Books that bred [and explain] the Peace Corps

By John Coyne (Ethiopia 1962-64)

•

During the 1950s, two social and political impulses swept across the United States. One impulse that characterized the decade was detailed in two best-selling books of the times, the 1955 novel by Sloan Wilson, The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, and the non-fiction The Organization Man, written by William H. Whyte and published in 1956. These books looked at the “American way of life” and how men got ahead on the job and in society. Both are bleak looks at the mores of the corporate world.

These books were underscored by Ayn Rand’s philosophy as articulated in such novels as Atlas Shrugged, published in 1957. Every man, philosophized Rand, was an end in himself. He must work for rational self-interest, neither sacrificing himself to others nor sacrificing others to himself.

Then in 1958 came a second impulse first expressed in the novel The Ugly American by William Lederer and Eugene J. Burdick. This book went through fifty-five printings in two years and was a direct motivation, as Elizabeth Cobbs Hoffman points out in her vivid and important history of the Peace Corps, All You Need Is Love, in establishing the Peace Corps.

Then in 1958 came a second impulse first expressed in the novel The Ugly American by William Lederer and Eugene J. Burdick. This book went through fifty-five printings in two years and was a direct motivation, as Elizabeth Cobbs Hoffman points out in her vivid and important history of the Peace Corps, All You Need Is Love, in establishing the Peace Corps.

The book’s protagonist is, Homer Atkins, a skilled technician committed to helping developing societies at a “grassroots level” by building water pumps, digging roads, and building bridges. He is called the “ugly” American only because of his grotesque physical appearance. Atkins — played by Marlon Brando in the movie of the same name — lives and works with the local people in Southeast Asia and, by the end of the novel, is beloved and admired by them.

Attracted to the ideas expressed in the novel, Senator John F. Kennedy, by January 1959, had sent The Ugly American to every member of the U.S. Senate, and the ideas expressed in it, i.e., our inadequate efforts in foreign aid, would be used by Ted Sorensen when he crafted the speech presidential candidate Kennedy gave on November 2, 1960, at the Cow Palace Auditorium in San Francisco six days before the election.

In this final campaign speech Kennedy called for the establishment of a Peace Corps: “I therefore propose that our inadequate efforts in this area [foreign aid] be supplemented by a Peace Corps of talented young men willing and able to serve their country . . ..”

Many of the young people coming of age in the 1960s, the so-called Silent Generation, rejected “the American way of life” as described by Sloan Wilson, William H. Whyte and Ayn Rand and saw in Kennedy’s challenge a chance to do something for their country.

Since the Peace Corps was established on March 1, 1961, over 280,000 volunteers have served in more than one hundred and thirty countries. More than 1,000 of these volunteers have published books, and more than 650 of those books have focused on their Peace Corps experience.

The first book to draw on the Peace Corps experience was Arnold Zeitlin‘s To the Peace Corps, With Love (1965) that detailed a year of his life in Ghana with the first Peace Corps Volunteers to serve overseas. Zeitlin, an AP reporter, would have a long career as a journalist in the United States and overseas.

Zeitlin’s book would be followed by An African Season, written by Leonard Levitt. The book covers Levitt’s first year of living and teaching in a rural upper-primary school in Tanzania in 1964-65 and was published by Simon & Schuster in 1967.

Zeitlin’s book would be followed by An African Season, written by Leonard Levitt. The book covers Levitt’s first year of living and teaching in a rural upper-primary school in Tanzania in 1964-65 and was published by Simon & Schuster in 1967.

Paul Theroux, a Volunteer in Malawi from 1963 to 1965, has used his Peace Corps experience in such novels as Girls At Play (1969), My Secret History (1989), My Other Life (1996), and The Lower River (2012), as well as in many short stories and travel pieces.

Three illuminating non-fiction accounts of what is means to be a Peace Corps Volunteer come from three different decades, and three different continents.

In 1969, Moritz Thomsen published Living Poor: A Peace Corps Chronicle of his life as a Peace Corps farmer in Ecuador; Michael Tidwell’s The Ponds of Kalambayi: An African Sojourn is a passionately account of his time as a fish extension worker in Zaire in the nineteen seventies; and in 2001, Peter Hessler published River Town: Two Years on the Yangtze, of his two-years teaching English at the Fuling Teachers College.

In 1969, Moritz Thomsen published Living Poor: A Peace Corps Chronicle of his life as a Peace Corps farmer in Ecuador; Michael Tidwell’s The Ponds of Kalambayi: An African Sojourn is a passionately account of his time as a fish extension worker in Zaire in the nineteen seventies; and in 2001, Peter Hessler published River Town: Two Years on the Yangtze, of his two-years teaching English at the Fuling Teachers College.

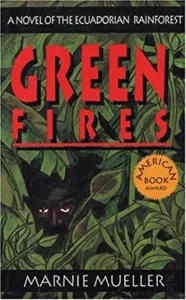

The first commercial “Peace Corps novel” by a PCV is Lament for a Silver-Eyed Woman by Mary-Ann Tirone Smith. In 1991 Richard Wiley published Festival for Three Thousand Maidens, a novel set in Korea, Wiley’s country of assignment. Leaving Losapas by Roland Merullo, also published in 1991, is about the life of a Volunteer in Micronesia where Merullo served. Marnie Mueller’s first novel, Green Fires: Assault on Eden, A Novel of the Ecuadorian Rain-Forest, published in 1994, is about a PCV who returns to Ecuador with her new husband.

The first commercial “Peace Corps novel” by a PCV is Lament for a Silver-Eyed Woman by Mary-Ann Tirone Smith. In 1991 Richard Wiley published Festival for Three Thousand Maidens, a novel set in Korea, Wiley’s country of assignment. Leaving Losapas by Roland Merullo, also published in 1991, is about the life of a Volunteer in Micronesia where Merullo served. Marnie Mueller’s first novel, Green Fires: Assault on Eden, A Novel of the Ecuadorian Rain-Forest, published in 1994, is about a PCV who returns to Ecuador with her new husband.

Using their experience as the raw material for their creative writing, these Peace Corps Volunteers have found that living so intensely in another country and culture has had a profound influence on how they wrote and what they wrote.

Richard Wiley recalls from living in Korea. “As I started to learn Korean I began to see that language skewed actual reality around, and as I got better at it I began to understand that it was possible to see everything differently. Reality is a product of language and culture, that’s what I learned”

The experience is also intensely educational. Novelist Maria Thomas said of her time in Ethiopia, “it was a great period of discovery. There was the discovery of an ancient world, an ancient culture, in which culture is so deep in people that it becomes a richness.”

Bob Shacochis, author of collection of stories, Easy in the Islands, that won the 1985 National Book Award, characterizes this modern generation of expatriate writers as, “torchbearers of a vital tradition, that of shedding light in the mythical heart of darkness. We are descendants of Joseph Conrad, Mark Twain, George Orwell, Graham Greene, Somerset Maugham, Ernest Hemingway, and scores of other men and women, expatriates and travel writers and wanderers, who have enriched our domestic literature with the spices of Cathay, who have tried to communicate the ‘exotic’ as a relative, rather than an absolute, quality of humanity.”

Bob Shacochis, author of collection of stories, Easy in the Islands, that won the 1985 National Book Award, characterizes this modern generation of expatriate writers as, “torchbearers of a vital tradition, that of shedding light in the mythical heart of darkness. We are descendants of Joseph Conrad, Mark Twain, George Orwell, Graham Greene, Somerset Maugham, Ernest Hemingway, and scores of other men and women, expatriates and travel writers and wanderers, who have enriched our domestic literature with the spices of Cathay, who have tried to communicate the ‘exotic’ as a relative, rather than an absolute, quality of humanity.”

Today, the Peace Corps is 60 years old. It has successfully fulfilled Kennedy’s wish for Americans to made a difference in the world. What America has also gained through the writings of these volunteers is new understandings of worlds and cultures that most Americans will never see. And by telling their stories, Peace Corps writers have also told the story of how we are perceived in the developing world, a world that has become increasingly more important to all of us here at home.

Thanks for putting so much together in a short and meaningful essay. Keep up the great work.

I believe the books by Dr. Tom Dooley published in the late 1950s, which detailed his medical work while living amongst the people in SE Asia also helped jump start the PC concept he wrote not only of the work but also the insights into the lives of village preppie and the personal satisfaction gained from bringing good change to people’s live

John, you are right about Dooley. He isn’t mentioned, however, as someone who added to the push for a Peace Corps. Many others are, mentioned for introducing this idea of a PCV movement, in Congress and in articles. I met Dooley in 1957-8 when I was an undergraduate at Saint Louis University. He came to speak and I spent an evening with him and other students and faculty.

John—thanks for the note. reading Dooley’s books certainly inspired me to join the PC, his concept of service was well in line with my Catholic training, the example of St. Francis of Assisi and the Catholic tradition of serving others in need. i would have enjoyed meeting Tom Dooley.

I think back to Eleanor Roosevelt and to Louis Lyons of the Nieman foundation at Harvard and WGBY-TV IN 1960-61 and to my Boston Ryan uncles who were Jesuits. And my parents John (Jack) and Ruth (Delehant) Mycue.

Typo alert! ..It should be WGBH-TV then in Cambridge over the Charles Bridge from Boston and on M.I.T. campus over a former roller rink (can’t remember what was on the street floor then in 1960) next to the Kresge auditorium. (My aging eyes even at the height of the afternoon sun!) .

Nice piece. It stirred a desire to go back and revisit some of the very early books, especially the stories by Maria Thomas.

John,

Over the decades, Peace Corps Volunteers may have been small in number, but as you so effectively found, they have had a significant impact on the way Americans view those outside its borders. The professional compilation of their experiences into the public record serves to document that simple and now–historical fact.

John, bringing that fact to a wider audience is a labor of continuous love.

Useful overview. Well done, John !!

Your impressive piece made me think of the book locker I received as a PCV in Honduras in 1967. I devoured every book in it. I recall reading “Catch 22” and laughing so loud that the Honduran family I was living with asked me what I was laughing about. My Spanish and the subject were such that there was no way I could explain what I was laughing about. I have fond memories of that book locker. Looking back, it played a big role in my reading habits over a lifetime.

John my friend. Such a labor of love and affection for what was hatched from a political process back in the days of collaboration. Nicely done as of course would be expected from you!!