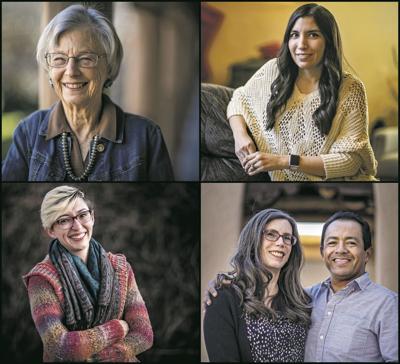

Global mission launches lifetime of volunteerism for many

By Michael Tashji, Santa Fe New Mexican

Dec 12, 2021

–

–

Children in Borneo in the 1960s were admitted into school when they were old enough to reach their arm over their head and touch the top of their ear.

“If you were older than [5 or 6], it reaches farther, and if you were younger, it didn’t quite come that far,” said Mary Jo Lundy, 81. “There was no birth certificate.”

The Santa Fe resident and her then-husband, Dudley Weeks, were among the first Peace Corps volunteers to go to British North Borneo in 1962, where she taught kindergarten and he taught third grade.

“We were moved by President Kennedy’s vision, proud of what the Peace Corps stood for and excited that we would be part of this effort to bring peace and understanding to the world,” Lundy wrote in a self-published memoir this year titled Coming Full Circle: Listening to My Life.

Lundy is one of hundreds of Peace Corps veterans in Santa Fe — and perhaps thousands in New Mexico — who have served since the corps was established 60 years ago. President John F. Kennedy signed the executive order creating the volunteer corps March 1, 1961, and it was authorized by Congress in September of the same year. Since then, more than 240,000 Americans have served in 142 countries.

Returned Peace Corps volunteers often stay connected through the National Peace Corps Association, which advocates for the corps’ mission and lobbies Congress for continued funding.

The group has a branch in New Mexico with about 1,000 members, including Lundy and more than 200 others who live in Santa Fe.

“We organize events that bring people together around service,” said Greg Polk, a member of the state association’s coordinating committee. “We’ve done trail clearings in the national forest, cottonwood tree plantings in Albuquerque, [and] river cleanup projects in Albuquerque and Las Vegas.”

The group also helps nonprofit and social service organizations with their facilities upkeep.

Four years ago, the association launched a grant program to fund volunteer-initiated projects.

Lundy is one of its earliest-serving Peace Corps veterans.

She graduated from Southern Methodist University in May 1962, and two weeks later, she and Weeks arrived at the University of Hawaii to train for three months. Lundy, who was 22 at the time, still has the Western Union telegram congratulating her for being chosen to participate.

Borneo is an island in the Pacific Ocean that sits on the equator. Lundy lived in the small village of Taginambur near the west coast, at the foot of Mount Kinabalu. The island is now divided among three countries — it is part of Malaysia and Indonesia, and it contains tiny Brunei. Taginambur would become part of Malaysia.

The village was founded by Trevor White, a British missionary who moved there before World War II. He established a Protestant church and a school with around 100 students in grades 1-6 where Lundy and Weeks would teach.

“The children wore the same clothes all week; small children didn’t have shoes,” Lundy wrote in her memoir. She also taught barefoot.

She was given a curriculum to teach, but she also let the children do arts and crafts. She gave them coloring books and taught them how to sew.

In addition, she started a Girl Guides troop — similar to Girl Scouts — for girls ages 12 to 14. “Instead of going camping, we took them into the capital city,” Lundy said. “They had never been in air conditioning.”

She also brought them to the ocean, which they had never seen before. The mountain road was so twisted that the girls and Lundy would get carsick.

The village was surrounded by thick jungle and featured a river that was used to irrigate rice fields. The couple lived in a small home built by the villagers for two single teachers.

It had no electricity — they used kerosene lamps for light in the evening. They made an antenna for their short-wave radio and received news from around the world.

In January, school closed for a rice harvest. The children came back in February, and Lundy had the same group of children for their first grade year.

“Attendance was spotty,” she wrote in her memoir. “Many of them missed school when it rained because they couldn’t get across the river.”

Lundy and her husband began to drift apart during their second year in Borneo. She said she sank into a depression but tried to focus on her students.

In November, the couple were in the capital city of Jesselton, where the Peace Corps office was. A man came out of a storefront and told them Kennedy had been killed. “That was quite upsetting to all of us. That was a hard one,” Lundy said.

“People were upset at the assassination, and somehow our village blamed us and the whole Peace Corps,” she wrote in her memoir. “The missionary, Trevor White, turned against us for a variety of reasons, including the assassination.”

He accused the couple of taking his village from him and said that if they ever returned, they would not be welcome to teach again.

The couple left Borneo six months short of their two-year term. “I returned home a different person,” Lundy wrote. “My experience in the Peace Corps gave me a passion for teaching, which in turn gave me a profession and a way to make a difference.”

Lundy taught children history for decades in middle and high schools around the country, and she eventually remarried.

She and her husband, Arvid Lundy, live in Santa Fe.

In 1987, the couple traveled to Malaysia and went back to the village she had lived in while serving in the Peace Corps. Taginambur was hosting a convention of teachers that day, and one of them approached Lundy and said he knew her.

“He was a student at the school, and he told me where several of my students were,” Lundy said, adding one earned a master’s degree in the U.K. and another earned a master’s degree in the U.S.

“It turned out, 25 years later, these are the kids that were trilingual,” she said.

“They learned Malay, they spoke the Indigenous language Dusun, and then they knew English. So they were primed for good jobs. And that just made me feel vindicated, or happy, or joyful.”

No comments yet.

Add your comment