“Return” by Kathleen Coskran (Ethiopia)

Notes from the Editor: Kathleen Johnson Coskran (Ethiopia 1965-67) taught in Addis Ababa her first year, then transferred to Dilla, a small town in the far south of the Empire. She wrote “So This Is Paris” about Dilla, an essay Marian Beil and I published in our newsletter, RPCV Writers & Readers in 1994. For me that essay is one of the finest written about the Peace Corps experience. I republished it in a collection I edited titled, Peace Corps: The Great Adventure.

In 2007 Peace Corps Writers.com publish “Second Time Around” that subsequently received the 2008 Peace Corps Writers Moritz Thomsen Peace Corps Experience Award.

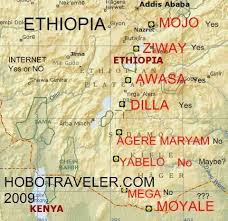

Kathy has continued to write and continues to win awards. This is an essay she wrote about when she and her husband Chuck returned to Ethiopia and traveled for ten hours by bus through the Rift Valley to see Dilla one last time. Here is her short introduction to the circumstances that surrounded her trip back to Ethiopia with Chuck in 1997. And here is the name of her other story of when Chuck and she visited the president of Ethiopia Negasso Gidada. We published it on our site on October 8, 2020. It is entitled, “Teacher”

Kathy writes…..

Chuck and I traveled to Ethiopia in 1997 for two reasons, to visit Dr. Negasso Gidada, who had been Chuck’s student at Bede Mariam Lab School in Addis Ababa, and also to visit our foster son Ahmed’s family in Harar. Dr. Negasso, then president of Ethiopia, had invited us to visit if we were ever in Ethiopia, and Ahmed was returning for the first time after fleeing nearly 20 years earlier during the most violent days of the Derg, the military junta that ruled Ethiopia from 1974 to 1987, (but stayed in power until 1991.)

When I visited Ahmed’s family in 1989, I met several Ethiopians who also fled earlier, had become American citizens, and were able to return. When I was home again, I encouraged Ahmed to become an American citizen, which he immediately did. However, his application for an Ethiopian visa was denied because he didn’t have an Ethiopian passport to prove he had left the country legally. (He hadn’t. He was 12 years old when he and his brother Abdul Nasser made it to Djibouti — hiding during the day, walking at night — and were eventually placed in refugee camps in Egypt.)

Five years later I answered a call from the Ethiopian Embassy in Washington, D.C. “Tell Ahmed he can go home,” the caller said. The laws had changed, Ahmed got his visa, and would arrive in Harar a week or so before we did. We would get there several days after Ahmed to celebrate his reunion with his family. That was the plan.

It wasn’t possible to visit Dilla when I was in Ethiopia in 1989. At that time a foreign visitor could only leave the capital city if traveling to see a relative and had a permit to do so. I said I was going to Harar to visit my son’s father, paid the US$15 fee, and they let me go. (I tell the story of that visit in “Proxy,” in Tanzania on Tuesday, New Rivers Press.)

By 1997 it was possible for foreigners to travel throughout the country, so, in addition to visiting President Negasso, we planned to arrive in Harar a few days after Ahmed, to celebrate his reunification with his family, and then to Dilla. But, unknown to us, Ahmed had some complication with his travel plans, and we arrived in Harar a day before he did, so when he stepped through the gate of his family’s compound for the first time in 18 years, there were both sets of parents, his father Mohammed and his mother and Chuck and me!

After three days in Harar, we went back to Addis Ababa and took the bus to Dilla, which I describe in “Return.” It was an emotional two weeks.

•

Return

by Kathleen Coskran (Ethiopia 1965-67)

I KNEW MY STUDENTS wouldn’t be waiting for me in Dilla; they were middle-aged now, or dead. It was the educated who were assassinated during the Red Terror after I left Ethiopia, after the coup, after Haile Selassie was deposed, and the “cleansing” of the new Marxist regime began. We were told that every family lost somebody, but maybe my students were too young or too far from Addis Ababa to be noticed. I knew I wouldn’t find them, but after thirty years, I had to go to Dilla to see the school and my house and to eat at Amare’s bar and to walk to Andida.

My husband, Chuck, and I took the bus, still a ten-hour ride from Addis. I waited for the panoramic view you get of the town as the bus rolls down the switchbacks from the ridge at Kabado to Dilla, low at 5500 feet, waited to see the four dirt roads lined with white washed mud houses, the bus park on First Street, my house and the school on Fourth Street and the wild green mountains beyond. The first time I got off a bus in Dilla, I didn’t know where to go, so I asked a boy at the bus park where the Peace Corps lived and he took me to what would be my house. In those days every boy was eager to walk with you or help you and knew just where to go. But I knew Dilla now— we wouldn’t need a guide.

Suddenly we were there, but without the dramatic descent or view of the town I’d waited for. The main road had shifted, the four streets were many streets, the population had tripled and the town was now dominated by an enormous mosque at one end and a massive Coptic church at the other. Nothing was familiar. We walked every street, but I couldn’t find the post office or Amare’s bar where I had eaten lunch every day or even the house I’d lived in. We couldn’t find Atse Dawit School where I’d taught sixth grade English and seventh and eighth grade math. So I did need a guide after all. We asked a boy, two boys, to help us.

“You looking for the high school?”

“There’s a high school? No, not the high school. Atse Dawit School.”

“Our school, Madam.” They were brothers, Mulukan, 13, and Kibro, 10.

They led us to the long grassy path I’d walked up every day to the mud and stone building with the tin roof that was Atse Dawit School. The soccer field was still on the right, where I’d stood with my homeroom, 7A, every morning to sing “Ethiopia Hoy,” the outhouses still swarmed with flies, the old building still badly needed whitewashing.

It was July, the doors were locked, but Mulukan and Kibro took us to every room, made sure we looked through every window. I pressed my hands and face against the window into 7A. It looked exactly the same: rough wooden desks meant to seat two, more often holding four, the scarred chalkboard, stained, crumbling walls, no lights, no pictures on the walls, no shelves for books, no books. That beautiful, ugly, barren room was proof that I didn’t dream the whole thing, that I had once stood in that dim classroom, writing on the scratchy board, solving for x with seventy-five wide-eyed students as rain drummed on the tin roof.

For a moment I was 23 again and the two radiant boys, Mulukan in his jeans and faded striped shirt and skinny Kibro in windowpane plaid shorts that hung to his knees were my favorite students reincarnated, eager to help, hungry to learn, promising to show us everything. What else did we want to see?

Andida. I wanted to go to Andida. Walking to Andida had been a destination, something to do in a place where there was nothing to do, a village smaller, poorer, more remote than Dilla, accessible only by foot, an hour’s walk up the mountain. The rich rode horses; the poor and Peace Corps Volunteers walked.

It was market day in Dilla, so we passed a steady stream of people coming down the mountain as we climbed up, most toting bags of onions or giant inset leaves, that draught-resistant miracle plant that shades the tender coffee bush and provides the starch that is the staple of the local diet. Everybody stared at us, the women laughing behind their hands and the men offering a hand and calling us ferenji. The ruts were deeper than I remembered, there were more people on the path and more huts along the way. No rich men on horses but a wild man on a rusty scooter bumped down the mountain, dodging ruts wider and deeper than the tires of his old machine.

It was market day in Dilla, so we passed a steady stream of people coming down the mountain as we climbed up, most toting bags of onions or giant inset leaves, that draught-resistant miracle plant that shades the tender coffee bush and provides the starch that is the staple of the local diet. Everybody stared at us, the women laughing behind their hands and the men offering a hand and calling us ferenji. The ruts were deeper than I remembered, there were more people on the path and more huts along the way. No rich men on horses but a wild man on a rusty scooter bumped down the mountain, dodging ruts wider and deeper than the tires of his old machine.

As we crested the rise and neared the village, Mulukan asked if we wanted to see the church. I’d never seen a church at Andida. Maybe it was a grand, new structure like the impressive mosque in Dilla. Maybe there was an old one with the traditional courtyard and octagonal church building, the outer ring for women, the next for men and the inner circle protecting the ark of the covenant. Maybe the church would be resplendent with ancient paintings of saints or angels. Thirty years earlier on a walk to Andida we had discovered ancient stellae in a patch of corn outside a hut . . . and felt we had uncovered Tut’s tomb. Maybe a revelation awaited us. Yes, we wanted to see the church.

They led us off the road, through a eucalyptus forest, and then down a wide path lined by twelve-foot high inset plants. Clutches of old men draped in white, leaning on their sticks, flanked the path. They nodded as we passed, as if they’d been waiting for us. We arrived at a squat mud building with a corrugated tin roof in the center of a broad clearing at the crest of the mountain. Where is the church? Here, Mulukan said. He glowed as he pointed to the sagging shack. The door was locked. Wait, he said.

Chuck and I stood at the edge of the clearing and stared down the mountain we had just climbed. The vegetation was deeply hued and abundant, giant inset against the pale eucalyptus, the inset so green and lush that it left an impression of plenty wherever it grew. Mulukan soon returned with a priest and a key to the church. We stood respectfully outside the door and peered in. Mulukan urged us to enter, but I couldn’t. Women are never allowed inside the central area of a church and this church only had the center, one room, with a printed picture of St. George on the far wall, a sagging table, a candle, one chair, a bit of cloth draped over the one window, a fly whisk hanging on a nail. It looked like an abandoned storeroom. There was nothing about this shack that said “church” except the pride in the faces of the two boys who knew we’d want to see it and the reverence of the old priest who opened the door. Beautiful, we said. Thank you.

We went to the Andida market, but nobody was there because the market was in Dilla that day. Weekly use had so sculpted the earth of the Andida market that you could imagine the people there, selling, buying, arguing. Years of trading had carved a maze of trails that looked like some kind of natural formation of gullies and plateaus. The flat areas where women sat on the ground before cloths piled with spices, flours, or beans were smooth and elevated above deep trenches carved by bare feet. It is empty, Kibro said. He was disappointed for us. No, I said. It is okay. That spectral market showed me that thirty years had indeed passed, but during those years of deep trouble in that beloved country, people had grown inset, ground it, sold it, bought it, walked to market, walked back, carving their footprints deeper in the earth. It was good.

As they led the way back down the mountain, Kibro slipped his hand into Chuck’s as if it were the most natural thing in the world, boy and man, hand in hand, to show us we were still connected, to show us why we’d come.

The Coskran Family in 1985 — (L to R) Kathleen, daughter Anna, son Alex, Chuck, son John, son Ahmed

•

Kathleen is currently working on a book about the lack of justice in the multiple criminal justice systems in the United States, based on her 25-year friendship with James Colvin, who has been incarcerated for nearly 50 years.

Thank you an excellent descriptive memory. Bill Donohoe (Ethiopia-62-64).

Lovely descriptions, I could see the empty market and most of all the two boys, so eager to help.

Dear Kathy,

What a beautifully written and compelling story, or stories, really. You take your readers along with you, to the classroom, the church, the empty market. I want to know more about your experience there, more about Ahmed’s escape,.

Thank you so much for sharing this. Please share more,

Julie

Each time I read one of your beautiful pieces on this country you so clearly love, I want to be there, only with access to a vehicle and a hot shower at days end.

Kathy, thank you so much for sharing this with us now — and for your evocative writing!

Kathleen, Thank you for taking me with you and Chuck on your 1997 trip to Ethiopia, with your words – visually, geographically,

culturally, and emotionally.

Brava, Kathleen! You capture the vivid memories stored in the minds of all who spent time in Ethiopia in the old days. I’m glad you had Chuck with you to share in yet another adventure in that fabled land.