Peace Corps at 60: “Service changed lives of midstate volunteers”

U.S. Peace Corps volunteers raise their hands to swear in during a ceremony in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, on Monday, Oct. 3, 2011. More than 100 Peace Corps volunteers on Monday held the swearing-in ceremony before joining Cambodian villagers in the southern provinces of Cambodia.

“I joined Peace Corps in 1988 to immerse in meaningful work providing basic needs at the village level, as well as an opportunity for an out-of-the-box experience and time to reevaluate my life.”

By Rick Dandes/The Sunbury PA Daily

March 6, 2021 | 1:29 PM

•

At a time when the Peace Corps has suspended all operations due to the COVID-19 pandemic and recalled 7,300 volunteers from 60 countries — a first for the six-decade-old program — six former volunteers with Central Pennsylvania connections recall the value of their “life-changing” experiences and praised the virtues of the far-off locations where they served.

Whether assigned to primitive villages in Africa in the 1980s, emerging democracies in Eastern Europe in the 1990s, or more recently to South America, they all joined the Peace Corps out of a desire to serve their country and to help people in need, using skills they already had or acquired in college.

The Peace Corps will celebrate its 60th anniversary on Monday. Signed into existence by President John F. Kennedy on March 1, 1961, the Peace Corps is a service organization with volunteers usually assigned to 141 countries to work side-by-side with local leaders. The organization, according to its mission statement, promotes world peace and friendship through fulfillment of three goals:

— To help the people of interested countries in meeting their need for trained men and women.

— To help promote a better understanding of Americans on the part of the peoples served.

— To help promote a better understanding of other peoples on the part of Americans.

“For 60 years, the Peace Corps has sent Americans abroad to live and work alongside people on issues of tremendous importance to their daily lives, including agriculture, education, and health,” said Carol Spahn, acting director of the Peace Corps. “We believe that there is nothing more powerful in uniting people around the world than working together in a spirit of partnership. And, we have seen how building relationships in this way can help to build international peace and friendship at all levels.”

Susquehanna University Professor Shari Jacobson, Lewisburg landscape architect Brian Auman, and Bucknell associate director for student learning support Laura Lanwermeyer all served in different African countries.

Gia Ciccolo, a 2014 Bucknell University grad, served in Guatemala.

Eric Martin, now a Bucknell professor, and Teri MacBride, former president of the League of Women Voters of the Lewisburg Area were posted in Eastern Europe at a time when the Soviet bloc had fallen and countries were now emerging democracies.

U.S. Peace Corps volunteers attend the swears in ceremony in U.S. Embassy to Cambodia, in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, Friday, Sept. 25, 2015 as they mark official start of the corps volunteer program in this impoverished Southeast Asian nation.

SENSE OF DUTY

Jacobson joined the Peace Corps, after college, in 1984, out of a sense of duty to her country.

“I was going into either the Air Force or join the Peace Corps,” she said. “By the time I graduated, I spoke French fluently and had a math background as well. I interviewed with a Peace Corps recruiter who was on campus (during her senior year) and I thought that sounded good. Serving my country seemed like a good idea but I wasn’t quite sure how I could do that.”

She had been a math major in college. The Peace Corps needed math teachers in Africa. As soon as the recruiter heard she was fluent in French and knew math, the recruiter said she would be a math teacher in a French-speaking country.

“That was in April in my senior year. And I left for Africa in June. I was on my way,” she said. Her assignment was in The Republic of Congo, then known as Zaire. The first village she lived in, in the eastern part of the country, was Lemera. The second village, where she spent most of her service, was Totshi.

After college, Auman was working in an architecture and planning firm in Philadelphia, designing large-scale commercial projects, and he became disillusioned with it.

“I joined Peace Corps in 1988 to immerse in meaningful work providing basic needs at the village level, as well as an opportunity for an out-of-the-box experience and time to reevaluate my life,” he said. The Peace Corps assigned him to Mali, a village named Babougou-Koroni.

EXPAND WORLD VIEW

Lanwermeyer had wanted to be in the Peace Corps since she was 14, she said. “I had known some people whose Peace Corps experiences had been impactful for them, and they felt they had helped others too. I joined because I knew I had a narrow view of the world and I wanted to expand it; I wanted to support others in what I hoped would be a sustainable way while learning from and living in another culture. I signed up to be a teacher but I knew I would learn a lot more than I taught.”

She was sent to Malawi in 1999. Chileka was her village; it was in central Malawi in the Lilongwe district about 30-45 minutes west of the capital.

Martin had administrative skills that he used in Gdansk, Poland, in 1992; MacBride was in Albania in 2003, where she too was able to use her administrative skills in a country that had gone through a revolution, deposing a dictatorship. Both Martin and MacBride helped newly democratic municipalities deal with non-profits.

“Here I was, just out of college, lecturing mayors and other officials, helping with foreign assistance,” Martin recalled. “Professionally, this was a big growth experience.”

In Guatemala in 2016, at the first home Ciccolo lived in, running water was limited during the day.

“The water would be turned on at night,” she said. “The second house I lived in was higher on a hill and had better access to water and I had electricity. I lived pretty comfortably. You did have to heat your own water, and that was normal there.”

In the location of that second home, she was able to use the internet.

Ciccolo always felt safe. In Guatemala, the Peace Corps had very strict traveling policies.

“There is pretty high security there. We had to report where we were. I did feel welcome,” she said. “I was in an area where there was already a foreign presence. There was a bit of mistrust with the groups that did come in but once I made it clear that I was showing up every day for two years, it became evident that I was not like the other people who came for a week just to do a quick trip. One thing I learned is that real development work, real change doesn’t come from weeklong visits.”

Sargent Shriver, director of the Peace Corps, addresses a group of 200 young men and women nearing completion of a nine-week course to prepare them for service in Nigeria, at Columbia University in New York City, Aug. 19, 1963. Graduates of the course will leave New York for Nigeria on Sept. 10.

MATCHED TO HEALTH

Ciccolo “was very much into public health and it had been what I was studying,” when she decided to join.

“I was always interested in women’s health,” she said.

Ciccolo said she saw a chance, through the Peace Corps, to use her knowledge and help others in her field of interest. “I was matched to health. In Guatemala, by chance, that was where I worked, with midwives, from 2016-2018.”

Ciccolo was sent to a very rural area seven miles outside the capital of Guatemala City, in the western highlands, to a municipality named Chicaman. “It was completely rural, very mountainous, and very beautiful. There were three different cultures there, each with different languages, but all had a Mayan background.”

A majority of births in Guatemala are overseen by midwives — not by doctors, Ciccolo said. “I worked with those individuals, making sure there was good communication between them and the health centers. There was a lot of tension between the midwives and the health centers, the health care system, because midwives are not formally recognized.”

She also conducted empowerment workshops with local women living in the community. Ciccolo, with her skill sets and interests, had been given a choice of countries to go to, and that is relatively new in the Peace Corps. Prior to these changes, volunteers picked preferred regions, like Africa or Europe.

NO MODERN AMENITIES

Ciccolo, Martin and MacBride were in homes that had some modern amenities.

Not so, for Jacobson, Auman, and Lanwermeyer, who were all posted in very poor, rural African villages.

For Jacobson, who grew up in the New York metropolitan area, Long Island, her destination was an eye-opener.

“We were not an outdoors-oriented, camping family,” she said. “I didn’t know anything about living without electricity, clean water. It wasn’t an experience I ever had. It was pretty different for me, being in rural Congo. It was hard. It’s a pretty common story that the first year is hard and people are miserable.”

The east Congo, where she was first sent, had become a hot spot with millions of people killed in a civil war.

“Things were pretty unstable. My post got evacuated and I was moved to the western part of the country,” she said. “Authorities wound up closing down the East Congo.”

Jacobson was teaching math in French, which was spoken in their educational system. But what people speak in everyday life, she said, are a few different languages. One is a regional language and the other is the language of the ethnic group. Basically, anyone in a Congolese village speaks three different languages at any given moment.

“It was very stressful. the first year,” she remembered. “I had never been without running water and electricity. I had never had to use candles, hurricane lanterns, outhouses, carry water, cook on an open fire with sticks. That was all a pretty steep learning curve for me. Plus the language, plus the culture. Plus the scorpions and the snakes, malaria.”

All through the experience, her parents were supportive.

“I was 21 and they understood my desire to be in the Peace Corps,” she said. “My dad and stepfather were veterans so they understood what it means to serve your country. But sure, they were very nervous for me. There was no mail system in the Congo. It was the seventh poorest country in the world when I lived there.”

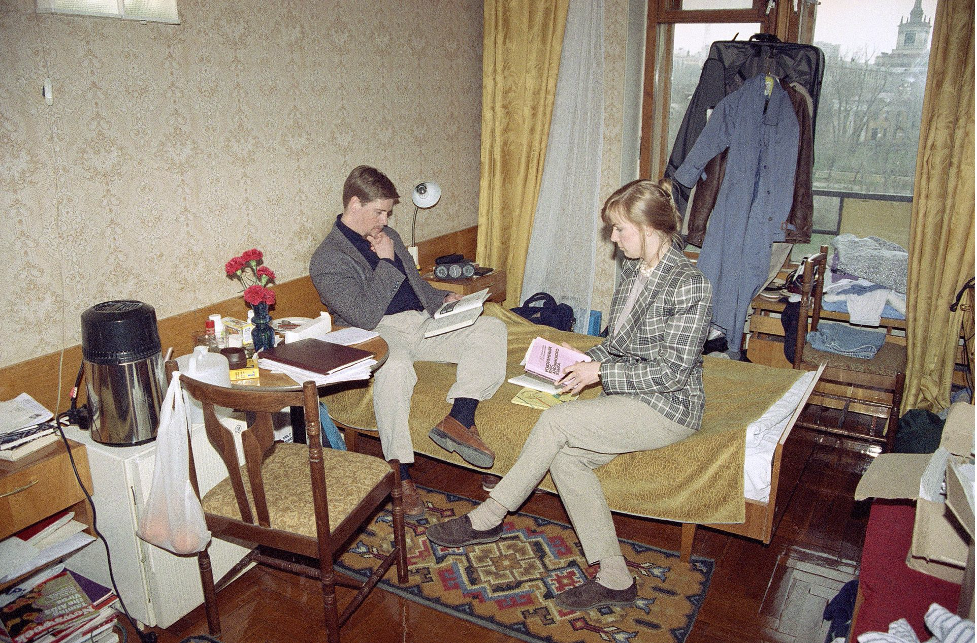

Peace Corps volunteers Kelly Taylor Walker and her husband Robert Walker work and live out of their cramped Volgograd, Russia hotel room, April 27, 1993. The San Francisco couple claim they have not received the resources promised by the Peace Corps business development program, part of an international effort to provide hands-on assistance to Russia.

TREES IN THE DESERT

Mali was also one of the poorest nations in the world when Auman arrived.

He wanted to serve in Africa. Mali is the former French Sudan, and he did speak high school French. But he was placed in a village where not one person spoke French. The language was called Bambara.

“Officially I was an agro-forestry volunteer,” he said. “I planted a lot of trees. I was at the southern edge of the Sahara desert. Fringe desert. So all the cooking is done with wood. Primarily the need of my region was for potable water. A lot of the villages had no access to potable water.”

Auman helped build wells for gardens, food production, and as a village water source.

The village was very remote.

“I was on the edge of the inland delta area,” he said. “There were no paved roads and access was really difficult in the rainy season. I was on the Niger River, so you actually had some boat travel. My village had 75 people and there were probably three ethnic groups represented in my village. The traditional Bambara farmers, the traditional fishermen, and the traditional herdsmen of the region. It was ethnically diverse, but all very devout Muslim. I asked for rural and isolated, and I got it.”

Within a few months, he helped build his own house, a two-room mud home.

“I made it with the local mason from my village,” he said. “That is when I first won them over. It is so hot you tend to sleep on the roof of your house … The walls aren’t radiating heat, you can actually sleep at night. He built the house and I built the stairs. He does it all by gut instinct and I drew it out and did the calculations for the house and that impressed him. It was traditional building methods versus me putting it down on paper first and calculating bricks and the steps calculations.

“I’m a thin guy anyway and I lost a lot of weight there,” he said. “I had three separate bouts of malaria, I had amoebic dysentery, whipworm … And at the end of my time, I got hepatitis from contaminated water. I was in a clinic for over a week and really in pretty bad shape. So I limped home.”

Because his village had no dependable water source, he ended up using Niger River water and treating it with bleach as his main water source.

Mali was a dictatorship when he was there, but Auman said he always felt safe. “People were passive as far as politics. It was a very calm time politically. I have always wanted to go back but unfortunately, a part of the country has now been overrun by branches of Al Qaeda.”

‘PRIMITIVE’ LIVING

Malawi is a former British colony. They needed a science teacher so the Peace Corps sent Lanwermeyer to a remote village of fewer than 1,000 people. Lanwermeyer lived in a cement block house with a cement floor and a metal roof.

“I had electricity six months out of the year,” she said. “I cooked on a gas stove but had to fetch water from a well. I had an outhouse, not attached to my house, in the back yard of my small area.”

She lived on the campus of the secondary school where she taught.

“It was primitive. I was sort of camping,” she said. “I had furniture. I was the first volunteer to ever be assigned to my village so I was given a relatively new house but it was unfurnished. The school provided a chair, a table, and a mattress. I had my local carpenter build me a futon and a couple of other things.”

Lanwermeyer said she felt safe there. “Malawi is a very peaceful, welcoming country. The politics occasionally got heated, but I never felt unsafe in my village. I was protected and welcomed.”

People were so welcoming, she said. “I found that everywhere I went, people were genuinely curious about who I was and what I was doing there.

There is very little infrastructure in Malawi, let alone tourism or visiting from white foreigners. So Lanwemeyer stuck out like a sore thumb.

“But people were so generous. Wanted to share a meal, tell a story, shake hands and become friends.”

______________________________________________________________

REMEMBRANCES:

Susquehanna University Professor Shari Jacobson, says she had to reinvent herself to live in the Congo as a Peace Corps volunteer in 1984.

Her entire experience took a lot of stick-to-it-iveness, she said.

“There was one night when I thought I would leave,” she said. “I had malaria, 105-degree fever, I’m shaking, have a headache, there is a horrible thunderstorm outside. I also had a case of worms and I had to go to the outhouse. Immediately. I lit my lantern and made my way out to the outhouse. Pouring rain. Thunder, lightning. I go to do my business in the outhouse. And I feel like my legs are on fire. I look down and I am covered with fire ants. I look up and it looks like the walls of my outhouse are pulsing. The whole thing is covered with fire ants. I run out of there. Try to brush these things off me, I finally do…make my way back to my house. I am soaking wet. Shaking. Feverish. And say to myself, I am leaving tomorrow.”

She could have left. Peace Corps volunteers can leave at any time. But she didn’t.

Jacobson and other Valley Peace Corps veterans all learned lessons about the cultures in other countries and America’s perception of those countries.

“The people I was with are the most hospitable people in the world that I’ve ever encountered and I’ve also lived in China, Argentina and France,” she said. “These were people who really knew how to live together — really cared about that human fabric. Took care of each other. Shared. Everybody wanted to take care of me. Feed me. They knew I was a stranger. Wanted to send their kids to your house to keep you company.

“It has given me a whole new way of thinking about life. And I am grateful for that,” Jacobson said.

Time spent in Mali while serving in the Peace Corps also changed perspective about what’s really important and much more for Lewisburg Landscape architect Brian Auman.

“People are essentially the same the world over with a shared humanity,” he said. “There is much more that connects us than divides us. Living in a small village of subsistence farmers on the edge of the Sahara desert gives a unique perspective on sustainability, resilience and living in balance with the natural world. Those two and a half years were a gift that changed my life forever.”

Auman realized there is brilliance at different levels in different cultures.

“I was just awed by their adaptability to a harsh environment and also their warmth and hospitality and openness. At the time the World Bank had Mali as one of the five poorest countries in the world. You would never know it. The hospitality you were shown as a foreigner, as a guest. It just puts us to shame.

“It was quite the epic adventure,” he said.

Laura Lanwermeyer, Bucknell associate director for student learning support who served in Malawi in 1999, learned how much she didn’t know about the world.

“I learned how much privilege I had taken for granted my whole life. I learned a lot,” she laughed.

Bucknell Professor Eric Martin and former League of Women Voters of the Lewisburg Area president Teri MacBride were along for the exciting ride as Poland and Albania, respectively, embraced democracies.

“I felt very welcome there,” Martin said. “Poles very much respected and loved the United States. There is a strong connection. When I was there, the second biggest Polish city, with polish nationals in it was Chicago. People had been leaving during the difficult times in Poland under martial law. So there was a great affinity for the United States.”

The U.S. poured a ton of money into Poland right after the Wall fell, Martin said. “We wanted to prop up the closest neighbor to the Soviet Union that we had a good relationship with and Poland was a big, important country, 99 percent white and Catholic with a good relation to the U.S. so it was a good place for foreign assistance to go into.”

Even now, MacBride recalls that Albanians were so pro-American … and kind to foreigners. And generous beyond belief.

“I truly appreciated the humanity of everyone working to improve the lives of their family,” MacBride said. “In many ways I learned that people are fundamentally the same around the world. I had a tremendous experience in a country that was evolving and emerging from a state of brutal control. People had lived under a reign of terror for many years. They didn’t trust the government. But they were so trusting of Americans.

“I learned how highly regarded this country is,” she said.

Gia Ciccolo, a 2014 Bucknell graduate, said her Peace Corps service in Guatemala taught her a lot of things as well.

“I learned that western culture makes a lot of assumptions about how other people live. And what the right and wrong ways to live are,” she said. We assume that in other cultures, where it seems that women are oppressed that those women are (for lack of a better term) weak. They are allowing it to happen. But from working with indigenous women in these areas, with very few resources, I realized that they were among the most intelligent, hard-working people I’ve met in my life.

“There was very little I could teach them. It was more a learning experience for me. I hope they learned that people are interested in them. And that we value them as a people, as a culture, and what they were doing,” she said.

As an RPCV, what always impressed me was the hospitality of the people with whom we shared experiences during our two years as volunteers. People who had so little in material terms were sharing and caring in ways we could never imagine and never repay. These volunteers had experiences of that nature even in the face of tremendous obstacles. It is the central point of their varied experiences.