Paul Theroux on mass travel, British B&Bs and why flying is like ‘being at the dentist’

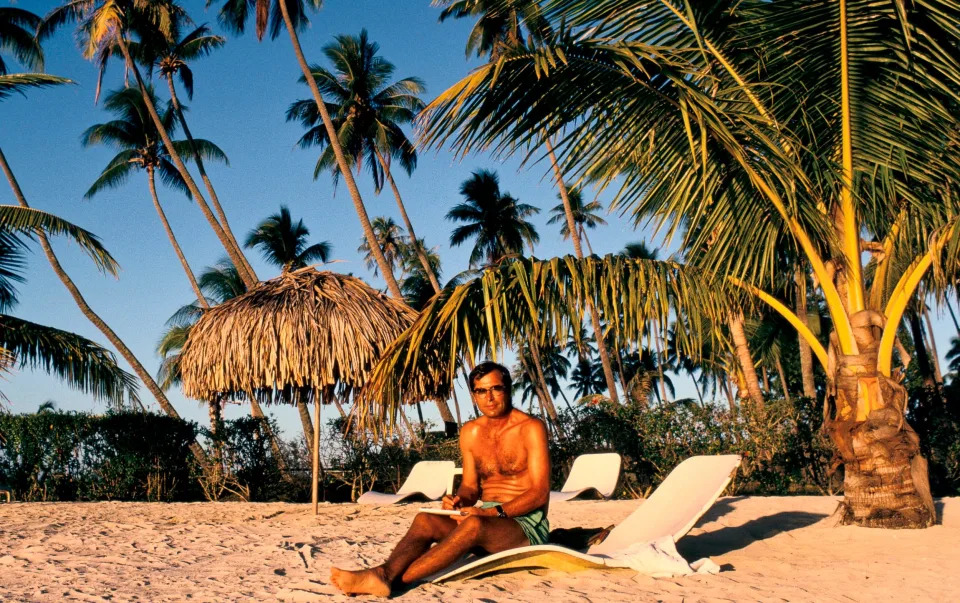

Paul Theroux on a beach in Tahiti, French Polynesia, 1991 – Getty

The democratisation of world travel has its downsides. Paul Theroux, that most celebrated of postwar travel writers, is often collared by readers who have read his landmark works – The Great Railway Bazaar, which recounts Theroux’s 1972 journey by rail from Great Britain to Japan, for example; or Riding the Iron Rooster, on his clattering passage through 1980s China to Tibet – and found his accounts at odds with their own experience of, say, a resort-littered Kenyan coastline, or a modern-day Singapore awash with super-malls and 7-Elevens.

“Readers will say to me, ‘Well, you know, I went there and it wasn’t like that’,” Theroux tells me from his home in Hawaii, where I’ve interrupted the venerable writer feeding his gaggle of pet geese.

“What they forget,” he continues, “is that these books are historical artefacts. In the case of The Old Patagonian Express, I wrote it several decades ago, when I was a quite different person: a younger man and healthier, I suppose, but also homesick and missing his small children.” (At the time of writing The Old Patagonian Express, Theroux’s sons Marcel and documentary filmmaker Louis were aged 10 and eight respectively, and at home in south London with Theroux’s British first wife, Anne Castle.)

Paul Theroux’s seminal book The Old Patagonian Express is being released as a collectors’ edition – Alamy

For Theroux, the ephemerality of travel books is their charm. “They are a snapshot of a place and moment of time that, for good or bad, is unrepeatable,” he tells me. “The food, the landscape; the good or bad governance.”

Aged 81, Theroux has a multitude of countries under his belt and nearly 50 long-form works of travel writing and fiction, including his 1981 novel The Mosquito Coast, which became the 1986 film starring Harrison Ford and Helen Mirren.

Today, I’ve caught Theroux in reflective mood as he looks back on his literary legacy and the momentous changes the world and its natural landscapes have seen since he left the USA as a 22-year-old Peace Corps volunteer, armed with a bachelor’s degree in English, a notebook and pipe. “Back then, places like Singapore [where Theroux was based for three years from 1968 to 1971] looked much as they had in the 19th century, with their old wooden shop fronts. Travel was such a lot of trouble back then, too, and the world seemed gigantic.”

Paul Theroux at Central Station

On March 14, The Old Patagonian Express was rereleased with a new foreword and archive photographs. First published in 1979, it’s one of the author’s best-regarded travel books and recounts his journey along the length of North and South America, beginning at his childhood home in Medford, north of Boston, where he boarded the city’s subway on a frigid winter’s day.

Over two months, a series of increasingly dilapidated trains transport Theroux south through the grey oatmeal landscapes of Oklahoma, the sprawling jungles of Guatemala and the lush Inca terraces of Peru, towards Theroux’s last leg and the book’s titular conveyance, the Old Patagonian Express, a narrow-gauge steam train that’s a “demented samovar” of bumping couplings, belching black smoke and leaking pipes that heralds the beautiful hills and dales of Patagonia.

Whether trembling and windowless (as in Guatemala) or, as on the Lone Star Amtrak train from Chicago to Oklahoma, a smooth ride refreshed by the dining car’s halibut and chilled Chablis, rail is Theroux’s companion in The Old Patagonian Express: comforting and intransigent by turns. Then as now, he loves a train, however rasping and half-sprung.

Theroux bitterly regrets the necessity of two short-hop flights from Panama to Barranquilla in Colombia, and from Guayaquil in Ecuador to Lima in Peru, sentencing him to the “deafening drone and chilly airlessness” of a plane, an experience he likens to “being at the dentist’s; even the chairs are like dentist’s chairs.’’ Does he welcome the proposed new “golden age” of rail that’s seeing new sleeper and high-speed rail routes spider across Europe and North America?

Theroux’s journey took him through the beautiful hills and dales of Patagonia – Alamy

“The story of rail is odd, in a way, in that it’s both coming and going,” Theroux replies. “I went on every train in China in 1986 and 1987 [for Riding the Iron Rooster] and all of those trains have now been modernised and become high-speed trains; much as the Chinese have greatly improved train services in Kenya and Angola. Sadly, in other countries, including most of those I travelled through for The Old Patagonian Express, rail travel has been more or less eliminated, because it is expensive to run. These days, Mexico is connected quite admirably by a fleet of so-called ‘luxury coaches’.”

Theroux pauses for a moment: “But, you know, I do love travelling by train. The idea that you can get on a train in London and go to Paris, or you can get on a train in London and go to Hong Kong, for that matter, if you have a lot of time on your hands, it’s really quite wonderful.”

Theroux lived in the UK for 17 years, settling in Battersea with Anne, whom he met in Kampala where she was teaching at a girls’ secondary school. His years here gave rise to The Kingdom by the Sea, Theroux’s account of travelling the coast of the British Isles from Dover to Cornwall, Ulster to Scotland, by public transport. The trip that informs the book took place in 1982 at the height of the Falklands War and Theroux finds Britons in an unusually garrulous mood.

Theroux in 1989 at the age of 48 giving a talk in Hawaii, which he now calls home – Alamy

In Deal, Theroux stays at a greying B&B run by (as he rechristens her in Dickensian vein) a penny-pinching Mrs Sneath, whose television room is full of drifters weighing in on the likelihood of the “Argies” gobbling up the Falklands’ resident sheep; in Ventnor, he meets the Doggets and Thackwoods, tourist couples who bond over the incompetencies of local councils and “settle down to a long pleasant afternoon of complaining”.

Theroux’s Britain is by turns secretive, rose-growing, window-washing, dog-loving and quaintly beautiful. With Visit Britain forecasting a bumper year for inbound tourism from the US to the UK in 2023, what does he say, these days, to fellow American tourists bound for our green and dyspeptic land?

“Britain is a wonderful place to visit and some of my happiest memories are there,” Theroux says. “I wrote The Mosquito Coast sitting in a house in Wandsworth that I bought for £32,000 in 1975, can you imagine?”

He is then rendered momentarily speechless when I tell him that the going rate for a cheap B&B in the UK, £5 in his day, now nudges £100 a night.

“Well, I always say get out of London and travel by rail if you can.” Theroux disapproves of his fellow nationals’ tendency to seek out Dickens’s London of fog and stovepipe hats, or Henry James’s coastal cottages and curates. “You can go and sit in Fleet Street and imagine that you’re Samuel Johnson,” he says, “but it’s a pointless quest. One has to arrive in a place and see it as it is.”

The Old Patagonian Express is set to be released as a collectors’ edition

The steady march of global tourism is a challenge for writers who follow in the shoes of Theroux and his generation, who travelled when the world seemed untrammelled and the concept of being an “adventurer” wasn’t quaint.

Modern travel writing – whether it’s the spiritual musings on nature of the author Jini Reddy or the thoughtful ruminations on Indian rail of writer Monisha Rajesh – is less about those bravura encounters with rutted roads and clapped-out rail, and more diverse and intimate in its focus. These days, it’s hard to imagine a pining young father getting through 429 pages of prose, as Theroux does in The Old Patagonian Express, with barely a reference to his wife and children back home.

Theroux concludes that he has no truck with travellers who avoid spots sniffily dismissed as “too touristy”. “You go to [major resorts such as] the Costa del Sol and the way of life is totally different if you venture just a few miles inland,” he argues. It’s also to his countrymen’s discredit that so many Americans have visited Bangkok and London, but not the US South, where, as Theroux records in his 2015 travel book Deep South, entire villages remain as they were in the 19th century, “very friendly but poor and with few or no banks or shops”.

It’s surprises such as these that keep Theroux going and keep him planning new trips, most recently as a guest lecturer on Silversea Cruises’ Southeast Asia itinerary to Sri Lanka, Thailand and Malaysia. “The important thing is not to be lazy or cynical about seeing the world,” he says. “Just leave your home, get out there and travel.” And with that, Theroux is off into the bright light of the Hawaiian morning to feed his clucking geese.

The Folio Society edition of Paul Theroux’s ‘The Old Patagonian Express’ is available exclusively from foliosociety.com, at £65.

John,

I greatly appreciated this informative romp through Paul Theroux’s contemplative thoughts on global travel. Good for you!

What a terrific piece on my favorite living American writer! Thank you!

Reading Theroux’s works over the years has been such a treasure. Sometimes he’s writing about an exotic place where I have also visited, but he always brings a new image of it into my mind. And the places where I haven’t bee — well, he does it for me.

It’s now nearly 2a.m. In Philippines and I thought I’d check my email and saw this gem and dived right in. Always a delight to read Paul and to read of Paul. I packed in his Ghost Train to the Eastern Star and am mesmerized. Back to Yokohama and reality tomorrow on graveyard flight. Thanks for sharing, John.

What lifelong unquenchable curiosity of other cultures and places and adventure

– and the discipline and desire to manifest it all in his vivid writing – to share with the world.

I want to get on a steamship tonight to anywhere and everywhere 🙂

Thank you, Paul – and John for sharing.