Sixth Prize Peace Corps Fund Award: “Hyena Man” by Jeanne D’Haem (Somalia)

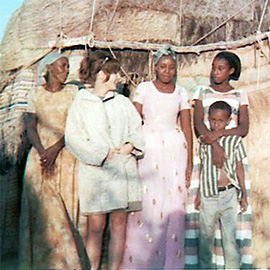

Jeanne D’Haem – 1968

Jeanne D’Haem, Ph.D. (Somalia 1968-70) is currently an associate professor of Special Education and Counselling at William Paterson University in New Jersey. She was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Somalia. She served as an English and math teacher in Arabsiyo and Hargeisa, and taught adult education classes and sponsored the first Girl Guide troop in Hargeisa.

Jeanne was a director of special services and a special education teacher for over thirty years. As a writer, she has published two prize-winning books and numerous journal articles. The Last Camel, (1997) published by The Red Sea Press won the Peace Corps Paul Cowan Peace Corps Writers Award for nonfiction. Desert Dawn with Waris Dirie (2001) has been translated into more than twenty languages. It was on the best seller list in Germany for over a year where it was awarded the Corine Prize for nonfiction. Her most recent book is Inclusion: The Dream and the Reality in Special Education.

•

Hyena Man

by Jeanne D’Haem

THE ETHIOPIAN CITY OF HARAR was once the capital of a mighty people. It was the first permanent settlement in Eastern Africa, a center of trade routes in the Arabian Peninsula, and is the fourth holiest city of Islam. In 1854, the British explorer, Richard Burton, became intrigued by this ancient capital and was determined to visit the walled city. No European had attempted the journey due to tribal warfare and reports that the emir would kill any foreigner who entered. British officials in Aden warned Burton “the human head once struck off does not re-grow like a rose.” Undaunted, he disguised himself as a Muslim and traveled through Northern Somalia to Harar.

After they entered the city, Burton threw off his disguise and announced that he was an Englishman, much to the horror of his companions. He was not killed, but was detained by the sultan who was impressed by Burton’s knowledge of the Koran. After ten days Burton was allowed to leave with gifts and supplies.

While in Somalia I read his book about these adventures, First Footsteps in East Africa, over and over. There were only a few books at my Peace Corps post, and mainly I was baffled by the Somalis.

I taught standards five and six in Arabsiyo, a small village in northern Somalia, now call Somaliland. Unlike Richard Burton who had no doubts, I struggled to understand the Somali perspective; it eluded me like the lovely gazelle that grazed near the wells.

First Footsteps was one of the few books ever written about the Horn of Africa and it was still the only description of the journey from Somalia to Ethiopia. The country and the scenes of Somali life that Burton described had not changed. After living for six months in the Horn of Africa, it seemed that time didn’t move forward, but back and forth like the camels on their treks between the grasses and the tribal watering holes. Village people were born, they grew old and died. Sand blew over the rocks covering their graves and carried their view of the world into the eyes of the babies on the backs of the women.

MORE THAN A CENTURY LATER, I traced Burton’s route from Somalia into Ethiopia during the school vacation from my post. I planned the trip to Harar with a Peace Corps friend, Terry, for a vacation. We decided our trip would follow the ancient salt road. Somali traders still harvested salt from the Indian Ocean and traded it in Harar for khat and other small items. Terry and I were excited to see more of East Africa, but I heard nothing but negative comments about my vacation plans from the Somali teachers at my school.

“Why do you want to go to Ethiopia?” Subti asked. The long tribal scar along the side of his face disguised his facility with English and interest in foreigners. He was my best friend and often kept me out of trouble.

“Just to see it,” I replied.

“What are you looking for? A lot of people here think you are a spy; this will prove it to them.” The Somalis dispute the boundaries of their country established by the British-brokered Anglo-Ethiopian Treaty of 1954. Somalia nomads herded their camels to traditional grazing lands within a few miles of Harar, and still populate most of the Ogaden on the Ethiopian side of the border. There were frequent armed skirmishes in the disputed territory and some of the village people assumed I would not go into this dangerous territory unless I had secret business with the Ethiopians.

“I’m not looking for anything,” I told Subti. “It’s there, I want to see it. Somali’s are nomadic — don’t you like to travel?”

“No!” he laughed with feigned exasperation at my endless stupidity about Somali ways. “We hate to travel. It’s a lot of work and you don’t know what trouble you might encounter — there are many hyenas in Harar.” When Burton set out from Somalia for Harar, the villagers recited the Fatihah, consoling him with the information that he was a dead man.

Terry arranged a ride to Tug Wajale, an outpost on the border with Ethiopia, with a friend from Borama, a police captain. “Why are you going to Ethiopia?” Abdul Abdillahi asked me as we bounced over the rough tracks that wandered around thorn bushes on the way to the border.

“For a vacation,” I responded, savoring the word and the thought of something other than goat milk for dinner.

“These Somalis, we don’t have a vacation,” he replied somberly, with a trace of moral superiority. Profoundly practical, itinerant people understand that travel is work; staying somewhere with both lovely grasses and water would be sweeter. Abdul wanted to know more in order to increase his feelings of superiority. “What will you do on this vacation?” he asked as he maneuvered the straining Land Rover over a dry riverbed and up the other side of the sandy bank.

“Oh, see new things, meet different people,” I replied, anxious to explain the American way of doing things. Terry just stared out at the peacefully rolling desert, unlike me, he didn’t need to justify his actions. The sky began where the land ended, a dome sealing out the winds of change.

“Those Ethiopians might think you are a spy.” Abdul offered ominously.

“What would we spy on?” I asked, careful to hide a touch of contempt. I couldn’t see what there was in Somalia worth spying on, much less fighting over.

“It doesn’t matter what you do, what people think you do is important,” he said, forgetting the road and looking at me until the jeep lurched over a rock.

Abdul dropped us off at the end of the tire ruts in a dusty field where trucks and Land Rovers stopped, some of them forever. Skeletons of vehicles baked in the burning African sun, already robbed of anything that could be scavenged. Black vultures circled effortlessly overhead, riding updrafts in the cobalt blue sky. We carried our suitcases past a mound of stones that marked a Somali grave, to the border crossing post — a dilapidated wooden shack standing guard over a dry riverbed. There was a footbridge over the arid gully, which looked so rickety I preferred to walk across the sand. However, I suspected that would have insulted the three border guards in tattered shirts who had been roused from their game of shahh. They jumped up and shouted at each other, as if they had been attacked, then quickly turned on Terry and me. I suppose we had startled them, it looked as though they’d been playing shahh for weeks.

All three men shook their walking sticks at us and blurted out curt commands until Terry and I were properly surrounded. Then, keeping a fearful distance, they marched us around to the back of the little shack with persistent exhortations lest we dare to disappear. They gestured that we should go inside, and one poked me when I did not move fast enough to suit him. I turned on my heel, and shouted, “Hey, just tell us where to go!”

Terry grabbed my arm and hissed, “Stop it,” he knew they would love a fight to break up the monotonous morning. If we were going to cross the border, we would have to do it the Somali way.

The weathered door had no handle and was holding onto the frame with bits of wire, but inside we were out of the blinding sun. An elegant Somali sat perfectly erect on a bent brown folding chair; his bony shoulders supported a long neck and perfectly oval head. He looked slightly surprised when we entered, then annoyed at the audience outside leaning on their walking sticks. They wanted to see how he would deal with the foreign spies; if he did not pass the test, they would comment later.

I felt like I had been arrested. “Pass-se-ports,” he demanded, as he thrust his chin out and stared at me. It sounded like the only English word he knew. Sensing weaker prey, he ignored Terry. I reluctantly handed over my smooth, green pamphlet. He opened it from the back and tediously began to thumb through the pages with long fingers. He was better dressed than the guards outside and had an embroidered shawl draped around his shoulders. I suspected that his real job was to extract hush money from the illegal khat traders who carried the narcotic green leaves from Ethiopia into Somalia.

The clerk looked intently at each blank page and then up at me as if I should explain why there was nothing on it. I pretended I didn’t know he had never seen a passport before, and wouldn’t know how to read one anyway.

Finally, his long fingers turned to the page with my picture on it and his eyes lit up. At last, there was something he could understand. He turned the little book around so it was right side up, held it up to my face, and compared the photo with my features. I was hopeful that we were making progress for a moment and smiled, but the long corners of his mouth slowly turned down into a deep and determined frown. The most official was not happy. He looked from the photo to me several times. He squinted and scowled. I feared for the worst and bit my lip. Finally, he slammed the book down on the rickety table that almost collapsed on its spindly metal legs. Holding me prisoner with his eyes, he twisted his arm around and reached toward a battered metal filing cabinet. He managed to jerk the bottom drawer open despite the fact that it was absolutely stuffed with musty papers. He pulled out a fat sheaf of crumpled documents, put them on the table, and began to examine them. The most exalted executive of the border shack, looked from me, to the mangled pieces of paper, to my passport, and back at me again. He slammed his fist down on the table again and I jumped. The little crowd outside murmured their appreciation. The white woman winced!

I was more and more certain that we would be detained for several months while he scrutinized each paper to see if I were an international criminal. I looked around at Terry who was sitting back in the only other chair, but he avoided my gaze. Voltaire once said, “Oh Lord, make my enemies ridiculous.” God had granted it.

Fortunately, Abdul Abdillahi came round to see what had happened to us. He and the clerk went outside to talk, leaving me to ponder my fate with the little pile of papers. They were in Arabic and I surmised they might be left over from Koranic School. I couldn’t imagine what they had to do with the border or where the petty official had managed to collect so many pieces of paper. Foreigners probably never crossed this border outpost and the Somali nomads who wandered across the border didn’t have passports.

Suddenly I was desperate to get away from the flies, the dust, and the taste of weevils in the flour and the constant irritations of life in Somalia. Everything was ramshackle, broken, patched and worn out from over-use. A sleek new bus waited on the other side of the border, a small white plume of exhaust emanated from its tailpipe. It was so close I could hear its motor purring softly. It might even have air conditioning! However, that bus could have been in New York City.

When the official returned he was quiet and sulky. He sat bolt upright in his seat and folded his hands in front of him like a judge. He looked carefully in my face and studied it for a moment. Then he cleared his throat and asked me my name, in Somali.

“Muga, I goo wa Jeanne,” I replied.

“What is your tribe?” he asked, the Somali equivalent of your address and occupation. It occurred to me that Abdul might have warned the imperious man that I was not without connections.

“Sa’ad Musa,” I told him without hesitation. Members of my little village had adopted me and declared me an honorary member of the Sa’ad Musa tribe.

With this announcement, my tormentor burst into a wide grin, revealing missing teeth on both sides of his mouth. If I stole something or drew blood in a fight, his relatives could extract payment from my clan. If he were to interfere with my business, members of my clan could demand retribution from his. Satisfied, he reached into a battered goat-hide pouch kept on the dirt floor beside the tormented table and removed a stamp and ink pad. With immense concentration, he carefully inked the stamp. It was as big as an entire page in my passport. Why is it that the smaller the country, the bigger the stamp, and the more officious the stamper. He finally inked the stamp to his satisfaction and thumbed through my passport until he found a page he liked. He eased the stamp onto the page and rocked it back and forth several times for maximum coverage. He turned the little book around to study his great stamp from every angle. Satisfied, he handed it back to me with a flourish and a shy smile. I obediently admired the stamp and thanked him profusely. Terry handed over his passport, and my new kinsman stamped it firmly and handed it right back. Our officious official motioned that we should pass but at that point, I knew the teachers were right. In Africa, travel is usually uncertain, often dangerous and always work.

A ragged gang of little boys waited outside the little shack with the border guards and several curious women. They had heard some faranioch were being detained and had gathered to watch the fun. They picked up stones and hurled them at us as we walked toward the border. I hated the little pebbles that fell around my feet at every step. Emboldened by the fact that we were leaving the country, the boys began to aim higher. A stone hit my back, another my shoulder. I was burning with rage and turned as if to take after them. They retreated a little way and I turned back toward the border. Another stone hit my shoulder.

“Bisass! (Spy),” they shouted. One belligerent bag of bones with a filthy shirt and no shoes stood right on the bridge and taunted us, holding a large stone and threatening to throw it in my face. Shaking from fear and anger, I was ready to turn back and admit there were no vacations in Somalia.

Suddenly a large shadow loomed, and the boy turned in surprise and looked up at a tall Ethiopian soldier. He was wearing a uniform, complete with a gun belt, tan shorts and a perfectly pressed white shirt with epaulets. The insolent little ruffian held his miserable stone up defiantly and shook it at the perfectly composed soldier. The tall one gazed down at the intransigent child as if he were a pesky chicken.

WE WERE PROCESSED into Ethiopia in a building with an electric fan. The uniformed official carried my bag and helped us onto the bus. He assured me in perfect English that we would travel a hundred miles to Harar within three hours. The bus smelled new; there were no squawking chickens or hysterical goats tied on the top. I fell back into the comfort of the upholstered seat and relaxed for the first time. I joined the Peace Corps and went to Africa to change the world, to bring peace and understanding, now I really only wanted to sit on a cushion.

Twenty miles from the border, the desert shrubs and flat topped acacia trees that pocked the land in Somalia gave way to coarse savanna grasses. Gradually the countryside turned from desiccated brown to variations of green. As we approached Harar, fields of cotton and sugar cane surrounded the road. Orchards of lemon and pomegranate trees snuggled in sleepy lanes. Farmers, herding fat cattle, walked next to the road, driving the beasts to market.

The high walls that surround Harar were visible from about two miles away. Burton was disappointed when he first saw the town and so was I. It was not a glittering medieval city. It was rather gray and flat with a few minarets poking out of an undistinguished pile of stones. The tallest spire was the Abyssinian church, the most remarkable building in the city. The air was cooler than in Somalia because the city is at 6,000 feet above sea level and rain clouds blocked the sun. With 60,000 inhabitants it was the biggest city I had seen in months.

Our bus dropped us at one of the five large gates to the city. We walked up a narrow lane of two story houses decorated with hanging bananas, and women strolled back from the market on paving stones worn smooth by a century of passing feet. The flat-roofed houses were built of rock quarried from the neighboring hills. Latticed balconies overlooked the street. It was calm and peaceful like other African markets I had visited. Terry and I went up and down several winding lanes to find our hotel located near the governor’s palace. Our room had running water and I felt like I was in the twentieth century again until I noticed the cockroaches on the bottom of the bathtub.

That night, at a dinner of roasted goat and spiced rice, a young man came over to our table and introduced himself. Ali Hussein explained that he had worked for USAID in Hargesia for several years and was visited his family here in Harar. He had the perfectly proportioned Arabic facial features — the oval face, small nose and rose lips on a slender body mostly composed of arms and legs. Ali was eager to talk and full of information. “The gates of the city are locked after sunset,” he explained. “It’s to keep out the hyenas,” he explained. “They will carry off small children.”

“Really.” I scoffed. It sounded more like a rumor than actual fact. “Hyenas almost never eat humans,”

“That’s true,” said Terry, “but hyena bites are deadly because their mouths are full of infectious bacteria from the rotten meat they eat.”

Ali Hussein agreed, nodding his head. “Those wild animals are a big problem — they are not afraid of anything — least of all people. They will follow you right down the street.” Burton mentioned the hyenas in his book. He too reported that they would devour anything, including men if they were hungry enough.

“But you have lots of soldiers. Don’t they take care of wild animals?” I asked.

“Soldiers are not concerned with animals,” Ali answered with a meaningful glance around the room. He offered to take us outside the walls of the city to see a man who actually fed a pack of hyenas with his bare hands. He explained that most people in Harar believed that if you feed the hyenas they will not bother the town. Terry didn’t think this excursion was such a good idea. He described how hyenas run alongside their prey and tear hunks of flesh from the stomach as it tries to escape. I was intrigued and understood why Burton insisted on coming to Harar despite the warnings he had received. He couldn’t remain safely disguised, and I couldn’t remain safely in my hotel room. I was drawn to danger like a moth to light. I wanted to see the untamed soul of Africa. I could feel it, I knew it was there; I wanted to get closer because somehow danger felt like truth.

The equatorial darkness settled suddenly over Harar, like a door closing. We followed Ali in the dim light offered by a half moon and a million stars through the streets of the city. Soft lamplight glowed in little rooms and children whimpered. Far away I could hear women weeping, I knew it was the death wail. A widow and her daughters were sitting outside and crying to Allah, proclaiming their misery and honoring the deceased by the volume of their howling.

Ali led us to one of the large, old, wooden gates, already closed for the night. Seeing our white faces, the gamekeeper swung it open with a wide toothless smile. I hurried past wondering why he was smiling.

Just outside the city walls, on a slight knoll overlooking a wide plain, I could see a circle of people standing just in front of some old rock walls. There were two cars with lanky Ethiopian men standing beside them. As we passed, I noticed veiled women inside the cars. The hyena man was cajoling a knot of men standing uneasily behind him. When we joined the group he began to tease the only foreigners.

“Mericans?” he questioned and pointed at us with a long accusing finger. When I nodded affirmatively, he laughed loudly and shouted “John Kennedy!” Several members of the crowd had flashlights and they shined them at us. The hyena man resumed his harangue and the beams turned in his direction. He was short and round. His pants were rolled to the knees to avoid the dust as he kneeled on the ground, but they were already dirty. He had thick, barrel arms, long frantic hair, and a wild look in his eyes. I couldn’t tell if it was fear or he was crazy. When a crowd large enough to suit him gathered, he hunkered down into the dust just two feet from where everyone was standing. He began to whistle and call loudly into the darkness of the open countryside.

My heart leaped when I saw the first pair of yellow-green eyes peering at us from the shadows. Then I saw another pair and another. I couldn’t count them because they were constantly on the move, but I knew there were at least twenty hyenas close by. The animals paced back and forth, occasionally lunging at each other, snarling and whimpering. The panic that slumbers in a small corner of my mind began to wake.

The hyena man reached into a large leather pouch and pulled out a hunk of rancid meat. He threw it out into the black night. We heard the animals scramble and pounce the instant it touched the ground. Howling and snarling they fought in the darkness. We could hear the snap of bones as they ate because they eat every part of an animal, grinding it up like a Cuisinart. My body tensed tighter with each yelp. I looked behind me to check out the location of the nearest car, and some measure of safety.

The hyena man tossed another piece of raw meat and the African night was alive with brawling. I thought I heard something behind me and jumped, not forward, certainly not forward. The hyena man saw me lurch and he shouted something in my direction, which amused the crowd. He took out a smelly lump of animal flesh and tossed it right where I was standing. I hadn’t fully grasped what he’d done when a giant, spotted dog rushed into the light. The animal stopped in front of me and was close enough to smell. The hyena was much bigger than I had thought, with powerful hind legs. One ear was still bleeding from a recent fight, and saliva dripped from enormous, fanged teeth. He kept his yellow eyes on me as he bent down on short front legs and his powerful jaws grabbed up the meat. I was too frightened to move and glad to feel Terry’s tense body right beside me. The hyena backed off, still watching me until he was far enough to turn and scurry away. The hyena would have to fight to keep what he had taken.

The hyena man howled to the beasts. He yelped and howled into the night, as wild as the beasts he teased. He tossed his putrid treats closer and closer. One by one the creatures came, slinking slyly through the starlight, snatching food from their tempter. Finally, the hyena man placed a piece of meat at the end of his bare foot. Slowly, one bold, spotted dog came forward and warily picked up his prize. The hyena man raised the stakes. He knelt on the ground and held the meat in his hand, yipping insanely. The darkness seemed full of caterwauling beasts and crazy men. Soon one desperate creature approached and was caught in the glare of automobile headlights suddenly turned on to illuminate the scene. Determined or blinded, he snatched the meat from the outstretched hand in his large incisors and nimbly trotted back to the bush.

The hyena man beckoned to me, come and feed them he motioned playfully, daring the white woman. When I refused, he threw a piece of meat right at my feet. Angry at his teasing, I held my ground. I began to feel slightly cocky. These animals looked like dogs, trained dogs. On cue, a spotted beast approached and claimed his prize. Then he smoothly retreated. So they are trained, I thought to myself as the crowd cheered in appreciation. I wondered why no one in the crown offered to flaunt their bravery by holding meat for the beasts.

The hyena man held a piece of meat in his mouth and began to snarl and nip like the dogs themselves, taunting the creatures to take it away from him. He shook and pranced like the animals and when powerful jaws locked around the meat he did not release it but snarled and fought. Undeterred, the hyena pulled back and they tugged back and forth until the more powerful player won and trotted off into the distance, his tail held high.

The hyena man offered the last bit of meat to the crowd. He beckoned to one man after another. None would take his place and I guessed he was insulting their manhood by the laughter. Shrugging his shoulders, he lay down on the ground and held a piece of meat over his head. I held my breath as one of the ugly animals sauntered into our light. He watched warily for several moments as his eyes adjusted. Then he carefully walked right between the hyena man’s splayed legs. One by one he put his front paws beside the man’s chest until he was standing over the prone body. His slashing teeth and powerful jaws were inches from the hyena man’s bare neck. He stretched forward and took the meat from the outstretched hand. I knelt and took a picture just as the hyena took the meat. Startled by the flash the beast snarled at me but he held his prize and carefully backed up. He disappeared into the night.

“Those hyenas are practically trained,” I remarked to Ali as we put a few shillings into the hyena man’s hat. “That last hyena looked almost tame.”

Ali shook his head, “I guess this was not so exciting tonight.”

“It was interesting, but after a while, those animals know what to do, they knew pretty much what to expect from the hyena man,” I explained. After all, I had a degree in psychology and had studied behavior modification and B.F. Skinner.

“But, that’s not the real hyena man,” Ali said.

“What?” I wondered how many people did this sort of thing. “Where’s the real hyena man?”

“He was killed last week by a hyena,” Ali said quietly. “The man we watched was his son.”

“Oh my God,” I muttered, breathless as we hurried to the city gate.

We needed to walk through many narrow streets back to our hotel. Harar was hushed, doors closed and windows shuttered. There was nowhere to go if an animal suddenly leapt out of the darkness. My heart beat wildly all the way back and my thoughts were racing. A book by a British explorer would not help me to understand Somalia. First Footsteps in East Africa was not a good guide. It had simply reinforced my own arrogant assumptions. Like Burton I had dismissed those who warned me about travel. I had derided the people at the border and the courage of the hyena man’s son. Proust said that the real voyage of discovery consists not in seeing new landscapes, but in having new eyes. With new eyes, I needed to approach Somalia respectfully, one step at a time.

A powerful experience and a reminder of the wonder of travels in Ethiopia. I visited Harar and Dira Dara in 1964 but my recollection of the hyena man was that he leaned over a low hanging balcony and the hyenas jumped up to snatch the meat. I saw hyenas on another occasion from the safety of a Land Rover with the head lights on. Volunteers in Mekelle reported seeing their barking dogs scare hyenas away and I heard stories of hyenas killing babies and sick people .

This is my favorite story among the Peace Corps Fund award winners you’ve published on the site so far. I don’t envy the contest judges! Myself I’d love it if you published all of the stories submitted. Thanks to Jeanne D’Haem for telling this one.

Thank you Jeanne! I met you at Terry’s house one Friday on an expedition into the bush with Yano. I remember Terry had a big sunflower planted in his back yard. We were so innocently idealistic, weren’t we?

To everybody else, this story is real. I lived the same adventure at about the same time, crossing into Ethiopia the same way, probably having read the same copy of Richard Burton in Hargeisa.