“Order and Progress: A Brazilian Peace Corps Saga” by Jack Epstein and Chuck Fortin

Thanks for the ‘heads up” from Leita Kaldi (Senegal 1993-96)

Our RPCVGulf Coast Florida zoomed an extraordinary presentation last Saturday with the two authors of a “Brazilian Peace Corps Saga.” I believe it would be of interest to PCW readers. Here are the authors’ bios and an abstract. It’s not in book form, but is an article that will be published in Brazil. — Leita Kaldi

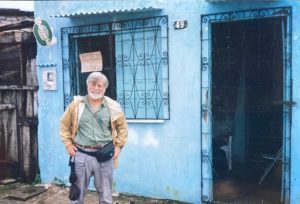

Jack (left) and Chuck in 2016

Jack Epstein (Brazil 1968-70) received a BA in Latin American Studies from UCLA. He is the foreign wire editor for the San Francisco Chronicle. He previously headed the newspaper’s foreign service department, overseeing coverage by freelancers and stringers from Europe, Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Latin America. In 1993, he moved to Rio de Janeiro where he worked until 1999 primarily for the Associated Press and TIME magazine.

Charles Fortin (Brazil 1968-70) earned his doctoral degree through the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) at the University of Sussex in the United Kingdom. He completed his MSc in urban and regional planning at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, after graduation from the University of Notre Dame. Having taught for 18 years at the Federal University of Pernambuco in Recife, he joined the Inter-American Development Bank as an evaluation officer assessing the environmental impacts of IDB programs and projects.

•

Order and Progress: A Brazilian Peace Corps Saga

By Jack Epstein and Chuck Fortin

Abstract: As Peace Corps volunteers, Jack Epstein and Chuck Fortin arrived in Bahia, Brazil just four months before the military government enacted harsh repressive measures of the Institutional Act No. 5 in December 1968. In their respective favelas, they operated under the vigilant eye of local police authorities who squashed community organizing initiatives and even issued an all-points-bulletin for Jack’s arrest. After vacationing through the Amazon oblivious to police pursuit, they returned to Salvador and Jack was immediately hustled out of the country for fear of arrest, imprisonment, or worse. This saga tells of his exile, of conflicts and tense negotiations with Peace Corps authorities, and his forbidden undercover crossing of the Brazilian border in time for Chuck’s wedding. The story describes the challenges and modest outcomes of community development under military rule. Later, under more favorable circumstances, they both returned to Brazil and, for several years, continued to make their presence felt.

IN THE SUMMER OF 1968, Fidel Castro was nearing his 10th year as leader of a revolutionary socialist government that had overthrown a U.S.-backed dictator, nationalized U.S. oil refineries, and closed casinos run by American gangsters. Successive U.S. administrations feared that a “domino effect” would lead to copycats in our backyard. Under John F. Kennedy, the Alliance for Progress and Peace Corps were established in 1961 to channel aid to the region and provide alternate models for restive populations.

In the 1960s, the cold war struggle to contain communism was the dominant foreign policy goal of the U.S. government. All this helps explain why the two of us found ourselves that summer in a poor, northern region of Brazil, where a right-wing U.S.-backed military junta and the Johnson administration shared the worry that millions of impoverished peasants might push the nation toward open rebellion.

In many ways, we couldn’t have been more different.

Chuck was an Irish-Catholic mid-westerner, a former seminarian who grew up in Whiting, Indiana, and attended Notre Dame University. Before the Peace Corps, his version of an adventure was a trip to visit relatives in “faraway” Cleveland.

Jack was a West coaster of Jewish-Russian origin whose father immigrated to the United States from Latvia, and whose mother was a concert violinist. He attended UCLA and had worked on a kibbutz in Israel.

Before we were assigned to our host communities in the state of Bahia, we had spent six weeks in Brattleboro, Vermont, in Peace Corps training learning Portuguese and grassroots organizing in community development programs designed by Frank Mankiewicz. He later served as press secretary for Sen. Robert Kennedy and George McGovern during their presidential campaigns. Mankiewicz had been inspired by the legendary activist Saul Alinsky, who had organized poor people in Chicago, encouraging local leaders to “rub raw the sores of discontent.” Alinsky also inspired former President Barack Obama, who himself was a community organizer in Chicago in the 1980s.

We both felt it was a unique and astonishing time when the U.S. government-sponsored such programs. But that began to change after President Richard Nixon appointed Joseph Blatchford as Peace Corps Director in 1969. Blatchford, a Republican who lost a House seat to a Democrat in Los Angeles in 1968, aimed to chart what he called “new directions” for the Peace Corps by recruiting more craftsmen, farmers and education specialists rather than young liberal arts graduates just out of college like the two of us.

We spent our first six weeks in Brazil continuing our training in the city of Feira de Santana inland from the capital, Salvador. Our trainers were veteran Peace Corps volunteers — a few had even been Freedom Riders challenging segregation in the south. They told us to figure out what our communities’ residents most needed — be it water, sewerage, or some other basic service — and then help them achieve those goals themselves.

There was just one key hitch: despite its strong alliance with the U.S. government, Brazil’s military government was no fan of the Alinsky/Mankewicz model of organizing poor people to pressure officials for basic needs. As the late Roman Catholic Archbishop of Recife Dom Helder Câmara said at that time: “When I give food to the poor, they (military) call me a saint. When I ask why they are poor, they call me a communist.”

We were given a choice to pick out a town and a poor community known as favelas. We both decided to live where help to achieve basic necessities was most needed. It was a shocking existence for both of us – middle-class Americans who had always lived with running water, electricity, and indoor plumbing, which were lacking in both of our communities.

Santo Amaro da Purificação City Hall

Chuck

Chuck chose Santo Amaro da Purificação, a city of 58,000, and hometown of popular samba superstars, Caetano Veloso and Maria Bethânia.

He picked the town’s poorest neighborhood — Maricá, where shacks bore five-foot-high watermarks created by previous floods that had engulfed the community. Ninety-five percent of dwellings had no running water, electricity, or indoor toilets. With virtually no street lights, hard-working residents typically retired by 8:00 p.m.

Maricá was surrounded on three sides by tidal marshlands where the Subaé River — polluted by a French-owned lead factory upstream — emptied into Bahia’s principal bay, The Bay of All Saints. Chuck’s primitive three-room rental shack, which he helped build, was surrounded by marshland, mangroves, and subject to the tidal ebbs and flows of a tributary that nearly reached his back wall. Mosquitoes, rats, and snakes were ubiquitous. Residents threw garbage and human excrement in backyards or muddy streets amid chickens, pigs, and barefoot children.

Chuck (on roof) building his mud-stick shack in Santo Amaro

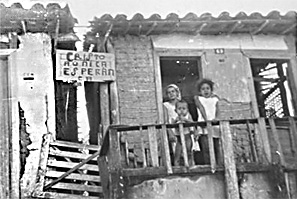

The view outside Chuck’s shack in Maricá favela in 1968.

Two kids swimming in the polluted Subaé River

Jack

Jack opted to live in Valença, a town he had liked for its colonial architecture and picturesque waterfront along the River Una. At that time, it had some 16,000 inhabitants.

Jack’s favela, Bolivia, was populated by squatters most of whom were fishermen who had built shacks atop a swamp. As in Maricá, there was no running water, electricity or paved streets. The water table was also too high to dig privies. Jack’s rented house was by far the nicest on the block — its walls were constructed with cement and mud stick and was a steal at $6 a month.

Both

In both Santo Amaro and Valença, tuberculosis, malnutrition, and intestinal diseases were common as well as such serious tropical maladies as chagas — a disease caused by the bite of the “kissing bug” that affects the heart — and schistosomiasis, caused by freshwater parasitic worms that attack the liver and other organs. We avoided those maladies by investing in mosquito nets to keep out the barbeiro (kissing bug) and staying clear of stagnant water to avoid the deadly worms.

As the only resident American, Jack never lacked for company

Most of Valença’s poor lived in shacks like this The sign says: “Christ announces hope.”

Both of us helped form neighborhood associations to pressure town politicians to provide running water, electricity, sanitation as well as basic health care.

Chuck

In Santo Amaro, Chuck began by showing local children cartoon movies teaching them hygiene practices like washing hands and filtering drinking water. He also organized dance parties, or festas, to earn money for association projects. The parties featured a local band led by a man named Eugênio, a carpenter and saxophone player who became the unofficial association president.

Jack

In Valença, Jack helped form the Associacão de Moradores — a residents’ association — which started sewing classes with donated sewing machines and literacy classes, filled streets with coconut shells that soaked up the mud and chopped down trees for electricity poles after the cash-strapped mayor vowed to supply electricity if the community provided the posts (Alas, he never did).

Members of the Bolivia association cutting down trees to show Valença’s mayor that they were serious about sharing the cost of electrifying their community.

But these seemingly innocuous programs did not sit well with local authorities, and especially with Santo Amaro’s police chief and Valença’s mayor.

The Santo Amaro police raided and searched association headquarters, harassed and interrogated Eugênio, while hurling accusations that the organization was merely a cover for drug trafficking, pornographic films, and prostitution.

Chuck

The police chief then warned Chuck that he was monitoring his movements — even on visits to the state capital of Salvador 50 miles away. He told him that he had no issue with such programs as adult literacy, health education, road improvements, and support for the area soccer team. But organizing residents into a neighborhood association to pressure authorities would be a different matter entirely.

In Valença, similar complaints by the mayor and several high-profile businessmen led to Brazil’s Orwellian-named Department for Political and Social Order (DOPS) – the secret police akin to the Gestapo or Stasi — to break into Jack’s shack while he was out of town. They detected evidence of what they deemed unacceptable political behavior displayed prominently and called for his immediate arrest.

Jack

During the military dictatorship (1964 to 1985), DOPS agents searched for “subversivos, and provided “ideological clearance certificates” for employees in certain jobs. They deemed Jack a “subversivo.”

Fliers circulated in Valença asking “all patriotic citizens” to remain on the telephone if they heard subversive chatter when party lines crossed — common in those days — and to report anything they heard to the authorities. DOPS agents even turned their attention to “subversive music.” Paulinho, who ran Valença’s only record store, once asked Jack to shut the door behind him since he wanted to listen to a song by singer Juca Chaves called “Caixinha, Obrigado,” (“Little box, thank you”), whose lyrics satirized the military (Chaves was later forced to flee to Italy).

Both

Each Bahian town also had a local army garrison whose commanding officer was in charge of ferreting out subversives. In Valença, it was a stocky man called Sgt. Jehovah with whom Jack had a minor run-in at the town’s first-ever art fair after challenging his decision to close it down. Organized by a university student named Nilo from the state capital, it included a painting of Che Guevara as Saint George beheading the U.S. dragon. That was enough for Jehovah to deem it “subversive” and arrest Nilo, who was later expelled from his university over the incident.

Such harsh repression was made possible four months after our arrival in Brazil, when the military in December 1968 declared AI-5 (Institutional Act No. 5), which closed down Congress and gave the government the power to intervene in state and local affairs under the pretext of national security. It also imposed censorship, declared the illegality of political meetings, the suspension of habeas corpus, and the removal of political rights of citizens perceived as subversive.

During its 21-year-rule, successive military strongmen arrested and tortured tens of thousands of Brazilians and executed or disappeared more than 400.

Half-way through our two-year Peace Corps stint, we were both ready for a break and entitled to an allotted one-month vacation. We left not knowing that authorities had issued an all-points-bulletin for Jack’s arrest. The government told the Peace Corps that Jack would be imprisoned if it didn’t send him back to the United States.

Without knowing anything about the mounting problem, and leaving no itinerary, we traveled by bus through the northeastern states of Sergipe, Alagoas, Pernambuco, and Ceara before reaching Belem, the gateway to the Amazon River, where we boarded a steamship to Manaus, the Amazon’s largest city.

We were on the run without realizing it, covering some 5,147 miles. Since our departure from Salvador, we had lodged in cheap hotels in red-light districts, foraged on street food, and merged with poor folks at bus stations and rest stops.

After visiting Manaus, Porto Velho, Brasília, Belo Horizonte, and Ouro Preto, we finally arrived back in Salvador. We were two weeks over our vacation limit and we hoped our bosses wouldn’t notice when we reached the main office, housed in the state lottery building supposedly to prevent a terrorist attack against a U.S. organization. The plan was to check for mail surreptitiously and head back to Santo Amaro and Valença.

Jack

It was there that Jack found an odd message from Peace Corps Bahia Director Romeo Massey. It said: “Jack, Stay in the Office. Don’t Leave. Call me.”

But Deputy Director James LaFleur was in the office with his feet on his desk, reading a Time magazine. Jacked asked him what was up. He agreed to call Massey, who was in Rio de Janeiro. In those days, long-distance telephone communication was so poor that LaFleur had to yell into the phone and say “Over” each time he was ready for Massey to speak.

“Epstein is finally in the office. Over,” LaFleur said. Seconds after that, he hung up.

“We are going to Rio on the next flight,” he told Jack.

“Why?” What’s the problem?”

“I can’t tell you that.”

“OK. Then I am not going.” Jack told him. “I am not getting on a plane without knowing why.”

His reluctance forced LaFleur back for another loud “Over” session with Massey. As Jack eavesdropped, he wondered whether someone had ratted on him for smoking maconha (marijuana) — a serious Peace Corps no-no. He indulged occasionally with a Valença friend, Roberto, who sold seafood.

“Epstein says he won’t go unless he knows why,” La Fleur told Massey. “Over.” He then hung up.

“OK, Jack. I can tell you is this — it’s a political problem. We are going to Rio.”

A political problem? Jack was intrigued. Still not understanding the severity of the situation. He believed it would be nothing he couldn’t talk his way out of. What could he have done that was so serious? And most importantly, he had never been to Rio de Janeiro, a city that he had always wanted to see – and on the Peace Corps’ dime!

LaFleur later said he learned that the U.S. Embassy and the CIA had collaborated with DOPS, giving them background information on Jack – including his family’s “Jewish Russian heritage” and his attendance at anti-Vietnam war protests while a student at UCLA. But apparently, what had started the investigation were complaints from two sources: the U.S. director of the Firestone rubber plantation near Valença — a staunch conservative with whom Jack had some testy arguments over the Vietnam war and the election of Richard Nixon — and the manager of the town textile plant, who had made a special trip to Salvador to denounce Jack as an “advanced socialist” after a friendly exchange of ideas in his office.

It wasn’t until much later that he realized that he had been a VERY naïve 22-year-old American in thinking that as a U.S. citizen he could speak openly in an autocratic society about government repression and not pay a price.

When LaFleur and Jack arrived in Rio, they were met by a U.S. Consulate officer, who took them straight to the Consulate to confer with a Dr. Avery, the Peace Corps country director. Avery showed Jack a list of complaints compiled by DOPS, which included lies and distorted half-truths peppered with an occasional fact. They included:

“He dresses in a bizarre fashion, has long hair, a beard and is considered a hippie.”

”His parents are Russian and still reside there.” (Jack’s mother was born in New York City and had never been to Russia until a vacation in 1982. His father immigrated to the U.S. from Latvia in 1928 at age 14. He became a U.S. citizen and won a Purple Heart fighting Nazis during World War II).

”He gave up comfortable living conditions in the center of Valença to live in a miserable shack in a very poor area.”

”He has made statements on numerous occasions against the military government, president of the republic and admires Cuba, Russia, Eastern Europe and advocates violent terrorism in the model of the Cuban revolution. He has also advocated that all military reservists desert their posts.”

”His shack has pictures of Che Guevara, Fidel Castro, a wooden sculpture of a chained hand and a defaced military recruitment poster in which he has written in Portuguese: You too can become a fascist.” (Jack had a Christmas card with Che’s likeness pinned to his desk sent by a Peace Corps friend in Chile. There were no photos of Fidel Castro, but a photo of Mexican American civil rights leader Cesar Chavez. The chained hand symbolizing slavery in Brazil — Brazil didn’t outlaw slavery until 1888 — was done by a local artist. The doctored recruitment poster was in hindsight – a VERY STUPID thing to display. Jack mistakenly thought that nobody cared what he had on his walls. No one from the “rua” (middle-class residents in town who live on paved streets) ever visited his home — except for his maconha buddy, Roberto, who advised him to take it down. In hindsight, he wished he had listened to him).

”When in Salvador, he visits a Russian-educated Brazilian.” (This referred to a Moscow-educated engineer, who resided at the Pensão Universal, where Jack ate lunch daily. They often talked politics over plates of rice, beans and whatever tasty dishes the owner, Dona Matilde, served. He never saw him outside of Valença.)

“He receives subversive letters from a friend of Mexican origin. This friend lives with Jack’s brother. He is an agitator and participates in demonstrations of a racial nature. This friend has also written about Castroite guerrilla activists and has slandered the Brazilian military.” (This “radical” friend was a fellow UCLA student in the Latin American Studies program, who later became a professor of Mexican American Studies. He was an outspoken advocate for California farmworkers and the civil rights movement headed by Chavez. Jack’s brother, Jerry Epstein, was a violist for 42 years with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra. He had never met Jack’s UCLA colleague and aside from registering with the Democratic Party, had never been involved in politics.)

After reading the DOPS report, Jack told Avery that he had never advocated violence, nor had ever spoken in a public forum against the government, or called for mass desertions from the army. His opinions were made in private conversations with people he never suspected would report him to the authorities. He then asked Dr. Avery to set up a meeting with Brazilian officials so he could straighten out the problem.

“That’s not possible,” Avery told him.

The military had told Avery it’s deportation or jail. Jack would have to sort out his future with Peace Corps officials in Washington. He was then given a plane ticket leaving that night for D.C., $50, and the name of a cheap hotel near Peace Corps headquarters and told to report there as soon as possible. (Avery, by the way, was on the same flight so he could attend an all-Latin American country director meeting later that week).

Jack arrived in D.C. believing the Peace Corps would back him against a repressive dictatorship, especially after pointing out the untruths painted by the secret police. Or at the very least, they would reassign him to another Latin American community development project since he spoke Spanish and wouldn’t need to take another three months training course.

After a week of being grilled by a team of lawyers and the so-called Latin American Selection officer — a shrink — he was told that he would be terminated for breaking the cardinal rule of involvement in a host country’s politics. Nor would they consider re-assigning him for fear he’d go off the rails again.

But Jack refused to take that as the final answer. There was too much at stake. Not only did he really want to continue his work for the Peace Corps, but he knew that if he were dismissed it was likely he’d be drafted and eligible for a war that he had so vehemently opposed.

He then sought the advice of Bernard Lefkowitz, a Peace Corps program evaluator whom he had met a year earlier when he visited Valença to check out the Bahia program. Lefkowitz invited Jack to dine at his home with his wife, Abigail.

Over dinner, Lefkowitz told Jack that the Peace Corps couldn’t fire him until he had passed all his medical exams. He advised him to spread out appointments with an eye doctor, dentist and a specialist in tropical medicine, which would give Jack time to talk to Latin American country directors still in town for their conference, about reassignment. That, he said, was his only chance to remain a volunteer.

“If you can get a country director to accept you, there is not much they can do to kick you out,” Lefkowtiz told him.

Jack wound up spending nearly three weeks in D.C., which gave him time to let Peace Corps lawyers know that he wouldn’t go quietly by bringing up the subject of violation of free speech. He knew that the Peace Corps in 1969 had already been in court over that issue.

Jack’s threat referred to Bruce Murray, who had sued the Peace Corps for wrongful termination. He had been on the music faculty of the University of Concepción in Chile before being recalled in 1967 without being told why. When he arrived in D.C., Peace Corps officials told him that he had been terminated for signing a petition published in a Chilean newspaper that called for the end of the bombing of North Vietnam and immediate negotiations for peace. And on top of that, he instantly became eligible for the military draft in his home state of Rhode Island.

Murray sued for violation of his First Amendment rights and lack of due process and won. The judge handling the case said: “Mr. Murray’s dismissal was “a shocking, unconstitutional act on the part of the Peace Corps.”

(In a March 12, 1970 article, the New York Times disclosed that 12 volunteers had been separated from the Peace Corps because of their public opposition to the Vietnam war.)

Meanwhile, between trips to see doctors, Jack talked to as many Latin American country directors as he could. For all but one of them, his story was enough to send them walking away as if he had a bad case of COVID-19.

Enter John Arango, a former Peace Corps volunteer in Colombia and Panama’s country director. After listening to Jack’s tale for about two minutes, he said: “OK, I’ll take you since you already speak Spanish and we have a community development program. Who do I talk to?”

They then marched into the lawyers’ office to finalize the arrangement. The lead attorney immediately said he would draw up a legal document for Jack to sign that stated he would not return to Brazil while still in the Peace Corps. He refused, telling him that he wasn’t that crazy to return to a country known for torturing and killing dissidents.

Chuck

Back in Santo Amaro, persecution by local police had finally put an end to the association. Chuck then initiated — along with four other volunteer teachers — a two-year adult literacy program at the local school that filled four classrooms with 100 adults nightly. The program earned Chuck the title of “professor,” which mollified the chief of police. There was also high demand and full attendance for such classes. In 1969, the literacy rate in Brazil was about 68%.

Yet Chuck felt he had become complicit with the status quo. The military coup had ended Brazilian educator Paulo Freire’s unique and successful “social awareness” method of literacy training that employed no textbooks but which the military regime perceived as Marxist propaganda.

In its place, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) funded a private initiative by the Evangelical Confederation of Brazil. This conservative aid organization was not tailored to advance social awareness or the problems of poor communities. Instead, students learned to read and write by rote, repeating words, and prescribed phrases. Chuck believed the program had been designed to squash dissension.

Jack

On Friday, October 10, 1969, Jack flew to Panama City, where Arango picked him up at the Tocumen International Airport, and took him to a hotel. Then, on his first full day in country, he was stopped by an undercover agent of Panama’s equivalent of DOPS — DENI.

October 11 happened to be the one-year anniversary of the military coup that brought Gen. Omar Torrijos to power. Jack had been taking photos of the Guardia Nacional general speaking to a large crowd about the glory of his revolution. After examining his instamatic camera and learning that he was a Peace Corps volunteer, the agent told him to move on.

At that moment, Jack swore that he would keep his political opinions to himself in yet another country with a military dictatorship even though many Panameños themselves talked openly about the Guardia’s involvement in prostitution, illegal lottery, casinos, arms and drugs. Torrijos once described the infamous Manuel Antonio Noriega as “my gangster,” when he headed the Guardia’s intelligence unit.

After a week, Jack decided to forego the community development program in Panama City, rationalizing that he couldn’t get in much trouble working in the rural province of Veraguas. The work there involved advising cooperative stores in poor communities that sold consumer goods as well as local farmers’ agricultural products such as fertilizers, seeds and chickens.

He was sent to Santa Fé, a mountainous, isolated village some 185 miles west of the Panama Canal to train for one month with a Peace Corps couple and a Colombian Roman Catholic priest named Hector Gallego. Like Archbishop Dom Helder Câmara, Padre Hector was part of a religious movement called Liberation Theology, which linked religious faith with aiding the poor and oppressed by working for social change.

But the cooperatives were controversial in Santa Fé. The stores cut into profits of local political and economic bosses – so-called caciques – who sold their goods at high prices and paid paltry sums for the peasants’ produce. As a result, many area farmers were forced to leave home several months a year to work on sugar plantations to make ends meet.

In 1968, to try and break the caciques’ economic grip, Gallego organized the Cooperativa Esperanza de los Campesinos (Hope of the Peasants Cooperative) that bought and sold items at fair prices and loaned money at reasonable rates. He paid for this venture with his life.

In 1971, thugs burned down his straw-roofed hut. He barely escaped unharmed. A month later, he disappeared after being taken away by two men who identified themselves as members of the Guardia Nacional. He was never seen again. In 1988, investigative reporter Seymour Hersh wrote in the New York Times that Gallego had been thrown to his death from a helicopter and that U.S. Army intelligence had intercepted a message that overheard Noriega joking that he “learned an important lesson: Always kill a man before throwing him out of a helicopter.”)

Jack

After training in Santa Fé, the Peace Corps sent Jack to Las Palmas, a small Veraguas farming community with dirt streets and electricity by generator between 6 p.m. and 9 p.m. The village was surrounded by communities of indigenous peoples called Guaymi, who were around when Christopher Columbus made a contract in northwestern Panama. The “airport” for the weekly mail plane was a nearby pasture.

During his free time, he visited the closest Peace Corps volunteer, Doug O’Brien, who lived in a tiny community off the Pan American highway called El Piro. Doug was finishing his two-year stint and wanted to see South America before returning to marry his Panamanian girlfriend, Maritza. Jack agreed to go with him.

When they reached Montevideo, Uruguay, they were stopped several times by police searching ID papers. They had arrived in early August 1970, which coincided with the dramatic search for an abducted American police adviser named Dan Mitrione. Police and soldiers seemed to be everywhere.

Mitrione had been kidnapped by the leftist guerrilla group, Tupamaros, whose members said he had taught local police torture methods to extract information. They threatened to execute him if the government didn’t release 150 political prisoners. The government said no to their demands and Mitrione was later found in a car shot to death. (Movie director Costa-Gavras told the story in “State of Siege,” a 1972 French film starring Yves Montand as Mitrione).

Doug and Jack agreed that it was time to leave Uruguay, but for where?

João Batista Neto Chamadoura, a Brazilian schoolteacher they had met in Peru, said they could stay at his apartment in São Paulo. Doug — anxious to see Brazil — accepted the invitation. That forced Jack to think about his pledge to the Peace Corps lawyers. He rationalized that the risk would be minimal since they would be crossing into Brazil over a land border without the vigilance of an airport. And if he stayed just a week in a city of more than 10 million people — that would be enough time to eat feijoada, drink a few chopps and caipirinhas and matar saudades (“kill the nostalgia”) as Brazilians say. Then he would return to Panama.

But once in São Paulo, he thought about Chuck, who was about to marry his Bahian fiancée, Sonia, seen here in the doorway of Chuck’s home in Santo Amaro in February 1970. With her Tia Olga, she had come to celebrate the feast of the Lavagem da Purificação.

Chuck’s future wife Sonia inspecting his finished home in 1970

Jack had received a pro forma invitation in Panama and knew the date of the ceremony — August 12 — was just days away in Salvador. When he saw a long-distance bus pass by with Salvador as its destination his thinking — or lack thereof — abruptly changed. It had been a year since his expulsion. Why would the military care if he went to his friend’s wedding? And so far, so good. Nobody had bothered him. He then bought a ticket the next day for the 36-hour, 904-mile slog to Salvador.

Aboard the bus, a small world story ensued.

Jack sat next to a chatty middle-aged woman who told him that she was going to Salvador to attend her niece’s wedding. He told her that he was also going to Salvador to attend a friend’s wedding. She said her niece was marrying an American. He said his American friend was marrying a Bahian. They both stared at each other.

“Charles?” She asked. “Sonia?” he answered.

When they arrived in Salvador on the eve of the wedding, Tia Olga invited him to share a taxi to Sonia’s parents’ home. When they arrived, Olga asked Jack to carry her bags. Chuck answered the door and gave her a huge hug. Then Jack piped up: “Chuckie, where do you want me to put these bags.”

His jaw dropped.

That night Jack attended Chuck’s bachelor party at the swank British Club with many Peace Corps volunteers in attendance, including Massey and LaFleur. Massey told Jack that he would set up a meeting with the American Consul and that Jack must see him as soon as possible.

Years later, LaFleur claims a Brazilian colonel friend of his had informed him that Jack had crossed into Brazil and was heading north.

“I was not surprised when Jack showed up at the party,” LaFleur said recently. “I told him that the military knew where he was and that he was in danger. Jack did not listen and later went to the wedding. I really believe that Jack has a guardian angel or two taking care of him.”

After the wedding at Salvador’s Igreja da Nossa Senhora da Vitória, Jack went to see the U.S. consul, 31-year-old Alexander Watson.

Jack told Watson that he didn’t want any problems with the government but now that they knew he was back in Bahia, he wanted closure by visiting Valença to say goodbye and explain to people why he had abruptly disappeared. Then, he would return to Panama.

Watson didn’t try to talk him out of the visit. Instead, he gave him a letter that said “Jack Epstein is a Peace Corps Volunteer in Panama, who is on vacation and intends to return to Panama. If there are any problems, please contact me.” He then stamped it with the official Consulate seal.

Yes, Jack indeed had guardian angels named Lefkowitz, Arango, and Watson.

With Watson’s letter in hand, Jack returned to Valença and spent several days visiting friends in town and in the favela. Along the main drag, he spotted Sgt. Jehovah giving him the stink-eye. Jack assumed the sergeant was ordered to leave him alone for he did not approach him.

Chuck

Chuck, meanwhile, focused his efforts on four projects: the aforementioned-adult literacy program, a health center, filling in muddy streets with quarry sand, a social club and garnering support for youth soccer teams. The pursuit of those ends featured endless fits and starts, countless City Council sessions, extended periods of discouragement during long intervals when nothing happened along with the nagging notion that nothing would ever come to fruition. American “can do” had grudgingly yielded to Brazilian acquiescence, “se Deus quiser” (“if God wills it”). Chuck then hit upon the idea of opening a medical center stocked with sample medicines from doctors in Santo Amaro and Salvador. He then coaxed the mayor, the local Lions’ Club and the Rotary to pay the rent for the new center.

By 1978, even though Peace Corps had ended its presence in Brazil, Maricá had undergone notable infrastructure changes including paved streets and electrical transmission lines, and other improvements.

Years later, Chuck finally returned for a brief stopover visit to Maricá in 2003. Water contamination has been one of Brazil’s more stubborn challenges, primarily in Rio’s Guanabara Bay, São Paulo’s Tietê River, and Bahia’s All Saints’ Bay. Since 1950, the quality of Bahia’s bay waters has competed with the effluents from an oil refinery, industrial park, petrochemical complex, and the rural sugar cane runoff that spills into smaller rivers, such as the Subaé, that empty into Brazil’s second largest bay.

During his Peace Corps time in Maricá, Chuck had been oblivious to the effects of the French-owned lead factory just two kilometers upstream on the other side of town. It operated on the banks of the river from 1960 to 1993. Lead and cadmium slag extinguished most life in the river except for some crabs that mired in the mud downstream adjacent to his shack.

By 2003, as an evaluation officer with the Inter-American Development Bank, Chuck was responsible for the assessment of Bank-supported projects in water decontamination in these waterways. This evaluation took him once again to Santo Amaro to witness some of the changes that had taken place.

The Subaé was still muddy but finally free of the effluents from the production of 900,000 tons of lead ingots that during operation caused the death of 940 workers and contaminated and crippled a minimum of 18,000 people. The poison and the effects generated by the plant would undergo highly-publicized scrutiny and measures meted out by the Senate’s Human Rights Commission in Brasília.

Jack

Twenty-three years after Jack’s ouster from Brazil, he moved to Rio de Janeiro with his wife, Katherine Ellison, and a Samoyed named Clea, where he worked as a reporter primarily for the Associated Press and TIME magazine. Katherine, who had shared a Pulitzer Prize with two other reporters in 1986 for International reporting on the Philippines, had been named Rio bureau-chief for the Miami Herald after spending five years as bureau chief in Mexico City for the San Jose Mercury News.

It was 1993 — eight years since the end of the military dictatorship — and Brazil was a different world. No more DOPS, or paranoia for speaking out. Former jailed “subversives” like Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff would later become presidents of the republic. The military seemed content to stay in their barracks.

In 1999, Katherine and Jack decided to return to California. But before their departure, Jack told her he couldn’t leave without seeing what had happened to his Valença neighborhood.

He traveled there with Carolyn Kazdin, who had also been a community organizer in Valença and had since become an AFL-CIO activist. They had kept in touch and she wound up spending 11 years in São Paulo as an adviser to a major Brazilian union.

Valença had also changed. With some 60,000 inhabitants in 1999, the town had become the gateway to the gorgeous white sand beaches of Morro de São Paulo island, a short boat ride away. It had also become the largest city on the so-called Dendê (palm oil) Coast and had dozens of inns and hotels to meet the annual demand of tourists in the summer months. (Its population is currently 82,000).

Jack found his house still standing and vastly improved and his next-door neighbor, Dona Naí, in the same home. When she saw him, she smiled, grabbed his face, then told him to wait while she changed into better clothes.

The changes to the neighborhood were stunning. The once muddy street had been paved and, while the neighborhood was still poor, it now had the basic necessities that the association had fought for — lights, running water, and real streets.

When Jack asked the then-Valença mayor, Ramiro Campelo – whom he had known previously as a town councilman and owner of the Pirelli tires franchise — how these changes came about, he answered in one word: “Democracy.”

It turns out the neighborhood is now Valença’s largest voting bloc in a nation where voting is obligatory. If politicians want to stay in power, they must pay attention to the community or risk being voted out of office, Ramiro said.

Jack was also happy to see that homes now had numbers and his street an official name — Avenida Rua Senhor do Bonfim. Dona Naí said that some residents had wanted to call it Rua Joaquim, the Portuguese name that Jack used since folks had trouble pronouncing Jack.

But that didn’t happen. He lost out to the neighborhood cachaça vendor.

•

EPILOGUE

Today, local community organizers are as badly needed in Latin America as they were in the 1960s. The region remains the world’s most unequal in income inequality, undermining its economic potential and the health of its population. About 62 million of its inhabitants live in extreme poverty, which means a lack of access to such basics as food and shelter. The impact of COVID-19 is expected to increase the number of the very poor to 96 million, according to a recent U.N. report.

In Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro, the far-right former Army captain, has broadened the powers of the military and former generals in his administration. His most ardent supporters want a military takeover that would enhance his powers — and Bolsonaro has even attended their rallies.

Chuck Fortin — After the Peace Corps, Chuck returned to the United States and Madison, Wisconsin, to complete his graduate studies in urban planning. In Jacksonville, Florida, he served as planning director for neighborhood improvement in low-income areas.

In 1974, he returned to Brazil, where he taught for nearly 18 years and coordinated the graduate program of urban and regional development at the Federal University of Pernambuco in Recife. During that time, he received a doctorate degree in International Development at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) from the University of Sussex in the United Kingdom.

In 1995, he departed for Washington, D.C to work as an evaluation officer with the Inter-American Development Bank responsible for the assessment of the environmental impacts of Bank-supported programs and projects. In this capacity, he traveled to nearly every Latin American and Caribbean country to evaluate projects, which included living conditions in Santo Amaro. Later, as an independent consultant, he focused on the evaluation of OAS (Organization of American States) anti-drug training programs throughout the region and assessments of natural disaster risk management initiatives in the Caribbean.

He is the author of Rights of Way to Brasília Teimosa, the Politics of Squatter Settlement (Sussex Academic Press, 2015). Today, a member of the Local Planning Agency, he lives in Dunedin, Florida with his wife, Lisa, a former executive of the Baltimore County Public Library System.

He is the author of Rights of Way to Brasília Teimosa, the Politics of Squatter Settlement (Sussex Academic Press, 2015). Today, a member of the Local Planning Agency, he lives in Dunedin, Florida with his wife, Lisa, a former executive of the Baltimore County Public Library System.

Jack Epstein: His travels throughout Latin American became a book: Along the Gringo Trail, A Budget Travel Guide to Latin America (And/Or Press, 1977). By 1980, he had begun a journalism career, free-lancing from Central and South America mainly for the now-defunct Pacific News Service (PNS), a San Francisco alternative wire service.

(And/Or Press, 1977). By 1980, he had begun a journalism career, free-lancing from Central and South America mainly for the now-defunct Pacific News Service (PNS), a San Francisco alternative wire service.

In 1982, he received a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism to research the links between Central America’s Miskito Indians and the CIA, spending four months in Nicaragua, Honduras and Costa Rica, producing a series of articles with another reporter for PNS and the National Catholic Reporter.

In 1989, he moved to Mexico City to teach journalism at the American School and free-lance for numerous newspapers, including the San Francisco Chronicle, Los Angeles Times, Houston Chronicle, Seattle Times, Cleveland Plain Dealer, Christian Science Monitor, Fort Worth Star-Telegram and the Dallas Morning News.

Upon his return to the U.S. in 2000, he joined the San Francisco Chronicle as its Foreign Service Editor. He is still there editing foreign news. He lives in San Anselmo, California with his wife, Kathy, and two dogs.

John Arango: The former Peace Corps official is still fighting the good fight. In the 1980s, he was coordinator of the Haitian Refugee Pro Bono project, which recruited lawyers to help refugees seeking political asylum. In 2017, he resigned from the Sandoval County Planning and Zoning Commission in New Mexico after it approved oil and gas fuel use on unincorporated areas without giving notice to adjoining property owners or giving the public an opportunity for public review.

John Arango: The former Peace Corps official is still fighting the good fight. In the 1980s, he was coordinator of the Haitian Refugee Pro Bono project, which recruited lawyers to help refugees seeking political asylum. In 2017, he resigned from the Sandoval County Planning and Zoning Commission in New Mexico after it approved oil and gas fuel use on unincorporated areas without giving notice to adjoining property owners or giving the public an opportunity for public review.

Bernard Lefkowitz: Before his death from cancer in 2004 at age 66, he worked as an investigative reporter, a true-crime author, an assistant editor at the New York Post, and as a journalism professor at Columbia University.

Bernard Lefkowitz: Before his death from cancer in 2004 at age 66, he worked as an investigative reporter, a true-crime author, an assistant editor at the New York Post, and as a journalism professor at Columbia University.

Alexander Watson: The U.S. Consul in Bahia later became U.S. Ambassador to Peru and was tapped by President Bill Clinton to be U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs. In 2004, he joined Diplomats and Military Commanders for Change, a group of retired diplomats and military commanders who supported John Kerry for president over George W. Bush for the latter’s failure of “preserving national security and providing world leadership.”

Alexander Watson: The U.S. Consul in Bahia later became U.S. Ambassador to Peru and was tapped by President Bill Clinton to be U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs. In 2004, he joined Diplomats and Military Commanders for Change, a group of retired diplomats and military commanders who supported John Kerry for president over George W. Bush for the latter’s failure of “preserving national security and providing world leadership.”

Romeo Massey: In 2007, Massey re-joined the Peace Corps as country director in the Dominican Republic after 13 years at Florida State University, where he served as director of the Center for Information, Training and Evaluation Services. In addition, Massey has held various contracts with the U.S. Agency for International Development and C.A.R.E. in Uganda, Belize, and Honduras. He remained Peace Corps director in the Dominican Republic until 2011.

James LaFleur: For years, LaFleur worked as an economist and as a consultant in Maputo, Mozambique for Booz Allen Hamilton, the accounting and consulting firm, where he is the American liaison for business-sector development projects developed by the United States Agency for International Development for the Mozambique government. He currently lives in Takoma Park, Maryland. His wife, Socorro, once worked as Dom Helder Câmara’s secretary.

Thank you two for your clear assessment of your PC experience.

I was in a Recife community development program, training in Brattleboro from August to November, 1968. Jim LaFleur was our training director, Socorro a language teacher. Max Creighton, Sue Jameison, Pat Kling, Carlos Lundy, the Coxons, the Rockleins, Elbert McAllister all PCVs with me, Michelle St Clare with us in training.

Sometime I’ll share some of my experiences, but I want to thank you for being very honest and self-effacing (in your welcome reference to maconha and to your youthful behavior that could and did get you into trouble). Very refreshing as I sit in my COVID protected house and go back through my life of photography and through my Brasil pics and often go to sleep with memories of fifty years ago. Oh yeah, I went to UCLA (’68), English major. Small world.

https://fototake.smugmug.com/Musing-in-the-Time-of-Virus/Dom-Helder-Camara/

https://fototake.smugmug.com/Musing-in-the-Time-of-Virus/Dom-Helder-Camara/

https://fototake.smugmug.com/Fine-Art-Photography/The-Dozen-Brasil/

Peter, thank you for your kind comments and musings about somewhat uncanny coincidences. Jack and I have put together a companion piece that may appear here one day. If not, you may contact us for a copy: “From Brattleboro to AWOL in the Amazon.”

Chuck…what a life experience you have had! Far from your experiences with a social worker in Indiana. Any memories ? Your name popped up and I found this site. Best to you. Peggy

Hello Jack,

I visited you for a few days in Valença in early 1969 with Bob Chamberlain, who you had studied with at UCLA. We were Fulbrighters in Salvador. We had a great visit, including dancing behind the Trio Elétrico during the pre-carnaval Micareta. Your and Chuck’s experiences and observations are fascinating. It was an exciting time to be in Brazil.

Bob and I finished our PhDs at UCLA. He became a professor of Portuguese at U. of Pittsburgh and I a professor of Spanish and Portuguese at Cal State Fullerton. We’re both now retired.

I’m glad I got to know you briefly 52 years ago, and am pleased that you have been having such a full and adventuresome life.

Um grande abraço,

Ron Harmon

Chuck and Jack, um abraço from Austin, Texas.

Ron Yokubaitis & Carolyn Yokubaitis ( Peace Corp/Brasil 1968-70). Carolyn and I trained with y’all in Brattleboro, VT and were sent to Southern Brasil, Londrina, Paraná three hours North by bus from Paraguay.

Our lives diverged from y’all’s.

The only “straight job” we’ve had that paid us monthly was Peace Corps. Those two years were memorable working in Favelas in Brasil.

Upon our return started working for ourselves and have ever since. When we went to the 40th reunion in Bethesda, MD, all were asked to stand up and tell how they made a living since Peace Corps? About 40 RPCVs stood up to inform us all. Everyone had worked for some level of Government from City/County to Foreign Service. Carolyn and I were the only ones who had worked for themselves all that time. Freaks.

After several humble businesses in Texas and birthing five boys, four @home, we started the first Internet Service Provider in San Antonio, Texas, in 1994, Texas.Net.

As Carolyn says: “ we got early on the Internet that we got the name TEXAS !”

We grew our Usenet Newsgroups company, GigaNews.com globally with equipment and customer both retail and wholesale in over 20 countries.

Jack will like this…

While in Panama at and Latin American I terceto Conference, II was grousing again to Carolyn about how we could see the US.gov snooping our customers through our li is to ATT. Carolyn said, “Ronnie, we start Internet companies, what can we start to block this surveillance?

So we decided the to start a VPN business and name it after the Golden Frog of Panama: GoldenFrog.com.

Like GigaNews, we have equipment and network all over the World.

With a VPN you can disguise your location since we have IP addresses for every country that has Internet.

I often pull a Brazilian IP address for my vpn location and within five minutes the Google ad borg starts sending me ads in Português so I know the Goog has taken my bait and is now selling my data a if I were a Brazilian !

VPN help confuse the Surveillance State.

I call a VPN, “ the 2nd Amendment for the Internet.

If you do t have one, get one ! “

I saw Jack a few years ago at a RPCV REUNION out in California.

We and our grown sons and 12 Grandchildren live in the Hill CountryWest of Austin.

Let’s get together?

We are pretty mobile.

Abraços,

Ron Yokubaitis

Thanks Ron. I remember when you and Bob visited during Micareta. Those were good times. I also retired last year and now live in San Anselmo, CA. Come visit anytime. Give my regards to Bob.

Tudo de bom meu velho amigo