2020 Peace Corps Writers’ Maria Thomas Award for the Best Book of Fiction — WITH KENNEDY IN THE LAND OF THE DEAD by Will Siegel (Ethiopia)

Roberta Worrick

THE MARIA THOMAS FICTION AWARD, first presented in 1990, is named after the novelist Roberta Worrick (Ethiopia 1971–73) whose pen name was Maria Thomas. Roberta lost her life in August 1989, while working in Ethiopia for a relief agency. She went down in the plane crash that also killed her husband, Thomas Worrick (Ethiopia 1971–73), and Congressman Mickey Leland of Texas.

Mrs. Worrick’s novel, Antonia Saw the Oryx First, published by SoHo Press . . . in 1987, drew critical praise for its depiction of the tensions between colonial whites and Africans on a continent buffeted by changes. After the success of the novel, Soho Press issued Come to Africa and Save Your Marriage, Mrs. Worrick’s collection of short stories in which she told of the difficulties of various people — Peace Corps Volunteers, foreign academics, Indians, American blacks and white hunters left behind by colonial empires — in finding their way in black Africa. — NY Times 8/14/89

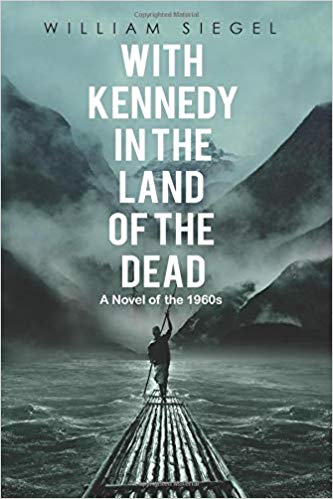

With Kennedy in the Land of the Dead

With Kennedy in the Land of the Dead

By William Siegel (Ethiopia 1962–64)

Peace Corps Writers

355 pages

January 26, 2019; $20.00 (paperback), $9.99 (Kindle)

Reviewed by Sue Hoyt Aiken (Ethiopia 1962—64)

The author, like myself, served in those very early days of the Peace Corps. We had elected to serve as high school teachers throughout Ethiopia at Emperor Haile Selassie’s invitation beginning in September, 1962. Around 300 of us landed in Addis Ababa eager to serve and demonstrate we could carry out President Kennedy’s call: Ask not what the country can do for you but what you can do for the country! Who knew of the tragedies that would unfold starting in 1963 with John F. Kennedy’s assassination up to and including the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King? Camelot was unmistakably over.

The author has the narrator, Gilbert Stone or Gil, begin his story as he arrives in Ethiopia full of great dreams of all that lay before him as a Peace Corps Volunteer teaching in a rural village. Like most of us he was fresh out of college having never taught on his own a single day of his life. We were a mystery to our students as Gil experienced. Gil taught blind boys thus stretching his imagination to the fullest. And then comes the news! He begins his unwinding, ungluing, unhinging when he learns of Kennedy’s assassination from his students who believe it is a revolution. He rushes to Addis Ababa to confirm, but the reality of horror and disbelief could not be comprehended in any logical, sane manner by Gil. Kennedy was his hero, his warrior for making the world a better place and essential to Gil’s dreams.

Arriving home a few months later in the summer of 1964 Gil finds no one with whom he can relate the significance of his shattered dream. Except for Kennedy who he can see standing nearby watching. Of all places to move to San Francisco was on the cutting edge of rebellion, breaking away from the norm and the Vietnam War. Berkeley was the seat and full center of resistance on almost everything and especially fighting a war no one wanted. Like Gil, I attended school for a year after returning. I was at UC Berkeley while Gil was at San Francisco State and living in the Tenderloin. His apartment and housemates became a commune open to all including a stash for drugs. Central to this story is the influence of both drugs and increasing disillusionment followed by hysterical, wild antics as Gil’s hopes focused on stopping the war.

The author’s incredibly vivid drug-induced head trips are at once painful, terrifying and remarkable for the descriptive lyrical scenes like,

Gil is witness to a blood-swept eternity that tears the lenses from his eyes. And still, it does not stop victims’ cough and gag with disbelief, blood splashes from mouths, and body wounds as agony twists faces. Shrieks curdle the air. Body parts litter the ground. Blood drenches the sun and smears trees. Suffering and disbelief gleam on the eyeballs of the lifeless. (p.212)

His dreams climax with a vision of Death itself and a conversation with Kennedy in the Oval Office, thus the title of the book. Especially poignant is the narrative at this point in the book as Kennedy tells Gil from the land of the dead,

Where there’s strife and injustice, and nations lose their peace, where people are not free to speak their mind, I’ll lead you with portents and warnings, Gil, a seagull or the clang of a buoy. Where your legions suffer for their rights, I’ll be there with you. I’ll be with you. We begin with peace, Gil. Now, you must leave me.

Life goes on with a physical move away from former cronies, but Gil is far from well. The remaining section of the book reflects his struggles with addiction, mental health and shattered dreams . . . and possibly a way forward through inspirational messages Gil hears from Kennedy whom Gil believes is leading the world to the Millennium of Peace. This is a story of human resiliency set in what would be a tumultuous time in American history.

In real terms, both San Francisco and Berkeley were never the same. Growing up in Berkeley in the ’50s meant awareness of a university central to what the city was. It posed no threat, no students struck or protested, professors taught all classes on campus, the city had yet to confront racism although schools had made moves to integrate kids from the hills with kids from the flats. Much more was to come. It was shocking to come back to what had been a sleepy but academic town from a relatively isolated life thousands of miles away on a distant continent. Turmoil was everywhere as thousands gathered for hippie love-ins, often disrupted by violence and much more. Welcome to the ’60s. And Siegel lays it out for readers to not only read but to see, feel, remember, learn about and be astounded at the tragedy of human beings sinking deeper and deeper who struggle terribly both physically and emotionally to survive.

•

Susan Hoyt Aiken (Ethiopia 1962–64) lived in Oakland for many years raising family, attending graduate school, volunteering in the community, starting work as a career counselor working with adults in transition, directing a graduate program and conducting career workshops specifically for attorneys. In 2004 she moved to Paso Robles on the Central Coast of California to live in co-housing for 12 years. She now resides in the beautiful Valley of the Moon, in northern California, made famous by Jack London. Susan volunteers at Jack London State Historic Park and Luther Burbank Home and Garden located in Santa Rosa.

Dreams, nightmares, a great price, new US brands. Still our people achieve where life’s taken us, continuing to regain wonder finding new roads to old goals. Some days appear cherry-apple-red, fierce amid blank,ugly times, hot, dry, windy.. Pressing on.

Edward Mycue says:

September 21, 2015 at 11:56 am

We had “high hopes” (hear it now, a song sung later than those early days. which are now slathered on the heap history becomes) —

–the “high hoping” that emerged after WW Two through the 1950’s that should/ may/ might yet be explored, explicated, diced, cremated.

What bright faces the now old photos from the early years show.

When we were young, we were apprentices beginning our lives.

I began being attracted to the idea of the APPRENTICESHIP as a description of a life journey after reading the Lincoln part of Josephine Miles’ poem “For Magistrates” that was first published in her last book, the COLLECTED POEMS 1930-1983..

(Connected to this was the Confucius admonition not to conflate error and thus turning it into a crime.)

“For Magistrates” is BY FAR the longest poem Jo would publish.

Here are lines about Lincoln (though it is a poem most fully all together to complete the meaning — and perhaps she was still in process of simplifying it when she began to fail and see her end).

” – – – – – – – – – – – -………………………………….

Shaving, an uncle asks,

What is this face before me in the mirror?

Look well, children, for you see

A face that may grow handsomer every day.

Not Alger, not Narcissus in the stream.

—

Gazing at it, would the martyr ghost

Returned from the grave

Ask, Is this the face I shaved?

As we search the photographs, bearded to full-whiskered,

We watch a man not yet forty

Who might be years younger

Develop into an ageless ancient, which indeed his secretaries

called him

He would be considered no worldly success till late in his

career

But his many failures read

Less as mischance than as apprenticeship.

The superiority of Abraham Lincoln over other statesmen

Lies in the limitless dimension of a conscious self,

Its capacities and conditions of deployment.

In 1863 Walt Whitman watched him

During some of the worst weeks of the war.

I think well of the President. He has a face

Like a Hoosier Michael Angelo, so awfully ugly

It becomes beautiful, with its strange mouth,

Its deep-cut crisscross lines,

And its doughnut complexion.

Suffering endured stoked his energy

With penetration and foresight, often hidden from contemporaries,

Visible

Through restored photos.” (“The Magistrates”, pages 247-253)

REPLY