Charlie Peters (Peace Corps staff) turns 96!

Charlie Peters, Washington Monthly Founder and First Peace Corps Head of Evaluation, Turns 96

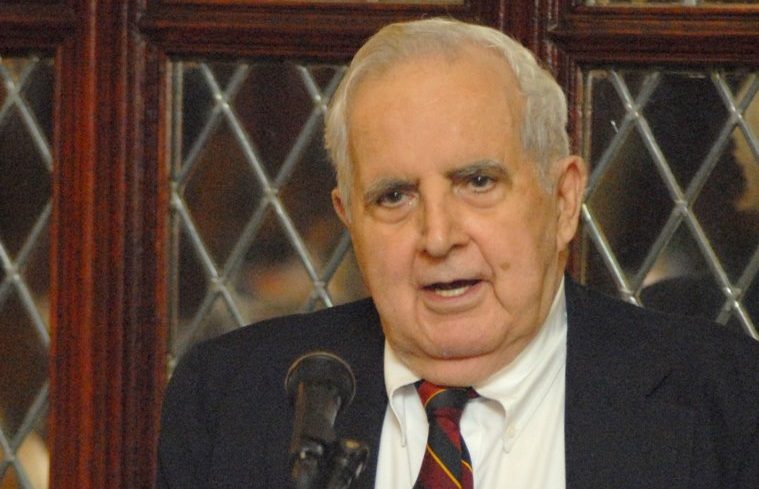

Washington Monthly founding editor Charles Peters in 2008.

Alittle over 20 years ago, I made a short film in honor of Charlie Peters, the founding editor of the Washington Monthly. The American Society of Magazine Editors was inducting my old boss and mentor to its Hall of Fame, a kind of Cooperstown of glossies. Held at a glitzy luncheon at New York’s Waldorf Astoria hotel, the editors of venerable titles lavishly toasted themselves as the National Magazine Awards were handed out. (In retrospect, it had an end-of-an-era feeling, with 9/11 and the collapse of so many publications in the offing.)

My short film was a precis to Charlie getting his Thalberg. It began with shots of the Time-Life Building, the Newsweek building, and the Condé Nast tower, followed by voiceover narration: “… and this is the Washington Monthly.” Cut to rickety stairs in a dilapidated building over a liquor store in D.C.’s Dupont Circle.

Much of the crowd laughed, getting the contrast—and the improbable story of Charlie and the publication he founded in 1969, which has now survived far longer than many of the slick publications being fêted that day.

Charlie was almost 75 when he was hailed in 2001. Today, he deserves an even bigger toast as he turns 96. Please help us celebrate by donating to the Washington Monthly.

For those of us lucky enough to have visited with Charlie at his Washington home, we’ve found him physically slower but still sharp—a remarkable achievement for a man born during the Coolidge administration. When I saw him last, we talked family and Joe Biden. Charlie remembered a moment from my 1997 wedding like it was a month ago. (His lovely wife, Beth, a former ballerina, appears ageless.) Yes, Charlie’s body shows its age, and he doesn’t get out much, but his mind still glows.

Washington Monthly contributing editors Timothy Noah (left) and Michael Kinsley (right) with the magazine’s founding editor, Charlie Peters, in 2019. (Courtesy)

Peters, with the Monthly as his crucible, reshaped the lives of so many young writers, including myself, who would go on to become prominent journalists. They include James Fallows, Jon Meacham, Katherine Boo, Nicholas Lemann, Michelle Cottle, Jonathan Alter, Gregg Easterbrook, Stephanie Mencimer, David Ignatius, Joe Nocera, and Michael Kinsley, another Hall of Fame winner. It wasn’t just that a bevy of smart kids passed through the Washington Monthly, as if it were another ticket to punch between college and The New York Times. It’s that we were transformed. We learned, in Charlie’s phrase, to cover Washington like an anthropologist covers a South Seas island. And not just to cover it with an eye for what’s wrong, but to write about things that work—a task that, especially at the time, most journalists eschewed, fearing that they’d seem opinionated or biased.

I came under Charlie’s spell in the 1980s, when he hired me as an editor, and we worked in those ratty offices I mentioned (and an earlier set we vacated when the rent got too high). My salary was $10,000 a year—around $26,000 in today’s purchasing power, actually just enough to get by in pre-gentrified Washington. I’d fallen in love with the magazine when I was in college at Columbia in New York City. My best friend, Marc, subscribed, and I got hooked reading his copies.

Eventually, I became so enamored that I habitually raced every month to a nearby luncheonette/newsstand on Morningside Heights, which got the issue a bit ahead of Marc’s. I’d lap it up with scrambled eggs and a bialy. It was funny and irreverent, yes, but also softhearted and hardheaded.

Working for Charlie was not, shall we say, easy. In the days before HR departments were everywhere and the phrase “work-life balance” had become a cliché, Charlie rode us hard. Usually, he had two young editors at a time cranking out a monthly publication, a staff far smaller than even other financially strapped opinion magazines. We’d work for two years and then move on. Why endure the low pay and long hours? Charlie was not a masseur of copy (“Let’s move this paragraph here”) or a Rolodex impresario (“Call Senator So-and-So for comment”). He expressed his ideas in his inimical “rain dance,” a kind of sermon, if you will, in which he’d become increasingly animated about a point he was trying to convey to one of us. His corpus of ideas was fondly referred to as “the gospel.”

I remember one article I suggested about how our culture lacked a Charles Dickens, a first-rate writer with a large audience who could evoke sympathy for the poor, something well needed at the time (it was the Reagan era). Charlie immediately got the idea and elevated it. We need someone who not only sparks empathy with the easily lovable, law-abiding Cratchit of A Christmas Carol, he told me. But also with the criminal, decidedly non-saccharine Artful Dodger of Oliver Twist, which is much more challenging but crucial.

Charlie could also be a tough taskmaster. One night after being up for days, I went to his home amid a snowstorm to drop off copy, leaving it in an old-fashioned steel milk box on his stoop. Fearing getting stuck, my cabbie refused to take me back to the marginal neighborhood where I lived. (This sounds like a Dickensian tale, but these were the earliest days of email. And neither the Monthly nor Charlie had a fax machine.) By the time I made it back to my garret, as sunrise approached, Charlie was calling me to tell me how I’d erred in editing a story about Gary Hart. The real scandal, Charlie said, wasn’t the Colorado senator who had been photographed with a young woman aboard the yacht named Monkey Business. The scandal about the presidential frontrunner transfixed the mainstream media. Charlie understood that the real scandal was Hart, whom we liked, cavorting with the Louisiana lobbyist who owned the boat. I can’t remember what subpoint I flubbed. I do remember that I assumed wrongly, but not without reason, given his tone, that I’d been fired.

At 96, Charlie is still a lodestar guiding me. Part of it is political. He has retained his belief, born of experience during and after the Depression, of how government can change lives for the better. As a supporter of John F. Kennedy in the crucial 1960 West Virginia primary and later as the director of evaluation of the Peace Corps, he saw how politics could inspire and how government succeeded and failed.

But much of our admiration stems from Charlie’s personal example, and not just because he was a Negroni man decades before the hipsters. So many idealists come to Washington to do good and stay, as the phrase goes, to “do well”—meaning to enrich themselves. Charlie is a huge exception. He paid himself a pittance and lived on the edge of financial ruin to make this magazine work. When Paul Glastris (also a former editor) took over the Monthly in 2001, he kept Charlie’s lessons and ethos, frugality on everything from higher education—with the magazine’s revolutionary college guides—to its powerful reporting on monopolies. As Paul says, all of us have Charlie’s voice in our head, asking, “Is that good enough?”

•

If you think the Monthly’s brand of solutions-based policy-focused journalism is essential, and if you want to celebrate Charlie’s 96th birthday, there’s something you can do: Make a donation. In fact, do it right now.

As a nonprofit, we cannot do our work without your support. And as a celebration of Charlie Peters, I can’t think of a better gift. Plus, as a token of our gratitude, if you give $50 or more, you’ll receive a free one-year subscription to the print edition of the Washington Monthly.

Great article … brings back some very old memories … the first time I worked in PC/Washington (68-73), in addition to my daily morning read of the Washington Post, I recall fondly my cover-to-cover read of the Washington Monthly from when it was first published in 1979 onward … in addition to making me feel like part of the liberal DC ‘in’ crowd as a very young Washington bureaucrat, it made me think that all of my old poli sci professors would have been so proud of me … just imagine, working in DC and an avid reader of the Washington Monthly … learning by reading and doing. Thanks and happy birthday, Charlie … hope you have many more.

In preparing to celebrate Peace Corps’ 60th anniversary in Thailand, searching through what little memorabilia I have left from those days, I came across Charlie’s name. My eyes lit up and my heart began to flutter as I remembered how wonderful l he was to our Peace Corps group in training in Ann Arbor in 1960. If it hadn’t been for Charlie, I think I would have been deselected. Now there’s a story for your paper!

Rose Marie Welliver Wanchupela

Peace Corps Group 1 Thailand

rosemarie@rose-marie.ac.th