“How a Guinea Fowl Led Soldiers to Pound on My Door at 4 AM” by Curt Mekemson (Liberia)

First the story about the soldiers.

I’ve told it before in my book about my Peace Corps experience, The Bush Devil Ate Sam, and on my blog. Because it involved Guinea fowls, it deserves being told again. It was 1967 and I had just returned from my Peace Corps job of teaching history and geography at the nearby Gboveh High School in Gbarnga, Liberia. Much to my surprise — and dismay — I found soldiers standing in our yard pointing guns every which way. It was an ‘Ut-Oh’ moment. Liberian soldiers were scary.

“What’s up?” I asked, trying not to sound nervous. You learned early on not to mess with Liberian soldiers. There was a reason why the government refused to issue them bullets.

“Your dog ate one of the Superintendent’s Guinea hens,” their sergeant mumbled ominously. The Superintendent of Bong County was the equivalent to a governor except that he had more power. He lived a quarter mile away and his Guinea fowls strutted around on the government compound squawking loudly.

“Which one?” I asked innocently.

“What does it matter which Guinea hen the dog ate?” the sargeant sneered.

“No, no,” I responded, “I meant which dog.”

He glared at me for a moment and then pointed at Boy. I relaxed. It didn’t seem like the three Liberian dogs who had adopted Jo Ann (my first wife) and me would have done in the Supe’s Guinea fowl. They were three of the best-fed dogs in Gbarnga.

Boy was something else: A large, obnoxious, always hungry dog. He normally lived across town with Holly, another Peace Corps Volunteer. A second dog she owned, however, had puppies and drove Boy off. She was afraid he would eat her kids. Since Boy didn’t like Liberians, he had hightailed it across town to live with us. Normally I wouldn’t have cared. But given his attitude toward black people and the fact he thought of our cat Rasputin as dinner, I wasn’t fond of him.

“Why don’t you arrest him?” I offered hopefully.

“Not him,” the sargeant shouted. “You. You come with us!” Apparently, the interview wasn’t going the way Sarge wanted. A Liberian might have been beaten by then. I decided it was time to end the conversation.

“Look,” I said, “that dog does not belong to me. He belongs across town. I am not going anywhere with you.” With that I walked into our house and closed the door. It was risky but not as risky as going off with the soldiers. They grumbled around outside for a while and finally left.

Jo and I relaxed “small,” as the Liberians would say, but really didn’t feel safe until that evening. It was a six-beer night. Finally, around ten, we went to bed, believing we had beaten the rap.

WHAM! WHAM! WHAM!

“What in the hell was that?” I yelled as I jumped out of bed. It was pitch black and four o’clock in the morning.

WHAM! WHAM! WHAM!

“Someone is pounding on our back door,” Jo Ann whispered, sounding as frightened as I felt.

I grabbed our baseball bat, headed for the door, and yanked it open. Soldiers were everywhere. The same friendly sergeant from the afternoon before was standing there with the butt of his rifle poised to strike our door again.

“Your dog ate another one of the Superintendent’s guinea hens,” he proclaimed to the world. I could tell he was ecstatic about the situation. He had probably tossed the bird over the fence to Boy.

“This time you are going with us!” he growled.

In addition to being frightened, I was growing tired of the routine. “I am sorry you are having such a hard time guarding Guinea hens,” I said, trying to sound reasonable, “but I explained to you yesterday that the dog does not belong to me and I am not going anywhere with you. Ask Mr. Bonal (the high school principal who lived next door) and he will tell you the dog is not ours.”

Sometimes the ballsy approach is your best option.

I closed the door and held my breath. Sarge was not happy. He and his soldiers buzzed around outside like angry hornets. Still, yanking a Peace Corps Volunteer out of his house and dragging him off in the middle of the night over a guinea fowl could have serious consequences, much more serious than merely reporting back that I was uncooperative. I could see the headlines:

Soldiers Beat Peace Corps Volunteer Because Dog Eats Guinea Fowl. Liberian Ambassador Called to White House to Explain

I hoped the sergeant shared my perspective. At a minimum, I figured he would check with Bonal. John might not appreciate being awakened in the middle of the night, but it would serve him right for laughing when I had told him the guinea fowl story the night before. Anyway, I suspected he was up and watching the action.

We had a very nervous thirty minutes before the soldiers finally marched off. In the US, this is the point where we would have been calling an attorney, Jo’s mother, and the local TV station. Here, my only backups were the Peace Corps Representative and Doctor: one to represent me, the other to patch me back together.

Happily, our part of the ordeal was over. It turned out that Peter, a young Liberian who worked for Holly, actually owned Boy. The soldiers finally had someone they could bully.

Peter was pulled into court and fined for Boy’s heinous crimes. Boy, in turn, was sold to some villagers to cover the cost of the fine. As for Boy’s fate, he was guest of honor at a village feast. Being a Bad Dog in Liberia had rather serious consequences.

•••

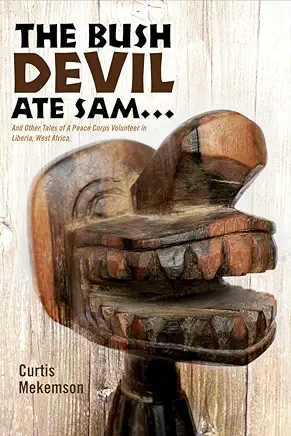

The Bush Devil Ate Sam… : And Other Tales of a Peace Corps Volunteer in Liberia, West Africa

The Bush Devil Ate Sam… : And Other Tales of a Peace Corps Volunteer in Liberia, West Africa

Curtis Vern Mekemson (Liberia 1965-67)

200 pages

BookBaby 2014

$11.22 (paperback), $3.99 (Kindle)

Great story. Reminds me of when I lived on an experimental/model farm of the Colombian Federation of coffee growers and the Mayordomo of the farm came pounding on my door at 3:00 AM. He shoved a 38 in my hand and told me the bandoleros (guerillas) were out in the coffee grove. Off we went to defend the farm. Happily, the bandoleros took off and there was no firefight. I did pause to ask myself “What am I doing here”?

Great Story Curt – I am amidst getting my journal into a story. Liberia Pleebo City Maryland County – 1987-1990 Fisheries and Agriculture.

Peace Corps inspired me to found Ecologist Without Borders