NASA should focus on saving Earth–Follow the Peace Corps Example

Thanks for the “heads up” from Catherine Varchaver (Peace Corps HQ & Kyrgyzstan APCD/Ed & Acting CD 1990-97

Forget new crewed missions in Space. NASA should focus on saving Earth

By Lori Garver

Washington Post

July 23, 2019

Lori Garver is chief executive at Earthrise Alliance and was deputy NASA administrator from 2009 to 2013.

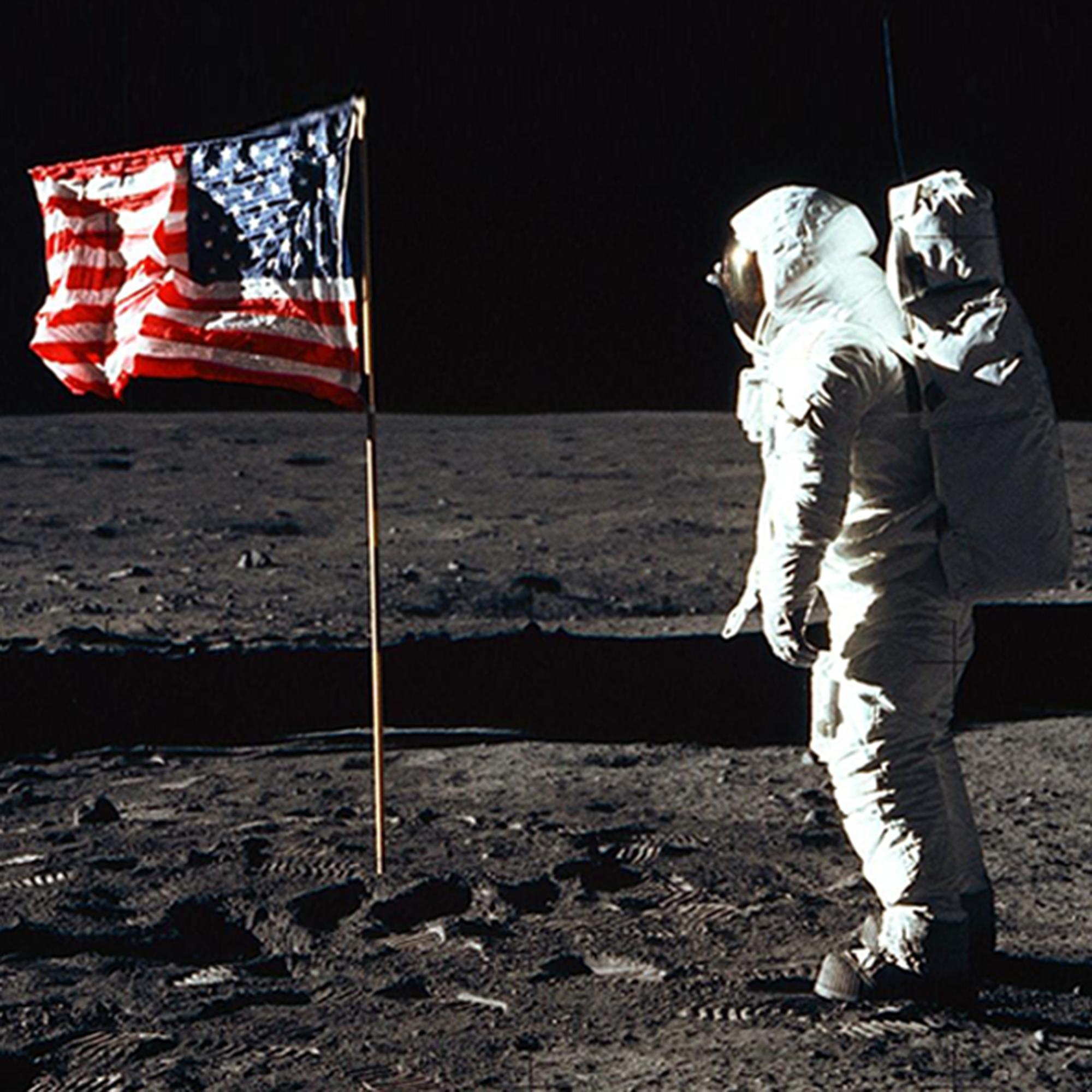

NASA was not created to do something again. It was created to push the limits of human understanding — to help the nation solve big, impossible problems that require advances in science and technology. Fifty years ago, the impossible problem was putting a human on the moon to win the space race, and all of humanity has benefited from the accomplishment.

The impossible problem today is not the moon. And it’s not Mars. It’s our home planet, and NASA can once again be of service for the betterment of all.

Let’s remember our history. We went to the moon 50 years ago in response to the Soviet Union’s perceived domination of spaceflight. The 12 Americans who walked on the moon brought back 842 pounds of lunar material (rocks and dust), learned about our closest planetary body’s geology and gave us a view of the Earth that changed our perspective. But that’s not what drove NASA spending to 4 percent of the federal budget in 1965. We were willing to stake so much on the moon landing — only because there was so much at stake.

After accomplishing this amazing feat, the aerospace community has again and again sought presidential proclamations to go further. President Trump is the fifth president to proclaim we will send humans to the moon and/or Mars within a specific time frame, a decree without a value proposition that has never inspired broad public support nor come close to coming true.

NASA remains one the most revered and valuable brands in the world, and the agency is at its best when given a purpose. But the public doesn’t understand the purpose of spending massive amounts of money to send a few astronauts to the moon or Mars. Are we in another race, and if so, is this the most valuable display of our scientific and technological leadership? If science is the rationale, we can send robots for pennies on the dollar. In a July Pew Research Center study, 63?percent of respondents said monitoring key parts of Earth’s climate system should be the highest priority for the United States’ space agency — sending astronauts to the moon was their lowest priority, at 13?percent ; 18?percent favor Mars.

With extreme weather ravaging parts of the country in recent weeks, climate change has become one of the most pressing public health challenge, American Public Health Associated Executive Director Dr. Georges C. Benjamin said. Drexel University Research Professor Dr. Shiriki Kumanyika added that people who are the least powerful and the most vulnerable often can’t rebound from the effects of the extreme weather cause by climate change.

The public is right about this. Climate change — not Russia, much less China — is today’s existential threat. Data from NASA satellites show that future generations here on Earth will suffer from food and water shortages, increased disease and conflict over diminished resources. In 2018, the National Academy of Sciences released its decadal survey for Earth science and declared that NASA should prioritize the study of the global hydrological cycle; distribution and movement of mass between oceans, ice sheets, ground water and atmosphere; and changes in surface biology and geology. Immediately developing these sensors and satellites while extending existing missions would increase the cadence of new, more precise measurements and contribute to critical, higher-fidelity climate models.

NASA could also move beyond measurement and into action — focusing on solutions for communities at the front lines of drought, flooding and heat extremes. It could develop and disseminate standardized applications that provide actionable information to populations that are the most vulnerable. NASA could create a Climate Corps — modeled after the Peace Corps — in which scientists and engineers spend two years in local communities understanding the unique challenges they face, training local populations and connecting them with the data and science needed to support smart, local decision-making.

The fragmented system of roles and responsibilities related to handing the massive amounts of Earth science data is severely hampering global efforts required to make significant progress. The U.S. government role in addressing this challenge is foundering without leadership. Standardizing data collection and coordinating its storage, analysis and distribution require experience working across disciplines, government agencies and universities as well as the private sector and international community. Only NASA has done this sort of thing before; only NASA has the credibility and expertise to do it again.

Assigning NASA this task would require an Apollo-scale change — but could be accomplished within its existing mandate and by shifting funding priorities. The National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958 supports expansion of human knowledge of the Earth and phenomena in the atmosphere and directs the agency to develop and carry out a comprehensive program of research, technology and monitoring to understand and maintain the integrity of the Earth’s atmosphere. The act requires NASA to work with other federal agencies, academia and the private sector to make the necessary observations, disseminate their results and enlist the support and cooperation of appropriate scientists and engineers of other countries and international organizations.

Apollo’s legacy should not be more meaningless new goals and arbitrary deadlines. Let’s not repeat the past. Let’s try to save our future. Besides, humanity’s intrinsic need to explore is driven by our need to survive.

The Peace Corps is not a magic bullet. It is not fair to presume Peace Corps has been successful and its systems could be replicated and applied to any problem.

“NASA could create a Climate Corps — modeled after the Peace Corps — in which scientists and engineers spend two years in local communities understanding the unique challenges they face, training local populations and connecting them with the data and science needed to support smart, local decision-making.”

The above is not a peace corps model for these reasons. I also think the Peace Corps experience could show the weakness of such a model.

1) The PC model uses Volunteers. How much would it cost to pay appropriately trained scientists and engineers to spend two years in local communities? Or, are there thousands of such trained scientists and engineers who would volunteer?

2) How long would it take to train such scientists and engineers in local languages and customs?

3) Where is the data and science to support smart, local decision-making? if such data exists, where has it been applied successfully in the United States?

4) Where would the money come from to support local communities? The US has just cut foreign aid to the NorthernTriangle countries of Central America which have been devastated by drought.

I believe are there are ways to proceed and Peace Corps could be a part of such an endeavor. But easy answers are destructive.

Mark Walker, who has posted here, has written an excellent article published in NPCA’s World View. I was able to read it online. Here is the link: https://www.peacecorpsconnect.org/articles/trouble-in-the-highlands

In no way, do I mean to suggest Mark Walker would approve of my comments. Probably, quite the contrary. Howeve his article describes in detail the complex nature and history of the problems faced in just one part of the world.

As someone who spent much of my professional career in high technology, I agree with Lori’s thrust but like Joane I am spectical that the Peace Corps model is the correct form. The model is NASA and the type of bright young people that were engaged in the Apollo program. Climate has to becme a focus as great as that if we are to survive.

I would tend to support NASA’s involvement in the scientific research associated with atmospheric chemistry and greenhouse effect, but share Joanne’s skepticism that a community volunteer program would not make much sense, as communities have NO direct control over the atmosphere, and the responses they DO have, like building flood-control dams, digging drainage canals, & cetera, are centuries old, well-understood by town officials, and not very scientific.

Where something along the lines of the Peace Corps COULD be instituted (and not by NASA, but maybe AmeriCorps and SeniorCorps) is a truly volunteer effort aimed at helping thousands of citizens, whose homes need fixing, after flood damage. We saw some of this already happening along the Texas Gulf Coast hurricanes and floods.

We could name it “Drywall Corps” ! ! And in all seriousness, I think that the feeling of accomplishment by such volunteers, working with the homeowners, kids with ideas about decorating their refurbished bedrooms, school officials &c would be VERY meaningful. Anyhow, that’s a comment from one of the Peace Corps’ earliest scientific PCV.s

John Turnbull Ghana-3 Geology and Nyasaland/Malawi-2 Geology Assignment, 1963, -64, -65.

Where is everybody ?? John T