Being First: A Memoir of Ghana I — Robert Klein

by Robert Klein (Ghana 1962–63)

Maiatico Mafia

On March 2, 1961, the Peace Corps staff, like determined squatters, took over the offices formerly occupied by the International Cooperative Agency. Shriver took more than desks and offices from ICA. Led by Warren Wiggins, a group of ICA officers had joined Peace Corps staff. Some of the early participants gave descriptions of the chaotic character of the beginning and Shriver’s role as ringmaster.

Harris Wofford, Kennedy’s special assistant on civil rights, as well as an advisor to Shriver on the establishment of the Peace Corps, recalled early discussions on the establishment of the agency, that the Peace Corps not do any projects directly but that they be contracted out to universities and other agencies. “There was not much chance of that with Shriver running an agency. Sargent Shriver clearly tended toward a fast-moving, hard-hitting, core, central organization. He put enormous weight on speed and the more he saw of the complaints about the State Department and AID particularly . . . how long it takes in their pipeline to get anything done; how, in many projects, the time for them has passed by the time the experts and the money arrive — he was determined that in four months we’d be able to produce volunteers to fill jobs that took fourteen months in the old agencies. He just felt that with Kennedy’s backing he could build a corps that would do it.”

Four months was just about right. It was April 24 when Ghana requested Peace Corps teachers. On August 30 Ghana I arrived in Accra.

Ed Bayley, the first Director of Public Information, remembers those days right after Kennedy’s Executive Order: “All hell broke loose, of course. And we really didn’t know what the Peace Corps was at that point . . . . There was a sort of division there between the bureaucrats and the people coming in from outside. And Wiggins and Josephson and Charlie Nelson, a couple more of that bunch, they came over from ICA. And they really thought they knew all about this, and we were a bunch of amateurs.”

To staff the new agency, Sargent Shriver had attracted and recruited two dissimilar groups. One was the “hard-headed,” practical ICA types; the other “soft-headed” visionary politicos, attracted to the Kennedy presidency. They all shared Shriver’s enthusiasm for the Peace Corps but had divergent views of the yet-to-be-defined role of the volunteers. One side felt that the Peace Corps should serve as a catalyst for change in the developing world according to the model described in the book, The Ugly American. The volunteer was to be an exemplar of American entrepreneurial values, live and work in the villages, not the capital, sleeves rolled up, boots muddy, cheek-by-jowl with host country counterparts, agents of change. The other view was less dramatic. It looked too modest, concrete successes in programs that would draw on foreign aid experience but with the enthusiasm and idealism generated by the Peace Corps dynamic.

In these early days of the Peace Corps, both groups were ultimately hostage to the reality that it was the early volunteer recruits, like Ghana I, who would decide what a Peace Corps Volunteer was by actually being one.

Cable Traffic

As reported in Shriver’s memo to the President, there were four potential Peace Corps programs as of late March 1961: Chile, Colombia (in cooperation with CARE); Tanganyika (a modest request from visiting President Nyerere for some road-builders); the Philippines (Warren Wiggins’ favorite as originally proposed in “The Towering Task”).

However, by mid-April, no country agreements had been signed and the enabling legislation was just beginning to work its way through Congress. Ed Bayley remembers: “The Peace Corps was a precarious idea and we felt that it would be much less precarious if it were a living body instead of just an idea. The risky thing was that Congress might resent this, however. The second risk would be that something bad would happen in the first months that would let Congress say, ‘It doesn’t work.’ But against that was the gain of momentum and the feeling that in the first hundred days we did have the power to do things. Shriver was itching to go.”

And go he did.

Accompanied by Bayley, Wofford, and Franklin Williams, Shriver began a quick tour through Africa and Asia in late April. He was a worldwide salesman for a product whose design had not yet been established nor whose production facility had been built. Peace Corps application questionnaires were not available until the end of April and the first Peace Corps Qualification Examination was not given until May 27. However, there were thousands upon thousands of letters of eager interest from potential volunteers that were being sorted through by a thoroughly confused and overworked Washington staff.

But Shriver pressed on. His first stop was to be Accra, Ghana, where he hoped to be able to meet with Kwame Nkrumah, the President of Ghana. On April 18 the U. S. Embassy in Accra had cabled about his visit:

[The Embassy] welcomes the opportunity to discuss PC with Shriver and introduce him to key GOGhana officials. Have requested appointment Nkrumah morning April 24. Reaction GOGhana was unpredictable.Unpredictable, indeed.

Several days later, on April 22, the Ghanaian Times had an editorial headlined, “Peace Corps: Agency of Neo-Colonialism.” A cable to Washington and Shriver quoted the editorial:

As the world told on paper, and as Mr. Sargent Shriver will want us to believe, PC meant offer voluntary aid to so-called needy countries. Under it, USG will send scores of young Yankee graduates to Africa and Latin America as teachers, social, and industrial-technological workers, and the like. We reject all twaddles about its humanitarianism and declare this nothing short of agency of neo-colonialism, instrument for subversion less developed countries into puppet American economic imperialism.

That same day Nkrumah urgently requested a meeting with the U.S. Ambassador, Francis H. Russell. The Ambassador would cable Washington after his meeting:

Nkrumah said he deeply regretted editorial attacking PC. Agreed would be desirable receive Sargent Shriver and hear his explanations PC. Nkrumah commented press often got out ahead of the government and made unauthorized statements. He would be happy to receive Sargent Shriver. Added obviously nobody had to accept Peace Corps if he did not like it and the whole question should be judged on its merits.

This ambivalence about utilizing Peace Corps assistance continued throughout the two years of Ghana I’s service.

Shriver Meets Nkrumah

On April 24 Shriver and Kwame Nkrumah finally did meet face to face.

Ed Bayley jotted down notes of the meeting which would become an interesting snapshot of what was to happen to Ghana I project: “Nkrumah — splendid idea / teaching schools /electric & water engrs & sanitary / Shd be subject to Ghana Govt direction /Need 270 secondary teachers.”

A follow-up cable reported:

On May 1, 1961, Ghana formally requested Peace Corps Volunteers and set two conditions:

- Peace Corps was in Ghana at the invitation of the government and will be responsible to the government of Ghana and take their instructions from its ministers.

- Ghana expects Peace Corps members to accept and carry out operational and executive duties in the field, and not regard themselves in the role of advisers.

Neither Shriver nor Wiggins could have given a better description of how the Peace Corps was going to be different from previous U.S. foreign aid programs.

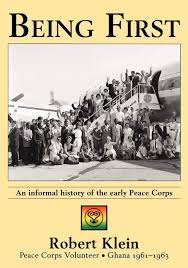

Ghana I prepares to depart

After the discomfort of the selection process at UCal/Berkeley [early Trainees were subject to “deselection” while going through training on U.S. college campuses, usually by psychiatrists and psychologists hired by the Peace Corps or the college], we were glad that training had been shortened by one week, ending on August 21. Next, we were told to report to Washington on Monday, August 28 for a White House event and then to board our Pan Am charter to Accra.

As early as July 23, I was writing home, “Good news—Our training program is being shortened by one week and we are being given leave from August 21 to August 28…. “We are being flown to Ghana by chartered plane from Washington and will be allowed up to 216 pounds of luggage [Why 216?]. We have to report to Washington by 11 AM on August 28. There are rumors of a White House reception.”

I think Peace Corps/Washington was happy to give us a few days at home before flying to Ghana because at the time the Peace Corps legislation was working its way through Congress. Having us in our hometowns could and did generate local news stories such as: “Young Wilmette Man Leaves For Ghana; “Graduate To Teach with Peace Corps in Ghana”; “Miss Vellenga In Ghana, West Africa”; “Plainfield Teacher Chosen for Peace Corps in Ghana.”

We scattered from Berkeley for the brief leave to say goodbye to family and friends (and to buy our weight allowance of 216 pounds of clothing and supplies, trying, for example, to figure out how many handkerchiefs would be needed for two years).

One of the more memorable farewells for Ghana I PCVs happened to Alice O’Grady. Alice had continued through training to perform in San Francisco on weekends with a musical troupe, the Lamplighters, which was presenting Gilbert and Sullivan’s “The Mikado”:

We did a show the night before I left for Chicago, and then onto Washington, D.C., and Ghana. The director, who was also in the cast, at the end of each performance would step forward and say, ‘Thank you for being such a good audience; we would like you to join the cast in the lobby for coffee.’

But that night she said, ‘We’re not able to join you in the lobby because one of our members is going overseas with the Peace Corps and I stepped forward and had my first and only solo bow with that company. Got a nice round of applause.

Then, because the plane was leaving soon, I changed but none of the cast did. They all went to the airport as Japanese schoolgirls, etc. in their costumes.

When they called the plane and I was about to leave, they all went down on one knee and sang ‘Hail Poetry’. It was just beautiful. It’s a lovely kind of hymn, but not from the Mikado. They also presented me with a hobby horse, a horse’s head on a stick, for me to travel to Ghana on. It was a very touching sendoff.

In the Rose Garden

At the same time, the road surveyors of Tanganyika I were completing Phase One of their training in El Paso, and were heading for more training in Puerto Rico. So, in transit between the two sites, they joined Ghana I in Washington to meet Kennedy.

I remember envisioning a White House reception, based on earlier experiences at various Bar Mitzvah and wedding receptions. I expected a high-class lawn party setting with gloved waiters in crisp white vests, circulating among us with canapes and drinks; we’d have an opportunity for casual “cocktail party” chatter with the President, Shriver, maybe even Jackie. I was not alone in such thinking.

Ruth Whitney remembered that White House reception: “Georgianna McGuire and I wore our basic black dresses — now we kid about it all the time — and white gloves. She and I must have grown up with the same kind of mother who taught us what to wear for such occasions.”

The White House setting, remarks by Kennedy, and approximately 75 bright young, newly-minted Peace Corps Volunteers attracted useful press coverage. The reception was a very crowded, stand-up affair on the hottest day of the year in the Rose Garden, with reporters and photographers outnumbering guests.

It must have been a heartwarming sight to those lobbying for passage of the Peace Corps bill. Kennedy appeared with Shriver hovering near him and spoke to all of us. The line that most of us remember is when he said, “So I hope you realize — I know you do — that the future of the Peace Corps really rests with you.”

We were okay with that, thanks to Professors Apter, Drake, and the others at Berkeley.

That the “future of the Peace Corps” really depended on us had been stressed by Shriver earlier in the day when he spoke to us at a State Department “briefing” which seemed designed to reassure the briefers and not especially to inform us.

Shriver told us, “The President is counting on you. It’s up to you to prove that the concepts and ideals of the American Revolution are still alive. Foreigners think we’re fat, dumb and happy over here. They don’t think we’ve got the stuff to make personal sacrifices for our way of life. You must show them. And if you don’t, you’ll be yanked out of the ball game.”

We had faced eerie psychiatrists, seven varieties of psychological testing, chilling stories of boa constrictor attacks, and the perils of partying in Strawberry Canyon above the Berkeley campus (I never knew they made such large bottles of wine.). Shriver could not daunt us. We were ready — to teach, if not to sacrifice.

I must have been mulling over Shriver’s exhortation in the Rose Garden when Tom Wicker of the New York Times interviewed me. In the Times the next day, he wrote: “Robert Klein made it clear that he and his fellow corpsmen had not been trained as political missionaries or assigned to preach particular doctrines. He said that David Apter, a political science professor who headed the four-man faculty for the Ghana group’s two months of training at the University of California, had stressed that each volunteer was going abroad as an ‘individual with his own ideas.’”

Shaking Kennedy’s Hand

After the Rose Garden speech, President Kennedy, in a stage whisper, asked an aide how busy his schedule was because he wanted to greet each of us individually. He retired to the Oval Office and we paraded through single file.

All of us have some memory of that moment. Don Groff recalled: “I remember just being kind of dumbstruck, going through the line. I do remember that I shook Kennedy’s hand and, as I moved on, he said, ‘Ghan-err or Tanganyika?’ And I told him, ‘Ghan-uh.’”

For Nate Gross, it was a storybook experience with this special history: “In 1959 Kennedy came to a convocation at Beloit College. Jackie was with him with her classic A-line dress and pillbox hat. He gave a great talk there. I later got to shake his hand. So I had great feelings toward Kennedy before Peace Corps. It was really wonderful to be at the White House even though in the receiving line the exchange was perfunctory. We didn’t have any conversation. He just said Good Luck and shook my hand. I think some people had a few sentences.”

Newell Flather was the last in the reception line and said to President Kennedy, “I’m from Massachusetts too. And my brother was actually a roommate with your brother [Teddy] in college. Then I said, I just want to say something myself. You’ve been under a lot of criticism, skepticism about Peace Corps. We’re going to serve you well.” (As an aside in our interview in 1997 Newell said to me that he felt the comment was a bit “saccharine.”)

DeeDee Vellenga would write in her diary of that day in the Rose Garden: “The Rose Garden reception was unbelievably hot and confused with reporters, cameramen, wires, tape recorders all over the place. When Kennedy did try to meet us informally after his brief message, he was swamped so it was decided to let us file through his Oval Office and shake hands with him. I couldn’t think of a thing to say to him. All I noticed was his piercing blue eyes. He paused for a moment and looked hard at me and then said, ‘Good luck’— didn’t know quite how to take it. Meeting Shriver was very encouraging — he is down-to-earth and very dynamic in a gutsy sort of way. I think the Peace Corps has a real future if he continues to head it. Now it’s up to us to see how things go in the field!”

Party On

The Washington whirl continued for us that evening with a party at the residence of the Ghanaian Ambassador, Mr. W. Q. Halm. Looking back, it is remembered by all of us as a wonderful, hot, and steamy introduction to Ghanaian hospitality. The Ambassador assured us that it never got as hot and humid in Ghana as it did in Washington D C. We danced, ate, and drank for tomorrow we were, not to die, but to fly into the unknown of Ghana.

After the Embassy party, George Coyne remembers: “Jim Kelly, Maureen Pyne, Ruth Whitney, and myself went to a nightclub and then caught a taxi up to the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception. We wanted to say a prayer because we really didn’t know what we were getting into and we wanted to light a candle. The cathedral was in complete darkness and we had to light matches to find the door but were able to get in.”

It’s reassuring that at least four of the group knew enough not to just curse the darkness but to light a candle. They were ready for whatever Ghana might bring.

Here Today, Ghana Tomorrow

On August 29th the fifty of us went to National Airport to board our Pan Am charter, a four-engine propjet, dubbed The Peace Corps Clipper. Before boarding, there were some technical matters to deal with. Peace Corps wanted to ship all of our luggage with us on the flight, no doubt calculating that, like a security blanket, arriving with our newly purchased towels, sheets, and underwear, would bring us reassuring comfort in our early days in Ghana.

I do not know the payload of the good old Clipper but full fuel tanks and an additional 10,800 pounds of baggage (that’s, 216# x 50) might be a problem. Some seats were removed from the plane and each of us was weighed on the luggage scale. Getting this project off the ground may have been more difficult than we were aware.

Sue Bartholomew remembers vividly the long day: “We waited and waited and waited. Finally, someone came to tell us they were taking seats out of the plane because we had all our luggage and that plane wasn’t going to get off the ground. I thought it was funny. They even had to weigh us; then half the seats were gone. Howard Ballwanz talked to the pilot who told him that there was something called Forest Airline, did a lot of charters. They got that name because with so many people on board they never got higher than the tops of the trees. The pilot said that’s what we’re doing. It’ll take a couple of hours to make our altitude.”

Aboard the Peace Corps Clipper

Pat Kennedy of the Washington staff was our escort officer, not out of fear that any of us would try to escape, but to smooth the way in Ghana by assisting the newly appointed Peace Corps Representative, George Carter, in getting us settled into our assignments. Pat had been involved with the development of the project from the very beginning.

The flight took twenty-three hours, stopping in the Azores and at Dakar, Senegal, before arriving in Accra the next day, August 30, 1961. All of us recall the flight in different ways but we all agree that there were two distinct groups — the singers and the card players.

The singers were people who, at Berkeley, would come together to sing madrigals for relaxation and their own enjoyment. Alice O’Grady, Tom Peterson, Valerie Deuel, Don Groff all had some musical training and sang beautifully. This was definitely not the beer-drinking Rathskeller “Michael-Row-The-Boat-Ashore” crowd.

Twi, Twi

Thanks to the singers, Ghana I was able to rise to the challenge that the Ambassador had mentioned in a cable to Washington just before our departure:

Planning high-level reception PCVs at the airport since this first group arrives abroad. Request most capable spokesman be selected make carefully prepared arrival statement. One other PCV might be interviewed Radio Ghana. Suggest group be prepared to sing traditional Twi song learned Berkeley.

The challenge was that at Berkeley we had learned very little Twi and even fewer Twi songs, but we did have great improvisational skills. Weren’t there twenty-five-plus non-teachers in our group about to take up two-year teaching assignments?

The madrigal group — augmented — came to our rescue and not only learned “Yen Ara Asase Ni,” but sounded good doing it. Someone had had the fortuitous foresight to have copies of both words and music for the song, which is a popular, unofficial anthem. When the time came to sing at the airport after arrival, easily half of us stood in the back, moving our lips while the brave, strong voices of the true singers were being recorded by Radio Ghana. It was an instant hit with the Ghanaian radio audience as much for its novelty as for its excellence of performance. In our first few days of bus touring around Southern Ghana, several people made comments like this (or a close variation thereof): “Oh, you are the group that sang that Twi song. That was fine.”

The Best Hearts and Minds

Back to the flight — the non-singers, that is the Hearts card players, had stormed through the transit lounge at the airport in the Azores during a refueling stop and stocked up on wine and cheese which assured the continuance of the game and the avoidance of sleep. Although, I’m sure most of us catnapped during the flight.

The flight also made a stop in Dakar, Senegal. This first step on the African continent was intoxicating. In the freshness of dawn, the air was warm and caressing, with the sweet fragrance of bougainvillea tantalizing the nose. We were touching the soil of Africa!

We were giddy with anticipation and lack of sleep. I remember clumsily dancing around with frangipani flowers stuck behind each ear.

Nate Gross remembered, “Somewhere between Senegal and Ghana we were flying low enough to see the ground and some villages and huts and stuff. That’s when I thought, ‘Holy shoot, we’re really going to Africa. Can I handle this? What’s it really going to be like when we hit the ground?’”

When we landed in Accra, Ken Baer, an imposing figure and probably one of the few in the group comfortable wearing a seersucker suit served as our solemn spokesman. Paraphrasing Shriver’s remarks on his visit to Nkrumah in late April, Ken said, “We have come to Ghana to learn, to teach, to try to further the cause of world peace but above all, to serve Ghana now.”

We sang (some of us did, anyway) and then boarded buses to be taken out to the University of Ghana at Legon where we would have further training and orientation organized by the Ministry of Education.

A lot had happened in the six busy months following President Kennedy’s Executive Order. The Peace Corps was now a reality.

Rite of passage

If there was any rite of passage hinted at by the experienced African hands at Berkeley, it was to dance the High Life at the Lido nightclub in Accra. To do so would mean that you were becoming a participant in the “real” Ghana.

The very first night after our arrival many of us did just that — dancers, non-dancers, drinkers, non-drinkers, the shy and the bold, those in culture shock, and those too dazed from the journey to be shocked by anything. Valerie Deuel described that first night in Ghana at the Lido: “Sitting in a circle around the dance floor, everyone ordered beer; it was very hot, not air-conditioned, with an open roof, sweaty. People getting up and doing the High Life. Being shy and having a block against dancing all my life, I got up and did the High Life anyway. I think I felt it was required of me, so I danced. Back home I never even did the Twist but I was swept up by the feeling of that whole evening.”

Our exuberance and joy at being there was capped by Laura Damon and John McGinn winning second place in a High Life contest, dancing an awkward but wildly enthusiastic combination of Jitterbug and the Twist with just a hint o Ghanaian High Life. The whole evening made me begin to feel myself a part of Ghana. Sub-rites of passage followed — finding and then negotiating the fare for the taxi to drive us back out to the University and, in looking for our dormitory on the dimly lit campus, stumbling into an open storm drain.

Happy Days

Soon after our arrival, a columnist, identified only as “Rambler,” wrote in the political party newspaper, the Evening News: “You are welcome to Ghana, which, I understand, you have come to serve as teachers. I like the way you sang that Ghanaian hit on your arrival at the airport two days ago. Let that song make you non-aligned during your stay here, for though you came at our own invitation, you will terribly harm Ghana-American relations if you do not get yourselves acclimatized [sic] to the national climate of Africa. I wish you patient, understanding hearts — and a happy stay.’

We might not have thought of ourselves as “political missionaries” as I had said at the Rose Garden, but others might be seeing us in a different light.

And all in all, and for most of us, our days in Ghana were a “happy stay.”

•

Robert Klein retired in 1994 after careers as a teacher and a supervisor in special education and moved to Tucson. The founder of the RPCV Oral History Archival Project, he passed away on April 4, 2012, at the age of 83, after complications arising from the implantation of a pacemaker.

Robert Klein retired in 1994 after careers as a teacher and a supervisor in special education and moved to Tucson. The founder of the RPCV Oral History Archival Project, he passed away on April 4, 2012, at the age of 83, after complications arising from the implantation of a pacemaker.

For his last 3 years he had been involved in developing the RPCV Archival Project in cooperation with the Kennedy Library.

Robert, thank you for sharing and have a happy stay – you’ve earned it,

Robert,

I greatly appreciated your accounting of Peace Corps’ sending its first Volunteers to Ghana. JFK was correct when he stated to your group at the White House reception: “the future of the Peace Corps rests with you”. And–indeed it did for your group “lit the candle in the darkness”, allowing thousands of future Volunteers to have a once in a life time opportunity of service to others.

By this accounting, you remain with us.

Sincerely,

Jeremiah Norris

Colombia VI

I was a 10-year-old living in Ghana with Embassy parents when we went to the airport, with a lot of other Embassy staff, to welcome you there. 12 years later, so inspired by you, I became a volunteer in Zaire (”73 to ’75). Thank you for recording this piece of primary history.

Tina Thuermer

John

Today’s edition of your Worldwide site is a very valuable collection of Peace Corps history. I’m sure that all PC veterans appreciate it. It should be bound together in a small book to make it more easily available. Keep up the good work. Don’t quit! Neil

I like Bob Klein’s book BEING FIRST. Cogent, kind, delightful.