“Ex Africa Semper Aliquid Novi” (West Africa)

Ex Africa Semper Aliquid Novi

Travel with Phillip LeBel (Ethiopia 1965–67)

•

In the July of 1968, I finished spending three and a half years as a secondary school history teacher in Emdeber, Shoa, Ethiopia. Two and a half years were as a Peace Corps Volunteer, while the third was as a contract teacher with the Ethiopian Ministry of Education. Having taught a cohort of students passing through the ninth, tenth, eleventh, and twelfth grades, it was now time to return to the United States. With a graduate fellowship in economics awaiting me in Boston, I took a somewhat meandering trip across Africa, tracing some paths I covered in 1965 while still in the Peace Corps, while others were a journey of exploration. It marked an abiding attachment to Africa that has shaped my professional career ever since.

I had traveled to East Africa during the summer of 1967, flying from Addis Ababa to Nairobi, and then went west to Uganda, and passed into Tanzania through national parks, and capped the journey by climbing Mount Kilimanjaro. While the wildlife in Serengeti and Ngorongoro Crater were exciting to see, I had obtained a visa to visit Rwanda as long as travel logistics and my budget would permit, but travel there that summer looked a bit ominous, given the flood of refugees streaming out of then Congo as years of civil war began to take their toll.

But 1968 would be different.

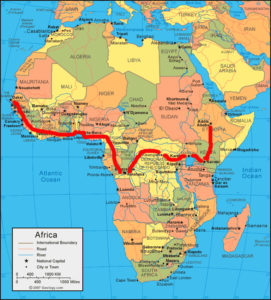

While still in Addis, I managed to obtain visas for Kenya, Uganda, Congo, and Sénégal with the idea that with money saved during my last year in Ethiopia, I could use my air ticket to combine flights with ground travel. And so it was that I flew from Addis to Nairobi to begin my ground travel westward.

My Congo visa was a laisser-passer transit visa granted in late June of 1968. Staff at the Congo embassy said that traveling through by land should not be a problem, as the civil war was over. I was assured that roads were open, and that I could exchange travelers checks at various points along my journey. I would soon learn otherwise.

Flying out of Addis to Nairobi on July 19th, I looked forward to my upcoming journey back to the U.S. Since I had toured in East Africa the summer before, I soon caught a bus that took me westward to Kampala, and then prepared for the westward journey into Congo. After a day in the city, I managed to find a bus that would take me through St. Elisabeth Park to Fort Portal, a small hamlet that served as a watering hole for wildlife travelers and not a whole lot else.

Fort Portal, Uganda

It was in Fort Portal that I learned that there were no regular transit connections into the Congo. The civil war that had erupted in the early 1960s had led to an exodus of Congolese to East Africa, but little in reverse.

After a short stay in Fort Portal, I did manage to find a Somali lorry driver who was bringing fuel from Mombasa to somewhere in the eastern Congo. I managed to get a ride with him and he said that we would stop at the first destination across the border, in the small town of Béni, on the edge of Virunga National Park. Our border crossing was uneventful, and we soon arrived in Béni at a small lodge run by a Greek merchant. I gave the Somali drive some money for the passage, and checked in at the hotel.

Beni, Congo

Main Street, Béni

Béni had the overhang of war. Most streets were deserted, with boarded storefronts showing clear signs of combat having taken place in the area. What little traffic there was on the streets consisted primarily of military vehicles, where armed Congolese soldiers patrolled the streets both day and night. And while I had taken a stroll around town, I had no interest in being stopped by gendarmes, and so spent my next few days at the hotel, looking to find ground transit to Kisangani, where I could take a barge trip down to Kinshasa.

I ate dinner meals in a gazebo just outside the hotel. One evening, the hotel owner and I were chatting away when a lorry driver came by to check in. We got into an extended conversation on travel options as I looked for a way to continue on my way to Kisangani. I asked the driver where he had come from. Like the Somali driver, he had come from East Africa, Mombasa, Kenya, as I recall. I asked him where he was from. He said he had been a soldier in Mussolini’s army, and after the war had left Italy in poor economic straits, and decided to stay on and find work in East Africa.

He did so first in Ethiopia, then moved on down into Somalia and Kenya, where he found work doing the same kind of transit of goods as had my Somali driver. As we continued, I asked him why the East Africa, to which he replied that this was at least one place not dominated by the Americans. Then, as the conversation rolled on, he asked me what was my nationality. When I said that I was a U.S. citizen, he burst into an apologetic frenzy, to which I replied in good humor that I did not expect to come across many Americans in the part of the world either.

After a day or so in which I waited in vain for a passing lorry to take me to my next stop, I asked the hotel owner how could I increase my odds of finding one. He said that about 3 kilometers outside of Béni, there was an intersection of a small road that connected to Goma, and from there onward toward Kisangani. Thanking him for his hospitality, I paid up my lodging and walked, suitcase over head, the three miles to the road. A small shop stood at the intersection, and I negotiated for a small room with the owner while awaiting a passing truck. He made banana beer as a way to gain cash, and we had a few meals of rice and cooked beef with banana beer while we discussed the events of the day, including how it came to be that the region had suffered so much from civil war.

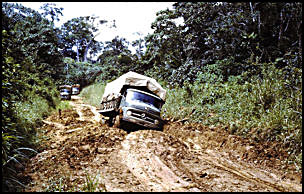

Three-truck-caravan with which I hitched a ride to Kisangani.

Finally, after two days — it now being a total of five since I entered the country — a caravan of three straight Mercedes trucks came by. Stopping briefly, one of the drivers said he could take me as far as Kisangani. I said that I had travelers checks that I hoped to cash to provide him some money for taking me along. He agreed.

He had but an elementary education, and, as we rolled along through the pot-holed, mud road, he conveyed a sense of bitterness over the Belgians. He described how he had had hopes of going beyond his elementary certificate to attend a secondary school, but that he had been refused permission. The tone of his voice showed how many Congolese of the time must have felt. It reminded me of stories I had read that when the Congo became independent in 1960, there were barely a dozen university educated nationals, and that the country was in desperate need of educated individuals competent enough to propel the country forward. Joseph Mobutu, who renamed himself Mobutu Sese Seko as he rose to put down the secessionist rebellion in Congo, had but a secondary school education in a Catholic Christian Brothers boarding school. Patrice Lumumba, who was assassinated in 1961 and whose death helped spark the Congolese civil war, had the equivalent of one-year post-secondary schooling at a government postal office institution. It was little different from other political leaders such as Moise Tshombe and Joseph Kasavubu.

The driver said that there had been a truck overturned on the road ahead in the rain forest, and we would have to spend the night at a pygmy village. Our hosts were gracious in providing us with some smoked monkey meat and rice, though I wound up eating mostly a bit of tuna fish from a can and a baguette while overnighting in the cab of the truck.

First of the three trucks to pull through the mud holes

The next morning, we set out traveling some ten kilometers. The scene before us was nothing less than organized chaos. A straight truck had been nearly turned over on its side in a giant mudhole and was unable to move forward. Both in front and behind the disabled truck were a lines of no less than a dozen trucks, each awaiting their turn to get through the mudhole. The mudhole itself did not have a lot of water at the bottom, as in the tropical heat, evaporation managed to remove most of it in due course.

Apart from the grinding sound of the truck trying to move forward, there were moments of sheer silence in which one could hear sounds of birds and other wildlife no doubt commenting on these strange beasts in their midst. No matter, for we all soon found shovels and rope with which to pry loose the lorry stuck in the mud. And after a few hours, it was our turn to pass through, and so we did with relative ease.

Throughout this passage through the rain forest on the unpaved road, we would pass some village or town that was indicated on my Michelin map that I had bought in Addis, and where from the size of the marker, I had been given the impression that I could exchange travelers checks. This proved to be quite at odds with the assurances I had been given by the Congolese ambassador in Addis, thus raising in me a bit of anxiety as to how I would be able to proceed. But my lorry driver seemed unbothered by my concerns as we passed another night in our lorry, this time at Bafwasende.

Kisangani

The next day, we traveled on a paved stretch of road to reach Kisangani, and I looked to spend the night at a hotel before looking to cash some travelers checks and book my passage on a river barge.

Olympia Hotel in Kisangani

My driver dropped me off at the Hotel Olympia, which had a dance floor and tables where the latest songs were played over a loudspeaker. The hotel owner asked me if I needed a woman for the night, which I politely declined, and I said that in the morning my lorry driver would be stopping by to put me in touch with someone who could exchange my travelers checks.

The next morning, the driver started out toward the Air Congo office, thinking that pilots would be interested in obtaining dollars for travelers checks. It turned out that the Air Congo office had been closed for almost a year. No regular service existed at the time. Then we drove to the home of the president of the Free University of the Congo, where I was left to meet its president Dr. Benjamin Hobgood, and to discuss how I might exchange my checks. He said he thought he could help, but first, after lunch, we would meet the first UN delegation to arrive from Kinshasa at Kisangani in almost four years. With their arrival, I had a first class tour of Kisangani, during which I was given a detailed portrait of the fighting that had taken place in Kisangani. It turned out that not only was the UN delegation the first to arrive east in four years, I was apparently the first traveler to come to Kisangani from the east during the same time period.

We were shown the prison where Simba rebels had held Europeans taken hostage during the fighting over secession of Katanga from the rest of the Congo. Then we saw the Metropolitan Hotel where the hostages had been taken in 1964 as part of a tense negotiation for their release. As we viewed the street leading to the hotel, we were told that the CIA had airlifted in Belgian paratroopers to assist in the release of the hostages. The rebels wanted assurances, and when they sensed that these were not forthcoming, they ordered all the hostages out of the hotel onto the street where from military vehicles the rebels began shooting at will. One of them, Dr. Paul Carlson, a U.S. missionary medical doctor, was killed while trying to jump over the railing of a house along the street. The killing made the front page of an issue of Life Magazine in the summer of 1964, at a time when I was traveling in Europe just prior to entering Peace Corps training to go to Ethiopia. The images stayed with me long afterward.

My temporary host found a solution. He said that he knew of a Greek merchant in Kisangani who would be willing to exchange travelers checks for dollars, and gave me a lift to his office where indeed I was able to make an exchange. After this, we returned to the Hobgood house where I was then given a lift back to the Olympia Hotel. The next morning, my lorry driver stopped by and I gave him some money, along with settling my bill at the hotel. From there, I went on down to the dock to sign up for the next barge heading to Kinshasa.

Congo River barge

The Barge

The ticket officer assumed I would be traveling first class, and I replied that I was only interested in a second-class ticket. After he rolled his eyes a bit, he gave me my ticket. I soon boarded and went to my room, which I would share space with an elderly army officer, then having completed his service tour, was on his way back home outside of Kinshasa.

Life on board the Colonel Ebeya was lively, to say the least. In the evening, a loudspeaker would broadcast the latest Congolese music being played by Franco, while a searchlight would oscillate back and forth to make sure we were not headed into a sandbar. The searchlight often would show the eyes of crocodiles in the river, while passengers bided their time over meals and conversation.

I did not have utensils with me and my roommate lent me his to eat at the common mess benches in the middle of the barge. I have no idea what the first class accommodations were at the more elevated, white painted rear section of the barge. What I did note was the third class passengers slept in the open air under stacks of produce and vehicles, making do with whatever conveniences they could arrange for their temporary stay on board. As to the second class, our cabins gave the impression of some accommodations, even though our food was provided through a common mess hall window.

Passengers on the barge

Along the way I realized that I was the only white person on board the Colonel Ebeya, at least in the second and third class quarters. I was perfectly comfortable with this arrangement, and noted that there were vast quantities of Stanor beer being consumed as we traveled west. In addition, one could have fresh bread baked daily somewhere on board, and canned food such as tuna fish and snails also were available, in addition to whole smoked monkeys for sale. What with the infectious Congolese music, this was an exciting time to be onboard the barge heading westward.

Congo River smoked monkey meat

One evening, I was sitting next to a group of soldiers, no doubt like my roommate, heading back home after military campaigns in the east. We chatted along and soon, one of the soldiers stood up to draw his pistol on me. He said that he was going to kill me just as he had killed so many others during the fighting. I calmly sat at the dining bench and asked whether I could first finish my dinner. As I continued to eat and he began to point his pistol, one of the other soldiers knocked him out and carried him away. They apologized for his behavior and I expressed my thanks for their help.

While onboard the Ebeya, we came across an eastbound barge that had become stuck on a sandbar. The captain announced that we would be bumping into the barge to push it off the bar and that everyone should be attentive. As we approached, some lit baskets in a fit of celebration as if in some kind of a sporting match. The maneuver worked perfectly. The barge was backed off, and we did not get stuck.

Farther on, the captain announced that a good friend of his had died, and that we would be stopping to enable him to pay his respects at the port of Mbandaka, ex-Coquihateville. Our stop lasted several hours, during which time one could see returning soldiers glad to rejoin their loved ones, while goods were off- and on-loaded for the remaining leg of the journey.

Kinshasa

Finally, we arrived in Kinshasa. Customs officers stood at the gangway to examine papers of departing passengers. I presented my passport that had a stamped eight-day laissez-passer visa, but which on arriving was the eleventh day of my trip. The officer took my passport, noting that the visa had expired, and he told me that I was to see the local gendarme office the next day. I then located a nearby hotel, and went immediately to the U.S. embassy to tell them what had happened. They counseled me to remain calm and keep them informed as to when and how my passport would be released.

Although my Ethiopian Airlines ticket had originally included stops in Bujumbura, Burundi, Kinshasa, and then Brazzaville, my overland plan was to cross over the river from Kinshasa to Brazzaville before resuming my travels westward. It turned out that the day I arrived in Kinshasa a coup had taken place across the river that was led by Marion Ngouabi, and for which all borders were being closed. This complicated travel plans a bit, putting aside the momentary concern over how and when I would retrieve my passport from the local Congolese authorities.

The next morning I went to the local gendarme station where I was met by a burly sergeant surrounded by two military officers each with sub-machine guns. The officer began by accusing me of being a mercenary spy. He considered me such as I was the only white person he had heard of in the past four years who had come into the Congo from the eastern border and he was sure that I was either trafficking in weapons, training, or some combination with local rebels, wherever and how many may have still be around. I said that I was a secondary school teacher finishing up three-and-a-half years in Ethiopia, and was on my way home to the U.S. to begin graduate studies. I showed him my plane ticket that included a flight from Brazzaville that was to take me to Libreville, then Lagos, Freetown, Conakry, and Dakar before the transatlantic flight to New York. With suspicion and a somewhat angry tone in his voice, he said I had 48 hours to leave the country, and that I would receive my passport when at the airport.

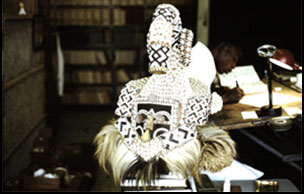

From the Kinshasa Collection

After informing the embassy of my status, I walked around Kinshasa, touring the local market, and visiting the campus of the University of Kinshasa. I managed to visit with a local biology professor who showed me his sculpture collection, and during which time we traded stories about the history of the Congo.

While touring the city, I took my air ticket to the PanAm travel office to see if I could re-route my travel. They booked me on a flight to Lagos for the day I was supposed to leave Kinshasa. On the morning of that day, I checked out of the hotel, took a shuttle bus to the airport, went through customs and security checks, and awaited anxiously for someone to present me with my passport. When boarding began, I came up to the air flight attendant, who upon seeing my ticket, asked me to show my passport. I said that someone had been holding my passport, and that I did not know when I could retrieve it. At that moment, a man stepped forward to present me with my passport, and I was soon off to Lagos on my new flight destination.

Lagos, Nigeria

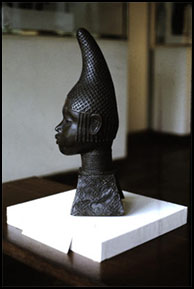

Oba Queen of Benin in the Lagos Museum

Lagos, the capitol of Nigeria at the time, was embroiled in a conflict known as the Biafran civil war. The oil rich eastern region of Nigeria had declared the independent state of Biafra on May 30, 1967 and for the next three years was engaged in a deadly conflict. I had traveled to Nigeria back in 1965 with a group of Peace Corps Volunteers during the summer of that year, and we had visited not just Lagos and Ibadan to the north, but also the eastern part of the country to a village of Ekot Ekpene where a fellow Volunteer had been stationed. Things were now quite different.

Customs at the airport was just beyond aircraft gun emplacements. When I approached an officer, I apologized for not having obtained a visa, but indicated that my ticket showed that my stop in Nigeria was but a way-station along the way back to the U.S. He smiled and said not to worry. He asked me how long did I want to stay. I said three or four days. He immediately gave me a two-week visa, and his only request was that I obey any curfew rulings and that I not travel in the east. The irony in all of this is that I had just traveled overland through a country that was supposedly at peace and treated as a mercenary in comparison to arriving in a country in the midst of a civil war and was treated like a welcome tourist.

After a visit to Ibadan once again, where I was able to purchase a few pieces of sculpture, I returned to Lagos where I caught the next flight heading west on my itinerary. It was a PanAm Boeing 707 “milk run” fight that stopped in Lomé, then Abidjan, then Freetown, then Conakry, and finally Dakar.

View from my room in the Vichy Hotel (now Ganale), Dakar Place de l’Independence

Once in Dakar, after a long flight, I checked into the Vichy Hotel, ironic for its name associated with its loyalty to Maréchal Pétain’s regime during the Second World War, and later renamed the Hôtel Ganalé, on the Rue Amadou Assane Ndoye just off the Place de l’Independence in Dakar. Dakar seemed serene to me at the time, a city full of amenities, including a thriving local market and views along the corniche of the Atlantic Ocean and nearby Gorée Island, once home of the entrepôt slave trade.

At this point, I reflected on how unusual my travel through Africa had been. In just a few days, I was on a PanAm flight to New York where I re-engaged in a country being torn apart by racial rioting and anti-war protests. Soon I was in Boston, deeply immersed in graduate economics, repressing for a while all of the memories accumulated in Ethiopia and travels in Africa that would shape my future career.

•

Phillip LeBel (Ethiopia 1965-67) was stationed in Emdeber for two and a half years, and completed a third year (1967-68) teaching secondary school history under a contract with the Ethiopian Ministry of Education. He has traveled to Ethiopia several times, most recently, teaching a month-long course at Wolkite University in October 2017, and has published articles on Ethiopia in addition to others in his discipline. He is Emeritus Professor of Economics from Montclair State University in Montclair, New Jersey and lives in Delmar, Maryland.

Thanks Phillip, a most engaging picture of Africa in the late 60’s. As a PCV teacher in Dire Dawa (62-64) we had the Somalis attack JigJiga in ’63 but that was a brief scare, nothing like your experiences.

We all had quite an adventure here and there. Thank you for sharing the comment about the Somali attack on JigJiga.

Enjoyed your saga. Three other ex PCs Kenya and I drove across the Congo in 1970 on our way to London. The roads were terrible and ferries problematical, but we made it. We also stayed in the Olympia Hotel in Kisingani. Then we turned north towards the CAR, but not before being detained as mercenaries for a bit. After Congo, the rest of the trip was long and adventurous, but not as dangerous. Bob