Review — AFRICA MEMOIR by Mark G. Wentling (Togo)

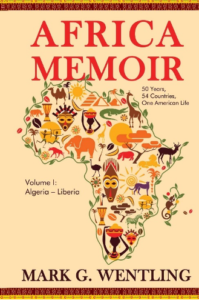

Africa Memoir

Africa Memoir

by Mark G. Wentling (Togo 1970-73)

Open Books Publisher

255 pages

August 2020

$9.99 (Kindle); $21.95 (Paperback

Reviewed by Robert E. Hamilton (Ethiopia; 1965-67)

•

To review fairly this first volume of three in the Africa Memoir trilogy, it will be generally useful to remember what it is, as a book and concept, rather than what it is not. It is not, for example, a history of the 54 countries in Africa, all of which Mark Wentling has visited (some only briefly). Neither is it a guide book which you would expect, like Lonely Planet or a Rick Steves publication, to be updated annually or regularly. Wentling says in his Foreword:

The central purpose of this book is to share my lifetime of firsthand experiences in Africa. I also attempt to communicate my views about the many facets of the challenges faced by each of Africa’s countries. At the same time, I provide some basic information about each country and some comparisons with the United States.

He does utilize “reference works” (e.g. Encyclopedia Britannica and CIA Fact Books) and offers “personal conclusions.” But, it is not a small-gauge scholarly, academic book. Rather, it targets a general readership rather than that of a narrow academic or development specialist audience.

The countries are presented alphabetically: Algeria-Zimbabwe. In a section titled “Africa’s Complexity,” Mark Wentling, who has spent 50 years living and working in Africa, notes that Africa comprises more than 25 percent of the United Nations membership, a population of 1.2 billion people. Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has “the world’s highest urbanization and population growth rate,” and 50% of the continent’s population is below the age of 19. By 2022, Africa will have more people than China or India. Geographically, Wentling reminds us, Africa is as large as the US, China, India, and Europe combined. Within its coastal boundaries, there are about 2,000 ethnic groups, demonstrating that the people within the cradle of humankind populated the various ecological zones of the continent and invented the technologies which made them successful hunters, gatherers, and fishers over the last 200,000 years. These original ancestors then expanded into the Middle East, Asia, and Europe. However, these explorations were, apparently, done in a pedestrian fashion overland, not as sailors. Africans learned to fish coastal waters, but until the invention of the lateen sail, employed in the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean first, long-distance sailing was not possible.

Not an historian, archaeologist, anthropologist, or paleo-biologist, Mark Wentling does not offer readers answers to questions found in, for example, Ghanaian-born Kwame Anthony Appiah’s 1992 book, In My Father’s House: Africa in the Philosophy of Culture (New York: Oxford University Press). In Chapter One, “The Invention of Africa,” Appiah addresses the question of whether there is something common to all of the 2,000 ethnicities resident within Africa. This is not the place to describe the history of Pan-Africanism found in Appiah’s tightly argued book. Suffice it to say that Appiah rejects the claim that Africans are part of a singular distinctive “race.” Africans do not have a single-shared language, religion, or culture, but they do have shared issues of 19th and 20th century development and politics (e.g. colonialism, “artificial boundaries,” nationalist and independence movements), current projects, governance, and development issues, and can learn from the experience of one another and from the rest of the nation-states of the world. Here, Wentling and Appiah agree: the former relying upon decades of “first-hand experience,” the latter relying upon his own personal and family history in Africa as well as historical, scholarly research. “Growing pains remain,” in Wentling’s opinion.

Wentling is concise in answering the simple question: What are the interests of the US in Africa? The many peoples of the US share Africa as our original home; we are descendents, over thousands of generations, of the species Homo sapiens and Homo sapiens sapiens. Today, 12 percent of Americans can trace their ancestry to the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, the consequences of which we continue to discover. We have, Wentling continues, humanitarian interests in Africa. We have strategic interests in gaining access to Africa’s natural resources (e.g. oil, cobalt, chromium, platinum, uranium, diamonds/gold) and monitoring the tactical activities of China, Europe, and others who are also negotiating to control Africa’s resources to enhance their own economies. And, Wentling reminds us, we have an interest in combating terrorist organizations in Africa. In “Africa: A Mixed Bag of Good and Bad” and “What Does the Future Hold for Africa?” you’ll find some surprises, perhaps: for example, there is an effort to create a single continental market for the 54 countries; he names the countries which have never experienced a significant conflict; and states that Africa has 60 percent of the world’s potentially agriculturally productive land.

But, Africa remains the poorest continent on the planet, he says, and features both poverty and extreme poverty. The “average African” lives on 70 cents per day income, Wentling writes. Still, he believes that with better leadership free of “corruption,” Africa can overcome its barriers to greater overall success. What role can various types of “aid”–his specialty–play in assisting Africa to meet its developmental challenges? In Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is A Better Way for Africa (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009), Zambian economist Dambisa Moyo Ph.D. contends that $1 trillion in development-related aid has not improved the lives of Africans. Quite the opposite, she says: it has made Africa dependent upon it. In his Forward to the book, Niall Ferguson writes that Moyo’s “crucial insight is that the receipt of concessional (non-emergency) loans and grants has much the same effect in Africa as the possession of a valuable natural resource: it’s a kind of curse because it encourages corruption and conflict, while at the same time discouraging free enterprise.” Reading Africa Memoir, look for Mark Wentling’s perspective on this controversial matter because he has directed or consulted on dozens of aid projects across the continent. See if he distinguishes between US government foreign aid (including PEPFAR) to Africa and the many Non-Government Organization (NGO) and International NGO (INGO) assistance programs for educational and medical purposes. Anyone who has visited or lived in Africa for even a short time will understand, in this reviewer’s opinion, that government assistance or that of NGOs does not discourage African entrepreneurialism. Africans do, however, complain that cheap Chinese products when allowed unlimited access to their markets is unfair competition. But, African countries are alive with bustling markets large and small, and entrepreneurs, women and men, who now make extensive use of cell phones in planning the harvesting and transportation of agricultural products for example. Rural residents, in my experience, also look for NGO financial assistance to transport themselves in groups to the seat of government offices to demand a greater share of government resources for technical assistance, schools, and health services.

Below are a few examples of personal observations Mark Wentling offers in Volume I of Africa Memoir.

Botswana

In Botswana, Wentling learned that the country, “with a high adult HIV/AIDS prevalence rate” near 20%, “developed a model program to tackle the HIV/AIDS pandemic.” The county also has a high rate of alcohol consumption among males, a “huge problem … in many parts of Africa.” It may be Botswana’s primary social problem. But, “Botswana’s development profile is one of the best in Africa and it is among a handful of higher income countries in Africa.” It has a strong democracy, “highly educated and enlightened leaders, free press, independent judiciary,” and “well-functioning institutions that would be the envy of any country.” It is a “shining example” but not one followed by many African countries. It’s leadership has followed policies “in the best interests of the country and its people” since independence from Britain in 1966. Also, it has a low population of two million people and it has a large diamond-mining industry which has produced “a level of prosperity not known elsewhere in Africa. Good leadership, high education levels, full employment and impressive per capita wealth make it easier to implant democracy and make it work to the advantage of Botswanans.” The fertility rate is the lowest on the “mainland continent. Many of its population statistics are akin to levels that prevail in the most advanced non-African countries.” It’s very urbanized and there is no violent conflict producing instability. Thus it demonstrates predictable circumstances which benefits the government, populace, and investors. It also benefits, overall, from being a neighbor to South Africa’s big economy and from being integrated into the Southern African Region. On the other hand, the capital, Gaborone (Gabs) is described by visitors as “boring.” But that’s better than being a city of chaos or one “living on the edge of survival.”

Burkina Faso

“This is a country that is dear to my heart and has left me with some indelible memories.” These include “one historical day things reached the boiling point and Africa experienced a rare successful popular insurrection. The final straw for the people was the insistence of its long-serving president [27 years] to amend the constitution so he could run for another term. For the people, this was too much and enough was enough.” That was in October 2014. Wentling was then married to Almaz (born in Ethiopia), a woman with whom he had children. The family left for the United States in 2015, though Wentling has returned alone to Africa to work on development projects since then.

Burundi

“I have not set foot in Burundi for over twenty-five years, but for all this time I cannot get out of my head the words said to me by a local acquaintance. He said, ‘We have to kill them before they kill us.’

“My reaction was, Who are they?

“He looked at me with some incredulity and said, ‘I’m Hutu and they are Tutsi.’

“I quickly inquired, How do you know who is who? All of you look the same to me.

‘We know. Don’t worry about that. Sometimes we don’t know immediately, but after we talk a while, we know,’ he responded with remarkable ease.”

Cabo Verde (Cape Verde)

Mark Wentling visited only the Amilcar Cabral International Airport in the country. He made no pretense of going beyond the airport in 1985 while awaiting a connecting flight to Dakar, Senegal. Technical difficulties had required a forced landing. Still, he made the most of it, noting that the former Portuguese colony “has all the development statistics of a more advanced country. … One thing that sets Cabo Verde [population 500,000] apart is that more of its people and their descendents reside outside of Cabo Verde than inside this country, which is about the size of … Rhode Island.” Many “Cabo Verdeans and their offspring live in the State of Massachusetts.” Wentling was impressed with, “The smooth functioning of Cabo Verde’s airport restroom …”. And, that’s enough said about Cabo Verde.

Cameroon

“I almost drowned in Cameroon. This is not something I want to write about.” And yet, he does. The pirogue (a hollow tree trunk) in which he was being transported began to take on water, “a gushing fountain.” “I also feared being eaten by a crocodile or crunched by an errant hippo.” He survived. Young people represent the majority of the population, but they lack political resources. “Democracy is a sham in Cameroon and other African countries where it has been turned on its head to keep power in the hands of the aging few. It has been said that democracy in Africa is a mile wide and an inch deep. In Cameroon, democracy has even less depth.” President Paul Biya was in power for 38 years.

Central African Republic

“It is not a simple task to write about a country that is not really a country.” Europeans drew the boundaries of CAR in 1960 and determined its name. The French were “irresponsible” in granting independence “prematurely.” Perhaps the United Nations should have administered the state until peace and stability was achieved; regardless, the UN or a consortium of “developed countries” should be appointed to do so now. Wentling spent three months in Bangui, the capital, as Acting Country Director of the Peace Corps. One Bangui Peace Corps Volunteer tried to deter thieves from stealing repeatedly from his apartment building by hooking up an electric current to run through the iron bars covering the windows. “The thief came again and as soon as he touched the iron bars he was electrocuted and died.” The thief’s family filed a lawsuit of wrongful death against the PCV. The result: see page 57. In 1979, because of the “zany [President] Jean-Bedel Bokassa,” who wanted to have himself crowned, as Napoleon did, as an Emperor, the French sent a military contingent to dethrone and replace him. The country is still badly managed and dangerous. In October 2018, the U.S. Department of State issued a travel advisory which began, “Do not travel to the Central African Republic …”

Chad

“Forty years ago, I did not know much about Africa. I did not know then that many of my schemes were hair-brained and wacky in nature …”. One of these “schemes” was traveling overland “around the northern and eastern shores of Lake Chad” as he did in 1978 when he was living in Nguigmi, Niger, “on the northwest shore of Lake Chad and we had a couple days of slack so I jokingly said in French to my driver, Ibrahima, Let’s go to Ft. Lamy,” renamed N’Djamena. There were no roads to N’Djamena on the north side of the lake but smugglers sometimes used the route, so why not do as they do? Naturally, they became mired in deep sand multiple times. Six-foot track runners helped them move six feet at a time in the boiling sun. No people were visible to ask for help. “It was really stupid and life-threatening…”. After nearly an entire day, they had gone 100 miles, with no air-conditioning and the necessity of keeping the car windows closed to prevent being “covered with road dust.” At sundown they arrived, found a cheap hotel, drank bottled water, ordered dinner, and showered outdoors using calabash gourds to splash water on themselves. Dinner was grilled Guinea fowl and “limp potato slices”: “a very tasty meal…”. They slept on straw mats “in a hot room full of mosquitos with large rats running about above us in the rafter boards. The mats were covered with layers of cloth to make them softer. The pillows were stuffed with straw and hard as a rock. The mosquitos kept me awake by buzzing in my ears …”. Early the next morning, following a breakfast of green tea and instant Nescafé, they returned to Niger, fearful of being detained as “smugglers”: “It was not the kind of place that encouraged trusting anyone; all you wanted to do was to leave before anyone knew you had been there.” Once back, Wentling and Ibrahima “swore ourselves to secrecy,” vowing never to reveal their trip. But, now, with Africa Memoir, “The secret is out …”

There follows a long description of Chad’s ethnic conflicts, a failed attempt to use oil reserves to promote health, education, and other development projects. Still, Chad remains impoverished, “in the lowest ranks of the UN’s human development index.” “(G)ood and honest national leadership” is missing.

Ethiopia

“I have been to this country several times and I have learned much about it from my wife [Almaz], who was born and raised in Ethiopia. This abundance of knowledge about Ethiopia does not, however, make writing this chapter any easier. I live with Ethiopia every day, but it has taken me the longest time to even attempt a draft of this challenging chapter.”

Ethiopia is a “unique country in Africa and in the world. Ethiopia and its long history really defy any acceptable description in a short chapter.” Wentling first went to Ethiopia in 1983, after 13 years in Africa, to develop a plan to find and distribute “thousands of tons of U.S. food aid to tens of thousands of Ethiopians who were on the verge of starvation, following a serious period of drought.”

Much later in the chapter, Wentling writes, of the positive impact of “diaspora” Ethiopians living abroad who provide remittances (money) but more than that: “Many members of the ‘diaspora’ return home and invest in their homeland and start businesses they learned to operate while abroad.” This is true of not only Ethiopia but many other countries as well, in the experience of this reviewer. In part, the motive is financial, but also those who return say that technology allows them to do their jobs as easily in, for example, Nigeria as in New York; and they can raise their children as “Africans.”

“During this last visit to Addis,” Wentling remembers, “I was asked by a friend, John Coyne, who had taught high school in Addis in the 1960s as a PCV to take photos of his old school.” The school was found but “had grown substantially over the years and had evolved into a college.” There were now “tall skyscrapers next to the school, casting long shadows over what was once a small education institution. I was told that these tall buildings were built by the Chinese.” In fact, the Chinese had many projects in Ethiopia and “had lent huge sums of money to the government of Ethiopia.” One project was “a critical rail line to Djibouti Port, giving Ethiopia a much-needed outlet to the seacoast. Ethiopia is the largest landlocked country in Africa.” The Chinese also built a light-rail line in Addis, and provided Ethiopian students with scholarships to study in China, which will have an “impact on Africa’s future.”

With a population that has grown from 38 million people in 1983 to 108 million people in 2018, Ethiopia’s numbers now rank second only to Nigeria in Sub-Saharan Africa. And, its population has a median age of 19, versus 38 in the U.S. How, Wentling asks, will Ethiopia (and Africa generally) “feed, clothe, shelter, educate, care for and employ so many people”? “[C]urrent projects point to a situation where the world’s poverty will be mainly concentrated in Africa in the future.”

Ghana

Mark Wentling first visited Ghana in 1970 because he was assigned to work as a PCV in neighboring Togo, 10 miles from their shared border. “I worked in several rural communities that straddled the artificial border with Ghana. In fact, one of the villages was legally in Ghana. Sometimes, I was on the ‘Ghana-side’ without knowing it.” Ghana was then viewed “as a kind of superpower which was a source of wealth and well-being.” It was a model for countries whose goal was economic independence. It would help West Africa to achieve that status.

It seemed in 1970 that within a few years, West Africans “would not need any more external assistance”: they would be “developed nations. As naive as I was at the time, I joined them in their optimistic outlook.”

“Currently, in 2020, I am still waiting for the best performing low-income countries in Africa to be weaned off external assistance. Many of the lowest-ranked African countries have been ranked near the bottom of this list since the creation of this index in 1990. Some of these countries have been held back by protracted conflicts while others have not known any widespread violent conflict but have been devastated by national mismanagement and corrupt leadership.” Ghana became “a shameful example” of “misguided leadership.” For example, “The building of the Volta Dam and many other grandiose projects helped drain the Ghanaian treasury.” National political leaders “increasingly alienated Ghana’s strong traditional chieftaincy system and members of the educated elites.” President Kwamena Nkrumah “was removed by a military coup in 1966 … .” Other coups followed; the economy and currency collapsed. Educated abroad, Nkrumah introduced “radical ideas and policies enacted in an increasing authoritarian manner….In many ways imported noble ideas did not work well in practice in Ghana.”

Wentling refers readers to the book by French agronomist Rene Dumont, False Start in Africa (1962) and his argument “that newly independent Africa started on the wrong track because its first leaders did not come from the class of Africans who were best suited to lead their new countries in the initial years of independence.” Once the “wrong track” was chosen, it was “almost impossible to shift to a better path which leads to higher levels of development and prosperity for its people.” Ghana is such an example. The economy was in shambles in 1972.

Ghana suffered another coup in 1979, which resulted in the murder of three former military presidents. Extreme measures were taken to “create a new destiny for their country.” Flight Lieutenant Jerry Rawlings and the government received the “external financial assistance” needed and a new government was elected.” Wentling was most impressed by the firm establishment of multiparty democracy in Ghana and the high qualities of its well-educated presidential candidates. Ghana has now had a series of presidential elections that serve as a model for other African countries.” Ghana still faces “many problems,” Wentling says, but it “has come a long way in the last forty years.”

In an earlier novel, Africa’s Embrace (A Peace Corps Writers Book, 2013), Mark Wentling’s protagonist, “David, who was re-baptized ‘Bobovovi’ in Africa,” is, like Wentling himself, a boy “born and raised on a farm on the plains of Kansas.” After working for decades in Africa, Bobovovi eventually becomes—literally—a part of the landscape, as witnessed by the plaque which reads: “Here Dwells Forever the White Baobab / His Destiny Fulfilled / Born in Kansas for Africa.” “This,” the novel concludes, “was indeed Africa’s final embrace.”

Although not a math major or one who regularly consults the Las Vegas Line before a boxing match or football game, I will give you 2-1 odds that Mark Wentling will never be transformed into a White Baobab. But, he certainly did transform himself over five decades from a child of Wichita, Eldorado, and Udall, Kansas, into an experienced development specialist working in Honduras (1967-69) as a Peace Corps Volunteer and then in Africa, beginning in 1970 in Togo for the Peace Corps and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

If there is one disappointing aspect of Africa Memoir, it is that Mark Wentling does not discuss at greater length the various project’s he directed or to which he consulted for USAID and other organizations. Even that criticism is unfair in that this review ends with Liberia and therefore does not include his management of “one of the most complex integrated rural development projects in West Africa, the Niamey Department Project” for which he received a Superior Honor Award from USAID “and an unprecedented commendation from the Government of Niger,” according to the “Biographical Sketch” he made available to this reviewer. He also managed regional projects which included agricultural research, rural credit, and private sector development. There were other posts directing the Southern Africa Drought Emergency and African Disaster Assistance Task Force, including the Somalia working group and as USAID director in Somalia, later as USAID director in Tanzania. He worked for CARE in Niger and Mozambique, and for World Vision covering all its African projects. More recently, Wentling worked for USAID/West Africa in Accra, Ghana (2016-17) as a Senior Agriculture Advisor and had the same position later in Mali.

Mark Wentling’s formal education includes completing his Bachelor of Arts in economics, political science, and anthropology in 1970 at Wichita State University, where he also received the Alumni Association Achievement Award in 2014; a Master of Science with Honors degree in tropical agriculture, livestock, and agricultural economics in 1983 from Cornell University; and a Master of Arts degree from the United States National War College in international strategic studies in 1992, where he was awarded the annual writing prize for his paper, “Redesigning U.S. Assistance to Africa in the Post-Cold War Era.”

The President Dwight David Eisenhower Memorial in Washington D.C. includes, among others, a statue of a boy looking towards other statues commemorating the various roles and accomplishments of Eisenhower during his life. Eisenhower was a child of Abilene, Kansas. While Mark Gregory Wentling may never morph into a White Baobab in Africa or have a bronze statue erected in his honor in the nation’s capital, the following accolade is plausible:

Two former classmates meet again for the first time since commencement at their Old Guard 50th Anniversary. They greet each other warmly and shake hands.

Enrique: “You look great, LaShandra! What have you done since graduation?”

LaShandra: “Well, I joined the Peace Corps, and then, for 50 years, I did ‘A Wentling’ in Central America and Africa. And you?”

•

Robert E. Hamilton (Ethiopia 1965-67) received a Ph.D. In African history and anthropology from Northwestern University (1978). He was a university lecturer in African as well as Asian Pacific Rim history. In the corporate world, he worked for coal mining, trucking, and communication firms and was a stock broker for many years as well as a strategic planner for a large law firm. He consulted to business, medical, and educational projects as their African field director and was director of a nonprofit corporation with projects in Africa and India.

He has published two Kindle books of fiction at Amazon (Dr. Dark; and Short and Shorter: Short Stories and Poetry). His latest book, Highway 1, is available electronically at no charge by contacting him at: Robu43@gmail.com. He is currently working on the next book in his series The Hillsdale Narratives.

No comments yet.

Add your comment