Peace Corps Lions of Ethiopia

by

Ted Vestal (Ethiopia Staff 1964-66)

•

The pilot, Captain Paul Wuhrman, was glad to be back over Europe. On the horizon he could see some of the snowcapped mountains of his native Switzerland, neutral, alpine orderly. It had been a long haul flight in Globe Airlines twin-engine turboprop Dart Herald. Before starting with an early morning departure in “the Big Rains” of Addis Ababa in the highlands of Ethiopia, Wuhrman had looked in at the neatly stacked cargo in the fuselage and assumed all was in order. He took his place in the cockpit and started up the Dart 527 engines. The engines roared and the winds buffeted, and he took off from the runway of Haile Selassie I International Airport, popularly known as “Bole” sitting at an altitude of 7,500 feet. Wuhrman flew over the rocky north of the country following the path of the Blue Nile, a route that took him above the sere Nubian Desert of the Sudan that eventually merged with the yellow-orange-hued Sahara of Egypt, and then he jagged westward to pass over the northeastern tip of Libya before crossing the bluest of blue Mediterranean to the Boot of Italy. There in the more familiar and more crowded airways of commercial airlines, the Swiss chartered flight was scheduled to land at London’s Heathrow after seven-and-a-half hours in the air.

For such a flight, Wuhrman, 36, was fond of the Herald which had a roomy cabin and flew like a dream. The plane was very stable in the air and highly maneuverable even at slow speed. Wuhrman chatted amiably with his fellow Swiss copilot Max Schomenberger, 25, as they cruised at an altitude of about two and a half miles at 275 mph. The pilots admired the clouds adrift in the summer sky, a congregation of white magically lighting up the acres of azure surrounding them. The Swiss crewmembers epitomized their homeland—orderly airmen of controlled reserve. They were flying over St. Nicholas in northern Belgium, with clear weather ahead to London. It looked like a pleasant trip ahead.

Abruptly, Wuhrman’s reverie was disturbed by something warm and wet nuzzling his leg. He looked down to see a lion with full mane staring at him.

He turned around and saw the heads of two other lions peering through the curtain between the cockpit and the fuselage. The door between cabin and fuselage had not been locked properly and had swung open during the flight.

“Herr Gott!” he cried while grabbing the mike of his radio and calling Brussels on the international emergency frequency. He asked permission to make an emergency landing. “I have three lions in my cockpit,” he shouted. Thinking it was a joke, the control tower responded: “Just stick them in your gas tank.” Frantically, Wuhrman tried to convince the tower there really were three lions in the cabin. He put the radio microphone near one of the lions and coaxed a roar out of him convincing the tower that he was not joking. It was now code red, and Wuhrman was given a top priority landing.

Meanwhile, Schomenberger, wielding a fire axe, was able to push the foot fetish feline back into the hold. The co-pilot swung a third seat in the cockpit around to block the lions who growled but disappeared back into the fuselage.

While this was happening, Wuhrman felt he was setting a new record time by diving straight down 14,000 to 500 feet. “Never have I done it so quickly,” he recalled. “I was told I made a bad landing, but I do not remember much about it.” It wasn’t pretty but the plane was safe on the landing strip. Pilot and co-pilot fled through the cockpit emergency exit, and gendarmes sealed it with a net. “We were in a cold sweat the whole time.”

In the blink of an eye, a lion’s aspect had appeared to Wuhrman who felt like the narrator of Canto I of Dante’s The Inferno:

The lion made his “veins and pulses tremble . . .

He seemed as if against me he were coming

With head uplifted, and with ravenous hunger,

So that it seemed the air was afraid of him.”

Wuhrman should have remembered his Hemingway: “The lion is a fine animal. He is not afraid or stupid. He does not want to fight . . ..” Maybe time for philosophy later. For now, the pilots were on the ground. The lions were on the plane.

•

In 1966, the Wigtons, Bill and Alison, were finishing their second and final years as Peace Corps Volunteer teachers in Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. They lived in a pleasant chicka house that had a neat, whitewashed appearance belying the fact that the walls were made of mud, straw, wood, and manure rather than plaster. A tin roof covered their two bedrooms, living room-dining room, one bath, and kitchen layout. As urban dwellers, the Wigtons had running water and flush plumbing in the house — the main distinctions between their housing and that of their provincial Volunteer colleagues. They cooked on a stove fueled by bottled gas bought from a nearby AGIP service station. The couple had a vegetable garden and several flowerbeds that provided colorful blossoms throughout the year. They converted a separate garage into horse stalls. Their lot was fenced with wooden stakes that kept Wigton animals in and others’ out.

The Wigton’s home was just a short distance from Jan Hoy Meda, the Imperial Racing Club, site of horse races, polo matches, and numerous festivals, sacred and profane. The Wigtons taught at schools near Sidist Kilo, within easy walking distance of their home. Bill taught math at the Haile Selassie University Laboratory School, and Alison was the only PCV kindergarten teacher, working at Medhane Alem School, where she picked up a different sort of Amharic vocabulary, sometimes semi-scatological, talking with six-year olds.

In their walks to and from school, Bill and Alison passed by the Imperial Zoo near the Old Palace. The zoo, founded in 1948 by Emperor Haile Selassie, was unique among the world’s tiergartens since it housed only one variety of animal — the lion. Its ten cages housed a unique kind of Abyssinian species Panthera leo roosevelti (the name came from a lion presented by Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia to U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt in 1904) or Leopantels Abyssinica. Could there have been a more appropriate type of zoo for the country of the Lion of Judah (one of the throne names of Emperor Haile Selassie), whose flag and national emblem were emblazoned with the King of Beasts? The zoo lions’ roars, those mighty shows of power among the males, were an awesome sound that could be heard five miles away during the night. How exciting and adventurous to go to sleep to the serenades of the lords of the jungle, a romantic phenomenon duly reported in PCVs’ letters home.

Less regal were the haunting nocturnal “jaroop” yelps or whoops of the city’s sanitation workers . . . the spotted hyenas that cleaned up around town providing an animal waste disposal service — and a different timbre in the nocturnal harmonies.

Other Peace Corps Volunteers called the Wigton’s abode “Animal House” because of its menagerie of two horses, Kalif and Pepper; a female dog, Zaffon, with seven pups; and four tropical birds, Oriolus Meneliki. The Wigtons found their combined Peace Corps subsistence allowances sufficient for the owning and care of pets as well as living in a manner to which they quickly became accustomed.

Bill had grown up in an Ohio home filled with pets, so he was used to having animals all around, and Alison had taken riding lessons as a youngster in New Jersey and especially enjoyed riding her horse in the Meda and in the nearby countryside.

Dik-dik, photo: wikipedia

For some time the Wigtons had talked about getting a typical African pet, such as a monkey or a dik-dik. Their interest was heightened when Bill heard that occasionally lion cubs were available for purchase at the zoo. He conferred with Gatachew, the wizened caretaker of the zoo, who, for some baksish [money], would prod sleeping lions into action for the tourists with cameras. Gatachew informed Bill he could purchase a pair of month-old male lion cubs for 200 Birr or about $50 U.S. each.

The Wigtons knew that their neighbor, Jane Campbell, an Associate Director of Peace Corps/Ethiopia, was interested in getting an indigenous pet too, so they immediately contacted her and were delighted to learn that she would like to have one of the cubs. The Wigtons also knew it would not hurt to have a staff member on their side should the officious Peace Corps/ Ethiopia office object to their having such pets.

The next day, Bill visited the zoo and paid Gatachew in cash for two male cubs from the litter of Bazoonmish who had once lived in the Emperor’s Palace.

The cubs were in the cage with their mother. A zoo attendant adroitly separated them. Wigton then carefully lifted the cubs by the scruffs of their necks to put them in the wooden Melotti Beer box he had brought along to carry them home. They looked like sturdy tawny stuffed animals with thick disproportionally heavy paws, straight tails and remarkably well shaped heads. They stood about a foot high and had a variegated skin covered o’er with dark leopard-like spots on their heads and lighter spots on their bodies.

As Bill was leaving the zoo to hail a taxi on Russia Road, the cubs’ mother gave a farewell roar when he passed her cage. Her anguished cry set off the other twenty lions in the zoo, and the din could still be heard when Wigton reached home fifteen minutes later.

Bill squeezed into the back seat of a Fiat Ciencentto cab along with two young Ethiopian girls who were horrified when they saw the content of Bill’s box. The cab driver thought it all very funny and broke into laughter. For the girls, it was no laughing matter, and they were visibly relieved when the crazy “ferengi” [foreigner] with the lions got out.

Jane, along with Alison and her household staff, enthusiastically greeted the new feline arrivals who returned their hospitality with hissing and spitting. Nothing lasted long however because the cubs slept for twenty hours at a time and were awake for only four. Jane and the Wigtons agreed that they would be joint owners of both cubs, but that Jane would keep one at her house and the Wigtons would provide a home for the other. Since Jane frequently traveled outside the city, the Wigtons offered to keep her kitten while she was away.

Jane took the larger of the two and named him “Percy,” a name “that just came to her” when she first saw the cub. The Wigtons called their cub “Olaf” in honor of the King of Norway who had come to Addis Ababa on a state visit only the week before.

Initially, the cubs were afraid in their new surroundings and refused to drink from baby bottles of milk or cod liver oil, their only source of nourishment during their first day outside the zoo. By the second day, however, hunger overcame fear, and they drank and became more sociable with their human companions. They wandered around the house like playful kittens. Eventually, they preferred meat, and beef, lamb heart, and liver became their staples. While consuming his protein, Olaf assumed what became his preferred eating posture — down on his belly, his paws completely encircling his plate when they were not ripping the meat, his eyes distrustfully watching any other creatures in the area.

Olaf made friends quickly. Zaffon, the Wigton’s she-dog, had inspected Olaf quietly upon his arrival and adopted him as one of her pups. From the start, Zaffon showed a positive motherly affection and guardianship for the cub. A few days later, the seven puppies, let out of their coop, scampered to meet their new brother. They charged with wagging tails and Olaf gracefully accepted his initiation into the pack.

Zaffon, who was of unknown Ethiopian lineage and stood about as high as a Welsh terrier, played with Olaf as though he were a son, and Olaf treated the pups like younger brothers. Never once during the six months they were together did the cub hurt any of the dogs. At nursing time Olaf even joined the litter, although the Wigtons doubted he derived much from his efforts. The dog-lion relationship in the compound gave credence to the Ethiopian tale that lions would never attack, kill, or eat a dog.

Olaf had a much different relationship with the horses. In his first two weeks he was constantly stalking them while they stood in their stalls in what had been a garage, or while they were out in the yard being washed. These attacks ended either with Olaf being distracted or with him rushing savagely at the stalls only to veer back into the flowerbed at the last minute. With each attack, he got bolder and finally entered into the presence of Kalif, the handsome chestnut stallion. Was his timing bad, entering the stall at the worst possible moment or did his presence evoke an atavistic fear in Kalif? Whatever the cause, just as he ran between the horse’s rear legs, he was hit by a powerful golden stream which sent him in disorderly retreat. Thereafter, Olaf lost interest in equine stalking.

Olaf and Percy were brought up in different ways.

Alison with Olaf in her kitchen

Olaf was a house cat but one that was never babied. Within three weeks and after frequent spankings with a broom he was housebroken. Thereafter, he was allowed to sleep at the foot of the bed. To herald the new day, Olaf would lick Bill’s face with his scratchy tongue. He never purred although he would rub up against Wigton legs like a kitten when he was happy. When reprimanded or swatted with a broom he would slink away to a corner to hiss and growl. At night, when he heard the familiar sound of the lions roaring at the Imperial Zoo, Olaf would strut about the room making faint answering noises, infantile growls and snarls, communicating with his wild kin for reasons the Wigtons could not decipher. Basically, Olaf was a social animal. He liked the people who lived or worked in his compound, and he frequently befriended guests.

In contrast, Percy was an outdoorsman and his coat was always heavier than Olaf’s was. Jane tried to keep him in the house initially but, since she was home much less than the Wigtons, she made little progress in getting him housebroken. After a couple of weeks, she gave up and put him outside. At the same time, she threw out her short gold and beige upholstered couch that had been Percy’s favorite resting place and relief station. The couch was kept on the back porch where Percy often napped in the sun. Although he never wet his bed again once it was in the open, it was still unpleasant to stand too near the couch even after three months of aeration.

In contrast, Percy was an outdoorsman and his coat was always heavier than Olaf’s was. Jane tried to keep him in the house initially but, since she was home much less than the Wigtons, she made little progress in getting him housebroken. After a couple of weeks, she gave up and put him outside. At the same time, she threw out her short gold and beige upholstered couch that had been Percy’s favorite resting place and relief station. The couch was kept on the back porch where Percy often napped in the sun. Although he never wet his bed again once it was in the open, it was still unpleasant to stand too near the couch even after three months of aeration.

During his hearty alfresco living, Percy was mercilessly pampered by Jane when she was home. He was cuddled and petted and, since he could not do much damage to anything outside except the discarded sofa, he was seldom scolded.

Since the Ethiopian servants had virtually nothing to do with him, Percy developed into a one-woman cat. He was much more distrustful of society than Olaf, and the Wigtons were the only people besides Jane that Percy would warm up to.

Percy and Olaf in Wigton house

When they played together, the cubs reminded one of a pair of kittens. Their low-slung bowlegged walk was the epitome of awkwardness, yet there was stealthy grace in their movements when they pursued a bird or some imaginary foe. They wrestled together, sometimes with Zafon and the pups, although the latter got tired of being mauled as the cubs got older. They also played a variety of tug-of-war in which one cub would grab the other’s tail and pull him backwards. When they were very small their distance judgement was frequently faulty and they would leap from the porch into a bush instead of over it. They did leap over catenaries, and left their pugmarks in the mud. One of their favorite playthings was an old automobile tire suspended from a tree just high enough to challenge a cub to jump through it and yet low enough also to serve as a target for a full-scale claws and jaw attack of a rubbery prey.

The Wigtons frequently enjoyed reading while sitting on the grass of their front yard. These occasions provided Olaf an opportunity to sharpen “the affright that from his aspect came” and to practice his stalking skills, undetected, he thought, by the humans. Summoning his wild beast instincts, the cub, light and swift exceedingly, would study his prey from the shade of the house before trotting heavy, big-footed behind his masters. Thirty-five feet into the grass the little lion would flatten out along the ground, all of his strength tightening into an absolute concentration for a rush . . . then, the caprice of the cub: he would get up and slink away as if to say, enough of this feral fantasizing.

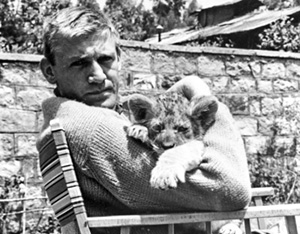

Bill with an armful of lion (Olaf)

Bill often took Olaf to Jan Hoy Meda Square where he could really run free. The horsemen always did a double take when they saw Wigton with his arms full of lion.

The cubs became popular subjects for American photographers — especially PCVs shooting the lions in the slide format popular at the time. “Olaf Couchant,” a portrait of the little king of beasts lying with his body resting on the legs and the head raised was in several collections. “Two lions couchant” was even better.

While he enjoyed his romps, like most cubs Olaf liked sleep, taking cat naps whenever he felt like it. As lion experts note: “A lion is very lazy. The only time they get up any speed at all is when they are very hungry and they see their food. Otherwise, they are lying down.” Olaf’s favorite napping place was in the sun on the front porch. There he would doze, stretched out on his tummy with his rear paws together and his tail in the air. At other times, he slept curled up by Zafon, sometimes with his head lying across her bushy cauda.

It was during his long daytime siestas that Bill was able to clip Olaf’s nails. Lions have sharp claws from the day they are born, so it was a relief to know that his pet’s talons were not dangerous when he romped and lolloped after visiting children or gave Bill a playful right to the jaw. Jane was not so lucky with Percy who managed to give her a light claw scar down her left cheek as the result of a bath accident.

Human response to the lions was varied. Taddella, the Wigton’s zabanya [guard], thought Olaf was a most wonderful creature, and he became the cub’s special guardian. As a keeper of lions, he seemed to gain new respect among the servants of the neighborhood and in the bars he frequented. Simanish, the cook, took special interest in Olaf’s feeding, and assisted Alison in housebreaking the cub. On the other hand, Jane’s zabanya was scared of Percy from the first. He kept his distance from the cub, and when he did have to handle Percy he was wary and somewhat rough.

Visitors to the Wigton or Campbell compounds found the cubs to be loveable and amusing. The barely three-year old Charles Vestal, son of a Peace Corps Associate Director, was playfully chased by the three-month old Olaf. Neither of them was all that steady on his feet, but each knew his role. “He’s going to eat me up!” shouted the man-child as he escaped the pursuing feline. No one was hurt, but some present thought they might die laughing.

Other Peace Corps Volunteers, while admiring the lions, were sure the owners would not be able to keep them or that, if they could, they would have trouble getting rid of them when they left Ethiopia. These expressions of jealousy were irritating and when the director of Peace Corps/Ethiopia, Don Wilson, told the Wigtons that he was coming by to see the cubs they wondered if the predictions were true. Wilson, a lanky, blonde, Wall Street lawyer, on leave from his firm, talked to them mainly about their teaching as they watched the lions play. To their surprise, his only comment about the cubs was, “they’re pretty cute.”

The lions were the favorite topic of conversation on the Peace Corps grapevine during the six months the Americans raised them. There was speculation as to what the owners would do with the cats when their two-year assignments were over in July. Returning the lions to the Imperial Zoo was not an option for the owners. Being cooped-up with other lions would have been a cruel punishment for the spoiled free-roaming cats. One rumor had the Peace Corps erecting a zoo-like enclosure at its Casa Inches headquarters to house the lions who would become the official mascots of the organization. Another theory bruited around was that Jane planned to fly the cubs back to the United States as the nucleus of an African game preserve. Bill investigated returning the cubs to the wild when they were old enough to fend for themselves, but he realized that it would take quite some time to painstakingly teach Percy and Olaf the skills they would need to survive in the wild (as had been done with Elsa of Born Free fame).

Actually, the Wigtons hoped to sell the lions to an embassy when they departed in July. They had seen the German Ambassador’s pet cheetah stalking around the embassy’s tennis court, and they assumed that there would be other pet lovers among the Addis Ababa diplomatic corps. Bill’s preliminary investigation revealed that there was no interest in lion cub buying by the staffs of the various embassies, although the Germans wondered if the PCVs would like to take their cheetah.

Percy and Olaf had continued to grow and fill out and were losing their cubby appearance. When the males stood on their rear legs with their front paws on Bill’s shoulders, they looked their six-foot tall human master straight in the eye. They would add another four feet to their length as they matured. At 6 months, Percy, the larger, weighed a hefty 78 pounds, while Olaf was a slimmer 60 pounds. Fully grown male lions weigh in at around 420 pounds, so the cubs still had some growing to do.

No one in the city expressed interest in taking in two half-grown lions. Meanwhile, a third member of the Peace Corps leonine clowder appeared when Jane purchased a new cub, Little Sheba, from the Imperial Zoo. The keepers already had her pegged as adventurous, fearless and often the first to try something new. In her first night of Peace Corps captivity, Little Sheba stayed at Jane’s where Percy and Olaf already were happily ensconced. Jane was not sure how Sheba would be received by the other two lions. After a night of her crying by the door, Sheba was let out to join the other two in the backyard, and Jane found her shortly thereafter inside the lion lean-to squeezed between Percy and Olaf who were keeping her warm and safe. Thus occurred the Addis Ababa Leonine Concurrence. Borrowing from mathematics where a concurrence is a point at which three or more lines meet, Jane’s backyard was a point at which three or more lions met. After that, Little Sheba resided at the Wigton manor while Percy and Olaf remained with Jane.

In the Spring, as the academic year and their Peace Corps service neared their conclusions, Alison and Bill seriously began to worry about what to do with the cubs. Was there a deus ex machina coming down the rocky road from Mount Entoto?

Help came instead from a different direction. To the rescue, and to the relief of the Americans, came a British knight mounted upon a splendid dark thoroughbred stallion, Theodore, 17 hands. Among their many activities in the horsey set of Addis Ababa, the Wigtons taught riding classes on the stately lawns of the British Embassy. The British Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, Sir John Russell, Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order, enjoyed riding with the Wigtons and admired their instructing youngsters in equestrian arts.

At the end of one session, Sir John rode up beside Bill and told him, “Someone is coming to Addis Ababa who wants lions.” Sir John was referring to Henry Frederick Thynne, the 6th Marquess of Bath, who was buying lions for his new game preserve at his family estate, Longleat, in Wiltshire, England. Bill said he would like to meet the Marquess (though he never did).

Longleat House, home of Lord Bath

The Marquess held noble proprietorship of the 130-room 400-year-old ancestral home. In the 1960s, the immense Elizabethan mansion Longleat had been threatened by inheritance and income taxes, and the Marquess had hit upon a novel scheme for saving the old homestead. “I thought of letting rooms to overnight guests, but that has become commonplace in the castles of Britain” he said. “So, since I have always been enchanted with East African game preserves, I’ve taken it upon myself to give other Englishmen the privilege of seeing the King of Beasts, if not in his natural habitat, at least with a great measure of freedom — and on British soil.”

The Marquess, an accomplished forester, had set aside ninety-seven wooded acres adjacent to his 7,000-acre family estate near Bath (2,000 acres larger than Highclere Castle in Hampshire of “Downton Abbey” renown) as his lion park and had erected a fourteen-foot-high fence around it. The Longleat Safari and Adventure Park, Europe’s first, formally opened on 5 April 1966 with tourists and half a hundred carefully chosen lions in attendance. For a pound sterling per person, visitors could drive about the enclosure — with their windows up — as long as they wished. Every day each lion was fed a beef head from a nearby slaughterhouse, and with such a diet their human visitors must not have seemed appetizing for there never was an untoward incident involving paying guests on the estate. In the winter the lions took refuge in real and artificial caves around the property.

Not everyone liked the Marquess’ scheme. The Times of London thundered: “This is one of the most fantastically unsuitable uses for a stretch of England’s green and pleasant land that can ever have entered the head of a noble proprietor.” Tourist attendance and happy memories of the experience soon belied The Times’ grim diatribe. “How dare you malign my lion!” saith the Lord.

On his lion-buying safari in East Africa in 1966, the Marquess had sought the advice of Ambassador Russell about possible sources of animals. Russell also was a friend of Jane Campbell’s, and he told Lord Bath about her seeking a new home for the Peace Corps lions. When the Marquess, a tall thin gray-haired man who looked like an English nobleman should, came to Addis Ababa, he met with Jane (Alison and Bill were busy teaching and could not attend the meeting) at her home to see the cubs and arrange for them to join the growing menagerie at Longleat.

Previously, Lord and Lady Bath had been royally received by Emperor Haile Selassie at Jubilee Palace, and ten black-maned lions, all of them hand-reared around the Imperial Palace, were on their way to Britain. The Emperor’s private collection of lions was second only to Longleat’s in size. With the Emperor’s passel of Panthera leos and Lord Bath’s gang of lions together, Addis Ababa was the world’s leonine ganglion (defined in some British dictionaries as “a center of intellectual or industrial force, activity, etc.”).

Emperor Haile Selassie in Bath, 1936

Emperor Haile Selassie had known Lord Bath’s father, the Fifth Marquess of Bath, Thomas Henry Thynne (1862–1946), and had visited Longleat during his exile in Great Britain when Mussolini’s Fascists had occupied “Abyssinia” from 1936–1941. The Emperor and his family lived in the Italianate two-story Fairfield House in Newbridge, Bath, some 22 miles from Longleat. The Marquess of Bath whose family crest included two lions rampant was an appropriate host to the Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah.

The Marquess had enjoyed the kind of income with which the British nobility maintained their stately ancestral homes. Lord Bath’s magnificent manor built in the early Renaissance style overflowed with Old Masters, family crests, precious tapestries, gilt wall coverings, 33,000 books and French and English antique furniture. In 1949, the Marquess shocked the British peerage when he opened his mansion to the paying masses — a desperate move to keep the estates whole and in the family. He and Lady Bath moved into a woodland cottage, Mill House, at Longleat, to avoid the castle traffic.

Jane told Lord Bath that she worried about their pet cubs being mistreated in transport or at Longleat. They are “completely tame and friendly,” she explained. The Marquess assured her that the cubs would be well-treated, but still Jane agreed to give the lions to the Marquess only on four conditions: 1) every day two bottles of milk would be given to Percy; 2) every day one bottle of cod liver oil would be given to Olaf; 3) automobile tires would be provided for them to play in; and 4) a particular person would be assigned to help the cubs adjust to their new locale and to play with them at least 30 minutes each day. The Marquess happily agreed to the conditions, and he and Jane made plans for the shipping of Percy, Olaf, and Little Sheba to England.

Bill took Olaf to his veterinarian, Dr. Makkonnen, to receive the required vaccination for transport to Britain. Makkonnen obviously was afraid of the cub and complained that lions could not have rabies. “What creature would be foolhardy enough to get close enough to a lion to give it rabies?” he asked.

Bill held Olaf and tried to keep him calm while the vet attempted to stick a hypodermic needle in his neck. Makkonnen tried three times to pierce the thick skin of the cub, but it was impregnable. Olaf became more agitated with each stab and gave Bill a painful claw cut for his efforts. “Enough!” Bill yelled as he dropped the cub to the floor. The vet and client gave up on bearding the lion, and settled for a document saying the three lions had been vaccinated.

The Wigtons completed their Peace Corps teaching assignments and bade their pet lions sad farewells before leaving on a trip home to the U.S. via Egypt and the Middle East. Jane was left in charge of the lion family and made preparations to have them flown in mid-July to London’s Heathrow Airport.

Dart Herald – wikipedia

On their day of departure, the cub trio were lovingly maneuvered into a large wooden crate marked “Pet Lions,” “Tame Animals,” and “Gentle Pets.” Each was adorned with a red leather collar complete with its inscribed name. Jane drove the crated cubs to the air cargo building at the Haile Selassie I Airport and remained with them, playing with them through the holes in the crates and comforting them until they were placed on the yellow freight carrier and lifted aboard their cargo plane.

The giant cargo-loading door of theplane was closed and the Dart Herald routinely taxied down the runway, was cleared by the control tower, and took off. Jane pondered a mental benediction and thought that she would hear no more of the cubs until the following winter when she planned to stop in London to visit her sister and to tour the estate of the Marquess of Bath.

•

In the cargo hold of the Dart Herald, the three cubs mainly dozed. At last, bored and hungry, they decided to explore their new surroundings. The door of their wooden crate was not firmly shut, so Percy gave it a shove and provided the trio room to step out into the fuselage. They heard human voices up ahead and came to a door left ajar. All they wanted was comfort and human company. Percy passed through the open door and spying the foot and leg of a human, sought to say hello to the pilot. He extended his friendship to him by playfully licking a boot. Just behind him, Olaf and Little Sheba peering through the curtain between the cockpit and fuselage, watched for the reactions of the men. One yelled while the other took a swing at them with what appeared to be a short pole. Somehow all three of the cubs were herded back in the fuselage by a man who pushed a chair across their entry way blocking their entrance.

At the Brussels Airport, police armed with machine guns and firemen with axes and water hoses watched in silence as a slim Dutch zoologist of the Antwerp Zoo, Agatha Gyzen, 50, armed with a broomstick and a nylon net stealthily climbed aboard the mesh encircled Globe Airlines plane. She opened the plane door a bit, poked her head in, and called “What’s new, Kitty?” She came out holding the smallest of the three cubs by the scruff of the neck and lifting her from the plane. Gyzen returned for the larger lions, but they showed no interest in leaving and forced the zoologist into hasty retreat. She called her 100 emergency phone number for reinforcements and said she would make a second attempt to remove the lions later.

Help soon appeared in the guise of zoo attendants from Antwerp, who joined Gyzen in coaxing the trio of lions back in new crates. “You have to know how to handle them and there is not too much danger,” Gyzen said.

She could speak with authority, for shortly after the plane had landed, the BBC somehow had picked up on the story and reported that “three dangerous lions . . . broke out of their crates and threatened to maul and possibly eat the crew.” Fortunately, among the BBC Radio’s listeners was Roger Cawley, manager of the Longleat Safari Park, the ultimate destination of the former Peace Corps lion cubs. Roger got on the phone to Brussels and fortuitously spoke to “a lady zoo director who soon had everything sorted out, explaining to everyone who would listen that they were harmless cubs.” Her message was relayed on to Gyzen just as she was boarding the plane to meet the unexpected leonine guests at the airport.

“Three lions in a cockpit” quickly was written up and distributed by United Press International and became a worldwide front page newspaper story. The narrative got expanded in each telling. The size of the lions was baffling. If Ms. Gyzen could carry the smallest by the scruff of the neck, the 21/2-months old could not have been that large. The two others were described as “full grown Ethiopian lions, each weighing about 175 pounds”— a gross exaggeration. The males were 9 months old, far from full grown. The larger weighed about 80 pounds, his brother slightly less. All three of the lions together might have weighed 175 pounds. Their ferocity was subject to hyperbole too. Some versions described the cubs as “huge beasts.” Lord Bath tried to correct misconceptions. The beasts “are small in size, they are hand bred and have been running around in a garden. They are not fierce,” he said. They were to join 50 lions of the Marquess’ leonine ménage who had been roaming the well-fenced estate, Longleat in Wiltshire, since the park had opened four months earlier in early April 1966.

Happily fed and recaged, the cubs flew on to London later that day in the same plane that had carried them to Brussels but not with the same crew. They landed at Heathrow where they were met by Mary Chipperfield, the lion authority at Longleat, who escorted them overland to Plymouth, 216 miles to the southwest where they were to remain in quarantine at the Plymouth Zoo for six months.

Jennifer Coombes at Plymouth Zoo with Little Sheba, Percy, and Olaf

In Plymouth, the pet cubs were tended by sixteen-year old Zoo Assistant Jennifer Coombes. She followed the requirements laid down in the transfer-of-ownership-agreement between Lord Bath and Jane Campbell and periodically reported to Jane about how the lions were doing in their new locale.

The Peace Corps lions were encaged with ten other lions from the Imperial Zoo in Addis Ababa that had arrived earlier and were already ensconced in the quarantine section of the Plymouth Zoo. The other Ethiopian lions originally from the forests of Abyssinia were much wilder, older and larger than the three pet newcomers thrust into their midst. Initially there were no untoward incidents among the thirteen lions.

After a few weeks, however, the smallest of the Peace Corps lions [Little Sheba], a somewhat spoiled female, tried to take the food of the emperor’s largest lion. She was attacked and might have been killed had not her two male companions from Addis Ababa bravely charged the big lion and saved her. The little female needed surgery as a result of the attack and walked with a limp thereafter. But she had survived her attempt at taking a lion’s share, le partage du lion, and soon afterwards was able to accompany the other Peace Corps lions to Longleat where new adventures awaited all of them. The caprices of the curious carnivores were to bring them yet more fame.

The Plymouth Zoo, incidentally, had a lion cub history of its own. Bill Marshall, Head Keeper at Plymouth Zoo, delighted in occasionally shocking drinkers at a city pub by bringing lion cubs in to greet locals.

In early January 1967, Jane Campbell and her sister Elizabeth visited London and eventually drove for four hours to the Plymouth Zoo to check on the quarantined Addis Ababa lions. When they approached the ceilinged lion cage, Percy immediately recognized Jane and raised a clamorous ruckus trying to join her. He pressed his body into the unpassable heavy gaged wire barrier. Jane, of course, could not go into the lion’s den, so she sadly beat a hasty retreat and drove back to London. That was the last time that the Peace Corps lions encountered any of their Addis Ababa human companions.

A few days later, at Longleat, Jane and Elizabeth were luncheon guests of Lord and Lady Bath at their residence in the Mill House. They toured the estate and saw where Percy, Olaf, and Little Sheba were to be housed during their breaking-in period. Jane and Elizabeth were among the first Americans to learn of the plans for further expansion of the Safari Park and an increase in the variety of animals to be housed there.

Later in the day, the Americans were guests of Mary Chipperfield, one of the world’s most renowned raisers of lions, at her abode in the nearby Pheasantry, where she had quite a menagerie of her own. Mary had raised one of the first Longleat-born lions, Marquis, a handsome male, practically from a sickly birth to young adulthood. Marquis, the premier lion of Longleat, was about the same age as Percy and Olaf, and the three of them looked very much alike. Mary told the story of the trials of cub-raising at the same time she was playing a leading role in the creation of a Safari Park in her fascinating book, Lions on the Lawn (William Morrow and Company, 1971).

She and Jane Campbell must have exchanged similar tales about rearing a lion cub in the household. Jane remembers Mary having a number of lion cubs in her house. The two ladies were to have yet another lion-related meeting in the late 1960s.

A Peace Corps colleague, Harris Wofford [Country Director/Ethiopia 1962–64), had become president of the State University of New York at Old Westbury, and Jane joined his staff. In New York, she found a lioness, Sheba, in need of a better home. Jane kept the campus-celebrity Sheba at her house. When she learned that Mary Chipperfield was passing through JFK Airport on her way to Palm Beach, Florida, to open a Longleat-like safari park, Jane made arrangements to pass on Sheba to Mary at the airport. As far as we know, Sheba lived happily ever after at the Lion Country Safari.

In mid-January 1967, Mary Chipperfield drove the Peace Corps lions in a safari wagon from the Plymouth Zoo to Longleat, a two-hour trip. She dropped them off at their roomy and comfortable ephemeral enclosure, sturdy temporary cages built into the Wiltshire hills. The Addis Ababa trio spent two weeks in the transitory accommodations, as had the original fifty Longleat lions, before a prearranged release day.

The first such singular event had happened on Monday, March 14th, 1966, when the fifty newly-Britishized beasts emerged from their scattered huts “to nose around the vast acres of the reserve.” On a signal, three prides had bounded out of their cages and headed single-mindedly for the 3,200-yard perimeter of the double-fenced sanctuary. They adjusted quickly to their new environment and soon roamed throughout 97 acres of some of England’s finest woodland. By the time the Peace Corps lions arrived, some ten months later, the open cozy huts were being used less and less by the Longleat pioneers, who preferred to settle out of doors in their own corners of the park.

In late January 1967, the new arrivals, Percy, Olaf, and Little Sheba, having been acclimatized and settled in well in the game park milieu were deemed ready to be free range lions wandering in the preserve as they pleased. In the expanded freedom of their forest reserve, they viewed daytime auto adventurers driving around the roadways and snapping photographs of them through their car windows. The Peace Corps lions adapted to their new home and grew accustomed to following daily schedules — especially feedings from estate trucks.

At this time, Lord Bath and his Longleat Safari Park garnered increased attention from the media. Life Magazine did a major feature on the lions, and a Life photographer caught the “elegant nobleman” descending the grand staircase of Longleat in the company of an adoring Marquis. In the same issue of Life, Olaf and Little Sheba were photographed loping about the grounds behind trucks driven by gamekeepers the Marquess called “white hunters” that carried meals to feeding areas. The Safari Park was an instant money-maker for Lord Bath, and the noble proprietorship, which only a few months earlier had been threatened by Labour Party taxes, was sound in pounds and tourist trade.

In the early years of the Safari Park, a number of motion pictures were shot in the forests of Longleat including some by M.G.M., whose symbol is a lion. The Peace Corps trio were among several Longleat lions featured in the James Bond extravaganza “Casino Royale,” which was partly filmed in the grounds and around the house. As mischievous adolescents, Percy, Olaf, and Little Sheba may have been guilty of petty crimes and capers, but they did no more damage than make off with an occasional windshield wiper from a parked car.

In January 1968, Percy and Olaf turned 26 months old and evinced the mien of puissant adults. They displayed iconic manes that encircled their heads and were physically strong, intelligent, and fit. And they were sexually mature. Their voices had deepened, and they could roar with the best, adding their ominous rumblings to the chorus of the forest. Among the lionesses roaming about the drive-through park were several particularly attractive young specimens. Some of the splendid young lionesses were in season, and Percy and Olaf went out on separate expeditions to prove their lionhood. Did they take pride(s) in their work? We’ll never know. Their success in challenging and displacing other males associated with another pride is unrecorded, but one can speculate that they sired successfully and the genes of these powerful Peace Corps beasts, the pinnacle of the cat world, continue to the present day in the Longleat genealogy. Little Sheba too must have contributed to the gene pool especially in light of female lions living longer, sometimes into their late teens, compared to the males, who on average lived only twelve years. One wishes that the progeny of the Peace Corps lions could be identified among today’s Longleat menagerie.

The Peace Corps Lions made a karmatic circle in spending the remainder of their lives in the heavily wooded vales of Wiltshire. From their royal birth in the Imperial Zoo of Emperor Haile Selassie in Addis Ababa, they went to a more humble but loving environment of benevolent Peace Corps Volunteer owners who could have been accused of spoiling their cubs before flying them from Africa to England on a trip that briefly made the little lions international media celebrities, then depositing them in quarantine with other Panthera leo roosevelti, more plebian than patrician, and finally settling the trio on a grand British estate once visited by Emperor Haile Selassie. There, in the stately groves of Longleat, Percy, Olaf, and Little Sheba slept, ate, and procreated in a basically safe and secure environment for the rest of their days.

In addition to serving with the Peace Corps in Ethiopia in its nascence and encountering Ethiopian history and culture only as one can by actually living in its midst, Jane, Alison, and Bill raised magical lion cubs in their homes — the very apogee of an African experience.

•

Jane Campbell (Peace Corps Staff HQ & Ethiopia 1961-65) enjoyed an international career in government service and education. She received an M.A. from Columbia and worked in the African-American Institute before a 5-year tenure with the Peace Corps in Washington and Ethiopia. She was on the founding staff of SUNY-Old Westbury and then enjoyed an 18-year career with UNICEF. She married a British diplomat, John Lewis Beaven, CMG CVO, whose work took them to more global destinations. They settled in Ghent, NY, where Jane started The Wildlife Center and Great & Small Rescue that rehabilitates injured, orphaned, and otherwise distressed wildlife from throughout New York.

Bill and Alison Wigton returned to the Washington, D.C. area to work and pursue graduate studies. Alison taught in the Prince George’s County (MD) public schools and earned an EdD in Special Education from George Washington University. She had a distinguished career in education until her death in 2014. The Wigtons were married for 50 years.

Bill worked as a Mathematical Statistician in the U.S. Department of Agriculture and received his M.Sc. and was an ABD at North Carolina State University. Working in the USDA’s Research Division for 22 years, he did pioneering studies in the use of Landsat satellites to estimate crop area. He started his own company, Agricultural Assessments International Corporation (AAIC) and did contractual assignments in over 60 countries with such entities as e.g., the UN, World Bank, UNEP, and USAID. While working for the Bill and Malinda Gates Foundation, he went to Ethiopia 50 years after his lion training experiences and revisited the locales of his PCV days. On two different occasions in Khartoum, he serendipitously met Jane Campbell. Today, he continues to live and work in Seaford, Delaware.

Ted Vestal worked in Peace Corps/Washington in 1963-1964 and 1966 and was Associate Director of Peace Corps/Ethiopia in 1964-1966. In Addis Ababa, he was an acquaintance of the three lions in this article. He is the author of Ethiopia: A Post-Cold War African State, The Lion of Judah in the New World, International Education, and “Afterward” Haile Selassie’s Government. In 2018, he received the Grand Cross of the Star of Ethiopia from the Crown Council of Ethiopia. He is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Oklahoma State University and lives in Tulsa, OK, with his artist wife, Patricia, who taught painting at Haile Selassie I University.

I had in my hands a lion cub while sitting on the palace steps of the governor of Tigray in Mekelle, 1965. Mengesha Seyoum was married to Princess Aida, the granddaughter of Emperor Haile Selassie

Prince Mengesha has been a lifelong friend. The first time I met him, he was driving a bulldozer repairing a washed-out bridge in Melelle. How’s that for “hands-on” royalty?

A wonderful reminder of the early Peace Corps when all things were possible. Want to raise a lion? No problem. We were so unconcerned about unintended consequences in those early years.

Those were the days. We were fortunate to have been in “the Kennedy’s Children” era of that great organization.

Hear! Hear!

What a great story and beautifully told.

Wonderful memories Ted. Marcia and I lived in Axum, did not know Bill and Alison but I did attend a gathering at Jane Campbell’s home in Addis one evening. Can’t deny I was somewhat nervous when Percy brushed by me. Jane was a pioneer, so glad to read this story.

Lucky you to be stationed in Axum. Jane was a wonderful colleague in Washington and Ethiopia. It was grand to have virtual reunions with her and Bill while writing this piece.

A wonderful story and fortunately it happened early enough in the Peace Corps experiment so that PC/Washington had not issued an “ukase” barring the owning of lions by PCVs. Peace Corps’ near 60 year history is filled with many fascinating stories and adventures such as these, (as well as a few ignoble ones) and much good work. May the Peace Corps allow room for such good work and adventures for another 60 years!!!

Thank you, John. In the later years of the Johnson administration, Peace Corps people already were complaining about the organization becoming bureaucratized. I second your motion for another 60 years of good work and adventures.

I remember that Jane had a pet lion and wondered what happened to Percy. Now I know. It’s a great story. Thanks for publishing!

I talked to Jane on the phone yesterday about her wildlife rescue operation. She has bobcats and coyotes in her hospital, but no lions. She would prefer them! Thanks for your comment.

Cynthia Ellison Mehary

I was a PCV teacher in Addis Ababa from 1965 – 1967 at Tefari Mekonnen School. This school was located near Sidis Kilo and across from the Emperor’s Palace. Each day as we walked from our home to the school, we would see a Lion walking on top of the wall surrounding the palace. We were fine with this until one day someone told us that the chain hanging from the lion’s neck was not attached to anything. From then on, we really watched that Lion. (smile) Your story about these lions, brought back so many memories. Thanks for telling your story.

I had not heard about the free-roaming lion at the palace. There were two lion stories about Americans at Jubilee Palace in the 1960s. The first time Sargent Shriver visited Emperor Haile Selassie, the Emperor urged him to pet “Tojo” the big male. There were several PC/Washington staff with Shriver on that visit, and they wanted to know the line of succession in the PC organization when Sarge began to massage the lion’s head. A few years later, Bobby and Ethyl Kennedy were in AA for the dedication of the Kennedy Library at HSI University. At the palace, Mrs. Kennedy stroked the lion’s flank. There was no record of Bobby following suite.

What a great story and so well told. Ted, you missed no important detail. Splendid. And thanks to John and Marian for publishing it on their indispensable site. We had few interesting animal stories to tell from Debre Marcos. We once foolishly bought a baboon in the market. He lasted about a destructive week. We had a student take the poor creature for a very long walk and deposit him somewhere far enough away that he would not come back. Of course, many of us had horses, but compared to lions!!, not a story. Again, a wonderful tale. Thanks much, Ted.

BRH

Thank you, Barry. Your encouragement inspires me to write some more tales of PC/Ethi while I can still remember them. A couple of lady PCCs, maybe in Debre Berhan, had a genet cat that would run across your arm while you were seated on the couch. There were a few Dik-diks that survived in PCV homes. Gerry Faust had a Thomson Gazell in AA that ate cigarette butts. Other than horses, dogs, and cats, I don’t remember other PC animals. Happy Groundhog Day! Ted

Dear Dr. Ted,

I am grateful you took the trouble to write this up. You have reminded me of all the great adventures we had and the people we met in Addis Ababa over 50 years ago.

Thank you,