Review — THE BAD ANGEL BROTHERS by Paul Theroux (Malawi)

The Bad Angel Brothers

by Paul Theroux (Malawi 1963-65))

Mariner Books Publisher

352 pages

September 2022

$14.99 (Kindle); $26.09 (Hardcover), $22.35 or 1 credit (Audiobook)

Reviewed by Mark D. Walker (Guatemala 1971-73)

•

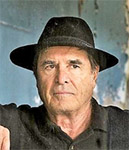

Paul Theroux

Paul Theroux (Malawi 1963-65) is probably the most prolific of the Returned Peace Corps writers, with 33 works in fiction and 53 books overall. As with his latest book, I wasn’t enthusiastic about reading it, as I prefer his nonfiction travel stories. But just as was the case reading the life of the aging surfer in Hawaii in Under the Wave of Waimae (2021), he does a stellar job developing the characters in this psychological thriller.

This most recent book is a classic tale of a dysfunctional family. A younger brother’s rivalry with his older brother, Frank, a domineering brother and a well-known lawyer in their small community in Massachusetts. Frank also has a propensity to come up with some vicious betrayals, which leads to the growing frustration and psychosis of his younger brother, Cal.

Andrew Ervin of the New York Times Book Review does an admirable job summing up the narrative:

Theroux soon takes us back to their shared childhood and the lifelong rivalry that led to such fratricidal ire. Cal grows up to be a metallurgist and a prospector “searching wild places for minerals and metals.” His escape from their stifling hometown first takes him to the American Southwest in search of solitude and, more importantly, gold. What he finds instead in the desert is a half-dead body. He’s able to nurse the man back to health and return him to his fortified Arizona compound, only to discover that he has rescued none other than Don Carlos, the patriarch of a Mexican cartel. For his efforts, Cal is accepted as an honorary member of la familia Zorrilla, a wealthy, and obviously powerful family.

As someone from the Southwest, I appreciated Theroux’s description of the impact of the desert’s vastness on Cal, “My being in the bosom of the wilderness granted me silence and self-reflection; my prospecting was a form of meditation. As the weeks and months passed, I became more and more suited to living in the austerity of rocks and stones and cactus, hardier than I’d ever been, but more than that, mentally strong…. It was a spiritual awakening in one sense, but with my feet on solid ground, on bedrock, far from Frank’s orbit.

Fortunately, the author takes Cal to mining operations in Australia, Central Africa, and Columbia for those who suffer from wanderlust. Theroux’s Peace Corps experience probably helped him describe the “paradox of serious travel:”

You go far but after a while, months rather than years, it wears off. Then all

is smooth in your life until you return to your hometown and are hit hard,

stunned anew. There is no recovering from it. The culture shock of arriving

home never leaves you—you long to escape it, to go away again soon.

The author does a masterful job describing one morbid scene in Africa where Cal is searching for precious ores:

It was a rectangular ditch at the periphery of the clearing, and the movement in the air just above it, like a skein of woodsmoke, were flies, whirring, gleaming, their blue bodies fattened by the light. We approached the buzzing hole, but when the breeze lifted, and the reek hit us, we drew back. Moyo leaned and looked in, holding his shirt to his face. I stepped behind him and saw a man crammed into the pit, almost filling it, because he was bloated, tightened against his clothes, swollen and stinking, his whole head covered with flies. “Congo,” Moyo said. We have arrived.

Cal’s character as a white savior is aptly described by Andrew Ervin, as well:

I didn’t fully loathe Cal’s white savior act until he returns to an emerald

mine he co-owns in Zambia and ogles a village woman while she’s

balancing laundry on her head. ‘I supposed like some colonizers—I was smitten,’ Call tells us. He hires the woman, Tutwa, as a servant and she soon

becomes his “junior wife,” making her, by my reckoning, the third person of

color whom he rescues from degraded conditions and who gratefully accepts

him as family. He ends their affair later by paying for her to go to nursing

school and start a new life. What a guy.

He met his wife-to-be and the other person of color in Colombia, where he worked for an emerald-mining operation. Vita is a half-Cuban woman he meets, falls in love with, and brings her home to Massachusetts, where they have a son. Vita becomes overdependent on the older brother, Frank, who provided pro-bono work for her charity to help children.

Much of the book’s narrative is a constant litany of complaints and resentment of Cal towards his older brother. And Theroux is at his best as he builds these tensions and resentments toward what Ervin calls the “inevitable homicidal rage.”

This growing resentment, boarding on becoming delusional, is reflected in this scene where Cal is in bed staring up at the ceiling of the deteriorating family home he has returned to:

Inspired by the stains (stains I regard as prophetic, omens to be seized and understood), I saw Frank as an infection. In my mind, I simplified him and made him small. He was teeth and claws; he was a greedy appetite; he was a yellow stain; he was a bad smell. He was not a person. I needed, for my sanity, to be rid of him so that I could go on living.

Cal’s frustration comes to the fore when his lawyer presents him with a bill of

$64,243 for litigation brought on by Frank. “I’m underwater, people say of their debt. It’s an accurate image: I was sinking and suffocating.”

I won’t give away the final scene, which makes the read worthwhile, only to say that the cartel leader whose life Cal saved would become an essential part of this story’s inevitable, violent end.

I agree with this summation on the inner flap of this book,

Few writers have as keen an eye for human nature as the inimitable Paul Theroux, and this riveting tale of adventure, betrayal and the true cost of family bonds is an unmissable new work from one of America’s most distinguished and beloved novelists.

•

Mark Walker

Mark D. Walker (Guatemala 1971-73) spent forty years working with international agencies and today is a contributing writer to Literary Traveler, Wanderlust, and Revue Magazine. He is also the author of Different Latitudes: My Life in the Peace Corps and Beyond, and My Saddest Pleasures: 50 Years on the Road. His wife and three children were born in Guatemala. His website is www.MillionMileWalker.

As a lover of Paul Theroux’s work I found the review tantalizing and am now thus more prone to the anticipatory pleasure of getting my copy in Japan…

Eric–

Sounds like we both admire Theroux’s work. I’ve read and reviewed the last seven books from the “Dean of Travel Writing” and was fortunate enough to obtain one of the early copies of this book. I wrote my latest book, My Saddest Pleasures: 50 Years on the Road, in honor and appreciation of Theroux and another travel writer, “who personally knew and were inspired by Moritz Thomsen and passed their enthusiasm on to me.” Thomsen wrote the Peace Corps experience classic, Living Poor: A Peace Corps Chronicle. Theroux’s book, The Tao of Travel, which celebrates 50 years of travel writing, inspired my series, “The Yin & Yang of Travel.”

Enjoy the read,

Mark