God, President Kennedy, and Me (Tonga)

God, President Kennedy, and Me

by Tina Martin (Tonga 1969-71)

A version of this appears in the anthology Even the Smallest Crab Has Teeth, 2011.

I remember what I was doing on November 22, 1963 even before I heard that President Kennedy had been assassinated. Praying. Not just because I was chairman of Religious Emphasis Week at Columbia High School but because there was a beauty contest that night and, if it were God’s will, I was willing to win it. So I kept checking in with God, letting Him know that He was on my mind, and I sure hoped I was on His. I didn’t want Him to fix the contest. That wouldn’t be fair. I just wanted Him to help me do justice to whatever God-given beauty I might have so that I could honor the Future Teachers of America Club I was representing and serve as a good example for whoever needed one.

“Dear God,” I whispered, “tonight’s the night. If it be Thy will for me to wear the crown of Miss Columbian, Thy will be done, and”—I added with special emphasis—“I’ll give my first summer paycheck to CARE and the NAACP.” (In summer I worked in Central Supplies at the South Carolina State Hospital, where my father was Chief Psychologist, but I was too young to work on the wards, so I cleaned needles and syringes instead. I also baby-sat for fifty cents an hour, double what I’d gotten in previous years.)

Living in The South in 1963, I was (1) in the habit of praying in and out of school and (2) in—and out of— beauty contests. We had them for everything, even Fire Prevention Week, and at the urging of my prettier and older sister, Dana, who won the Miss Columbian Contest when she was only a sophomore, I’d decided to work on being prettier than me, if not prettier than her, and carrying on the family tradition of winning even though it couldn’t be in my sophomore year. I’d won the Miss Freshman contest my first year of high school, been eliminated in no time at all in my sophomore year, been eliminated eventually in my junior year (bad perm) and now I was already a senior. Last chance.

It was when Dana clearly wanted me to win that I first knew she could be nice, this sister of mine, who’d previously just cursed my birth, beaten me up, taken my lunch money, and made fun of everything about me that was ridiculous, and there was plenty. But now she actually wanted to help me win. To this very day I don’t know why.

People sometimes told me that I looked like Natalie Wood and occasionally like Mary Tyler Moore in The Dick Van Dyke Show, but Dana looked like Elizabeth Taylor back in the days when that was a good thing. She had the same oval face, perfect nose and teeth, same-shaped eyebrows. The only thing that wasn’t quite the same was the black hair. Dana’s hair was really medium brown, but she was not about to be medium anything, so she’d started dying it jet black after she’d first seen Elizabeth Taylor in Raintree County in 1957, the year people started noticing the similarity. That was probably the year she took over the upstairs bathroom, too, to do her chemistry lab work for beauty. Six of us used the bathroom downstairs, and she used the one upstairs, where the sink was always stopped up with mysterious make-up-hair stuff. But however horrendous the bathroom was, she was beautiful. She’d also been dressing pretty much like Elizabeth Taylor in Raintree County, which made people think she was a strange beauty because Raintree County was a period piece. Not that she wore bonnets or anything. But when other girls were wearing matching cashmere sweaters and straight skirts, she was wearing full skirts and lots of crinolines more reminiscent of the War Between the States, as Southerners called the Civil War back then. The War Between the States: The South’s Fight for Independence.

In our family, we called the War between the States the Civil War because, as my friend Sara cautioned people when she introduced me, “Tina’s not from here.” That’s why I was bribing God with my summer wages, promising to give my first paycheck to CARE and NAACP, which my Southern friends dismissed as Communist and against State’s Rights. I thought my parents knew better than my peers because they were much older, closer to God’s age.

To help along bribe-induced divine intervention, Dana was going to come back to Columbia from Winthrop College in Greenville to help me win the contest. She’d picked out the pattern for the dress I was going to wear and helped Mother find the material at the remnant store because one of Daddy’s strongest convictions was that we shouldn’t spend money. He would give Mother a budget, for which she’d create envelopes, and she’d put five or ten dollars in each envelope, but sometimes she’d have to borrow from the clothing envelope for the food envelope and vice versa. Daddy was Chief Psychologist at the South Carolina State Hospital, President of Southern Psychologists and had a class of graduate students at the University of South Carolina, but the friend I felt I had the most in common with was Glennis, whose father was a shoe repairman, because Glennis and I both lived poor.

Dana said that with beauty, we could rise above poverty, and beauty was her greatest talent. She knew just how to get my hair to look like Jackie Kennedy’s, and I knew I was lucky that she was doing this for me, but I wasn’t counting on luck or Dana. I was counting on God, which was why I was praying more than usual that day.

“Please, dear God, if it be Thy will.”

The minimum wage had gone up to $1.15 an hour, and I would give all my first pay check to these good causes if God would support my cause and let me win the crown. It hurt me, I told God, that not everyone believed in His existence the way I did. And it hurt me, too, that not everyone believed in the existence of my God-given beauty the way I prayed the judges would. Being beautiful—at least for one night—would be an answered prayer.

“A thing of beauty,” I said, paraphrasing one of the poems I’d memorized to make up for being bad at math, “would be a joy forever.” I wanted to bring joy to the world and prayed that I could do it this special way.

Of course, other girls prayed. This was The South, after all. But their prayers were shallow. Mine had depth because I had a social consciousness, which I figured God had too. That was one of my advantages in the beauty contest. I had a better idea of what God wanted, though it never occurred to me that He would want Negroes in our beauty contest. Of course, there weren’t any Negroes at our school.

“It’s been a decade since the Brown vs. Kansas,” my mother would say, “and there’s not a face that isn’t white at that school.”

“Or at any other,” I’d say. I knew that Columbia High School was no more prejudiced than any of the others. Most Southerners thought the Supreme Court had been infiltrated by Communists, and the government was going to take over and destroy our way of life. People in South Carolina were saying that President Kennedy and his brother had already gone to Mississippi and Alabama totally disregarding State’s Rights, and they’d probably be coming here, but until they did, it was going to be Separate But Equal. Separate water fountains. Separate parts of the bus. Separate schools, and of course, separate beauty contests for the whites and the coloreds, if they had beauty contests.

I knew even back then that “whites and coloreds” sounded like socks, but black was a term reserved for Stephen Foster songs like “Old Black Joe.” Black was not yet beautiful. But that night I would try to be. Though I occasionally tried to rise above such petty aspirations, that night, with God’s help, I would indulge in and achieve them. Once I’d gotten being beautiful out of my system, I assured God and myself, I could spend my time praying for the outcast. But tonight I would reserve my prayers for me—that I not be cast out—at least not until after I’d made the finalists. I knew beauty was but skin deep, but tonight skin deep got crowned. Skin deep got a dozen long-stemmed roses. And most importantly, skin deep got two full pages in our high school yearbook.

I didn’t really have to win that contest to take up more than my share of space in the high school yearbook. I’d been a dismal failure in junior high school, where I’d gotten a bad reputation for wearing red lipstick the first semester of seventh grade when all the good girls waited till the second semester and started with pink, not red. Everyone in the car pool on Stratford and Sheffield Roads and at Miss Sloane’s Dance Class had agreed on the second semester. But Dana had told me that I needed color, so my bad reputation was her fault, and maybe also the fault of Nancy Todd, whose brother I’d let kiss me when I was working on a science project at her house, and she’d told people that I’d kissed back! Then he’d started riding to my house on his motorcycle, and since I looked a little bit like Natalie Wood, it was Rebel without a Cause. People thought I was fast and cheap, and I lived in a neighborhood for nice girls who went to Hand Junior High, where girls like me were ostracized and left to the boys they let kiss them. But I never “went all the way” or even half of the way with Greg. We never even went steady. Greg was a local boy, and until I met Steve, I was holding out for a foreigner, like Jean-Paul, the French exchange student at Columbia High School.

Fearing that my kissing back had gotten me a bad reputation in junior high school, I’d over-compensated in high school—even switching from Dreher and A.C. Flora, our neighborhood schools, to Columbia High School. I’d learned that success consisted of being like everybody else, only better, and God willing, prettier. I’d almost learned how not to be weird, not to look too eager. I’d learned how not to dress. (Not in my wilted, smelly gym blouse just because I could never get my locker open. Not with my bobby socks crawling down into my loafers.) I’d even learned how to open my locker. I’d learned when to help others and when to help myself. I’d read Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People at Myrtle Beach the summer before I began high school, and I’d begun my negotiations with God.

Gradually I had become socially acceptable—even decent. I was the DAR Girl and Chairman of Religious Emphasis Week. I’d won second-place in the city-wide Youth Leadership Contest sponsored by the “benevolent and protective order of Elks.” I’d accumulated awards and been elected to school offices. Now I was a member of Executive Council and the Editor of the literary yearbook, The Rebel. This was a big turn-about for a girl who’d been nominated for an office only once in junior high school and had broken out in a cold sweat because she feared the only vote she’d get was that of the kid nominating her. She was right. The teacher forgot to erase the board, and I saw it with my own eyes.

Homeroom Coupon Chairman

Frances: 10

Pat: 16

Tina: 1

Did I mention that my name is Tina?

But now in my senior year of high school, I was president of two clubs, the Anchor Club, a girls’ service organization, and Future Teachers of America, which was sponsoring me in the beauty contest that night. If I won, in a way it would be a boon to American education. But I have to admit, it wasn’t just for that that I wanted to win. I wanted to win so that I’d have a permanent record of how I was before I started to grow old. Dana always said that from the age of sixteen, we start to die a little bit every year. “Nothing can bring back the hour of splendor in the grass, glory in the flower,” Dana said, “So gather we rosebuds while we may.” I wanted a two-page spread of how I was before I started to wither and wilt.

Dana had told me to cut classes that day so she’d have longer to work on me—after all, she was cutting a day of her classes at Winthrop College to come home to help me— but the principal had a new policy. He saw how girls were absent from their classes to have their hair done on the day of the beauty contest, so this year he’d announced that roll would be taken, and any girl absent from any of her classes would be ineligible to compete in the Miss Columbian Beauty Contest. So Dana agreed to start in on my Jackie Kennedy “do” right after school got out. That would not only save one dollar and fifty cents (the price of a wash and set), but that would mean my beautician would be a beauty queen personally dedicated to my being one too.

Before I left for school that morning, I caught my mom reading when she was supposed to be working on my dress.

“What’s the Feminine Mystic about?” I asked her.

“It’s Feminine Mystique,” she corrected me. “Mystique comes from French.” She pronounced the word French with a reverence she’d taught me to feel. “It’s all about the sacred feminine ideal.”

I’d nodded. I had a sacred feminine ideal: God willing, I’d be the prettiest girl of all—please, dear God, just for one night. If mother ever finished the dress!

When Dana woke up, she could keep Mother on task while I was in school. Dana had driven up the night before in the little Fiat Daddy bought her because he wouldn’t support the re-industrialization of Germany by buying a VW, and she and I had had a little bit of time to confer on how I should walk, how I should smile, and things like that. She’d been nice until she just had to ask that question she’d been taunting me with all semester.

“How’s your campaign going?”

“What campaign?”

“You know. The one for the highest possible moral standards award?”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“Yes, you do!”

“No, I don’t!” I said. I looked at her as if she were crazy and as if I had a low tolerance for the insane.

But I knew. She was talking about the Bill Goldelock Scholarship, which was awarded to a high school senior every year. Bill had once been the president of the student body at Columbia High School, and then he’d been killed in action in Korea. In his memory they gave an award to the senior who most exemplified the characteristics he embodied: Service, leadership, and the highest possible moral standards.

They didn’t have the term “short list” back then, but if they had, I’d have been on it. Unless they found out about how fast and cheap I’d been in junior high, kissing back!

Mother put down her book and told me to try on what she’d sewn together so far.

My gown was long and straight—something like the one Jackie had worn when she’d gone to France with President Kennedy and he’d introduced himself as “the man who accompanied Jacqueline Kennedy to Paris.” Jackie had spoken French with President De Gaulle. Someday I’d know French too. I’d join the Peace Corps right after I finished college and I’d go to some French-speaking country and learn French while I did good deeds. Soon I’d be doing good deeds in French!

“Are you sure this is going to be ready by tonight?” I asked my mother.

“Don’t worry. It’ll be ready,” Mother said through the pins between her front teeth. I remembered how I’d had to wear pins in my clothes on the occasions when my formal wasn’t ready—like for the junior-senior dance the year before.

“Please God, please,” I prayed silently. “Let it be ready by tonight. Help Mother focus.”

There were few occasions when I didn’t turn to God, and I prayed silently all the way to school. After our classroom prayer during homeroom period, I added my own silent P.S. “If it be Thy will…”

People came by me at my hall monitor post, and a lot of them said, “Good luck tonight.” I looked back at them quizzically, as if the beauty contest were the furthest thing from my mind.

“Why don’t you get your hair fixed like Laura Petrie on The Dick Van Dyke Show?” someone asked. “You already look a little bit like her.”

“But it wouldn’t be right to copy her,” I said, adding with a resigned shrug, “I just have to be myself.”

And my self was going to be Jackie Kennedy. Dick Van Dyke was cute, but I wasn’t settling for him. I was going to be the President’s Wife, the one he took to Paris.

I walked by the auditorium where we’d be having the contest in just a few more hours. The faculty sponsor of the yearbook, Miss Carter, had vetoed the students’ vote for “The Days of Wine and Roses” as the theme because she said it wouldn’t be seemly to have wine bottles decorating a high school stage. So tonight we’d hold crescent-shaped cards bearing our numbers, and “Moon River” would play as we walked across the stage—the same stage where Strom Thurmond had stood while getting a standing ovation earlier in my high school career, when the Key Club boys had invited him to speak. I had stood and applauded, too, because even though I disagreed with everything Strom Thurmond stood for, I didn’t want to stand out by not standing. I knew I would probably not have made President Kennedy’s Profiles in Courage, but how many of the men in that book had been rejected for Homeroom Coupon Chairman? How many of those men had kissed back in junior high school and gotten a bad reputation? I had a past to rise above, and I didn’t want to alienate my Southern friends. I knew their fears.

In spite of Strom Thurmond’s stand against civil rights, the Civil Rights Bill might become law, and if it did, those Kennedy Brothers would enforce it, forever changing the Southern Way of Life. We didn’t know yet that Sidney Poitier would win the Oscar for “Lilies of the Field” during our senior year of high school, being the first “colored person” ever to win an Oscar. He’d be up there on stage with Patricia Neal, a white lady, and they’d be hugging each other, which was worse than what I’d done with Greg Todd. Greg was white. Hadn’t Perry Cuomo kissed Earth Kitt right on the mouth? The world was on its way to miscegenation!

Just three months before our beauty contest, there’d been that big civil rights march in Washington with more than 200,000 people showing up and hearing Martin Luther King talking about making all people equal no matter what color their skin. If God had wanted all people to be equal, my friends reasoned, wouldn’t He have made them equally white? And then President Kennedy had sent troops to Alabama to force an all-white school to accept two colored girls, and they’d enrolled in spite of Governor Wallace’s rallying cry to protect States’ Rights with “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” If President Kennedy hadn’t given that speech saying Civil Rights was a moral issue, that White Council guy might not have had to assassinate the head of the NAACP.

The federal government was becoming Communist and taking over the country, stirring discontent into the heads of colored people who had been perfectly happy before.

It was at the beginning of the school year that those four little girls had been killed by a bomb planted in their church, and that’s when I heard my parents talk about the NAACP, but I certainly didn’t let my classmates in on my promise to God that I’d give my first pay check to the NAACP if I were chosen our school beauty queen. I didn’t think God was a Southerner—though I never told my Southern friend I didn’t. The leader of the NAACP had been assassinated in June, and four Negro children had been killed in a church bombing in Birmingham. I had a hunch that God didn’t buy that thing about the NAACP being Communist. I was counting on His being pleased with (and maybe persuaded by) my donation!

I don’t remember any of my morning classes; I assume I prayed my way through them. But I do remember Miss Pearlstine’s Problems of American Democracy class after lunch that day because that was when the news came.

Miss Pearlstine was my favorite teacher. She was a Democrat, too, at a school where the principal himself—Mr. Kirk, an otherwise nice guy who’d coached football before coming to our school—had started The Young Republicans Club, which he himself was sponsoring. The South had finally caught on that the Republican Party was no longer the party of Lincoln, who had done such terrible things to the South. The parties had switched, and the South was turning away from the Democratic Party. In fact, there was no Young Democrats Club at Columbia High, and Miss Pearlstine had protested.

“If you think the school should have a Young Democrats club,” Mr. Kirk had told her, “you’re free to start one.”

But she wasn’t free. She was already the sponsor of the International Relations Club, of which I was president. She was one of the few people who was enthusiastic about my plans to join the Peace Corps as soon as I finished college, culminating a five-year plan that only began with tonight’s beauty contest.

Miss Pearlstine was the only Jew at our school. As chairman of Religious Emphasis Week, I thought of her and suggested that we drop the “in Jesus Christ we pray” part of our prayers so she wouldn’t feel left out. But Miss Webb, the sponsor of Religious Emphasis Week, said, “I’m sure she doesn’t mind if we pray our way when there are so many of us and so few of her.”

Close to the beginning of our 1:15 class, Mrs. Lindler, a math teacher who had an Algebra by TV class, came to the door.

“You know what?” she said. “They interrupted our Algebra lesson for a news bulletin. There’s been some shooting around President Kennedy’s motorcade in Dallas.”

“Oh, how awful!” Miss Pearlstine said. “I hope nobody’s been hurt.”

I dropped God a quick line.

“Dear God, let everyone be all right.”

But I felt sure that no one had been hurt—not seriously, if at all. I was so certain that President Kennedy was all right that I felt foolish wasting my prayers—prayers that should be directed towards the less certain outcome of the night’s beauty pageant.

We went back to our lesson about voting precincts. And then the principal came over the PA system.

“President Kennedy has been shot,” he said. “We have not yet received word on whether or not the shot was fatal.”

Fatal? Of course the shot hadn’t been fatal. Why was Mr. Kirk being so melodramatic? Presidents didn’t get assassinated nowadays. Not in our country. Maybe he’d been shot at. I could picture him in a Dallas clinic now, charming the staff as the nurses bandaged a slightly nicked shoulder.

“I had hoped for a 20-gun salute,” he might say, “but not directed at me.”

That night I was going to look like his wife. The time he took her to Paris.

A few minutes later Mr. Kirk came over the PA system again.

“May I have your attention please?”

He had our attention.

“President Kennedy is dead.”

There were cries and gasps of disbelief. Jeanne Thigpen began to cry. I turned to her.

“It’s not true,” I told her. “I know it’s not true.”

A couple of students cheered.

“He asked for it,” a guy named Sam said. “He was practically becoming a dictator.”

“I think he was a good president,” Miss Pearlstine and I said in unison. Was?

“This proves that God didn’t want a Catholic president,” Sam continued.

“Oh, shut up!” I said. And then I remembered my responsibility as a possible future Miss Columbian, and I added, “Please.”

I still couldn’t believe that President Kennedy was dead. Reporters made mistakes. They were almost always wrong about the weather.

“Dear God,” I prayed silently. “Let President Kennedy really be alive. Make this news a false report, and I will give up being Miss Columbian.”

I paused for a moment. I knew I had to go further still.

“I’ll even give up being among the finalists.” I added silently.

In sync with my prayers, Mr. Kirk continued.

“There have been some questions about tonight’s beauty contest. If this was a frivolous affair, we would cancel it. But it’s been planned for a long time, and the publication of the yearbook depends on the money we raise tonight. So the contest will go on as planned.”

I convinced myself—sort of—that since I was representing the Future Teachers of America Club, it was my duty to participate in the contest. I decided I would go on, but I wouldn’t smile—not unless the news was false and Kennedy was really still alive. Then I would go on and I would smile but, in keeping with my vow to God, I wouldn’t win. I wouldn’t even be among the finalists.

It was while Dana was teasing my hair to make it look like Jackie’s that we received a phone call from the school secretary.

“Some of the judges don’t feel like coming,” the secretary said. “So the beauty contest will have to be postponed.”

Mother stopped working on my dress, and Dana stopped working on my hair, and we all sat down in front of the TV and watched a disheveled Jacqueline Kennedy stand beside Lyndon Johnson as he was sworn in as our next president. She had a dark smear on her dress, and even though we didn’t have a colored television, we knew it was blood. She’d taken his head in her lap and then she’d crawled over the open limousine to get help.

“Now you look more like her than she does,” Dana told me.

We all spent the weekend right there in the den, watching all the Kennedys. Caroline, who’d once come to her father’s press conference in her mother’s high heel shoes, was now crying as she held her mother’s hand. John John, sometimes photographed romping around in his father’s office, was now saluting our dead president’s flag-draped coffin. But the biggest change was in what they were saying about Jacqueline Kennedy. No one was talking about her sable underwear or who had designed the dress she was wearing or how much it had cost. All anyone noticed about her dress was that it wasn’t the pink suit with the bloodstains on it. It was all black. A black mantilla replaced the pill-box hat. They were using words like courage and dignity. Everything had changed, and I decided I had too.

As Dana was getting ready to drive back to Winthrop, she said, “I came home for nothing.”

“Well, you were here to watch President Kennedy’s funeral with us,” I said.

“But that’s not something only I could do,” she replied, as if she were a fairy godmother robbed of her mission. “Well, when they reschedule the beauty contest, let me know the new date, and I’ll see if I can come down.”

“Thank you, Dana,” I said, “But I’m not sure I have my heart in things like beauty contests anymore.”

“Oh, that’s right. Now all you care about is the Highest Possible Moral Standards Award.”

On Monday morning, Mr. Kirk came over the PA system once again. He gave us the new date for the beauty contest.

“And now, let’s have a moment of silent prayer,” he said, “for our country and in memory of President Kennedy.”

That’s when I realized that in spite of what had happened, I still cared about the contest, and even though my silent prayer was all about Kennedy and his family and the nation (I was, after all, DAR Girl), I had to add a little PS about the contest. I was too ashamed to ask God to help me win it, with President Kennedy up there within earshot. Still, I had to ask God for something. I knew He would be waiting.

“Dear God,” I told Him silently, “I guess, the way we left it, I could ask You to help me win this contest because I only offered not to win if Kennedy didn’t die, and he died. (I refrained from saying, “You let him…”) But, even though we’re back where we began, I’d like to move forward and do something to honor Kennedy.” I didn’t mention anything about meeting foreign men and seeing foreign lands and learning foreign languages like French. I didn’t want God to think I had ulterior motives.

“When the time comes and I’ve finished Winthrop College and have my BA in English, could you and President Kennedy help me get into the Peace Corps?”

It made me a little bit nervous when, on the postponed date of the contest, I won. Did that mean that God was behind in answering my prayers or that He’d chosen having me crowned over getting me into the Peace Corps?

I had no idea that exactly twenty-five years later, I’d be standing in the Capitol Rotunda with 399 other RPCVs reading entries from the diaries we kept during our service, commemorating President Kennedy’s greatest legacy, the Peace Corps. It was a peaceful “occupation” of the Capitol back then that the press covered. In fact, the following morning, I asked my father “Are you familiar with USA Today?” and he said, “Yes. It’s a piece of trash.” “Well,” I told him, “I’m on the front page today.” “Great!” he said.

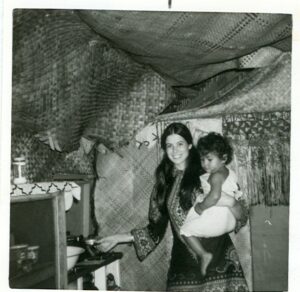

After Tonga (1970-71), Tina used her readjustment allowance to move to Spain, where she studied French. She then joined International Voluntary services to teach in Algeria for two years, after which she returned to the USA, married, had a baby (now 43-years-old), and taught at City College of San Francisco for thirty-two years. She is the author of three memoirs, Everything I Should Have Learned I Could Have Learned in Tonga, Letters from Algeria and the Day Everything Changed, and Letters of Apology for My First Memoir.

I love this story as much today as when I read it the first time. Wonderful.

Thank you so much Jane! I credit your anthology at the beginning. I’m glad that John has resurrected it this 60th year since President Kennedy was assassinated, and I added a tiny bit about the Journals of Peace, which meant so much to me. I just hope anyone who reads it sees it as humorous and self-mocking rather than as just “retro,” with words like “Negro” and “colored” and all that bribery of God and obsession with a beauty contest.

What a poignant, humorous, and well-written story. It never gets old.