“My Dona Anita” by Jerry Norris (Colombia)

A Writer Writes

My Dona Anita

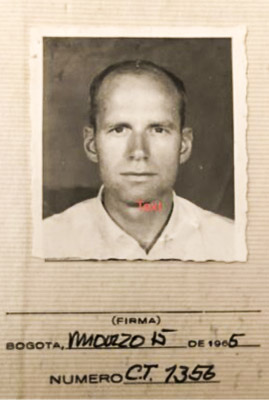

by Jeremiah Norris (Colombia 1963-65)

•

La Plata, Colombia

Early on in my stay in La Plata as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Colombia, an elderly woman made a habit of coming to my door late every afternoon. She appeared to be about 80 or so, was dressed in moldy, black rags with a shawl covering her head and most of her face, and she smelled heavily of urine. She had one or two badly bent front teeth, knurled hands, a deeply weathered face, walked uncertainly with a stick, hunched over and very slowly. She couldn’t have weighed more than 75 pounds. It pained her to look up at me as she was much less than 5 feet tall. She had to twist her head to one side and look up sideways when we spoke.

Once, though, she had been preceded into this world by a love story. Who were those lovers, what dreams did they have for their child, was she beautiful in her youth, did she have lovers, what great passions of the heart did they share, what were their hopes and aspirations, was there a path untaken, how did it lead her to a life of unforgiving impoverishment and social scorn? Perhaps she had been somebody from another time and place, someone people looked up to and respected.

The person who appeared at my door every day was not who she might have once been. I called her Dona Anita, though she never did tell me her real name. No one else seemed to know, either. She laughed when I used the term Dona. This title was never used because it implied some level of social status. She was the town beggar, a social outcast to all. She lived in a small lean-to up against the back of the Church about two blocks down from our house. It had been a tool shed. I could never see a bed in it; rather, there was a pile of straw off to one corner. It was no larger than a dog house with a high, sloping ceiling toward the rear.

At the appointed time in late afternoon, Dona Anita would rattle on my door, asking me in a thick, throaty voice to open it up. If I happened to be in a back room of our house and one of the other Volunteers opened the door first, she would refuse any help they offered. Dona Anita wanted Geronimo or no one else. She would never enter, with the exception of heavy rains, and only asked that I refill an old jar she carried about for daily water needs. It looked more like a delicate flower vase, though now dirty and cracked. Often, the jar was full. I would empty it, clean the jar off, refill it with fresh water, then press into her time-worn hands some cookies or candy or other food that we might have handy. As Volunteers, we were always conscious of not giving things to people, but doing things for them. She was always appreciative, looking up at me with watery, blood shot eyes, saying things under her breath, like this is our secret, I won’t tell anyone what you are giving me.

Although water and some companionship were the reasons for her stopping by, the most important request she had for me was to walk her home. If I was with her, boys and girls wouldn’t throw small pebbles at her as she stumbled slowly by. Apparently, in a very small town with little to do, this gave them some form of perverse entertainment. On most every day that I was in La Plata, I walked Dona Anita home. She loved it, often raising her stick up in defiance to her former tormentors, saying “I dare you to throw something at me now, eh.” It would take forever to get her to that hovel, as she leaned on me all the way. The boys and girls stood silently by and said nothing as we passed. On days when I was out late on the trail, one of Dona Lucia’s boys (from the house where we Volunteers took our meals) would sometimes walk her home, and ensure that no one bothered her. I never asked them to do this and they never told me that they had. Others would say “when you are not here, Dona Anita is being taken of by your friends. Soon, no one bothered her anymore.

I never gave a second thought to what I was doing with her, or why, and neither did my partners, Bob and Andy, ever questioned my motives. She simply became an accepted part of our daily lives as Volunteers. Sometimes, when I was down the street doing business at the time of her arrival, one of Dona’s Lucia’s children would come and get me, saying “your Dona is waiting for you.” The boys smiled when they said that. On days when Dona Anita did not appear at my door, I am ashamed to say that I failed to check in on her to see if she was o.k. Often, because my days became increasingly filled with new co-op activities, I didn’t notice her absence. It may have been on those days that she needed me most.

Soon, a new name started passing around La Plata — Santo Geronimo. I never liked it, playing it down, hoping the name would become a passing fancy. Still, it stuck. I consoled myself by not being pro-active with Dona Anita, and seeking her out when she didn’t appear at my door. I couldn’t escape the feeling that by overtly seeking her out I could very well be using her for my own purposes.

One day I went off to Popayan, and stayed for a long week-end. On my last day there, Dona Anita died and was buried within 24 hours. When I returned to La Plata, people would come up to me, expressing their condolences as if Dona Anita had been my mother. Maybe she was. My immediate mental picture of Dona Anita on being informed of her death was of a beautiful young girl in a plain white linen dress, laid out in a simple casket surrounded by fresh flowers of every kind. In my mind’s eye, I saw her rising up. “See, she exclaimed to those who had taunted her all these years, you let my outward appearance trick your eyes. I was once young and pretty and now I am forever.”

Jerry Norris

•

Jerry Norris was a Peace Corps Volunteer (Colombia 1963-65) where he developed agricultural cooperatives in rural areas of the country. Upon returning to the U.S., he worked in PC/W in its Public Affairs Office, and as Acting Director for its Office of Private and International Organizations. He currently serves as the Director for Hudson Institute’s Center for Science in Public Policy in Washington, D. C.

Thank you, Geronimo, for one of the most beautiful stories I’ve read on this site. You did more than represent the United States. You represented the human race at its best.

Patricia Taylor Edmisten, Peru, 1962-64

Patricia,

With an appreciation for your comment that will last until one day after forever.

Warmly,

Jerry Norris

Inspiring. Maybe every small town has its Dona Anita. In Chepen, Peru, my Dona Anita was Jose,. (I wish I had called him Don.) Once a week, he would stop me on the street and ask me where I had been because he had money a couple of days before and he had searched all over town so he could take me out for dinner. I told him it was the thought that counts, and I took him out for cafe con leche with a sandwich.

We were the town outcasts, I being the town spy, working for the CIA. Everyone knew it. And when I denied it, well, that was proof that I was. Jose never asked for money. He earned his” lunche” by telling me stories of his life. I like to think we were good for each other. Thank you Jerry for reminding me how much I learned from Jose.

Jerry:

This is a beautiful, heartfelt tale of love and wonder. Why did she single you out? It is the kind of story that would have become mythical, lasting.

Bill,

Neither then nor now do I understand why Dona Anita “singled me out”. Perhaps, because God does work in mysterious ways, it was, as you suggested, a mythical reflection of losing my mother at a very young age and then being raised in an orphanage. Subsequently, through another life in La Plata, she came back into my life where I could finally do something for her. Maybe that was why when Dona Anita passed away, residents of La Plata came to me, expressing their condolences, as if she had been my mother.

Warmly,

Jerry