2020 Peace Corps Writers’ Rowland Sherman Award for Best Book of Photography — ALTAMONT 1969 by Bill Owens (Jamaica)

Rowland Scherman

Rowland Scherman was the first photographer for the Peace Corps in 1961, documenting the work of Volunteers all over the world. His photos helped define the image of the agency we know today. He became a freelance photographer in 1963. His photographs have appeared in Life, Look, National Geographic, Time, Paris Match, and Playboy among many others.

Altamont 1969

Altamont 1969

Bill Owens (Jamaica 1964–66), photographer

Damiani Publisher

May 2019

$26.99 (Hardcover)

On April 15th of 2019, The New York Times published he following article about Bill and photographing at Altamont: “50 Years After Altamont: The End of the 1960s.”

50 Years After Altamont: The End of the 1960s

A reluctant rock concert attendee, Bill Owens nevertheless photographed the disastrous 1969 music festival Altamont and the close of an era.

A half-century ago, 1969 capped a radical, idealistic decade that saw the rise of the hippie generation and the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Woodstock, perhaps the most famous concert ever, happened that summer, with free love and drugs serving as backdrops to sets by Jimi Hendrix, Santana, Richie Havens and others.

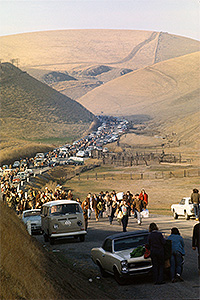

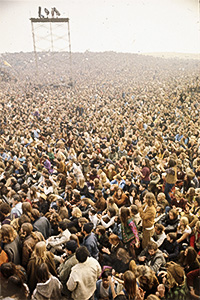

But another large, raucous rock festival that year — Altamont—became notorious for very different reasons. That December, the Rolling Stones and the Grateful Dead organized an impromptu concert at Altamont Speedway, in the golden hills of Northern California’s East Bay, that drew an estimated 300,000 people. Four people died, including a man who was killed by members of the Hells Angels who had been hired to provide “security” for the event.

So much for peace and love.

The [Altamont] concert was featured in the documentary film “Gimme Shelter,” and a few photojournalists captured the experience. Among them was Bill Owens, who would soon rise to photographic fame for his seminal early 1970s project Suburbia, which cheekily documented the rise of the suburbs in California.

In December 1969, he was working as a photographer for The Independent, a newspaper in nearby Livermore, Calif., when his friend Beth Bagby and her boyfriend, Robert, who worked for The Associated Press, called to see if he wanted to shoot the concert. His editors gave him the day off as long as he let them publish a photo of the gathering.

Altamont 1969 — Bill Owens

The concert was going to be on a Saturday morning,” he recalled. “For some reason I had a motorcycle, probably because it was $85. So I drove my motorcycle out, and I went on the back roads. People were abandoning their cars, so pretty soon I had to ditch the motorcycle, because there was a barbed-wire fence there, and I couldn’t take it up this hill.

Altamont 1969 — Bill Owens

He got there early with two cameras, three lenses, film and a jar of water. He climbed up the sound tower to get a bird’s-eye view, which gave him a sense of the concert’s sprawling scale.

Several hours later, a Hells Angels biker climbed the tower and threatened to bash his head with a pipe wrench and toss him off the tower if he didn’t come down. Since he’d used up all his film by then, Mr. Owens happily obliged and slowly made his way back to his motorcycle to go home. As he later wrote: “People fighting on sound towers only happens in the movies, and the good guy wins. Reality is different.”

Mr. Owens didn’t even like rock concerts as he was a few years older than the hippies surrounding him, and he wasn’t interested in “dope.” He just wanted to go home to his family, put on the TV and watch Walter Cronkite.

Ms. Bagby stayed into the night, and photographed a Hells Angels member stabbing an African-American man, Meredith Hunter, near the stage as the Stones played. Mr. Owens didn’t know anything had gone horribly wrong until the following day.

Altamont 1969 — Bill Owens

In addition to pictures of Mick Jagger making his way through the crowd, and Jefferson Airplane and Santana on stage, Mr. Owens managed to capture images of the Hells Angels beating people with pool cues, and feared his family might be at risk.

Not taking any chances, he published his images under a pseudonym.

When the images appeared in Rolling Stone and Esquire all over the world, I had two or three different aliases on different images,” he said. “I would not publish my name, because my name is in the phone book, and I don’t want anybody associated with the Hells Angels to come looking for me and shoot me thinking I was the one who shot the photographs of the guy being murdered.

“I’ve got a wife and a kid, and a second kid coming along. You want to be watching TV in the night time. You don’t want to be sitting there with a gun trying to protect yourself. I don’t want anything to do with that culture.

After the images were published, Mr. Owens and Ms. Bagby lent their negatives to a young couple who planned to include them in a book, but their house was burglarized and the thieves took all the negatives. Mr. Owens blames the Hells Angels, who he suspects weren’t interested in evidence remaining at large.

The few pictures that survived have been collected in a new photo book, Altamont 1969, that was recently published in Italy by Damiani Books. It’s a fascinating collection of photographs, in addition to being an important document of a turbulent chapter in American cultural history.

It’s also a surprising series to those who know Mr. Owens for his funny, warmhearted projects from the 1970s, and perhaps also to those who know him only as one of the founders of the craft beer brewing and craft distilling movements in the United States. Mr. Owens also served in the Peace Corps and took a hitchhiking trip around the world.

The Altamont project, which relied so heavily on being present at a particular moment, seems an outlier compared to the rest of his work. In 1978, he published a manual about how to become a documentary photographer, in which he wrote:

Each year prizes are given to photographers who were at the right disaster at the right time: a shot of someone falling to his death, or better yet, a photograph of someone holding a gun on a hostage, and being blasted at by the cops. My photographs of violence are not a source of personal pride.

But at 80, having lived a rich and varied life, Bill Owens is thrilled the book will be a part of the cultural conversation.

And he’s glad it’s happening now.

“I know now, at age 80, God can take you,” he said. “Within three months, I can go. A lot of people have gone already. I read the obits. When you’re ready, something can be cooking inside of you, and you’re gone, and I’ve got this legacy to take care of.”

•

Of his start in photography, Bill has said in an interview here on Peace Corps Worldwide:

I started taking pictures in Jamaica. A Peace Corps photographer came to our village and took pictures of us and the other Volunteers and as soon as I saw what he was doing, I said, “Oh my god, I want to be a photographer.” So I bought a Leica camera and started taking pictures. I bought it for $10 because it had a pinhole in the curtain, the little fabric curtain that opens to take a photograph. I took shoe polish and plugged up the pinhole and so that camera worked fine. I just figured it out. You got plenty of time when you are in the Peace Corps.

•

No comments yet.

Add your comment