PCV Vanessa Paolella | Letter from Madagascar

Vanessa writes, “The market in Ambalavao, a small urban center in south central Madagascar not unlike Lewiston, offers nearly everything one could need, including household goods, clothes, hardware and food. During my Dec. 6 visit, I bought plastic food containers, a broom, curry spices and a couple of pineapples.”

Sometimes, I imagine I know what it’s like to be Patrick Dempsey.

Everyone stares at me when I go grocery shopping. Making small talk on the street inevitably draws a crowd. Strangers want to take photos of me. Girls giggle to each other when I say “hello,” or, too shy to approach, they instead point and call to me from yards away.

The major difference in my comparison, as I’m sure you might guess, is that no one has graced me with the title of “Sexiest Man Alive.” Not yet, anyway.

That, and my only claim to fame here in Madagascar is presumably being the lone white person for miles. I’m the first Peace Corps volunteer to live in this village and likely the first foreigner.

Being able to hold a basic conversation in Malagasy only draws more attention. Foreigners rarely make the effort to learn Madagascar’s native language, preferring instead to get by with French.

But with plans to live here for the next two years, there’s no escaping the necessity of it.

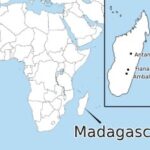

A map of Africa with an enlarged section of Madagascar. The capital, Antananarivo, is marked along with the largest city in south central Madagascar, Fianarantsoa, and a district capital, Ambalavao. Vanessa Paolella

A map of Africa with an enlarged section of Madagascar. The capital, Antananarivo, is marked along with the largest city in south central Madagascar, Fianarantsoa, and a district capital, Ambalavao. Vanessa Paolella

I arrived in Madagascar as an aspiring Peace Corps volunteer in September, excited for a learning experience unlike anything else. Two months later, after intensive language and technical training, I was officially sworn in along with 19 others.

As agricultural extension volunteers, we will be working with community leaders to teach intensive organic farming techniques and nutrition. We’re trying to make nutritious foods more accessible, especially for pregnant women and children under 5 years old.

Madagascar has one of the highest rates of childhood stunting in the world, with roughly 40% of all children affected, according to the World Bank. The first several years of life are critical for a child’s physical and mental development, because without proper nutrition their brain won’t fully develop. Stunted children often struggle in school, become sick more easily and remain in poverty for the rest of their lives due to poor earning potential.

The problem is complex, but education and income are at the crux. Data from the World Bank states that 80% of the country’s 30 million people live on less than $2.15 per day, making Madagascar one of the poorest countries in the world. Most families can afford to eat little more than white rice every meal.

To give you an idea of what that looks like: Buying a couple of chicken eggs in rural Madagascar is not unlike buying steak for dinner in Maine. Eggs are a pricy luxury here, and meat even more so.

While data indicates that the rate of childhood stunting may be improving, food security in the country continues to worsen due to factors including population growth and climate change. The United States Agency for International Development predicts Madagascar will experience higher temperatures and less frequent rainfalls in the coming months due to El Niño, likely exacerbating the problem.

It’s a daunting issue, one that us volunteers can only dream of putting a dent in. For now, we’re settling into our new homes, practicing our local dialects, making friends, and keeping our eyes open for opportunities to improve our communities.

Just weeks ago, I moved to a small village in the southern highlands of Madagascar, several miles outside of a urban center in south central Madagascar not unlike Lewiston. For safety reasons required by the Peace Corps, I can’t say exactly where my site is located

Lemurs at a wildlife park near the Peace Corps training center are well-acquainted with humans. The lemurs don’t hesitate to hop onto visitors shoulders when bananas are offered.

Back in Auburn, I lived in a cushy two-bedroom apartment overlooking the Androscoggin River. Now, my home is a brick house with no electricity, no running water and little more than a single spacious room. Both my front and back yard are fenced in for privacy, and I’m planning to add container gardens and chickens soon.

By Madagascar standards — even by my own, if I’m being honest — it’s a comfortable living situation. Just next door, my host family lives in a house with the same layout. Only instead, three people share the house’s single room. God willing, a new baby expected in March will soon make it four.

My new home looks a lot like the Southwest United States. It’s hot, dry and mountainous, with only a few trees dotting the landscape. I’m still amazed by the miles-long panoramic views I get on my morning runs.

I really like my village, and I really like Madagascar. I knew I would. But living here hasn’t always been easy.

While traveling to visit my village for the first time in October, I puked in my emergency medical kit with six hours of travel left in the day. It was four days before I was able to keep food down again. And because I was running a fever above 101.5, I had to take two malaria rapid tests, which ended up with me stabbing my finger a dozen times in search of blood.

Then after arriving at my new home, I was repeatedly asked to introduce myself to groups of people who soon realized, to their disappointment, that I could offer little more than my name in Malagasy. I’d tell you what was running through my head that day, except it wouldn’t make it past the editors. Suffice to say, I was greatly overwhelmed and spent significant time questioning my life decisions. (Fortunately I got through the doubt and now have a better grasp of the native language.)

But the hardest part of the past three months was undoubtedly waking up to news of the mass shooting in Lewiston on Oct. 25. I couldn’t reconcile the peace here in Madagascar with the terror that friends and family were feeling while sheltering in place. Days went by when I neglected my training and fervently wished I could be home in the Sun Journal newsroom.

A section of the market in Ambalavao, which is a small urban center in south central Madagascar not unlike Lewiston.

Over the next two years, I expect I’ll face more challenges living here in Madagascar. But I know the joyous moments will more than compensate.

I hope you’ll join me in learning about this wonderful country. Every month during my time in Madagascar, I’ll write a column for the Sun Journal describing the country’s unique culture and my experience living here. I’ll write about topics including education, food, religion, travel, shopping, holidays – and Famadihana, a funerary tradition that involves food, festivities and uncovering corpses.

Have I mentioned that the Malagasy people really know how to throw a party?

More on that one next fall. For now, let’s hit the basics.

A MADAGASCAR PRIMER

You probably know that Madagascar is an island off the eastern coast of Africa, located in the Indian Ocean. While it may look small on a map, the country is actually quite big. Overlay a map of Madagascar with the U.S. and you’ll find that the country stretches from Toronto to Tallahassee, Florida. It’s the fourth largest island on Earth, and the oldest.

One of my favorite facts: Madagascar was most recently connected to India, not Africa. The two landmasses split from Africa together roughly 155 million years ago, then later separated themselves.

Due to its isolation, Madagascar’s wildlife evolved separately from Africa and India. Scientists estimate that more than 80% of all species on the island are endemic, meaning they can be found nowhere else in the world. Scientists have identified more than a hundred different species of lemurs on the island, the most famous of Madagascar’s wildlife, many which are now endangered due to deforestation and habitat destruction.

Curiously, little is known about Madagascar’s first human inhabitants, including when and why they first arrived on the island. Estimates range from as much as 10,000 years ago, to just 1,000. What is known, however, is that Malagasy people today have a mixed heritage from both East Africa and Southeast Asia, specifically Indonesia.

Alexandre, a mason, spent several days building the toilet and shower rooms in my backyard in my host community. The toilet hole is roughly 25 feet deep and was hand-dug by other workers weeks earlier.

The Malagasy language is most closely related to the Ma’anyan language spoken on the island of Borneo, located more than 4,500 miles away. It’s generally thought that the first people of Madagascar descended from traders who traveled to the Middle East, perhaps via the East African coast.

Over the centuries, Malagasy has picked up loanwords from Malay, Javanese, Arabic, Bantu languages, and, most recently, French. The language is particularly unique because sentences generally start with a verb and end with the subject. Again, more on that later.

There are 18 officially recognized tribes on the island, all with their unique dialects, physical traits, and cultural traditions. Those who live in the mountainous interior called the highlands tend to have features most similar to Southeast Asians, while those who are from the coast and the south often appear more similar to East Africans. Christianity is the primary religion of Madagascar, however Islam influence is strong in some regions of the country.

Perhaps as a result of their geographic isolation, distinct cultural heritage and linguistic differences, most Malagasy people do not consider themselves to be either Black or African. Rather, Malagasy people often view themselves as a distinct group from those who live in continental Sub-Saharan Africa.

As for me, I’ll be living among the Betsileo people, a name which can be translated to mean “Never Give Up” or “The Many Invincible Ones.” The Betsileo are one of the largest tribes in Madagascar with more than 4 million members.

Since 1993, more than 1,500 Americans have served as Peace Corps volunteers in Madagascar. Today, they support projects in English education, health and food security in communities across the country, working in schools, in health clinics, and in partnership with local nonprofit organizations.

Sunday worship at a Lutheran church in Mantasoa, where the Peace Corps training center is located. Parishioners usually pray inside the nearby church, but the special service on Nov. 12 made it necessary to relocate outside.

Agricultural volunteers in Madagascar work with community leaders to improve food security and nutrition. We help train local farmers in intensive, organic farming techniques and work with mothers to create vegetable gardens. At the start, we work with people one-on-one, but later host workshops after our language skills improve.

That’s the official job description. But to be honest with you, none of us know what our day-to-day will look like, nor will we all necessarily be doing the same kind of work. When I know exactly what I’m doing, I’ll be sure to share.

What I do know is that volunteers aren’t here to single-handedly improve communities in our short two-year stints. Rather, we’re trained to help facilitate critical projects and find the resources to fund them.

One example: A former education volunteer in Madagascar was asked to help bring clean water to the school. A well wouldn’t work because the water table was too deep, and a previous attempt at bringing water from a nearby river through channels wasn’t sufficient. This volunteer was able to connect with a local nonprofit that promotes rainwater catchment systems and helped coordinate the installation of one at her school. Now, students have access to drinking water and can wash their hands after using the toilet.

I’m not sure if Peace Corps will ever change the world, or even Madagascar, in any significant measure. Many of the volunteers like myself question whether we have the skills to help our communities make meaningful changes.

My bedroom in my community boasts a Peace Corps-issued mountain bike, a giant 1996 map of the world from the old Edward Little High School and my Sun Journal paper tube. Vanessa Paolella photo

When I doubt the impact of our work, I think about the convictions of the Peace Corps staff here, nearly all of whom are Malagasy. We may not see the long-term impacts in our communities, but they assure us that they do.

Over the years, many communities across the country benefit from hosting bright, eager volunteers, they tell us. Sometimes the change is small, like the woman who became more financially secure after starting a business making hot pepper sauce with the help of a volunteer.

Other times, it’s far-reaching; In the dining hall of the training center one night, a staff member told me he was shocked at the level of English proficiency he found in a village that had hosted education volunteers for 10 years. English fluency here, as in many other countries, means better job prospects and educational opportunities.

I don’t know what, if anything, will come from my two years here. Any changes that come from our efforts will likely be small and easily overlooked. But I’m excited for the challenge.

Vanessa,

I wish you well in this challenging project. Hopefully it is one you will find personally rewarding, and hopefully a small group of people you interact with on a day to day basis will find your efforts rewarding.

Know that it is raining hard in midcoast Maine today, with high winds.

Cheerily,

Charlie Ipcar (Ethiopia 1965-68)

Richmond, ME