LETTER FROM ECUADOR

Moritz Thomsen died in Guayaquil, Ecuador, on August 28, 1991. The official cause of death was listed as coronary thrombosis, but Thomsen had come down with cholera about two weeks before his death. He refused to go to a hospital and, during the last forty-eight hours, refused any and all treatment.

After his death, his close and good friend, Mary Ellen Fieweger wrote about Moritz Thomsen and his final days. The following is an excerpt from her letter to a friend of Moritz’s in California. It is reprinted here with the author’s permission.

First published in RPCV WRITERS & READERS in March 1992

His body was cremated, a wish he expressed a number of times over the years. This took place at the only mortuary concern in Guayaquil offering that particular service, Los Jardines de Esperanza, at the southern edges of the port city.

To get to the Gardens of Hope, you have to travel an unpaved, winding road lined with garbage dumps and surrounded by shanty towns. No doubt Moritz would have appreciated this touch, as well as the fact that because the oven was broken and the part needed to repair it could not be found, cremation was delayed for thirty-six hours, cause for concern in a tropical country where embalming is not practiced.

He would also have appreciated the fact that while the search for parts and the repair itself was going on–the search was in vain; someone finally improvised something–he was charged an hourly rental rate for the shabby mourning room where he rested in a chipped and dented coffin adorned with flowers rusting at the edges, accompanied by a pathetic band of five–Ester Prado, her children Ramon and Marta, one of her sisters, and me–not counting the quack of a doctor who during the past year made house calls during which she shot him up with vitamins and assured him that he was in her prayers day and night, these calls coinciding according to Moritz, with each new finances that came her way.

It wasn’t until she presented me with a bill for services rendered that I understood the good doctor’s solicitousness: those hours at the cemetery appeared on the bill; Moritz was covering one last financial crisis for her.

Finally, Moritz would no doubt have appreciated that, on the little sign board they put up at the entrance to mourning rooms–this particular sign board also rusting at the edges–his name was spelled wrong.

I don’t expect to meet ever again a human being as honest, as good as Moritz was. Sometimes he was hard on those around him, but he was always much harder on himself.

He lived his convictions quietly, daily; the hardest way, I think, to live convictions. In Living Poor he wrote, “You can’t move in too close to poverty, get too involved in it, without becoming dangerously wounded yourself.”

People I took to meet Moritz, who had read his books and wanted to know the writer, were often shocked by his material surroundings (or, better, lack of thereof) and later asked why he lived that way. After his death a friend suggested that his life was his way of teaching us something. I don’t think he intended to teach anyone anything; he was too modest to assume he had anything to teach. But that’s what he did, maybe in sprite of himself.

Moritz was often lonely, especially after he moved to Guayaquil because of hie emphysema and no longer had a circle of friends visiting daily. He said the hardest thing about being an expatriate was that everybody eventually left.

Letters, especially those from friends, meant more to him than you probably imagined. He pulled them out when I went to visit and asked me to read them. Sometimes, if the post office was on strike or there had been no mail, he pulled the same letter out on several visits, just to hear it again.

After he moved to the coast, I flew down about once a month. During the last couple of years, as his emphysema got worse, he left his apartment less and less. During the last six months, I don’t believe he went out a single time, not even to see the movies he wanted to see, because the effort involved in getting from the table he sat and worked and read as to the front door–five paces, maybe–was monumental.

He hated being dependent, even in little things, and I don’t think I ever succeeded in convincing him that, dammit, he wasn’t a burden, that there were people, like me, who felt eternally in his debt just because they had been privileged to know him, to become a friend, to read his books.

During the last year of his life he had begun to make notes for a new book, called From My Window. It was going to be a wonderful, sad book about what he had witnessed while sitting at his window, breathing in lead emissions and other contaminants, observing life in the heart of downtown Guayaquil.

Moritz is going to be missed by a lot of people, and the books he might have written by a lot more.

Mary Ellen was a very special friend indeed. Obviously, she considered herself one of, “those people who felt eternally in debt” to Moritz. I’d love to know who else considers themselves impacted by his writing and his life.

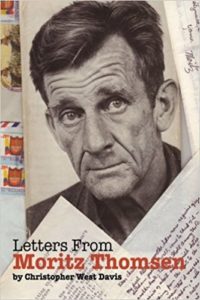

I’m enjoying Christoper West Davis’s, “Letters from Moritz Thomsen” which includes a revealing statement from Moritz about his success as an author, “Chris, dear boy, you DO know the right things to say and let’s face it, the starved ego of an unsuccessful writer is like the gaping mouth of a starved lion; it will gulp down and digest Anything.”

And yet many authors, publishers and readers consider his four books “masterpieces.” There’s a larger story hear about the man and his impact throughout and beyond the Returned Peace Corps world.