“Exceptionalism Redux” by Mark Jacobs (Paraguay)

by Mark Jacobs (Paraguay 1978–80)

Evergreen Review

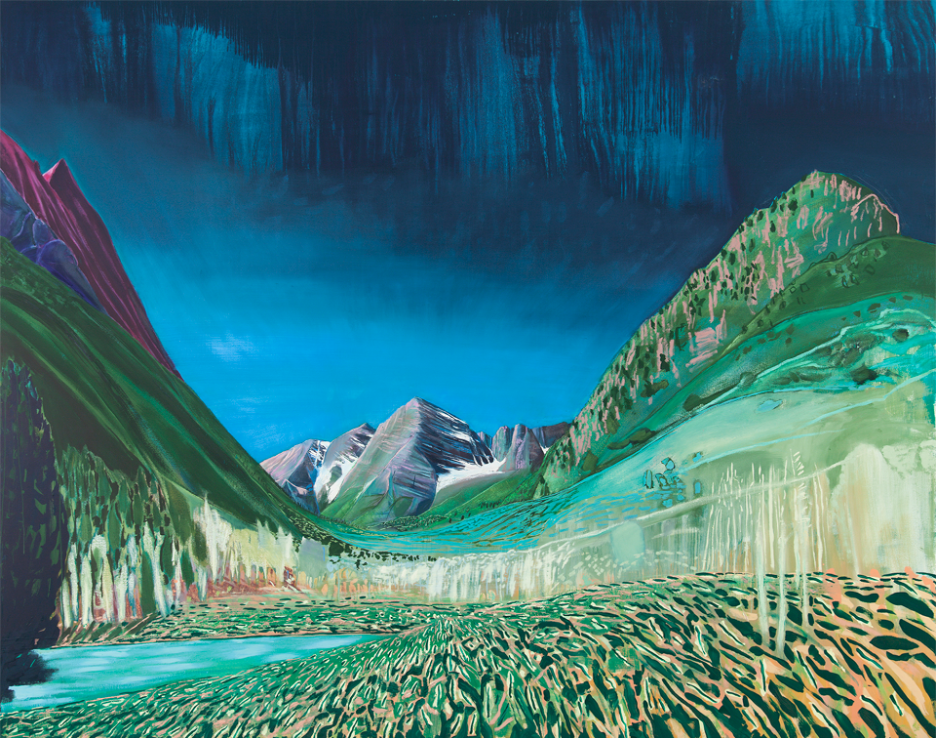

Sue McNally – Maroon Bells, CO (2014)

O, let America be America again —

The land that never has been yet —

And yet must be — the land where every man is free.

— Langston Hughes

from “Let America Be America Again”

In 1990, in the run-up to the first Gulf War, I did a long string of media interviews. I was working as embassy spokesman in Tegucigalpa, and interest in hearing the US case for intervention in Iraq was high. The State Department was regularly sending out updated talking points by cable to be used by people like me. I memorized those points, made them my own in Spanish, then went to the newspapers, the radio, and TV stations ready to be grilled. I was aware, of course, of anti-intervention sentiment in the US and did not dismiss the chants of “No Blood for Oil.” The protests were healthy dissent, as I saw it, part of democracy’s ragged working out.

So what was I doing in Honduras during the bleak and deadly wind-down of the Sandinista-Contra wars? My decision to join the foreign service had something to do with a man named Justo Flor. Justo was a small-time cotton farmer who did everything by hand, from planting to harvesting, an old man by the time we met in a remote village in Paraguay. I was in Potrero Yapepó as a Peace Corps volunteer. Justo had survived a brutal war between his country and Bolivia in the 1930s. The Chaco War, fought in and over a desert, was notable for the hardships undergone by soldiers from both countries, and for not producing a winner. In Yapepó, in one-hundred-degree heat, I sat along the shady side wall of a small adobe house listening to Justo tell me his war stories. The stories fired my imagination, and then fired it again.

The Peace Corps was, for me, an ideal experience. It put me in a position to hear the stories of people like Justo Flor, and the Redes sisters who ran the primary school, and Sixto, a man too restless to hoe cotton. Sixto was always looking for his chance to do something else, something more stimulating, more fun, like organizing a horse race, that would net him the cash he lacked.

Peace Corps was more than stories, though. It seemed to me to represent the best of what America could be in the world. You gave, you got. Even if the wins were small, there were no losers. At a gut-deep level you confirmed that your country could be a force for good. I was not ahistorically naïve. I knew about the Marines in Nicaragua, the CIA in Iran, the Nixon Administration in Chile. I believed those interventions were aberrations, regrettable detours from a road whose destination was a worthy goal.

From Yapepó to the foreign service was a logical next step. Everywhere I lived and worked — in Paraguay, Bolivia, Honduras, Turkey, Spain — stories abounded. In Honduras, as the confrontation with Saddam Hussein intensified to war, I was spending my time with poets, painters, journalists, and political activists opposed not just to US policy in Central America but to their own undemocratic government, which they condemned for its supine collusion with the US. And I was on the receiving end of a kind of education. One week, a Nicaraguan ex-soldier visited me in my office to complain about being abandoned by the American government. The next week he was gunned down on a main drag in downtown Tegucigalpa. Nobody was ever charged in his murder. Bad shit was happening around me all the time.

Also, a few good things. Through my contacts on the left I was able to broker the first-ever meeting between the leader of the Honduran communist party — then outlawed — and the American ambassador. The details stick; they throb in memory: a quiet residential neighborhood on a hill above the city. Early afternoon sun splashed on the flowering bougainvillea draped on high stone walls up and down the street. Two cars approach, park. From one emerges the exiled leader, in Téguz incognito. I get out of the other. We shake hands, and I walk him to a nearby house where the ambassador, who knows how to ask good questions, waits. Over three hours, a life story emerges. He sailed with Castro on the Granma, he tell us, when the revolution took Cuba.

I was happy, spending time with the smartest, most literate, most politically aware people in the country. Their warm acceptance of me suggested that being there, engaging with them, learning (and reciting) their poems, hearing their stories, was a crucial component of American foreign policy. Wrapped up in the work, the life, I did not deeply question the US government’s rationale for invading a country in the Middle East. Despite the enduring legacy of the Vietnam debacle, the official rhetoric about standing up for freedom and the rule of law struck me as plausible.

Why did I accept the George H.W. Bush Administration’s case for war? I think it was because I had not thought critically about American exceptionalism. The foreign service job I did, encapsulated by Edward R. Murrow as “telling America’s story to the world,” depended on a conviction that the United States was unique among nations. From John Winthrop’s exhortation to the Pilgrims to see their American settlement as a “city upon a hill,” through John Kennedy and Ronald Reagan’s latter-day borrowings, America was held up as an example to be emulated, a beacon of light in a benighted world. With all our flaws, we wore the future’s face.

In the Declaration of Independence Thomas Jefferson had enjoined us to show “a decent respect to the opinions of mankind.” How to do that? One answer was to embed a kind of secular evangelizing in US diplomacy. Our mission was not just to explain policy but to provide the context for it, extolling the system that produced it. Our fractious body politic wrestled itself and, more often than not, came up with the right answer. American diplomats promoted both the achieved outcome of our deliberations and the process that led to it. The exercise of soft power, it has been called, but the impulse driving our missionary work was concerned with more than power projection.

I bought it. I joined the US Information Agency, best known for its role in Vietnam, a war that had needed all the explaining it could get. I did the job. Mostly, I liked the job. I liked, above all, connecting with people in cultures not my own. I was less enamored of village life in an embassy or a consulate. Still, I went from posting to posting believing I was doing creditable work that mattered.

Then something changed. When the second Bush Administration launched a second Gulf War, I didn’t buy it. I left active duty as a foreign service officer, although I worked off and on for the State Department’s Office of Inspector General, inspecting American embassies overseas, through the second Obama Administration. (Donald Trump recently fired Steve Linick, who ran the office. Linick, a nonpartisan professional associated with CIGIE, the Council of Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency, was axed for doing his job. News reports suggest he was investigating Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s improper use of staff resources.)

I began paying more attention to understandings of American history that defied the triumphalism implicit in American exceptionalism, like Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of The United States. The process of rethinking I went through, it seems to me, roughly parallels what American society has gone through across recent decades in its reevaluation of the legacy of Christopher Columbus, and our collective past more generally. Today, only the most change-resistant among us continue to celebrate the “discovery” of America as an unambiguous victory for humankind.

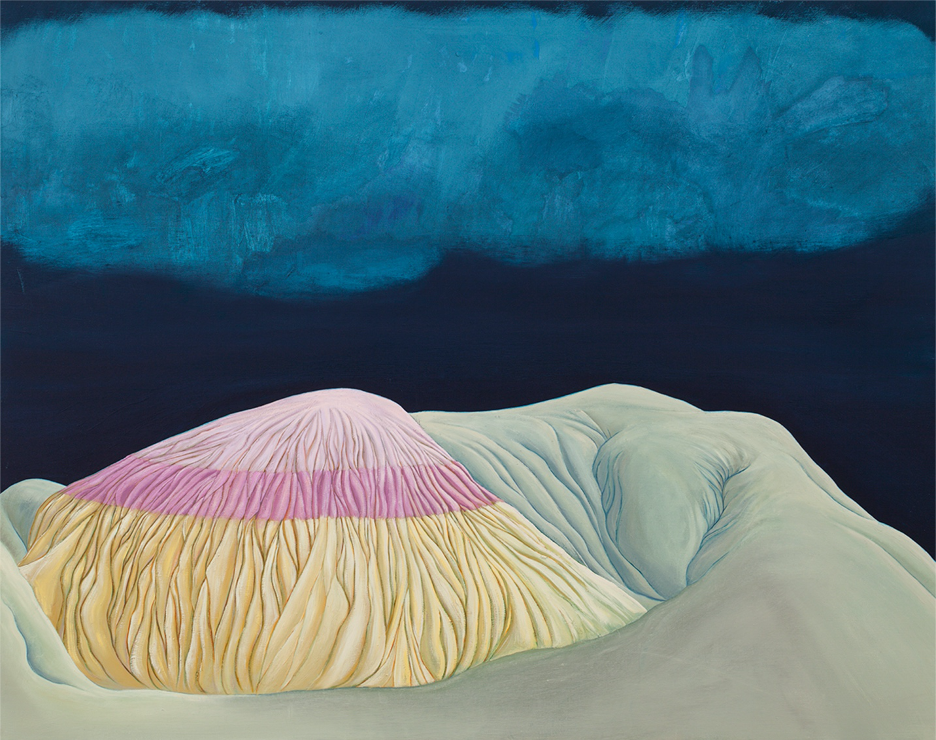

Sue McNally – Yosemite, CA (2013)

We have learned to recognize complexity, and identify the disasters that lurk in unforeseen consequences. Along with Columbus, disease disembarked from the Nina, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria. So did rapine, and unbridled greed, and brotherly hate. Our ambitious and enterprising forefathers came close to exterminating the Native Americans whom they found to be in their way. They enslaved Africans to build the world-class economy that became such an integral part of the American story, our global bragging point decade after decade. They treated the land, and the wealth of the land, as though it were an infinite resource, to be exploited without consequence.

How do we make sense of the intractable contradictions that make up our history? On the one hand, we say; on the other hand. No figure in recent American history better encapsulates the question of American identity — the sexy inescapable core question of who we are — than Barack Obama. On the right side of history. Stunningly gifted. Beautiful. An unconscionably delayed dream come to fruition. And yet, this is the guy whose administration seriously ramped up the deportation of immigrants without papers. Who repeatedly caved to a recalcitrant right wing in the hope, always frustrated, of getting past gridlock. Who dithered on Syria, unable to reconcile the conflicting imperatives of a healthy distaste for intervention and a humane desire to reduce the butchery of the vulnerable. On the one hand; on the other.

The contradictions of American identity did not begin with Obama. They go way back. They keep coming back. And back. Here are a few examples.

Leaving aside his hypocrisy on matters of race, the Thomas Jefferson who wrote to John Adams in 1815 that, “I cannot live without books” — you’ve seen it emblazoned on a tote bag — lived much of his life on borrowed money that he failed to repay. He had just sold his library to Congress, whose own collection had been lost when the British burned the US Capitol the year before. Jefferson thought the Congress needed books to be able to do its work. At the same time, he was chronically short of cash, and the sale helped fill the perpetual hole. He lived well and died beyond his means.

In the 1840s, when Wild Bill Hickock was a boy, his family was involved in the Underground Railroad, helping move enslaved people northward on their journey to freedom. Noble work. One account has Hickock’s father throwing the boy down into the back of a wagon, on top of the enslaved persons he was transporting, when they came under fire. Yet when, as a young man, Hickock announced his intention to marry a half-Indian woman, that same family put so much pressure on him not to, that he gave her up.

In the 1830s, as the Cherokees were driven west along the Trail of Tears, white settlers whom they encountered along the way gouged them financially, selling them coffins for their quickly multiplying dead at inflated prices. Other white settlers put up fences, forcing the Indians to go around their property rather than take a direct route. At the same time, when one Cherokee chief went west to Arkansas along that infamous trail — his name was Major Ridge — he took with him enslaved Africans on whose forced labor he became a prosperous man.

In 1856, in Kansas, on his increasingly messianic crusade to abolish slavery, John Brown and his sons took men holding pro-slavery views into the woods and hacked them to death with swords.

In 1957, before leaning on Arkansas Governor Orville Faubus to withdraw the National Guard he had deployed to block integration of Little Rock Central High School, President Eisenhower privately commiserated with Southern whites facing the prospect of their daughters’ being forced to endure the proximity of black males.

These jarring incongruities cannot surprise us. Like the Paraguayans, and the French, and the Congolese, we have mixed motives. We are constant in our contradictions. Often, we identify the right thing and do its opposite. We ignore the steady breathing of our better angels. Anyway, American democracy has always been messy. For every example of someone living up to our ideals, someone else, sometimes the same person, can be found trashing them.

Still, we continue to hope that history’s long arc does indeed bend toward justice. Jefferson’s rhetoric retains its ability to inspire, his personal flaws notwithstanding. And Eisenhower did the right thing on a matter of enormous consequence, backing Faubus down. His decision in the public realm matters more than the private reservations he felt as a man of his time.

Sue McNally – Crater Lake, OR (2018)

In diplomacy, despite what we knew about ourselves at home, we sought to sell the world a sanitized version of the American story. We were the good guys. Our democracy was a model, our economy a thing of beauty, our society a thriving amalgam of people for whom their acquired identity as Americans subsumed their sense of who they used to be, in another country, another time. I know from experience as a foreign service officer just how that sort of gloating stuck in the craw of thoughtful people in many countries.

Such a simplistic framing may have been strategically sound during the Cold War, when the ideological competition between two starkly different systems of government was fierce. It makes less sense now.

In January, 2017, something very like a virus invaded the American body politic. We’ll keep talking for years about why the organism was so susceptible. Now, Covid-19 has done what the mechanisms of government failed adequately to do. It reveals the operation of the Trump virus in our system, the damage it has done and continues to do. The oft-identified flaws of the man and the jokers in his dirty orbit have been thrown into dazzling relief. Incompetence and venality top the list. On the other hand, and at the same time—here it comes again, the same old action and reaction — hundreds of thousands of Americans go on working and behaving in ways that highlight their professionalism, their self-sacrifice, their awareness of the public good. American history reenacts its fundamental one-act drama.

Sue McNally – Badlands, SD (2014)

The Trump administration has been as inept and deleterious in foreign policy as it has been in combating Covid-19. Where once our diplomats were able to make a nuanced case for considering the US position on global trade, or federalism, or international aviation, those doing the work today must make tactical choices as they step outside the embassy walls: lie by omission, ignore, deflect, obfuscate, change the subject. In the glaring absence of behavior worth emulating, our ability to inspire and persuade evaporates. This is not to say that no good work is being done by the foreign service. Quite the contrary. US diplomats continue to analyze, report, and advocate. They provide vital citizen services. Yet that good work is being done while the Trump virus does its best to further weaken the diplomatic body.

Here’s an example. One of the more rewarding activities I engaged in while on active duty was putting together something we called rule of law programs. We invited American jurists and academics to visit a country whose legal system was shaky. The Americans worked collaboratively with their local hosts, seeking practical ways to improve the functioning of the legal system within the national context, which the Americans typically took pains to comprehend. Similarly, we sent foreign judges, lawyers, and professors of law to meet with their counterparts in the US, working toward the same goal. There were few legal-system-shaking outcomes from these encounters, but small steps were often taken on the road to better.

In today’s international environment, the notion of US professionals flying in to a foreign capital vaunting American expertise in the rule of law is painful to contemplate. Our domestic shortcomings in that area — insert your own favorite example(s) of Trumpian abuse here — open our diplomats, and the rule-of-law specialists who offer their expertise, to a charge of gross hypocrisy. “Do as I say, not as I do,” does not cut it as a rationale for engagement on matters of substance.

Pessimists make the case that the American day is done, and it’s a case we cannot dismiss out of hand. Nations rise, nations fall. On the other hand, maybe the pessimists have neglected to read Langston Hughes with sufficient care, or sufficient imagination. Maybe, too, there is something in this quintessentially American poet that points toward how we can connect with a changed and changing world.

Sue McNally – Bonaventure Cemetery, GA (2014)

The crisis of credibility currently being experienced by the U.S. government will end. When that happens, we will have an opportunity to rethink how we deal with the nations, societies, and peoples of the world. The answer to the question of how does not involve technology. Whatever we do with the internet, or artificial intelligence, or flesh-embedded chips will be of subsidiary importance. The medium is not the message. Technology is an envelope. It’s the content of the letter inside that counts.

What we say matters. So does how we say it. Here’s an example of how well-intended words had an effect the opposite of what the speaker hoped for.

A few years before he died, the great Paraguayan artist Carlos Colombino took me around the Museo del Barro in Asunción. The painter, architect, and preeminent collector of pre-Colombian art had a major hand in putting the museum together, where several of his own pieces were on display. One was a large abstract painting done in his signature xilopintura style depicting Secretary of State Madeleine Albright as a kind of geopolitical grotesque, weirdly reminiscent of Goya’s monsters, as though the two artists had experienced the same appalling dream. He had painted the picture, he told me, in response to Albright’s description of the United States as “the indispensable nation.”

Albright did not seek to offend. Her comment was an exhortation for America to continue to play a central role in world affairs. Implicit in the remark was the assumption that the United States remained a global force for good. But that’s not how Colombino heard the words. Rather, he heard self-righteous hubris, the same old American arrogance como siempre. He heard an insufferable presumption of superiority that made his collaboration with Americans unlikely. That was a shame. Because of his political, cultural, and social influence Colombino was a man whom official Americans would have been well advised to get to know.

So how, when the time comes, when Trump and his cronies sidle off the stage, unrepentant and incapable of shame, do we connect with people outside our borders?

In today’s geopolitical configuration, the notion of a kind of permanent historical dispensation granted to the United States of America is fatuous and, when it comes to diplomacy, self-defeating. Instead, go back to the Hughes poem quoted at the head of this essay. The America for which the poet longs never was, yet it has to be. The formulation is precisely, heartrendingly right. He nailed it. And it seems to me that the poem’s essential aspiration — building a better place to live — is relevant not just to Americans but to anyone. The citizens who will build the America Hughes imagines more than likely have something in common with the people aiming to build their own better places.

If, after Trump, I were headed overseas, tasked with developing a relationship and an understanding with people whom the State Department deemed worth engaging, I’d take along some Langston Hughes. “I’m the one,” he says, “who dreamt our basic dream/in the Old World while still a serf of kings.” Now there’s a starting point for a compelling conversation. I’d ask some questions about the basic dream of the person with whom I was talking. I’d look for points of intersection. I’d look for ways to work together on a project that mattered to both of us. I’d find out who the Langston Hugheses of the country I was serving in were. I’d read them. I’d do some hard listening, and then some more. I would make an exceptional effort.

•

Mark Jacobs has published more than 140 stories in magazines including The Atlantic, Playboy, The Baffler, the Hudson Review, and The Iowa Review. His five books include A Handful of Kings, published by Simon and Shuster, and Stone Cowboy, by Soho Press. He is also a former Foreign Service officer and speaks fluent Spanish and Turkish, along with some Guaraní. Mark’s website can be found at MarkJacobsAuthor.com.

This is the most interesting article I have read in quite some time, many thanks Mark for sharing your thoughts and experiences.

Brilliant. An engrossing, maddening, description of America. A wonderful description of the confusing tangle

of our country’s good and bad instincts and actions. Many thanks.

Dear Mark, An excellent piece in so many regards, but most of all in its honesty and personal self-reflection. Let’s just hope we can crawl out of this one with some bones and tissue left of our democracy. Thank you for writing it.

Heartsick today and groping for perspective, I’m feeling blessed by running across this essay. Thank you, Mark, for writing and persisting. (Nigeria 22)

Thank you, Mark, for this insightful and moving essay in these troubled times.

Also, thanks for the stunning paintings of Sue McNally that accompany the essay..

A profound article that I will continue to contemplate after I leave this page. What continues to astound me is the extensive nature of the damage one man, along with his sycophants, have done. The repairing will take a long time. May diplomats as effective as Mark hang on.

Mark’s essay rings true, for both its positive and negative reflections on what is right and wrong about our country and its foreign policy.. Having worked myself as a Peace Corps Volunteer and Peace Corps staff in Latin America and later as a USAID development professional in many countries, I can attest that the best of us inspires, but the the worst of us is cringe worthy. Now more than ever, reconciling these conflicting truths is a tough row to hoe for those of us who only want the best for our country and for the countries we serve in. Having read this essay, I now feel better that these truths are out in the open and that this will create a more level playing field for discussing how we collectively can improve conditions here and abroad. That is the lesson here.

BTW, I’ve put Mark’s novels at the head of my reading list!