Review — UNDER CONSTRUCTION: TECHNOLOGIES OF DEVELOPMENT IN URBAN ETHIOPIA by Daniel Mains (Ethiopia)

Under Construction: Technologies of Development in Urban Ethiopia

Under Construction: Technologies of Development in Urban Ethiopia

By Daniel Mains (Ethiopia 1998-99)

Duke University Press

240 pages

September 2019

$24.65 (Kindle); $82.49 (Hardback); $25.95 (Paperback)

Reviewed by Janet Lee (Ethiopia 1974-76)

•

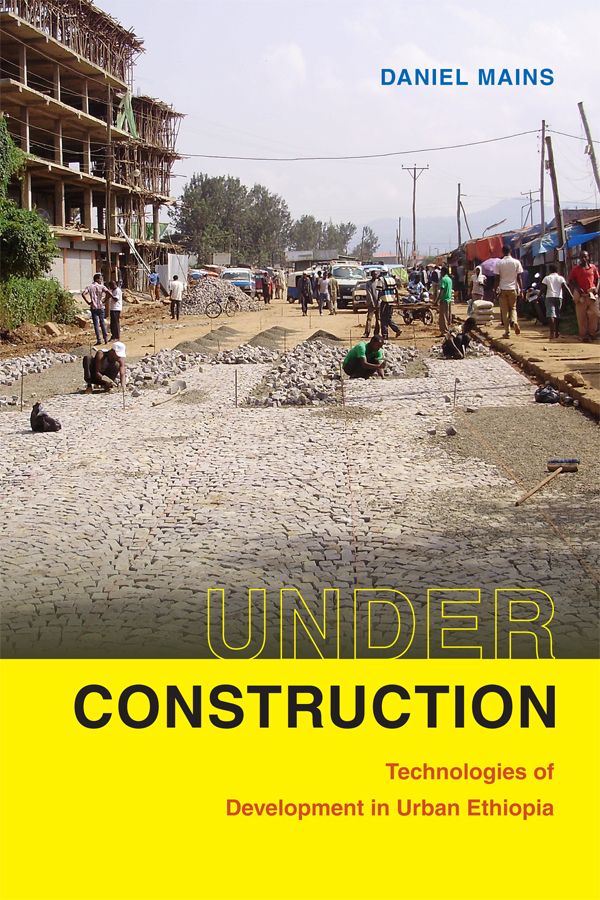

Under Construction is a scholarly work about the intersection of various forms of technological infrastructure in Ethiopia, the Ethiopian state that governs and develop the technologies, and the human element that service and should be served by the technologies. Construction projects in this study include dams, specifically GERD (the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam), Bajaj transportation, asphalt road construction, and paving stones. Under Construction is an apt title, because as the author details, these projects appear to be perpetually under construction.

Mains is Wick Cary Associate Professor of Anthropology and African Studies at the University of Oklahoma and the author of Hope is Cut: Youth, Unemployment, and the Future in Urban Ethiopia (2011), a fascinating culmination of his work studying youth in Jimma. He served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Goha Tsion, 1998-99. Elements of his Peace Corps Ethiopia service can be felt throughout as he moves from place to place in the communities he visits, walking or using local transportation, drinking endless cups of coffee, befriending and being befriended by the local residents, chatting, joking, soaking in the stories that give background to the analysis of the hopes and conflicts of modernization through technologies.

It is difficult not to insert myself into this review as it resonates so closely with my recent experience in Ethiopia as a Fulbright Scholar in Axum for ten months from 2017-18 where I was assigned to the Aksum University Library with significant time spent at the Axum Heritage Foundation Library. It was at the Foundation Library that I was able to directly observe and be involved in the construction of a new building. Daily walks to and from the library, dodging Bajaj traffic, tripping around potholes, and being grateful for newly laid stone, immersed me into the local culture. Reflections of my time in Axum are interspersed throughout.

Mains did his homework, researching and documenting construction projects in Ethiopia, in other parts of Africa, and in developing countries of the world, and presented a balanced viewpoint of the impact that these projects had on the local economies, the environment, and the livelihoods of the population of the areas studied. This was especially true in respect to the controversial topic of dams, in particular GERD (Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam), which is seen by some as modern and others as outdated technology, destructive rather than forward-thinking, the ultimate solution to economic stability at the cost of great human hardship.

He focused his fieldwork on construction projects in two settings: Jimma and Hawassa, Jimma being his primary residence while researching the lives of youth in the previously mentioned book, Hope is Cut. Hawassa was more cosmopolitan with tourist attractions and a myriad of NGOs. Jimma not so much, but attractive to him, nonetheless. He states, “More than anything, it is the people of Jimma that keep me coming back. Jimma residents seem to have a particular talent for chewata, the playful conversation that Ethiopians use to pass the time.”

The asphalt road projects had differing degrees of success in Hawassa and in Jimma. The number of asphalt roads built in Hawassa doubled between 2005 and 2015. Urban planners organized neighborhoods into large grids and the city attracted businesses from Addis Ababa, many that catered to those who worked for the many NGOs that utilized those roads. Success, if it could be called that, was more fleeting in Jimma due to issues with soil type, weather, ethnic politics, and mismanagement. Neighborhoods were resettled and social networks disrupted. Still most of the locals took the move and subsequent modernization in stride. Asphalt roads were being built all over the country, including the road leading into Axum, where I lived for ten months. It was named by the locals as the “China road” referring to the funding and construction company involved.

The more fascinating technology to me was that of roads built with cobblestones. Highly labor intensive, cobblestones build roads and lives, employing over 100,000 people to build 1,000 km of roads. Considering the youth unemployment rate has been about 50%, these jobs became all the more important in building the economy. Workers organized into associations and were managed at the city level. The workers were both owners and laborers and jointly shared in the profits. They utilized materials from local quarries, minimizing environmental impact. Young men and women gained important skills and also grew up in the process.

While I was in Axum, I watched as paving stones were placed on paths that led from both entrances to the various buildings on the compound. Chiseled local stones of various hues formed an intricate design on the front plaza leading to the main entrance of the new building, placed there by artisans with significant skills and pride in their craftmanship. Female hod carriers worked side by side with their male counterparts moving dirt, cement, stone, and debris from one pile to another. The city also had an extensive paving program, financed in large part by the businesses along the route. The Foundation Library was mandated to replace the existing stone in front of the compound, a significant expense even factoring in the reuse of the older stone within the grounds. The chapter in Under Construction on paving stones gave me an even greater appreciation of the importance of the cobblestone roads and walkways to the city and to the economy of Ethiopia as a whole.

It was not immediately apparent to me how driving a Bajaj could be considered construction, but Mains wove the operations and importance of this form of transportation into the study nicely. Although owned and operated privately, the state determined the routes, passenger fares, and the operating license. Owners typically leased out the vehicle to a driver who paid the owner a set fee, the remainder serving as profit and fuel expenses. The greater the number of passengers during the day, the greater the profits Like cobblestone work, the industry is labor intensive and employs a fleet of young men. A Bajaj provides four types of income: driver, owner, mechanic, and car washer. The industry also provides a service that cannot be provided by the city, specifically inexpensive transportation within a community, thus contributing significantly to the overall economy. There was a quote that I heard while traveling, “Things get done by God & Bajaj,” reflecting on the importance of the industry.

I became friends with several of Bajaj drivers, many who worked multiple jobs trying to make ends meet Other than the mini-buses that carried passengers from one town to another and tourist vehicles, the Bajaj was the main form of transportation apart from going “by foot.” I don’t recall seeing many, if any, vehicles used strictly for personal use. This study filled in the blanks missing in my own personal observations of life in a somewhat urban setting.

Mains did not visit GERD in person, it being physically distant and under heavy security. But as he points out its presence was felt everywhere in Ethiopia, the image on posters, Ethiopia telecom calling cards, and in the minds and hearts of the population. It became the symbol of modernity and state-led development. Due to the loss of outside funding, the government offered the sale of investment bonds to fund the project to Ethiopians citizens and those of Ethiopian ancestry in the Diaspora. The state also forced government employees to donate portions of their salaries to GERD as well as other projects such as the Jimma road construction.

These construction projects were a source of pride, but as his confidants revealed, a source of great tension. Through stories, humor, expressions of hope, and wails of despair, Mains’ contacts were candid with him, oft times using metaphors of kinship (step child/ye injera lij), bodily functions (empty stomachs), local climate (mud & dust) to describe their relationships to the government or in explanation of an ongoing project. Mains embedded himself within the community he researched and gained their trust. Each encounter with a shopkeeper, taxi driver, jebena coffee shop customer, city official, brick layer was an opportunity to get the lay of the land. Who among us has not sat in the office of a government official just to make an appointment with said government official?

Interspersed throughout are relevant references to historical events, from ancient kingdoms to the most recent change in leadership, insight into the Ethiopian psyche, and the effect these events had on the acceptance, either fully or with reservations, of these construction projects on Ethiopia’s road to modernity.

Daniel Mains is in the same league as the likes of Donald N. Levine and Theodore Vestal, great authors on Ethiopian culture and history. Like his previous title Hope is Cut, Under Construction provides insight into the life of modern-day Ethiopia. Both titles are well worth the read. You have my word on it.

•

Janet Lee (Ethiopia 1974-76) served in one of the final groups of PCVs in Ethiopia during the early 70s. After having visited Emdeber for the first time, she was in Addis Ababa the day that HIM Haile Selassie was overthrown and witnessed throngs of young men chanting in the streets. Since 2006 she has returned to Ethiopia six times for a variety of library and literacy projects including six months in Mekelle in 2010 and ten months in Axum in 2017-18 as a Fulbright Scholar. From 2012-17 she was content editor of The Herald: News for those who served with the Peace Corps in Eritrea and Ethiopia. She is Dean Emerita, Regis (Denver) University Library. She has edited several library-related publications and written and presented extensively about libraries and literacy in international settings. She is currently President, Ethiopia & Eritrea Returned Peace Corps Volunteers, an affiliate of the National Peace Corps Association.

No comments yet.

Add your comment