“Justice for Pidgie D’Allessio” by Mary-Ann Tirone Smith (Cameroon)

Justice for Pidgie D’Allessio

by Mary-Ann Tirone Smith (Cameroon 1965–67)

I thought I’d finished writing, Girls of Tender Age, ten years ago. Then an email appeared in my inbox with a subject line so unexpected, so shocking, really, that it took me a few minutes to dare touch my fingers to the keyboard. First I went and poured a second cup of coffee, took a couple of gulps, sat down at my desk again and opened the message. The story was not over. A new ending was out there, a miserable one. I bought a new notebook and a box of Pilot G-2s, #10, Bold; I write all my first drafts in longhand.

The memoir centered on the murder of Irene Fiederowicz in Hartford, Connecticut. Irene was my friend, my neighbor, and my classmate. The last time I saw her was the day we went on our field trip to the Hartford Electric Light Company. We’d been studying electricity and learned that the first city in the United States to carry electricity to streets and homes was Hartford. My home today is where Thomas Edison built his winter getaway.

Irene and I planned to put a banana in our lunch bags. That morning our class climbed onto the chartered bus, so happy to have a day off from school. At lunchtime, we all ate our sandwiches, and Irene and I peeled our bananas together. Her mother had allowed her to bring a box of cookies to share. Irene passed the box around our table.

Late that afternoon, about an hour after Irene arrived home from school, her mother sent her off to the corner grocery store to pick up potatoes for dinner and replace the box of cookies. It was December 10, getting toward the shortest day of the year. Dusk was just beginning to darken the sky. Her mother told her it looked like rain, and if rain started, she should tie her scarf over her hair. Irene stopped at a house a few doors away to see if another friend of hers wanted to come along, but the girl’s mom said, no, that it was going to rain.

Irene never came home from the store. Her mother called the police. All night long, the police looked for Irene. So did her mother and brother Fred, who took turns searching for her or waiting by the phone. Early the next morning, in a back yard a few houses from mine on Nilan Street, a quarter mile from her home, Irene’s body was discovered by the family who lived at the property. She had been raped and strangled. The police didn’t look very hard.

Two weeks before Irene was murdered, a girl about to turn eighteen had been viciously assaulted a few city blocks from where Irene died. She survived. I gave her the name Pidgie D’Allessio to protect her identity.

The killer had demanded both girls not tell anyone what he’d done to them. Irene refused. Her last words reflected extraordinary bravery. She said, “I’m going to tell my mother.” He tightened the knot of her scarf twisted around her neck until she stopped struggling for her life.

In what could have been the last seconds of Pidgie’s life, he offered her the same chance to live that he had Irene. But Pidgie was not a little girl; she knew her only hope was to do what he said. Pidgie promised him she wouldn’t tell. He loosened then removed her scarf twisted around her neck and then began to act as if she were his date. She went along with his wanting to walk her home. Then he ran off. The minute she stumbled through her front door, she fell into her mother’s arms.

Her parents called the police. An officer arrived. Sitting between her mother and father on the sofa, Pidgie gripped their hands. It was difficult for her to speak; she was in pain from her physical injuries and her emotional ones. But she managed to tell the officer what the man had done to her. He then asked Pidgie what the marks were on her neck, and asked too, “Do you have a lot of boyfriends?”

His report stated that there was no rape as Pidgie told him she hadn’t been raped. (After the killer pulled off each girl’s pants and abused them, he ejaculated on them. Today, the acts Irene and Pidgie suffered constitute rape.)

The killer was Robert Malm, recently paroled after serving a short prison term for an attempted attack on another child in New London, where he served in the Navy. His parole board found him a job in a Hartford suburb.

Pidgie read of Irene’s murder the night of December 11th, in Hartford’s now defunct evening paper, the Hartford Times. Pidgie knew the man who nearly murdered her killed the little girl.

On December 12th, Pidgie and her parents went to police headquarters in downtown Hartford. She repeated all she’d told the officer who had come to her house, and added more details she’d come to recall, including the pack of Camels in Malm’s pocket. With that information in hand, the police took Malm — who’d become a suspect — into custody the next day, December 13th, at his place of employment, a nursing home in nearby Newington.

Within hours, Pidgie agreed to return to headquarters, where she picked Malm out of a line-up. He was immediately arrested for the attack on Pidgie. The police then began questioning him about the murder of Irene. Malm ceaselessly protested any and all accusations.

The next day, December 14th, Governor Abraham Ribicoff offered a reward of $3,000 for information leading to the apprehension of Irene’s killer.

On December 15th, the police promised Malm a bench trial rather than a trial by his peers if he would confess to Irene’s murder. They explained that a bench trial meant three judges would try him. The judges would not be affected by the details of the crime as would emotional jurors. He would likely escape the death penalty. Malm grabbed at the bargain. He then took the police behind the Nilan Street yard. He showed them where he’d left Irene’s body, saying he restrained her for about half an hour, during which time he tortured, raped and murdered her. Lying in the grass was a bag containing three potatoes and an unopened box of cookies.

Because the police did not believe what Pidgie had initially told the officer following Malm’s attack, she could not save Irene. But his capture, prosecution, guilty verdict, sentencing, and execution were entirely the result of Pidgie’s profound courage and the fortitude she maintained to bear witness against him, face-to-face, at his trial.

Robert Malm was put to death by electrocution eighteen months later.

When I came to write the memoir, my research revealed that Pidgie had claimed Governor Ribicoff’s offer of reward, but her claim was denied by the Connecticut Supreme Court. A court reporter would have transcribed those proceedings, but trial transcripts were copyrighted to the reporters. The reporters could sell copies of the transcripts, and if no one was interested they would often throw them away. They were not obligated to store them. Such was the case with the transcript I’d hoped to find But then I learned through an attorney friend that if Pidgie had gone on to file an appeal, the appeal transcript would become available to the public and would include the facts of the initial ruling.

At the Connecticut State Library, I scrolled through court records on microfiche for days on end. Then a copy of Pidgie’s appeal transcript appeared on the screen in front of me. The undeterred Pidgie had indeed filed an appeal. The basis for the denial of her original claim for the reward was appalling.

The lead judge in her case was the aggressively conservative J. Baldwin, former governor of Connecticut and later a United States senator. He determined that an offer of a reward was a contract, no different from a business contract. Since the reward—the contract—was dated December 14th, two days after Pidgie gave the police the details of the crime against her, and one day after she picked Malm out of a line-up, Judge Baldwin ruled she did not claim the reward in response to the offer; the offer hadn’t been made yet.

According to Judge Baldwin, Pidgie did not abide by the conditions of the contract. And where did the governor’s offer of reward make such a stipulation? Nowhere. The two other judges witnessing the proceedings concurred with him.

At Pidgie’s appeal hearing, Judge Baldwin denied her again in a determination beyond appalling; it was criminal, perhaps even unconstitutional. The basis for the denial of the appeal was a legal construct called “plain terms.” It means that the plain terms of the contract — words whose meanings are clearly understood — should be read literally, in a way that the attorneys who wrote the text of Governor Ribicoff’s reward offer did not intend. In fact, the legal definition of “plain terms” states that such a construct cannot be applied if the results are cruel and absurd; two perfectly plain words whose meanings are clearly understood. Judge Baldwin applied both in his ruling. The same two witnessing judges concurred as they had earlier.

This concept of “plain terms” has been called a travesty of justice by legal scholars, and recently, a fiction — a myth — by the Dean of the University of California, Berkeley School of Law, Erwin Chemerinsky, in an article he wrote that appeared in the ABA Journal. In arguments before the Supreme Court of the United States, he has demonstrated that “plain terms” relies on a court’s requirement to consider only the understood meanings of words, rather than the meanings intended by the lawmakers who wrote them. In Pidgie’s case, Judge Baldwin actually invented a plain term, calling an offer of reward a contract, which it is not.

The “plain terms” basis for a court decision is used almost exclusively to protect businesses from lawsuits, to allow attorneys representing those businesses to take advantage of victims who do not have the means to afford a defense against the so-called “plain terms” argument. Records show that ninety percent of these victims will not even appear in court, a slam-dunk for the attorneys. Business is business, money is money, and the victims of legal thievery are expendable. There are those who see themselves as above the law, cruelty and absurdity their pleasure.

The text of Judge Baldwin’s repulsive conclusion to his argument was, as follows:

An offer of reward … is not the recognition of an equitable duty of the government to the informer, but a mere act of public policy … whose terms are wholly within the discretion of the government. Whoever [makes a claim for such an offer] must bring himself within its terms. Failing to do that, his compensation is the consolation which comes to every citizen from the discharge of a public duty … the common obligation of all …. Courts must apply legislative enactments [meaning Governor Ribicoff’s reward offer] according to their plain terms.

Judge Baldwin had seen fit in his parting shot to lecture Pidgie with condescending derision, berating her for not appreciating that her consolation should not come from a reward, but from her public duty, which according to him, is an obligation. But Pidgie was consoled by performing her public duty, consoled by her hope that her testimony would prevent what happened to her from happening to other girls. This despite her public duty requiring she describe what a savage psychopath had done to her in front of a court packed with the general public. If Judge Baldwin had ever experienced anything of the horror that Pidgie had, perhaps he would not have relied on such cruel and absurd admonitions. Where does the Constitution say that the words he used to slander Pidgie were permissible? It doesn’t. In fact, asserting false, deceptive, misleading, or unconscionable means as were perpetrated by Judge Baldwin is prohibited by law.

After my memoir was published, I received hundreds of emails and notes from people with a connection to Irene, or to Hartford. What was overwhelming were the heart-wrenching letters from women with no connection except that they were also raped as children. These women never told anyone what happened to them because of the humiliation they felt. They told me.

The memoir, they said, relieved them of the burden of shame they carried. Good God, shame. Little girls who never received comfort, let alone medical attention, because society led them to believe that they’d done something shameful. And there were also women who did what Pidgie did, were faced with similar victim-shaming questions like the one the police asked Pidgie, and the most common: “What were you wearing when this happened?”

But Pidgie knew she should not feel shame, and she knew her parents would help her do what was right. They did.

And so, I received that email, the subject line: I am Pidgie D’Allessio’s son.

The youngest of Pidgie’s three sons, Joseph F., wanted me to know that he’d never heard of the crime against his mother, and only learned of it when, out of curiosity, he was checking a census for family names. His mother’s maiden name showed a connection to Malm’s case. Somehow — and I can’t imagine how — he came to tell his mother he needed to speak to her about something in her past. Now, the two haven’t stopped speaking about what happened to her, how it affected her and their loved ones.

She told Joe that when her book club was planning to discuss Girls of Tender Age, she realized that her rape was integral to the book. She quit the club. She never read the book, but a decade later her son did.

Joe’s email:

Dear Ms. Tirone Smith,

My wife and I have just finished reading your book, Girls of Tender Age. Thank you for writing it. It has affected me deeply, and my understanding of who my mother is.

I first learned of Robert Malm a few years ago when I was searching my mother’s maiden name hoping to find her in the newly publicized 1940 census. My mother and her family never mentioned Malm or her involvement in the case.

In some very profound ways, my mother has remained a teenager her whole life. I now understand why her development was stifled. She is 84 years old and will answer my questions about this terrible time directly and eerily without the emotion one would expect. I am pretty sure she distanced herself from emotions all those years ago.

I hope it is rewarding for you to know how impactful your work is and how telling Irene’s story continues to heal generations who weren’t even born at the time of her murder.

With gratitude and admiration, Joe F.

And so, moved by his words, I will conclude with a request to Derek Slap, State Senator, West Hartford, District 5; and Jillian Gilchrest, State Representative, West Hartford, District 18, presently representing Pidgie: Please introduce legislation creating a gesture of justice that will see to Pidgie receiving the $3,000 reward she was denied.

The same request to John W. Fonfara, State Senator, Hartford, District 1; Edwin Vargas, State Representative, Hartford, District 6; and Julio Concepcion, State Representative, Hartford, District 4. These men now represent the districts where Pidgie D’Allessio and Irene Fiederowicz lived the year they were attacked.

Pidgie D’Allessio was raped twice, once by an inhumane sadist, and then again by the state of Connecticut. This courageous teenager, who acted on her obligation to society — a society that treated her with obscene scorn — deserves a second reparation from Connecticut: an official apology from Governor Ned Lamont.

Note: Joe’s mother has agreed to let me make public her travails beyond the horror I described in Girls of Tender Age. I’d like to thank her for that and for allowing me to know that the real Pidgie grew up to live a productive life, to marry a good man, and to raise three fine sons.

If you want to help deliver justice to Pidgie, please show your support by calling or emailing the governor and legislators. Their contact information and sample messages follow.

Thank you.

Mary-Ann Tirone Smith

203-308-6353

Governor Ned Lamont, 860-566-4840

State Senator Derek Slap, District 5, Derek.Slap@cga.ct.gov, 860-240-4436

State Senator John W. Fonfara, District 1, John.Fonfara@cga.ct.gov, 860-240-0043

Representative Jillian Gilchrest, District 18, Jillian.Gilchrest@cga.ct.gov, 860-240-8585

Representative Edwin Vargas, District 6, Edwin.Vargas@cga.ct.gov, 860-240-8585

Representative Julio Concepcion, District 4, Julio.Concepcion@cga.ct.gov, 860-240-8585

•

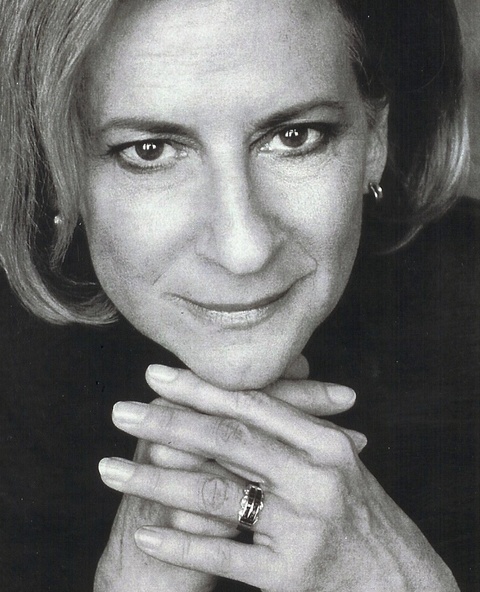

Mary-Ann Tirone Smith (Cameroon 1965-67) has published eight novels, and collaborated on a ninth with her son, Jere Smith. Her novel Lament For A Silver-Eyed Woman, published by Morrow in 1987 is the first novel about the Peace Corps by an RPCV. She has just published a new memoir FIRST YOU GET PISSED, on her website: www.mary-anntironesmith.com. She is now working on a crime story set in Florida where Mary-Ann now lives.

Mary-Ann Tirone Smith (Cameroon 1965-67) has published eight novels, and collaborated on a ninth with her son, Jere Smith. Her novel Lament For A Silver-Eyed Woman, published by Morrow in 1987 is the first novel about the Peace Corps by an RPCV. She has just published a new memoir FIRST YOU GET PISSED, on her website: www.mary-anntironesmith.com. She is now working on a crime story set in Florida where Mary-Ann now lives.

Dear Mary-Ann, Thank you for this and I will email the various politicians.

Also, everyone should go out and buy Mary-Ann’s beautiful and powerful GIRLS OF TENDER AGE. It’s a stunning book and each day it becomes more pertinent!

And how gratifying it must have been as a writer to receive Joe’s email!

Best, Marnie

This is so powerful. Thank you for all your advocacy. If we don’t live in Connecticut, should we still contact the politicians.

Thanks Marnie and Joanne.

Can’t hurt, Joanne!

I say share this article generally. Hit the share hand symbol to the right.

Thanks, Edward Mycue. I posted it to LinkedIn. Can’t post it to Facebook because they censored me; the material in my books and on my website do not meet their family values criteria. I received responses from many writers, who were also banned when they refused to cooperate.

Never knew this,very interesting.