of my own story, although the details of my service in the Peace Corps are growing dimmer with each year. Regards, Alan

Hello – I am not a Peace Corps Volunteer but I have read David Searles book many times. I am married to an RPCV Alvin J. Hower (PC/Philippines 1969-1974) and wanted to acquire a better understanding of the Agency that so captivated my husband, who considers his PC stint the best five and half years of his life. Thank you, David. The book increased exponentially my appreciation for the Peace Corps.

Is there anything being done to celebrate the 60th year anniversary of Peace Corps in March 1, 2021?

Hi David – I was really surprised in reading this interview that you used Paul and my experience in Malaysia as an important example of how Peace Corps really worked in the world. Thank you for that!

We have continued to have interesting experiences and have now been married for 50 years – married in Paco Park, Manila in 1975. We have retired to Portugal and still own a house in Maryland so we travel back and forth often.

After our Peace Corps tours we traveled overland from Kathmandu, Nepal to Brussels, Belgium, traveling through Nepal, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran, Turkey and on to Europe, flying back to NY from England.

I worked for the UNFAO in Rome for two consultancies, and then in Malaysia for one year. I also wrote a book for Peace Corps ICE program, Freshwater Fish Pond Culture and Management, which was used in aquaculture training for PC for years. We lived on the island of St. Croix, US Virgin Islands for 15 years, then retired to Portugal. We are right now in Chestertown, Maryland and just last week had lunch with John and Paula Wolflin, PCVs in Baguio when we were there too. It was fun catching up with them and made my thoughts turn to PC Philippines. I recalled that you were writing a book about the Peace Corps so I looked you up and found the above interview!

I hope you are well and still enjoying life! I want to thank you belatedly for helping bring Paul to the Philippines as a PCV. But that is another story.

Sincerely,

Marilyn Shook Chakroff

PS I just bought your book on Amazon.