“An Unexpected Love Story — The Women of Bati”

by John Coyne (Ethiopia 1962-64)

If the reader prefers, this may be regarded as fiction. But there is always the chance that such a piece of fiction may throw some light on what has been written as fact. — Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

•

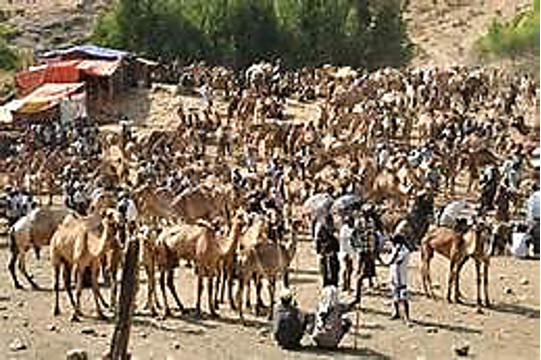

AT AN ELEVATION OF 4,000 FEET, the town of Bati, Ethiopia, off the Dessie Road, is the last highland location before the Danakil Depression. A hard day’s drive from the Red Sea, it’s famous only for its Monday market days when the Afar women of the Danakil walk up the “Great Escarpment” to trade with the Oromos on the plateau.

These women arrive late on Sunday, and with their camels and tents, they cover the grassy knob above the town. They trade early in the next morning for grain, cloth, livestock, and tinsels and trinkets imported from Addis Ababa, 277 kilometers to the south.

These women arrive late on Sunday, and with their camels and tents, they cover the grassy knob above the town. They trade early in the next morning for grain, cloth, livestock, and tinsels and trinkets imported from Addis Ababa, 277 kilometers to the south.

Numbering as many as fifty, the Afar women are young, tall, strong and statuesque, and in full command of their livestock as they herd cows and sheep onto the grassland slopes that border the outdoor market.

The men of the Danakil do not come up out of the desert to the plateau. They do not relate to highlanders and in previous generations were notorious for the male code of achieving manhood by castrating a rival. Proof that they were worthy of marriage.

In the mid-sixties when I lived in Ethiopia and worked for the Peace Corps as an associate director, I would arrange my trips to visit Volunteers to be able to visit the Monday market, and in the late afternoon, and also having Italian food on the open veranda overlooking the road into the desert. From there, I’d watch the women leave Bati.

Coming off the hill, these Danakil women gathered their camels and goats into formations, hitting full stride by the edge of town, beginning a journey that would take them to their villages deep in the desert.

The people of Bati saw nothing thrilling in these desert women; there were too many taboos between them. But for myself, a stranger, watching the string of young Afar women leaving town in such dramatic fashion was an unexpected glimpse of rare beauty.

BESIDES THE MARKET, there is little to recommend Bati, which stretches in a narrow strip for a mile on both sides of a two-lane tarmac road. The town begins and ends in the bush. There is one motel — a good one by provincial standards — outside of town and near a small Northern Ireland Protestant mission.

The government’s elementary school is at the other end of town. It was to this one-story building, constructed by the Italian army as a military outpost when they occupied Ethiopia during the Second World War, when a Volunteer was first assigned in the fall of 1966.

Nothing much was heard from the Bati Volunteer that first year. He wasn’t a problem, so the Peace Corps staff never noticed him.

Ted was from North Dakota, the son of a minister. He was shy and scarred — his face deeply pocked — the result of a disease in early childhood. Ducking his head or gazing off, he would rarely return anyone’s look. In a group, he’d shuffle a step or two to the side, turning himself into a physical outcast.

Still, other Volunteers saw a streak of brilliance in him that ran counter to his oddness, and among them, he found friends and respect.

AT THE START OF THE NEW SCHOOL YEAR, the Peace Corps Country Director assigned me to be the APCD for Volunteers on the Dessie and Gondar Roads. There were more than a hundred of them in the twenty towns and villages that stretched over a thousand miles on two gravel highways that dissected the escarpment.

In early October, before I departed for a series of visits that would take me nearly a month, I wrote each Volunteer on my route to say I was on my way.

My arrival in a provincial village was always a special event for the Volunteers, an excuse for them to make popcorn in a pan over an open fire, an opportunity to hear the gossip from Addis Ababa, and if the town had a restaurant, a chance for dinner of injera and wat or Italian food and Melotti beers. They knew I was buying.

Traveling the road was like political campaigning. I had to get myself up for the Volunteers, and the people at each location had their own set of issues and problems. One constant: Volunteers along the roads were cut off from the outside world. Isolated from friends and family and the familiar, handicapped by the language and customs of a foreign world, Volunteers often withdrew into themselves and became guarded.

Occasionally, I’d come to a town only to find the Volunteers enraged over a seemingly minor incident — a verbal disagreement with the local headmaster, a flare up between roommates that had festered and swelled into something more. The grievances they expressed, I learned, often stood in for something else, something that was beyond my power to address. But I was reachable and responsible. When I showed up, they could hurl their accusations and have the satisfaction of their fury.

BY THE TIME I REACHED BATI I had visited a half dozen towns and I needed a break, which meant a brief stay at the Bati Motel. Situated on a rise above the main road before the town itself, the motel was hidden in a cluster of small hills. Someone, however, had thought enough of the spot to plant a roadside hedge and garden of exotic plants that had flourished at the edge of the desert.

Any traveler coming from the nearby town of Kombolcha, as I was, would drop down a few thousand feet in a series of quick turns, mostly following a dry river bed. After a long stretch of brown, hard land, there was one last turn and the traveler would burst upon a rich, cultivated valley of blossoming passion flowers and bougainvillea bushes. The sight would make one remember the dryness in his or her throat, and the most natural thing in the world was to steer up the incline and into the motel yard.

The motel had only a few simple rooms, each with an inside toilet. Another building housed the restaurant and bar. There was also the veranda with a cool tile floor, and always a light, refreshing breeze.

Once past the flowers, the motel — full of garish plastic furnishings — had no charm. Yet there were tablecloths, reasonable food, cold drinks, and, with few travelers — mainly government officials and a handful of European tourists — I often had the terrace pleasantly to myself.

Over lunch, gazing out at the empty landscape across the road, I’d watch huge, prehistoric secretary birds search for food. Native to sub-Saharan Africa, they have long necks and legs and are capable of flying only a few yards. Each time they rise on ungainly, wide, flapping wings, they quickly drop again to the ground and, stumbling forward, rip at the ground until they seize a lengthy lizard with a crunch.

Over lunch, gazing out at the empty landscape across the road, I’d watch huge, prehistoric secretary birds search for food. Native to sub-Saharan Africa, they have long necks and legs and are capable of flying only a few yards. Each time they rise on ungainly, wide, flapping wings, they quickly drop again to the ground and, stumbling forward, rip at the ground until they seize a lengthy lizard with a crunch.

AFTER THE MIDDAY HEAT, I climbed back into the Land Rover and drove the last mile into town to find Ted and see how he was doing.

His house, on the edge of the school’s compound, had also been built by the Italians, with thick stone walls, large windows, and a wide, wooden veranda.

As I parked the Land Rover at the doorstep, Ted appeared in the doorway, unshaven and unkempt. He had lost weight since I had last seen him in the capital, and he was wearing a tee shirt, faded jeans, and a pair of the cheap, plastic brown sandals sold in the market.

Shaking hands, he mumbled hello and backed off, gesturing for me to follow him into his house.

He was not alone.

Across the room and near the rear door of the house was an older woman cleaning the windows with rags and a pail of water. With her was a girl of perhaps fourteen, wearing a sparkling pink dress that had been designed in a Western style, made in China, imported to Ethiopia and locally sold. Both women gave me a cursory glance. I nodded respectfully and they bowed back.

I had brought Ted a packet of mail — letters from home, Peace Corps memoranda, the New York Times Week In Review, Newsweek, schedules of physical examinations — all sealed in a large, brown government envelope with BATI written in thick letters on the outside. I handed it over, expecting Ted to be excited, but he set the package aside and asked if I would like a cup of tea.

I nodded okay and he spoke a few quick words in Amharic to the older woman, who then left the windows and went to the kitchen. The young girl did not move from the doorway.

As it was Monday I was thinking of the Danakil women, wondering if they were still at the hillside market. I walked to the rear of the house and looked out the door across the open field to where they were encamped. As I approached, the girl moved quickly away.

I greeted her in Amharic and smiled, but though she whispered a reply she kept her face turned away, as is the custom of Ethiopian women. I asked her name and if she went to school. Her voice was too soft for me to hear her replies.

Ethiopians never speak loudly. I’ve gone into crowded offices in Addis Ababa and found people talking to each other across the room, never raising their voices about a murmur. I bent closer and again asked her name.

“Ayana,” she repeated, still not looking at me.

She was not beautiful. There are many remarkable-looking Oromo women, but Ayana’s slightly brown face was round and chubby, unlike the thin eloquent sculptured profiles of most Ethiopian women. If she were a student, I guessed she would have been in the sixth or seventh grade.

Ted came over then and asked, “You’ve met my wife?” He was smiling, and as Volunteers are known for putting on staff, I went along with it.

“Yes,” I said, nodding politely at Ayana. The girl, I assumed, did not understand English.

I walked back across the living room to the front door and, passing the bedroom, glanced inside. The room was neat. The bed was made. Family pictures dotted the dresser top. A small mirror hung on the wall. Beside the bed, on one of those crudely tanned black-and-white Colobus monkey rugs that were hawked on the streets of Addis, were Ted’s bedroom slippers. Next to them was another pair, tiny enough to be worn by a child.

I kept walking, out through the front door and onto the wooden veranda. I could see for miles across the flat landscape. I stared at the horizon trying to decide what to do.

Returning to the house when the tea was served, I found Ted sorting through his mail. Ayana had disappeared.

I poured my tea and asked Ted if he had gotten permission from the Peace Corps Director to get married. I knew the answer. Ted shook his head “no.” In a rush of words, he told me what had happened.

He had met Ayana the year before. She was the daughter of his maid. They had fallen in love and were married in a Muslim ceremony that August. One of his students had arranged everything and Ted had paid Ayana’s father two hundred and fifty birr — Ethiopian dollars — for his daughter. As a gesture of good will, he also bought a goat for her mother.

No one knew exactly how old the girl was — she had no birth certificate — but he thought she was fourteen or fifteen. His plan was that after his tour was over in July, they would go to America and he’d start graduate school in the fall.

I asked him what people in Bati thought of the marriage and he said no one cared except the Irish missionaries, who were very upset.

I knew I couldn’t keep the marriage secret from the Peace Corps office or the American Embassy. Nor from other Volunteers, who would certainly hear of it — as would everyone else in the international community. I also assumed the Ministry of Education had already heard about it from Ted’s headmaster.

Besides all that, I was concerned about Ted’s mental health. I wanted someone more qualified than myself to talk to him.

“Ted, have you had your yearly physical?” I asked, thinking if he went to Addis, the Peace Corps doctor could talk to him.

Ted shook his head.

“I think you should do it before you’re too far into the semester.”

He nodded “okay,” and I suspected he knew something like that would be coming once I reached Bati and found out he was married.

I left Ted’s house before nightfall. The Danakil women were gone from the market. The hillside was bare and brown. The sun was behind the highland shelf that stretched the length of Ethiopia and silhouetted the small and thorny trees, and the chikka houses of sticks with mud mortar. This was the pale, neutral part of the day, before the rush of cool, desert night air. Small birds flew in swift, silent patterns. Within minutes, the moment passed. Darkness gathered up the ground.

Climbing into the Land Rover, a chill seized my shoulders. I shook myself and flipped on the vehicle’s high beams. They lit up the compound like sentry lights.

EARLY THE NEXT DAY, I went to see Ted’s classroom and met the headmaster of the middle school where he taught. On the narrow two-lane road and across the surrounding savannah, I saw students walking barefoot toward the school building.

They assembled in the dirt yard in front of the building and waited for the first bell and the morning ceremonies — the national anthem, and a prayer. Some of the boys were playing a makeshift game of soccer using a ball of eucalyptus leaves strapped together by strands of leather.

The girls stood off to the side in clusters, all wearing thin, ankle-length cotton dresses, their black hair combed into tight tribal braids. A few wore a style of plastic shoes made in China that I would, years later, see sold in fashionable boutiques in New York City.

Few of these students, I knew, would continue their education beyond the crumbling walls of this school. In 1967 there were less than fifteen hundred schools in the Empire. By bringing in Peace Corps Volunteers, the Emperor had doubled the number of teachers and expanded enrollment and the number of schools.

Visiting the headmasters where Volunteers taught was one of my essential tasks, a way of showing that the Peace Corps was there to help. Headmasters of remote schools had little education themselves, perhaps a few years of primary school. Almost none of them spoke English.

The headmaster in Bati was a shy man in his early forties. As I was ushered into his office, he came forward to greet me, bowing and clasping my hand with both of his — the customary way of meeting a stranger.

I presented my card — printed in English and Amharic — which gave him my name, and title and organization. While we talked, he held the card carefully as if it were something of value.

He knew a little English, and with my limited Amharic, we managed to make small talk about the town, his job, and the volunteer who was teaching in his school. Ted was doing a wonderful job, the headmaster told me, nodding with pleasure and thanks.

From the headmaster, I received permission for Ted to leave school and go to Addis Ababa, saying Volunteers were required to see a doctor once a year. I had wondered whether he would bring up anything about the marriage, but he did not. That wasn’t the Ethiopian way.

On my road trips, I always made a point of visiting the classrooms of Volunteers. They thought it was so I could evaluate them, but in truth, it was meant as a gesture of support — congratulations, even. The Volunteers didn’t need to be checked-up on; most of them had the training and experience to do more than adequate work.

In my own tours as a Volunteer and then as a staff member, I only saw two Volunteers who were hopeless teachers. Ted was one of them.

He taught sixth grade. As I entered the classroom, there was a flurry of whispers as the students in the crowded space stood up, showing their respect to an adult, and a foreigner. I took a seat in the back on a narrow bench, and nodded hello to Ted.

He was teaching a class in African geography and the students stared silently at him as he pointed at different nations on the large map — a rare bounty in the provinces, where textbooks and other educational materials were scarce. My guess was that Ted had bought the map himself at the only bookstore in Addis Ababa.

As Ted identified capital cities one by one, the students called out their names. Ted kept his back to them the entire time.

I left the classroom after ten minutes, unable to witness his lack of teaching skills.

Dessie with the escarpment in the distance

BY ELEVEN IN THE MORING I was eager to leave Bati. It was already hot, and by midday it would be even hotter. With two hours of steady driving, I could get to Dessie, the capital of the province. Located at an altitude of 6,500 feet, Dessie was in a forest of eucalyptus that made the town green, wet and cool. In the town I could also find a phone; I needed to call Addis and tell the Peace Corps office about Ted’s marriage.

The road into Dessie, built during the Italian occupation, follows the slope of the terrain, curving along an endless succession of high hills. One of the last few turns affords a glimpse of Dessie’s tin roofs. Then, at the crest of the last hill, the road bursts into the central square, crowded with people and herds of livestock.

Dessie had the atmosphere of a western frontier town: wooden buildings with porches, a steady flow of cattle. Everywhere there were mules ridden by tilik sews (important men) in the traditional white shammas (cotton, hand woven wraps, shawls) and jodhpurs.

Each tilik sew would have the large toe of his bare foot hooked into one of the metal stirrups, in the fashion of days before the wider metal erkas stirrups became common in the provinces. In the entourage trailing behind him, you would see a boy — a young son, perhaps a relative, a family retainer, or, in some sections of the country, an indentured servant — carrying the tile sews shoes.

Depending on his importance, and the distance he had come, the tilik sew would be accompanied by one or two armed guards, or as many as a half dozen, all armed with old Italian rifles. Most often, guards traveled with tilik sews who were carrying money that they were taking to the provincial bank. These guards guided their patron on the dangerous, unpredictable plateaus surrounding Dessie.

THE TOWN HAD AN old hotel left over from the occupation by the Italians; there I would make my phone call to Addis and find a room for the night. The hotel was owned by an elderly, coarse-looking Italian woman who was sitting in the parlor when I approached the desk and signed in. From the depths of an overstuffed chair, she snapped orders to the staff as she chain-smoked cheap Ethiopian Nyala cigarettes.

In the evenings, I knew, the parlor would be filled with Italian men. Most had come during World War II and stayed after the occupation, marrying Ethiopian women and fathering families. At night, they’d collect at the hotel for a cup of espresso or a glass of local brandy. Listening to a radio tuned to a football (soccer) game broadcast on shortwave from Italy, they greeted each other with nods and whispers, said very little, and smoked intensely. Wearing double-breasted suits of heavy, ill-fitting cloth that draped loosely over their wizened bodies, the group resembled a grove of olive trees, hard-twisted by the wind and sun and age.

I CARRIED A SMALL VALISE and a book bag up to my room, then came back down to telephone the Peace Corps.

Reaching the capital was not easy. In Amharic, I told the local operator I wanted to place a “Lightning” call to Addis. “Lightning” was the Ethiopian term for an emergency communication that would take priority on the limited lines to the capital. Even so, I was prepared for it to take the rest of the day to connect.

While I waited, I went into the empty hotel restaurant and sat at a table facing the gardens. I’d just started on a huge lunch of soup and pasta and crème caramel when the hotel phone rang out in a sharp series of loud, hysterical bursts.

The call had miraculously connected with Addis and the Director was already on the line. I quickly told him my news, afraid that the line might go dead before I finished the call.

“We have a situation in Bati. Ted has married his housekeeper’s daughter over the summer.”

There was silence at the other end.

“And to the best of anyone’s knowledge, the girl is only fourteen,” I continued.

“Fourteen!” he exclaimed. “Does she speak English?”

“No. Nor can she write or read Amharic.”

“How good is his Amharic?”

“Not sure, but I’m guessing his bedroom Amharic is pretty good.”

“Did we know about this?”

“We do now.”

I paused to let him comprehend all that news.

“He’s on his way to Addis. I told him he had to get his physical. That was my excuse, but he knows what’s going on. He should be there tomorrow, so you can alert everyone.”

“What about you?”

“I’m driving up the to Mekele. I’ll be back in two weeks”

“Okay, we’ll see you then. Have a safe trip.”

“One thing,” I asked quickly. “Please don’t make any decisions until I’m back, okay? I want to be part of what goes down with Ted. He’s one of my Volunteers.”

“Don’t worry, I’ll wait for you. We’ll need someone to blame.” He laughed. “See you in two weeks. Drive carefully.” He hung up.

From Dessie, I headed up the road, traveling north to Mekele, then west to Axum, and finally south on the Gondar Road. Along the way, I stopped in dozens of towns with Volunteers. By the time I returned to Addis Ababa, Ted had come and gone.

“He’s not crazy,” the Peace Corps doctor told me, “just in love.”

In a string of meetings with officials in and out of the office, I gathered that the Civil Code of Ethiopia recognized a Muslim wedding. If Ted wanted it honored by the United States government, he had to have the marriage registered at the Embassy.

In talking to ex-pats, I learned that in Ethiopia during previous periods it was common practice for travelers in remote areas to make arrangements with a woman not only to cook and clean for them, but also to share their bed. No one thought Ted’s liaison would last longer than his tour.

The Canadian Jesuit who was headmaster of Addis’s Tafari Makonnen Secondary School speculated that whether legal or not, customary or not, the arrangement was doomed. How would an illiterate child-wife survive on an American college campus?

THE PEACE CORPS DIRECTOR decided he wanted to see the Bati situation for himself.

To arrange his visit, I drove up the Dessie Road a few days beforehand. We would meet when he flew in by chartered plane. I reached Kombolcha, about 26 kilometers from Bati, the night before the director’s arrival, and stayed at the Agip gas station, a refueling depot with a few rooms for rent. Early the next morning, I drove out of town to a grassy air strip and sat on the hood of my Rover and waited for the Cessna to arrive.

One falls in love with Africa at such times when the continent seems so still. I remembered camping once down in the Rift Valley, on the shores of Lake Langano. I woke up after midnight in my sleeping bag and looked into a clear sky at the Milky Way.

Now, on the horizon, a dark spot moved, came closer and resolved into the image of a small plane. Swooping down into an easy glide, it settled on the flat empty strip of land and taxied over to where I sat. The young French pilot cut the engine, and waved hello from the cockpit as the director jumped out. He walked over and slid into the passenger seat of the Land Rover, and together we waited and watched as the Cessna taxied out onto the strip and took off again, lifting off in a matter of minutes. Then we were on the move ourselves, fifteen kilometers of sharp turns on mountain roads and through a one-hundred-yard-long tunnel that took us suddenly to a cultivated valley covered with scrubs, euphorbia, and acacia.

I HAD SENT WORD that we would be arriving that day, so Ted was home and not surprised when we knocked on his door. Ayana had gone to the market, he said. We would go there now and see her.

We went, but never saw her.

Later, Ted told me how Ayana had watched us from a distance as we toured the crowded stalls. She might not speak English or know how to write or read, but she was smart enough to keep out of sight, understanding that this sudden influx of faranjoch (foreigners) did not bode well for her.

If the director had been BEEN a lawyer or a government bureaucrat, my guess is that he might have come up with a simple enough solution: to send Ted packing back to America, with or without his child-bride. However, he was an academic, a man in his early thirties with a shaved head and a careful, quiet demeanor. He smoked cigarettes with great deliberation, made decisions with the same thoughtfulness, and I can’t remember him ever raising his voice.

Waving his cigarette hand, so as to leave a wisp of smoke in the front of the Rover, he told me he was prepared to let the romance play out without official pronouncement. The Volunteer had less than a year left in his Peace Corps tour. “Why start a ruckus?”

“Is that what you told Ted?” I asked.

He nodded, then after a moment added, “We need to keep this marriage quiet.”

“I agree, but that’s difficult with the PCV network. Volunteers know everything.”

“Well, there’s the advantage of Ted being in a one-man site. He doesn’t leave Bati often, and certainly not now with a new wife.”

“True enough. Did you suggest anything to him about what he should do?”

“Yes, I did.” He glanced over at me as I maneuvered the Land Rover around the curves of the road back up to Kombolcha. “I told him not to get her pregnant.”

A FEW MONTHS LATER, in March of 1968, I was back in Bati, and Ted told me his news.

Ayana was pregnant.

If he wanted to have legal rights as a father he had work to do. The marriage had to be registered with both governments, Ethiopian and American. That meant another trip to Addis Ababa and Ayana would have to go with him. It would be the first time she had ever left Bati.

Ethiopian law, at the time, gave rights to the mother for the first years of the child’s life and then the father became the primary legal guardian. In other words, Ted could take his child out of Ethiopia once the baby reached the age of reason, even if he was divorced from Ayana.

Meanwhile, our Peace Corps doctors were in touch with the medical staff at the hospital in Dessie, the only one in the province. A Yugoslavian physician working there remarked that they could handle the matter with an abortion. By that time, however, Ayana was in her second trimester. The Peace Corps doctors were outraged at the suggestion.

ANAYA AND TED took the day-long bus ride into the capital and spent what was left of his school break registering their marriage with both the Ethiopian government and the U.S. Embassy. Ayana was also examined by the Peace Corps doctor.

It was while the couple was staying with me, in my two-bedroom house in Addis, that I recognized the profound changes Ayana had made in Ted’s personality. He was more outgoing and social than I had ever known him to be. And despite Ayana’s limited English, he worked hard to draw her into our dinner table conversation. She’d brought out a core goodness in him that I’d never realized he had.

She even made my life better, brightening up my place every day with fresh flowers picked from the abundant wild plants that grew in the compound. And despite growing up in Bati, she had somehow learned to cook western food, and she took the trouble to teach some of what she knew to Gebra, the cook-housekeeper I employed.

But what was most enjoyable was seeing the love they shared. Like most Ethiopian women, Ayana was not publicly affectionate, but as their housemate, I caught glimpses: the lingering look she gave Ted when he was leaving the house, the way she dropped her deep brown eyes with a flutter of lashes when he approached her upon returning home.

IT WAS WHILE they were staying with me, that Ted learned he had won a Danforth Scholarship, and in the fall would be starting Ph.D. studies in history at Harvard. Within a year, Ayana, who now spoke a little English, but could not read or write in any language, would be attending graduate school parties in Cambridge. I was already feeling sorry for her, imagining her suffering through snowy Boston winters after a childhood in Africa, and dealing with the rush of traffic and crowds of pedestrians, coming as she did from a remote Ethiopian village on the edge of the Danakil.

Meanwhile, Ted’s tour was ending soon — in July — and he was making arrangements for where Ayana would give birth to their child. He took a bus up to Dessie and rented her a room in a house close to the hospital. He also opened a bank account for her, where she could take out 50 birr a month, signing for it with her Amharic version of an X.

He was arranging things in advance for Ayana because he wouldn’t be there for the birth. By the time the child arrived in October, Ted would be at Harvard in graduate school. Then, when the infant was old enough to travel, Ayana and the child would join him in America. At least, that was his plan.

I VISITED TED AND AYANA in Bati on an average of once a month for the rest of that school term, and for the most part everything proceeded normally. Ted was dutiful about seeing that Ayana was taken care of by the doctors in Dessie. Regularly the couple took the long bus ride up the escarpment to the hospital. Then, before leaving Bati for the last time, he moved Ayana to the room he had rented for her in the provincial capital.

He said goodbye to Ayana in late June, after school ended for the year. His Peace Corps tour was over and he came down to Addis Ababa to catch a flight home. That morning I took him out to Haile Selassie I Airport southeast of the city on the old Bole Road.

One reason I gave him a lift was that I wanted to make sure he got on the flight. Having seen him go with my own eyes, I knew I could breathe easier. I would be leaving Addis in September myself, so these were my final months as Peace Corps staff. I needed to spend the time opening sites for new Volunteers coming to Ethiopia that fall and closing down my life in Africa. I didn’t need any more Ted complications.

LATE ON A RAINY AFTERNOON in early September, two weeks before I was scheduled to leave the country, I was driving through Arat Kilo Roundabout and spotted Ted. He was standing alone in front of the Ministry of Education with a duffle bag beside him. I spun my Land Rover over to the curb and slammed on the brakes.

He seemed as surprised as I was, seeing each other in Addis just months after we’d shaken hands goodbye at the airport. He had his usual haggard look as if he hadn’t a good night’s sleep in several days.

“Is everything all right with Ayana?” I asked as he climbed into the Rover.

“Everything is okay.”

“Then why are you Addis?

“It’s a long story.” He looked, at that moment, relieved just to be out of the afternoon rain.

“Do you have a place to stay?” I moved the car back into the roundabout.

He shook his head. Hunched over in the front seat, shivering with cold, he wedged both hands between his legs and explained he had arrived that morning and had gone immediately to the Ministry to see about a teaching job. Under the driving rain drumming the roof of the Rover, I had to strain to hear his familiar soft monotone.

As I drove, I made a decision. Instead of taking him to the Peace Corps office, which was a block away from Arat Kilo, I swung right and went past the University, down Queen Elizabeth Street to my house. He was no longer my responsibility, but he needed help.

I started a fire in the front room fireplace, which provided the only heat in the house, and Ted settled down in front of the blaze with a cup of coffee, and summed up what had happened in the few months since he’d left Ethiopia. It wasn’t a happy narrative.

Ted’s first stop in the U.S. wasn’t Boston, it was North Dakota, where his family lived in a small town, and where he’d grown up. He arrived there to find a draft notice waiting. The Peace Corps had kept him out of Vietnam for two years, but now he was twenty-four and, in the eyes of his draft board, still eligible for the Army. On his first day home, he paid them a visit and told them he couldn’t be drafted. He was married. His wife was pregnant. As proof, he showed them his marriage certificate from the American Embassy. He also told them about the Danforth and Harvard, and how his wife would soon join him in Boston.

The board was not impressed.

In order not to be drafted, Ted was told, he had to be living with his wife. He had to return to Ethiopia or go to Vietnam. That was his first problem, Ted said.

The next problem was his parents, who weren’t simply shocked that their son had married an Ethiopian Muslim, they were enraged, especially his minister father. His family shattered, Ted decided to leave home. Two months after leaving Addis, he was back on a plane, headed to New York and then to Ethiopia.

Just before boarding the flight for Addis Ababa, however, he’d been called to the telephone in the airport. His father was on the line. He did not want Ted to leave America thinking he couldn’t come home again. All was forgiven. That phone call from his dad had calmed his soul.

NOW TED HAD TO get on with his life. He was unemployed, broke, and in need of a job in Ethiopia to support himself, his wife, and soon, their first born.

I could help him; I had a good friend at the Ministry of Education, Ato (Mr.) Adam. He had earned his college degree in Iowa and returned to Ethiopia to become the Headmaster at two schools before being appointed Director of Secondary Education for the Empire.

The next day, I went to see Adam and explained about Ted and his situation. Not only did Ted need a teaching position, I said, but the school had to be near a hospital — a challenge at that time in Ethiopia when there weren’t many medical facilities outside of major cities.

The first question my friend asked was, “Is he a good teacher?” Adam’s vast, oversized office, with its high ceiling and massive furniture, made both us look small and unimportant.

When I didn’t respond immediately, Adam smiled and leaned back in his leather chair. He knew I wouldn’t lie to him, so he correctly interpreted my discomfort. I admitted that Ted “wasn’t the best Peace Corps teacher” but I made a pitch for him anyway. Not only did he need a job, but because of the hospital issues it would have to be in a city.

Adam listened, nodded, and then, after a moment of contemplation, leaned forward and asked seriously why was I going out of my way to help Ted, who was a terrible teacher and no longer in the Peace Corps.

I shrugged and said simply that Ted had been one of my Volunteers and I couldn’t abandon him.

He understood and told me to have Ted come to see him. He’d work something out.

I took a deep breath. Ted was going to be okay.

Within days, Ted was assigned to teach English in Gondar, the capital of Begemder Province. Not only was there a hospital in the city, but it was staffed by American doctors.

TED CAME TO THE PEACE CORPS OFFICE to say goodbye. He was going by bus to Dessie to pick up Ayana, and they would then travel another two days to reach Gondar and find a place to live before the school semester began.

I suggested that he use my office and telephone Ayana in Dessie to let her know the news and that he was on his way.

Ted shook his head. Ayana had never used a telephone, he explained. “She doesn’t even know what they are. She wouldn’t believe it was me on the phone. She has to see me before she believes that it is really me.”

BEFORE WE SAID GOODBYE AGAIN, I had told him to write and tell me how it was going. And he did write . . . more than two years later. Not knowing where I was in the world, he sent his letter, addressed to me care of the Peace Corps Headquarters in Washington, D.C.

By that time I had been out of the Peace Corps for several years and was a dean at a college in New York, but someone at the Agency knew my name, and where I was and was kind enough to forward the letter.

That’s how I learned Ted had returned to the States and was living in North Dakota with Ayana and their daughter. He was writing, he said because he needed a recommendation. He was applying for a high school teaching position in his hometown and thought I might help.

It was an ethical dilemma. Ted was perhaps the worst teacher I had ever seen in a Peace Corps classroom. Was it right to subject the teenagers of North Dakota to that kind of experience? I didn’t respect Ted as a teacher and I wasn’t close to him. Then again, I had witnessed everything Ted had lived through, all the hurdles that had stood in the way of his living a happy life with his Ethiopian wife and their child. He could have abandoned her anywhere along the way, but he had not. Could I refuse to help him begin a new a life in America?

I sat down at my desk and filled out the form from the North Dakota high school. The recommendation I wrote for Ted was glowing. I told myself that at least the kids would learn a lot about Ethiopia.

THIRTY YEARS LATER, in the mid-nineties, I returned to work at the Peace Corps. I had come back to the Peace Corps to be manager of a six-state recruitment office located in New York City.

One day, toward the end of my five years there, I received a telephone call from the career services office at St. Lawrence University, a small school in upstate New York. The director asked if we could send a recruiter to their campus, as a number of students were interested in joining the Peace Corps. We didn’t have enough staff members to visit every college, and St. Lawrence was not on our list, but the director wouldn’t give up easily; he offered to pay for the recruiter’s plane ticket to and from New York City.

We wouldn’t take his money, and all my recruiters were committed to other, schools, so I decided I’d go. I flew to Syracuse, then drove north to the college. I had arranged to speak to students that evening, stay overnight, and visit classes the following day to talk about Peace Corps opportunities.

HEADING NORTH ON ROUTE 81 to Watertown, then northeast to Canton, I had three hours of driving on rural country highways. It reminded me of being in my Land Rover back in Ethiopia, riding those empty roads across the Highlands, from one distant town to the next.

Arriving at the university, I checked in with the career services office, then dropped off my things in my room at the guest house. My first meeting was at the library and I walked across campus to the lecture room.

Arriving at the university, I checked in with the career services office, then dropped off my things in my room at the guest house. My first meeting was at the library and I walked across campus to the lecture room.

It had been some time since I had last been in a college library, and it was a treat. I wandered around, walked through the periodical section, glancing at the scholarly journals on international topics that filled the shelves.

I wasn’t looking for any particular publication, but one caught my eye. On the cover of The Journal of African History I spotted the word Ethiopia. I stepped over and picked up the magazine and there in bold type was Ted’s name. He had written the article.

Flipping the magazine open, I read a brief biography of Ted’s life after the Peace Corps. He had a Ph.D. in African Studies, was teaching at a southern university, and the author of several books on Ethiopia. There was also a list of his scholarly publications, plus the academic awards he had won. The journal touted him as an authority who had lectured at dozens of prestigious universities. It said also that he was married to an Ethiopian and their daughter was a flight attendant.

I sank down into a chair and stared at the article.

Ted was alive and well. A college professor. An authority on Ethiopia. And I had had to steel myself to embellish his recommendation so he could get his first teaching job!

I looked up at the clock. It was time to speak to the St. Lawrence students. I put the magazine back in its rack, then paused, and reached for it again. I would use the journal as a show and tell, I thought, walking towards the lecture room at the rear of the library. The publication would illustrate how a Peace Corps tour could do great things for your resume.

Would I tell them the rest? Would I warn them that a Peace Corps tour could have unforeseen consequences? If I didn’t, they’d have no way of knowing what could happen if they took a left turn off their Western ways and found themselves on a two-lane tarmac road taking them into unfamiliar terrain — a place where they’d find a cluster of small hills and blossoming passion flowers, a place where they’d encounter a totally different way of living and lose, not their lives, but their hearts.

John,

You just provided the reason why your next novel should be: Tales of the Peace Corps: Where You Can Lose not your Life but your Heart.

I was driven to finish this long short story. Utterly smitten with the compelling narrative. Thanks, John. Kudos.

Patricia Edmisten

Thank you, Patricia

Patricia Behler here, a companion PCV with Patricia Edmisten in Peru 1962-64. With my 94 year old brain still mostly intact, your writing calls up to me the many cherished, unexpected memories of living in Arequipa, Peru, and still calling my friends there, mi familia Arequipana.

Thanks…!

Thank you, Patricia. Like you I’m “hanging in there”. I was in Ethiopia with the first Vols in 1962-64, like you.

Keep them coming, John

A wonderful work, John. We drove and hiked in the same circles (!), so I especially appreciated your descriptions of some of the trials and tribulations of frequently unsung heroes among the PC Staff. What a great O. Henry ending to your story. Thanks for posting this.

Great story, John! I read it in awe at your descriptive powers and in them summoning up my own experiences in Gabon. Though I wasn’t clear why the narrator saw Ted as being an incompetent teacher I loved your characterizations of the two lovers and the whole Ethiopian vibe. The same angelic writing style is also apparent in The Searing and Caddie/Hickory. Now I wonder if you and Paul Theroux serve as each other’s first readers?!?:) Eric Madeen P.S. But one niggling thought after finishing this LONNGGG piece: why do you want me to cut my Schweitzer article which is much shorter … ?

???????

This is the second time I’ve read this piece and just like the first time, I finished it with tears in my eyes. What a lovely story. I find it to be also a story of the dedication and persistence of a Peace Corps staffer who goes above and beyond. I think that’s also comes from a big heart.

Thank you for the story, which I very much enjoyed. Came across it quite by accident.

The Northern Irish missionaries beside the Italian hotel on the outskirts of Bari were my uncle and aunt, John and Martie Flynn. I spent a gap year there in 1974. Much of what you write brings back many memories. The drive to Dessie taking patients to hospital; having doro wat at Tekeli’s in Kombolcha; filling up with petrol at Agip. I was there a few years later and it was in the aftermath of a very severe famine in the area so the ambiance was very different in many ways, but still fundamentally unchanged. I went daily into The famine relief camp in Bari where many were those ferociously independent Danakil women and their children driven out of the Danikil by starvation. But they were the warmest of people still with the vestiges of that striking beauty.

I don’t think there were any PC volunteers when I was there, but there were books in my relatives’ house that had been left behind by volunteers.

Although only 18 at the time, my visit to Bati had an immense impact on my life. I am now living in S Africa working with disadvantaged children and having 4 adopted children.

With warmest best wishes, Alan Gaston