Part Six–First RPCV Ambassador: Parker Borg

Parker Borg was a PCV with the initial group of Volunteers to the Philippines, 1961-63. While not from Yale, but Dartmouth, Class of ’61, Parker was nevertheless “pale and male.” What made him rare in the State Department was that he was an RPCV. He would be nominated by three separate Presidents for Ambassadorial positions: Mali, Burma, and Iceland, but never went to Burma because of Senate objection to Burma’s human rights problems. When first nominated to go to Mali in 1981, the Peace Corps Director, Loret Ruppe, was thrilled by the news. Finally, the State Department would have an RPCV Ambassador. It had taken the State Department twenty years to fulfill JFK’s hope for the Peace Corps, that someday RPCVs would fill the ranks of U.S. Ambassadors.

(We all know how slow the government bureaucracy is. Peter McPherson (Peru 1965-66) was named the Director of AID also in 1981, making him the first former volunteer to head a federal agency.)

In a 2002 interview with Charles Stuart Kennedy for the State Department’s Oral History project Borg explained how he joined the Peace Corps. Coming from a middle class Republican family in Minneapolis, Minnesota, he hadn’t voted for Kennedy, but was intrigued by the idea of working overseas in a new US program as a volunteer. “It sounded like a fantastic idea. I went down to Washington from Dartmouth at spring break to the Peace Corps office and told them I wanted to join. My family was appalled I would be considering something like this after graduating. They didn’t think much of any government programs; the world of business was what mattered to them.”

Parker explained to the recruiting office, his focus on international relations in college, his enthusiasm about the new program, and his interest in possibly becoming a teacher. The official at the Peace Corps office didn’t think much of his qualifications.

“We don’t want people from Ivy League colleges,” they told him in Washington. “We want people who’ve gone to ag schools and technical schools and who can do the sorts of things we need to do.”

Declared persona non grata for having gone to an Ivy League school and having earned a liberal arts degree didn’t discourage Borg. He immediately found out where the first Peace Corps programs were going and the required skills.

“There were programs for Tanzania, Ghana, Santa Lucia and the Philippines,” he recalled. “They were all technical except the one in the Philippines. The Philippines was going to be an education program. So when I filled out my Peace Corps application, I said I wanted to be a teacher. To my surprise, I was selected despite my lack of teaching background but, I guess, because I had indicated an interest.”

Assigned to a school in a small town in the province of Camarines Norte on the island of Luzon, he worked as a teacher’s aide in an elementary school, the only volunteer at the school. “I taught beginning English to first graders; I taught mathematics skills to third graders; I taught science to some sixth graders; I expanded into the local high school where I also taught literature to eighth graders; current events and history to some seniors. It was great fun. I had a wonderful time.” Borg felt he had to work extra hard to prove to himself and to those who doubted his qualifications that, despite the absence of a proper background the Peace Corps official had told him they wanted, he could do the job.

He also came to realize something else as a PCV. He observed a bit about how our State Department operates and what our diplomats did overseas.

“As a volunteer, I was required to find a project for the months when school was not in session. Most of my colleagues worked with local youth in summer camps, but I wanted to learn more about US Government operations overseas. In the summer of my second year, I went to the Director of the USAID Mission, and asked about working for free in the office. This experience gave me my first opportunity to see American Foreign Service Officers and I was appalled.”

As somebody who felt a connection with rural life in the Philippines, Parker didn’t think the Foreign Service officers he met had much connection with the country. “They were mostly younger guys doing visa work and participating in what I thought was the most frivolous sort of life, traveling relatively little outside of the capital, going out on their sailboats on the weekends, living an American life in this foreign country.”

“In many ways this is, of course, the typical reaction of PCVs towards embassies. We’re out in the boondocks and we’re living the ‘real’ life; the diplomats are up in the capital and don’t know the country. I think this is duplicated almost everywhere in the third world.”

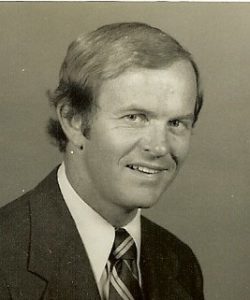

Future RPCV Ambassadors Brenda (Brown) Schoonover & Parker Borg and other PCVs in Philippines, 1961.

While less than certain about following a diplomatic career, Parker took advantage of a Peace Corps offer of a free trip to Manila to take the Foreign Service Exam. (What PCV won’t take advantage of a free trip to the capital?). Although he passed the written and oral exams, he put off joining the State Department until he had finished two years of graduate school and could reflect further about a post Peace Corps career.

In his State Department orientation class, he was not impressed by some of the new diplomats he was meeting. He, Leo Cecchini (Ethiopia 1962-64) and Weldon Burson (Colombia) were the only RPCVs in the group.

“They were overwhelmingly white and male. There were no minorities. There were only three females. I found some of the people interesting, but talking to a few of my new colleagues, they said that being selected for the Foreign Service was the greatest thing that would ever happen in their lives. It struck me they had rather limited perspectives on what it was that they were entering.”

Parker’s first assignment with the State Department was to Malaysia, where he found some of his best friends among the local Peace Corps volunteers. They were closer to him in age and their orientation to local events.

After assignments in Vietnam and several jobs in Washington, Parker got another overseas job, this time as head of the US Consulate in Lubumbashi, Zaire (now the Congo). During his two years in Zaire, he made a point of getting to know all the members of the Peace Corps community in his consular district. This became extremely useful when insurrections (known as the Shaban Wars) evolved two years in a row, first in 1977 and then in 1978, which required the quiet extraction of many volunteers from their communities without getting them too excited or notifying government officials that this was an evacuation.

Later as Director of West African Affairs at the State Department in Washington between 1979 and 1981, he traveled frequently in West Africa, generally including visits with PC offices and volunteers in the field in addition to the formal visits with the Embassy and AID mission.

In Mali, when he became the Ambassador in 1981, Parker found a Peace Corps program of about 50-60 volunteers scattered widely throughout the country, but generally within a two-day drive from the capital. At first the Government of Mali, then more closely allied with the Soviet Union than the West, attempted to curtail his travel out of the capital, demanding two-week advance notification and an official government escort. When he explained later that he wanted to visit Peace Corps volunteers, the door to travel opened up and he met with many volunteers over the next three years.

When volunteers learned that the Ambassador had been a volunteer himself 20 years earlier, they wanted to know about conditions, expecting that being a PCV back then was much more difficult than it was for them. Looking at their housing, daily jobs, and solitary lives, Parker had to admit that the volunteers in Mali had much more challenging lives than anything he faced many years earlier.

He recalled in his oral history that the number of volunteers grew while he was there, as did the number of extensions after their two year tours expired. There was something like a 60 percent request to stay on for a third year. To his mind that signaled a good program. Volunteers were involved in small-scale agricultural production, health care and community development; all rural projects, focused on basic human needs. Furthermore, he felt that per dollar spent, the American taxpayer got a better return out of our Peace Corps investment than we did out of the AID investment.

“To accomplish the small-scale project was probably much more effective. This was something I had sensed first as a PCV. I saw this over and over again with AID. We would try to do things that were too big, that we couldn’t manage, and that were not appropriate. We tried to universalize some program or some idea that just didn’t take.

“We had something like 30 Americans in our AID office. There wasn’t a single one who spoke French well enough that they could participate in meetings where we were trying to adjust the economic policies of the country and make the agricultural sector more productive. So I attended a lot of these meetings myself, and then I found a Belgian who was a World Bank employee whose wife was working in the country, and I got the AID mission to hire him. So we had a Belgian as our principal liaison working on food security because there was nobody in the mission who had the capability in French or who had the portfolio that would let them go out and look at whatever the small project of the day was.”

While early Volunteers, though from the 60s and 70s, had the reputation of being against the government, Borg did not see any difference between his generation of Volunteers and those that came later into the agency. “I felt that the idealism on the part of the volunteers wasn’t much different from the idealism that I had experienced when I first joined the Peace Corps. I never felt any particular hostility from the Peace Corps towards myself or to other people in the embassy, but I’m not sure if part of that wasn’t because we went out of our way to talk with the Peace Corps volunteers when they first arrived, visited them when they were in their communities and tried to help them solve problems within their communities.”

As they say, once a Marine, always a Marine. Well, once a Peace Corps Volunteer, always a PCV.

No comments yet.

Add your comment