Brian Forde (Nicaragua): Tech can reshape the U.S. Peace Corps and bridge political divides

Brian Forde (Nicaragua 2003-05) co-founded the Digital Currency Initiative at the MIT Media Lab and was formerly a senior advisor at The White House. Today he is co-founded the Digital Currency Initiative at the MIT Media Lab.

•

Earlier this week, President-elect Trump met with some of the top leaders of American tech companies. Some of these leaders are trying to find common ground after being on the receiving end of some of his sharp-worded tweets.

Like many of my friends in the tech community, I’m faced with the reality of a Trump presidency and searching for a way to honor the calls of President Obama and Secretary Clinton for national unity and a chance for the president-elect to lead.

My struggle comes from looking for common ground with a president-elect whose policy goals I largely do not support but recognizing from my time working in the Obama White House just how ineffective obstructionist politics can be for Americans who rely on a functioning federal government.

As we seek to unite a divided country, one unconventional area where we might find common ground, and discover a hidden opportunity for the tech community, is updating a historic government agency — the U.S. Peace Corps.

Surprised? Let me explain . . .

In December 2013, President Barack Obama was preparing to meet with a group of U.S. tech leaders at the White

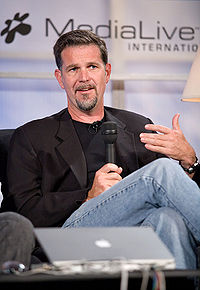

House. I was the senior advisor for mobile and data innovation at the White House, and I asked Reed Hastings (Swaziland 1983-85), the chief executive officer of Netflix — and, like myself, a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer — if he would like to join me for breakfast with the director of Peace Corps, Carrie Hessler-Radelet (Western Samoa (1981–83).

Reed enthusiastically replied, “Yes!”

Carrie and I met with Reed the morning before his meeting with the President, and then I walked him to the West Wing. Reed seemed to relish his discussion with the President, jokingly offering the President a cameo in House of Cards. But I didn’t think much else of Reed’s visit until I saw media reports the following day. To everyone’s amusement, Reed considered the highlight of his day to be his breakfast with the director of the Peace Corps, where they discussed how the agency had been influenced and changed by technology.

Reed’s conversation with Carrie at breakfast that morning sparked two new questions:

- As the length of time a new tech startup goes abroad has been condensed from 4-5 years to 12-18 months — could recently returned Peace Corps volunteers supply the boost Silicon Valley needs to grow businesses successfully and responsibly in the most remote parts of the world?

- Before the end of the next president’s first term, it’s estimated that there will be

Peace Corps’ got Entrepreneurial Talent

Every year more than 3,500 Americans finish their Peace Corps service, mostly in rural areas in more than 60 countries. The Peace Corps has long acted as the last mile of international development, but it could also become the last mile of critical tech training. It has an unrivaled footprint of volunteers canvassing the planet — they are ambassadors of culture, teachers of water-saving agricultural techniques and emerging leaders in their own right. They’re building deep, meaningful relationships with local communities.

Historically, federal agencies, non-profits and non-governmental aid organizations have heavily recruited this rich talent pool of international experience and resilience. One of the many positive side effects of the tech community working closely with the Peace Corps is also tapping into this rich talent pool of Returned Peace Corps Volunteers. These resilient Americans can supply the boost tech companies needs to grow businesses successfully and responsibly in the most remote parts of the world.

As an example, more than thirteen years ago I served as a business and technology volunteer in Nicaragua. Based on the challenges my neighbors and I faced in making calls to the United States, I co-founded a small phone company in 2005. We erected 80-foot internet towers in rural villages to enable Nicaraguans to call the United States and other countries at a tenth of the price charged by established carriers. Eventually our company, Llamadas Heladas, became one of the largest phone companies in Nicaragua.

I am not alone. Other Peace Corps Volunteers have also gone on to start much more successful tech companies,

including Reed — who served as a high school math teacher in Swaziland — and Amy Pressman, who served in Honduras before co-founding her billion-dollar tech startup, Medallia. And it’s not just tech startups, Knight Foundation, with more than two billion dollars in assets to support, among other things, the development of civic tech, is run by Alberto Ibargüen (Colombia 1969-72).

Building a Digital Peace Corps

President-elect Trump should choose a Peace Corps director with technology in his or her DNA. Critically, the next director needs to make technology a priority in every facet of the organization, from staffing and training to the partnerships it builds.

Why? Great, tech-powered, business ideas can come from anywhere. Take Lyft, for example, a billion-dollar Silicon Valley company modeled after the successful ride-pooling in Zimbabwe. Or consider Ushahidi, a popular crowd-mapping tool used during domestic disasters — created in Nairobi.

Facebook powers more than a billion people’s social media identities but the Government of India built the world’s largest biometric identity system for more than 1.2 billion people in a fraction of the time. One of the most successful mobile money companies, M-pesa, was not founded in America, but in Kenya. Analog versions of Deliveroo, Postmates and Munchery were implemented decades ago in countries such as India and Nicaragua.

Ultimately, by bringing the Peace Corps into the 21st century, we can empower communities across the globe to take advantage of emerging technologies that can positively impact their lives.

Peace Corps Director Hessler-Radelet has made dramatic improvements at the agency, including significant structural changes that make it easier to apply to serve as a volunteer — reducing the application process from several days to less than an hour. The Peace Corps has also expanded its digital footprint and improved its outreach, recruiting and marketing, resulting in a 100 percent increase in applications over the last two years.

The agency’s Director of Innovation, Patrick Choquette, has formed strategic partnerships with software firms, such as Duolingo, a language training software company. The Peace Corps has also been leveraging local knowledge to crowdsource invaluable geographic information that can be incredibly helpful in the wake of disasters.

Building on these successes, the next director has the opportunity to make the Peace Corps an important player in spreading the benefits of emerging technologies — enabling this historic agency to have as much impact in the 21st century as it had in the 20th. The wave of technology change is only growing. Whether it lifts or further isolates many parts of the world is being decided now.

The next Peace Corps director could help shape this future in the following ways:

Staff Up

- Establish a Tech Corps – Similar to the Obama Administration’s recruitment of tech talent after the Healthcare.gov meltdown, the Peace Corps should recruit 80 technical volunteers — 10 for each region of the world where volunteers serve — building open-source tools other regional volunteers can leverage.

- Launch Open Source Software Competition – The Peace Corps should host an annual contest to identify the Top 10 open-source projects, built by members of the Tech Corps, and give winners financial and developer support to deploy their tools worldwide.

- Partner with USAID and Local NGOs – The United States Agency for International Development is building technical solutions — from mobile money to blockchain — that will need practical and technical assistance on the ground. Tech Corps and other volunteers could help train locals to run and maintain the technology being implemented.

Train Up

- Expand TechHire globally – My last assignment at the White House was creating TechHire, which brings together businesses, coding boot camps and local governments to help those without a college degree learn to code and fill more than half a million vacant tech jobs. The Peace Corps, in collaboration with USAID, could expand TechHire globally — supporting the development of coding boot camps around the world.

- Build makerspaces – Work with local organizations to establish and build out makerspaces to teach locals about invaluable technologies such as 3-D printing, robotics and solar power.

- Put artisans online – Teach local artisans how to sell their goods on sites such as Etsy, eBay and Shopify, or show them how to successfully crowd-fund to acquire working capital needed for business growth.

Partner Up

- Form partnerships with S. tech companies – Many of these tech companies have not only developed some of the world’s most innovative software and hardware but have also expressed lofty goals to make a difference in the world. The Peace Corps should work with companies like Twilio or telecoms, for example, to donate text messages for use by local healthcare clinics and others, similar to ChatSalud.

- Launch E-book Drives – Partner with Amazon, Kobo and other major e-book merchants to allow consumers to donate e-books to students abroad exploiting the proliferation of smartphones that have dramatically lowered barriers to accessing e-book content.

- Establish a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer Innovation Fund – The top social entrepreneurs and accelerator programs — such as Echoing Green, Knight Foundation, Omidyar Network and Skoll Foundation, among many others — could host an annual event to review applications to fund the best ideas from volunteers on the verge of returning, giving them a path to stay in their local countries to make even greater impacts.

Finding common ground with someone whose policy goals you may strongly disagree with is incredibly challenging. But this isn’t about any one of us or the president-elect. This is about coming together as Americans, with the Peace Corps and the National Peace Corps Association, to help evenly distribute our future to the people who need it most — the communities Peace Corps Volunteers are uniquely trained to serve.

This post was written in my personal capacity and does not reflect the views of MIT or my colleagues.

•

This is just a starter list for ways Peace Corps Volunteers could leverage the latest tech tools to help the people serve throughout the world. Feel free to share additional ideas: brian@forde.com

A truly exciting and ambitious vision on how RPCV’s could help roll out a plan to make PCV’s true agents of technological changes world wide which would help those we seek to serve. I was impressed with Brian’s vision when I interviewed him in January of last year as part of a campaign fundraising study for the NPCA but he’s obviously developed a clear plan to move forward. Now the challenge is to develop the plan to implement and finance the vision mobilizing the considerable talent and venture capital available in the RPCV community.

You have been had!!!!

The Peace Corps value system is built on sacrifice.