A Writer Writes — “Up On The Mountain” by Michael Beede

Up On The Mountain

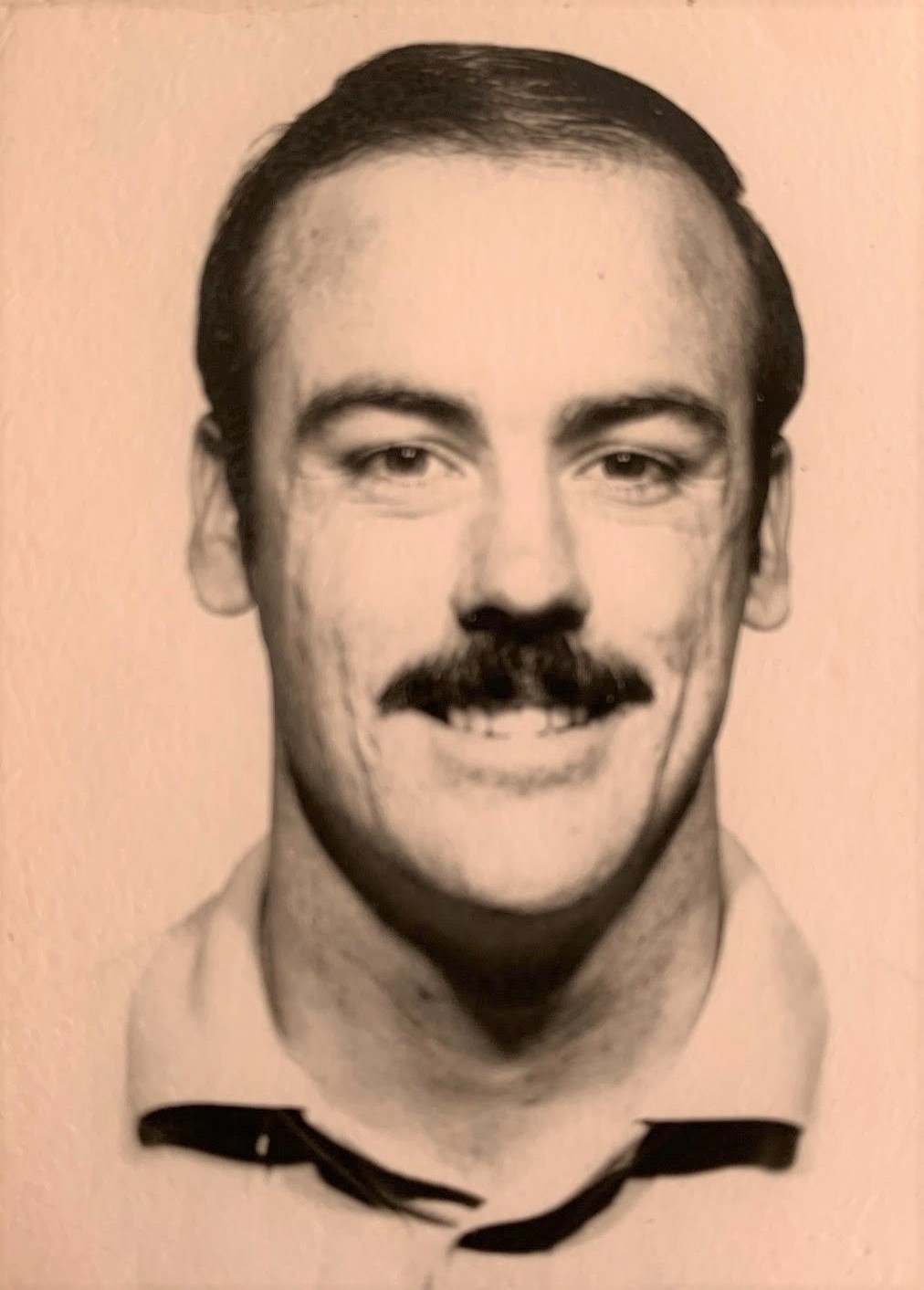

by Michael Beede (Peru 1963-65) and (Venezuela 1968-70)

From March of 1963 to February of 1965, my good friend, Ron Arias, and I served as Peace Corps volunteers in the high Sierra town of Sicuani in the Departamento de Cuzco, Peru. I was 20 years old, and Ron was a year older. We had been assigned to the PNAE, Peru’s National School Lunch Program, and we were having the time of our lives.

School holidays and vacations provided the time and opportunity to explore in the Andean Cordillera surrounding Sicuani. There were backcountry regions in those mountains where few foreigners, if any, had ever ventured. The march of civilization was rapidly changing the environment forever. The time to visit these isolated places while they were still in a relatively untouched state was fast ebbing away. The opportunity to do so was now. We were young and excited by the prospect of the adventure that awaited us, and there was no holding us back.

Ron and I made a trek on horseback high up into the Andean backcountry behind Sicuani to fish and hunt. We had been invited to stay at an alpaca hacienda owned and operated by the Maranganí Textile Factory in Marangani, a small nearby town. A local acquaintance of ours was the company manager. He drove our gear and us further up the valley from Maranganí to a rendezvous point where we were met by ranch hands with saddled horses sent by the hacienda’s mayordomo, the ranch foreman, with orders to guide us safely to our destination.

The alpaca hacienda was situated at an altitude of 14,000 feet, way above the treeline. Here amid the rocky crags, the ranch’s alpaca herds grazed on slopes covered with a dry, yellow grass pasture. It was bitterly cold, and the air was so thin that even the effort of horseback riding left our horses and us gasping for oxygen.

Before we could reach the safety and shelter of the hacienda, it began to snow heavily, and the temperature dropped precipitously to well below zero. The snow fell so thickly that the surrounding terrain was covered in a uniform whiteness that blurred and obliterated all distinctions between sky and land. Before we knew it, we were enveloped in a total whiteout and at a loss as to how to proceed. At our guide’s signal, we halted and dismounted to wait for a break in the snow flurries. It would have been madness to go on. The narrow trail was steep, and it was impossible to see more than a couple of feet in any direction. If there were any sudden drop-offs around the next bend, it could have become fatal in the blink of an eye. So we stood there shivering, waiting for the weather to clear.

Fortunately, we did not have long to wait. As the storm lifted, we could discern a cloaked figure on horseback descending towards us from the heights above. Oh happy day, help was on the way. It was one of the ranch hands from the alpaca hacienda we were to visit. Alarmed by the abruptness and severity of the storm, the foreman had sent a hand to locate and guide us to safety. Happily, the hacienda was only a short distance away in a shallow, protected depression just over the next ridgeline. There was no more welcome sight than the tumbled down adobe hovel that was the hacienda’s main building.

We dismounted as quickly as our frozen limbs, encased in heavy parkas and ponchos, would allow. We stumbled, mummy-like, through the structure’s only door into a smoke-filled, dimly lit, low ceilinged room. A fire fed with the round, dried pellets of alpaca dung generated a thick and acrid smoke. It was overpowering and suffocating, turning our eyes red and tearful instantly. But it was gloriously warm in this malodorous inferno and shielded from the piercing cold of the winds howling just outside the walls. We rubbed our hands and hovered over those smoking, glowing mounds of dung just as lovingly as if they were censers of frankincense and myrrh.

It was now late in the day and time to turn our attention to setting up our accommodations for the night. The floor of the one-room shack was of packed earth upon whose uneven, lumpy surface we made our beds. Once we had sufficiently warmed up our frozen bodies, we ventured outside to gather bundles of dry pasture grass for bedding. This took several trips and great courage since it was still blowing up a storm and was cold as hell out there. We made a couple of cozy nests on either side of the heating fire where we spread out our sleeping bags. We were close enough to the fire to enjoy the maximum amount of heat without running the risk of igniting the straw bedding. When we laid down on our floor beds, we discovered an unexpected bonus. We were low enough to escape most of the fetid clouds of smoke emanating from the smoldering mounds of alpaca dung. It was a win-win situation, after all.

We sorted out the rest of our gear, making sure to put the .22 rifle and ammunition as far away from the fire and out of harm’s way as possible. There were a bare minimum of cooking utensils and food provisions, sure that we would bag enough game to make due. We had one pot that would universally serve to boil water for coffee and tea as well as prepare rice, oatmeal, and pasta. There was a small frying pan to cook up the trout and game that hopefully would come our way, a couple of knives, forks, spoons, and our trusty Buck pocket knives. Just in case the hunting didn’t pan out, there were hand lines, a rod, reel and lures for fishing, as well as a modest supply of instant coffee, tea, sugar, a bottle of cooking oil, assorted canned meats, sardines, and chocolate bars.

Settled in comfortably, we now had some time to kick back and relax. The foreman was a generous host and soon began to ply us with hot cups of steaming tea. To our delight, we discovered that this beverage was heavily sweetened with sugar and liberally laced with aguardiente, a local 90 proof cane alcohol that was Peru’s answer to white lightning. Under the circumstances, this was just what we needed to warm up our bodies and relax our souls. Ron and I gulped down cup after cup of this delicious elixir accompanying each round with increasingly hardy toasts to friendship and the brotherhood of man. In retrospect, we learned that drinking alcohol like this at 14,000 feet in the Andes had its disastrous side effects. After much bonhomie and too much aguardiente, we were all totally blasted.

It was time to call it a night. We stumbled outside in the howling Arctic gale for a final pee before staggering off to bed. We had sleeping bags and because it was so cold, or because we were so drunk, or, perhaps because of all of the above, slept in them fully dressed. Getting into the bags and zipping them up would have been a hilarious sight for a sober observer. For Ron and I, it was unadulterated torture accompanied by a tangled slur of obscenities directed at sleeping bag manufacturers, their mothers, and grandmothers before them. Once in the bag, I collapsed on the makeshift bed and passed out in an alcoholic stupor. My struggles were over for the night.

Ron did not have the same good fortune. Snuggly zipped up in his sleeping bag; he sprawled on his back, facing up towards the smoke-blackened rafters of the shanty’s ceiling. Instead of the sweet deliverance of drunken oblivion, Ron descended into a nightmarish realm of Dantesque proportions. The room began to rotate slowly and then spun wildly out of control. The sickening odor of the alpaca dung fires was suffocating and combined with the cloying sweetness of the aguardiente laced tea was an instant formula for nausea.

Ron’s immediate reaction to get up and rush outside to retch was thwarted by the imprisoning confines of the sleeping bag. He was totally encased in this cocoon with his head inside the bag, and only a small hole left open for breathing. His arms were pinned to his side, and when he finally struggled free found that the zipper was stuck! Now it was too late. It was all over. The involuntary physical reactions kicked in, and he puked his guts out right where he lay. It was literally like drowning in your own vomit. More precisely, it was like being trussed up in a sack unable to escape and waterboarded in your own puke. The panic it provoked must have been total. Only the blessed unconsciousness of alcoholic stupor brought him temporary release from the horror and repugnance.

I had slept oblivious through it all. My first recollection of returning consciousness was of faint calls for help coming through the cobwebs of a hellacious hangover. It was Ron. Still imprisoned in his sleeping bag, he had managed to squirm his way over to where I lay. His muffled calls came from inside the bag, and there was the unmistakable, pungent foulness of vomit. It was like coming out of a bad dream. Surreal better describes it. My mind slowly brought the scene into focus, and I was startled back into consciousness. I was able to unzip my bag and jump out. From the outside, I was quickly able to unzip Ron’s bag. He was free at last, but quite a mess. We can joke about it now, but at the time, it was no laughing matter.

In spite of this self-inflicted disaster, we carried on with the hunting trip as planned. Groggy in our hung-over state, we struggled through a perfunctory breakfast of instant coffee and a packet of Galletas Maria crackers. We gathered our hunting gear and stumbled out of the acrid foulness of our shack. The intensity of the predawn cold and the thinness of the air at 14,000 ft slammed into us like a freight train. It was sobering but only in the sense that you were clearly aware of the monstrous migraine pounding mercilessly within your skull. We were still legally drunk. Now, before the sun was fully up, we had to find the horses, saddle up and get into position to ambush our unsuspecting prey. No easy task, but fortunately the horses were hobbled and nearby. Our noble beasts of burden were as unenthusiastic about this early mourning venture as we were.

The local game we were after included the cunning vizcacha, a rodent, and member of the chinchilla family that looked like a cross between a squirrel and a rabbit. This little creature lived in colonies in the crevices of rocky outcrops in the high Andes. I imagined that during the few short hours of daylight, they emerged from their apartment-like complexes to feed on whatever vegetable matter they could scrounge up in the harsh, rocky environment and bask in the warmth of the sun. The vizcacha was highly prized by the locals as a meat source, which probably explains why they were such elusive little bastards. However, just like squirrels, it takes a few to make a meal.

The mayordomo gave us some pretty detailed directions to the nearest and most promising vizcacha hunting grounds. The only trouble was that the instructions were half in Quechua, the ancient dialect of the Incas, and half in Spanish. All was uttered with a lisping Andean inflection that rendered communication almost unintelligible. What we could discern was that the place was on up the mountain, over the rise and into a little marshy valley with a stream running through it, near a rocky draw. And sure enough, that was right where it was.

Just before sunrise, we took up position in some boulders that overlooked a likely pile of rocks about 150 feet below us. Ron and I were both hunting novices. We only had the one .22 rifle between us so we would have to take turns shooting. No practice rounds, no sighting in the rifle, and no scope. Just, god bless the lucky bastard that happened to hit the mark. This was shooting from the hip in the real sense of the word.

I guess I had envisioned hoards of vizcacha teeming out on to the rocks below, complete with sunglasses, lotion, and umbrellas jostling for positions to sun themselves. This isn’t how they do it at all. Sunning consists of cautiously sticking a quivering little tip of a nose and tail up over a rock and presenting a couple of inches of a brownish grey fur target area for a few seconds before ducking back into a protective crevice.

The viscacha were there in the rocks all right, but teeming they were not. They were far and few between, and only the most patient observer was rewarded with a fleeting glimpse. If you shot and missed, the whole tribe was gone for the rest of the day. This was the case even if your shot didn’t miss. So you had to be dead on and hope the little critter died instantly before it could dive back into the rocks and, dead or alive, be lost forever.

So there we sat shivering in the bitter cold, bundled up like a couple of Eskimos waiting for dawn’s early light to signal the commencement of the rodent slaughter. I forget who shot first. I do remember that when my turn came. I intently stared down the barrel of the .22 and fervently hoped the little bastards would do me the courtesy of moving into my sights and standing still long enough for me to get off a good shot. Which they didn’t do, of course, and the resulting fruitless fusillades sounded like something out of Custer’s Last Stand. The vizcacha vanished as if by magic, disappearing instantly, deep into their lairs. There they stayed for the remainder of the day probably frantically phoning nearby colonies to warn them of two lunatic gunmen on the loose, prowling the area with blood in their eyes, firing indiscriminately at anything that moved.

The vizcacha had won the first round hands down. Finally, after several changes of venue, we managed to bag a couple of the little varmints. Then it became a question of what to do with them. We were a couple of greenhorn city slickers who had no idea of how to clean our kill or cook and eat the little critters. As with a squirrel, not much remains after a vizcacha has been skinned and gutted. We threw the carcasses into a saddlebag to take them back to the hacienda and let the experts handle it. The pursuit of the wily vizcacha had become a far more fruitless affair than we had bargained for and we wisely decided it was time to turn our energies to other endeavors.

Though the terrain was barren and treeless Altiplano, there were trout and bird life here. I had spotted mallard ducks and pink flamingos landing in the marshy areas nearby. Small trout could be seen swimming in the shallow stream that ran through it all. The whole area had a stark and ethereal beauty about it that suffused an ethos of stillness and calm. The steep files of Andean peaks impetuously marched up on either side of the valley floor and stood like cloud shrouded sentinels high above us.

Everything was just as it should be in a void of silence and great natural peace. The sky above was a bright, blue dome through which streamed brilliant sunlight unimpeded by atmospheric obstructions. The squish and suction of horses’ hooves through the marsh and the creak of leather saddles and tack gave cadence to the silence. A giant condor soared above while in the distance, a bird loosed its lonely cry. A breeze wafted through the valley in murmurs almost unnoticed.

We paused and lunched like Inca kings on Plumrose canned beef and soda crackers washed down with achingly cold draughts of crystalline clear, pure mountain stream water. We had fishing tackle with us as well as the trusted .22, so we decided on a two-prong attack. I got the fishing tackle out and began to set up my rod and reel. I’d go fishing while Ron would hunt ducks with the .22, or so I thought.

My fishing tackle and I were old acquaintances by now so there would be no surprises. Fishing for trout in the solitude of this high Andean redoubt turned out to be a snap and so very good for the soul. The stream was clear, cold and fast running but only about two or three feet across. Sort of like a toy stream in a miniature golf course but unbounded by any artificial barriers. It came out of nowhere and meandered far into the beyond. In between, the water was as cold and pure as the glacial melt from which it sprung.

Tiny little trout, only a couple of inches long, swam in the stream. Like dark shadows, they darted in and out through the weed and rock or positioned themselves motionless above the sandy bottom facing into the current awaiting what bounty it might bring. They abounded, were everywhere and held full sway over their domain. All was natural and pristine like the second day of creation when there was still no sign of the sulling hand of man.

These pigmy mountain trout were hungry, voracious, famished. Ready to bite on any worm, lure or fly that happened their way. They were literally

itching to jump out of the water and into the frying pan if one had been presented to them. Whatever I offered, they took and unabashedly. There was no waiting around to strike. No coy probing of the bait or cautious approach to the lure. It was wham, bam, thank you, ma’am. The fish were small, but I got plenty, and that night there would be enough for a good meal for all.

I spent the rest of the afternoon squishing up and down this magical little stream in its magical hidden valley under the towering peaks of the Cordillera, casting and reeling in my catch unimpeded and content. I was at ease and abiding in the limitless natural peace of the place and the abundance of the land. You needed nothing else here. There was no one else around for miles and miles. There were no laws, no regulations, no limits, no licenses. There were no police, no tax collectors, no politicians, no game wardens, even. No enforcers. No subjugators. No armies. No military-industrial complex. You were totally free here. Free to respect the right of all nature to be as it was in this universe, at this moment. Truly. I did not want it to end, but then eventually, all things do. Night was falling, and the shadows were growing longer. Time was slowly slipping away as the day faded into evening.

The heat was being sucked out of the day, and purple pastels replaced the blazing brightness of sunlight in the cobalt blue skies above. A crisp coolness spread over my body like an Arctic breath, and I shivered in the breeze’s caress. The cold would soon be piercing and unbearable. Already the first star of the evening had appeared, heralding the arrival of the galaxies and constellations that would set the crystalline night sky ablaze with their otherworldly beauty. Day was done, and so was our labor. There was just enough time to get back to the hacienda before dark.

I retraced my route down the valley to where I’d left Ron to hunt ducks. A .22 rifle is not the proper weapon for duck hunting. So there was the possibility of plenty of surprises. We’d already seen how hard it was to hit anything with the .22 in the vizcacha episode. Even if Ron found a couple of unsuspecting ducks sitting on the ground, it would be a difficult shot to bag one. It would be virtually impossible to bring a duck down on the wing. That is why they invented shotguns.

As it turned out, Ron didn’t even bother with ducks. He went after an unsuspecting, gorgeous pink flamingo. The beautiful bird was just standing there in the marsh minding his own business when death in the form of a speeding .22 bullet ripped through its brilliant plumage and dropped him cold. Ron was proud of it, and I guess it was a good shot, but the final word here is that pink flamingos are inedible. Ron told me not to worry since he was collecting the flamingo as a specimen and planned to preserve and mount it in his study. Sort of like a latter-day Charles Darwin on the voyage of the Beagle. This in spite of the fact, that as far as I knew, he had no taxidermy experience and nothing even vaguely resembling a study in these parts.

Ron’s explanation of the why and wherefore of his deed caught me by surprise, but my reaction was mild in comparison to that of the mayordomo and the ranch hands at the hacienda when we showed up that evening with this incredible prize. However, Ron did display a certain degree of resolve and set about desiccating the corpse in preparation for mounting it. Unfortunately, Ron was no taxidermist, and the wired up carcass began to wilt and putrefy within a couple of days. The stench of the decomposing bird soon led to its unceremonious disposal on the trash heap of history outside our hovel. No one said anything. It was better just to let the whole thing go.

The end of the trip was near. It was time to go. Supplies were running low. Our stores were down to some stale bread, dried llama charqui, a little sugar, cooking oil and tea. We were tired, dirty and ready for a hot meal and shower. The time had flown by, and though only a few days had passed, it felt like it had been months since we had left civilization behind. We had lived in squalor and privation amid great, natural beauty. We’d survived. Just like the campesinos, maybe, but with one big difference. We could leave this place any time we wanted and re-enter our world of privilege and comfort while the campesinos were condemned to this existence of suffering and privation for the rest of their lives. No end in sight just more of the same, ad infinitum. It was a poignant note to leave on.

Our buddy, the company manager, would be meeting us with his truck the next day at noon on the crossroads below. From there we would be driven back into Sicuani and civilization. This meant an early departure from the hacienda before sunrise. Preparations for departure were simple and unhurried.

A modest meal was prepared. Goodbyes were exchanged between newfound friends and landscapes. Horses were rounded up. Saddles and tack were made ready for the next day. Materially, there was not much to be packed. We had come in light and were leaving even lighter. Mentally, however, our memories were crammed to the brim with thoughts and remembrances of life’s extravagant bounty and fortune. Incredibly beautiful, eternally changing, effervescent, lighter than air, these treasures were easily borne in the mind’s vaults as well as highly perishable over time.

Dawn exploded over the land the next day and the dramatic transformation from the inky black of night to the Day-Glo brilliance of early mourning, reaffirmed the ancient worship of Inti, the Inca God of the Sun. The weather promised to be clement. Maybe cold, but no blizzards were expected, and we had the extra-added luxury of a couple of the ranch hands to guide us safely to the road. This was like a bit of paid vacation for our campesino guides. They got a break from the monotony of the daily grind and routine of ranch life. We gave them more than a couple of day’s pay in Soles and threw in our surplus supplies and gear to boot.

The ride down on horseback was a slow and leisurely extraction from this otherworldly existence. The way down is always less demanding than the way up. The peaks of the Andes towered over us and surrounded us on all sides as we slipped like chameleons from one life to another. So-long. Good-bye. We would most probably never return here again in our lifetimes.

The barren, rugged beauty of the terrain intensified with every shuddering, sure-footed drop in altitude. Saddles creaked, while pots and pans and empty cans in the saddlebags, clattered. Now there was more oxygen and breathing was less labored. Sunlight beat down, unfiltered through cloudless, cobalt blue skies.

For the first time in several days, we began to feel warm. Then it was uncomfortably hot and our bodies were sweating. We stripped off our heavy parkas and scarves as we descended. Then came the sweaters and flannel shirts. We were unpeeling like onions in the sun. Breezes snuffled up the canyon from the valley floor below, cooling lathered horses and sweating riders alike.

As promised, our buddy was there at the crossroads when we arrived at the stroke of noon. His pickup loomed up like some vehicle out of a science fiction film. This was our space shuttle for the final leg of the trip back into reality. We dismounted and stretched our aching backs before loading what luggage we had in the back of the pickup. Final heartfelt farewells were exchanged with our campesino guides as they led our mounts back up onto the steep trail home. Vaya con Dios, amigos de la vía!

Our friend had been patiently waiting in the truck with the motor running. We didn’t want to delay him any longer and got in the truck for the short ride home. For us, the rutted road was like a superhighway over which we sped at a rattling, bone-jarring pace along the banks of the Vilcanota River. The crackling radio was turned up to full volume, belting out snatches of Huaynos, Boleros, and ads to “Drink Inca Kola.” Huts and ramshackle buildings, telegraph poles, cement culverts, metal bridges crossing the river here and there flashed by as more and more signs of civilization popped up along our route. The green smudge of the eucalyptus groves surrounding the Maranganí textile mill bunched up on the horizon. The village of company houses and buildings came into sight and passed in a blur.

The valley road ran snake-like through checkered plots of farmland and pastures bordered by the Vilcanota River and bounded on both sides by towering Andean ranges. Railroad tracks knifed, straight as an arrow, through the valley towards the urban sprawl of Sicuani that began to unfold in the distance. The town spread out on both sides of the river. It beckoned and grew and then finally embraced us in its tattered outskirts. We were home.

•

Michael Beede attended San Diego State University and received a B.A. in Anthropology in 1968. He served two tour in the Peace Corps in Peru (1963-65) and Venezuela from 1968-70. He returned to Venezuela in 1969 and worked for a year as a journalist on the Caracas English language daily, the Daily Journal. Then he lived and worked on Chile’s Easter Island from 1972–1975 in archaeology and monument restoration with Dr. William Mulloy of the University of Wyoming. Returning to Venezuela in 1978 he worked as a drilling fluids engineer in the petroleum industry for the next ten years. He currently resides in Venezuela where he retired In 1999 to devote himself full time to writing his memoirs.

Ah, the memories. Wonderfully written.

Would make a great buddy movie! I have one observation and a question. The observation: You all had more “fun” than we even dreamed of in Colombia. Question: Where did you get the guns?

Joanne,

Thanks for your observation and question. I agree with you that the story would make a great buddy movie but in order to adapt the story to a screenplay, I have to finish the book first. I’m in that process right now. We had a lot of “fun” no doubt about it but we also had our share of “culture shock”, trauma and let down. You will have to read the rest of the book for that. The .22 rifle we used in the infamous hunting episodes was a one-time loaner from a local friend and we never owned any guns ourselves.

I agree: this is very well written. Congratulations. Joanne- firearms for volunteers were only prohibited later. In the beginning, you could bring your own or buy in the host country.

Thank you, Lorenzo.

Michael Beede

July 14, 2019

Mary, Thanks very much for your short but to the point comment. “Up On The Mountain” is an excerpt from a book I am working on about my 1963 – 65 Peace Corps experiences in Peru. Writing this episode was like boarding a time machine that whisked me back 56 years with the clarity and feeling that I was actually there again reliving those wonderful memories. I could taste it and it was fun.

Lawrence,

Thanks for your compliments on the rendition of my “Up On The Mountain” piece. It was fun recalling and writing the episode 56 years after the fact. I don’t recall any regulations on firearms for Volunteers in Peru at the time of my service, but neither I nor any PCV I knew of ever owned a gun. The .22 rifle we used then was a one-time loaner from a local friend.

Having backpacked and even hunted vizcacha (totally unsuccessfully) in remote areas of the Bolivian Andes, I could feel and sense all of the vibrantly depicted scenes in your story…….great job! What is coming next?

Hey Rob,

So great to hear from you after such a long time. Thanks for reading my piece and your compliments on my rendition and style. It made my day. Also many thanks for putting me in touch with John Coyne who has made all this possible. What is coming next, I hope, is the completion of the book I’ve been working on of which “Up On The Mountain” is an excerpt.

I intend to resume our email communications as of now. Take care, my friend.

Rob- do you remember the PC rules for firearms in the late 60’s. I believe that when I joined it depended upon the country rules. Mexico permitted firearms so long as they were registered but Honduras did not. Unfortunately, I donated my PC rulebook from 1975 to the Kennedy Library so I can’t check.

Joanne, Reading this, my earlier descriptions of visiting remote African villages, and all the village toddlers following my prospecting crew through the African bush might not be as “romanticized” as you earlier thought. I still think of those village children, who now, 55 years later, are becoming village elders, and wonder if they remember the day “European-mahn” visited their village with his crew, and taught all the little girls how to curtsey. Fond memories. John T

Michael- It’s good to hear that this is an excerpt from a book. Make sure you let the PC community knows when it comes out. I would love to buy a copy. I found the hunting and fishing adventure refreshing and didn’t blink about the firearms since many of our Honduras foresters also did hunting and fishing. Today’s PC rulebook is more like dictionary sized and forbids almost anything imaginable. It’s crazy, baby. It’s fair to say that I would not do well in today’s PC. Oh, Rob has my email if you would like to ask any questions.

If my memory serves me, in the early days there was a strict prohibition on possession of firearms in ALL of the Africa PC projects.

With the intention of an antelope hunting trip AFTER my completion of service, whilst visiting Johannesburg I had purchased a beautiful, slightly worn Africa pattern rifle, BRNO Mauser, 7x57mm cal, and had it shipped to the Malawi Police for safekeeping in the meantime. The police were happy to help, and asked all about my hunting plans, in Mocambique.

My last PC week I asked the police to deliver my rifle to the PC Office, in Blantyre, which we all found was very disapproving. Naughty, naughty. I pointed out that THEY were in possession, not me. We finally got that ironed out.

But the war was already going on in Mocambique, and a week before I was scheduled to board the train to Beira, rebels blew up the RR line. The police and I concluded that wandering around with a rifle, with rebels and Portuguese-Africa troops everywhere, might be risky. With friendly consolation from the police constable, we boxed up my rifle and shipped it home. My much-anticipated hunting trip never happened.

I still have that rifle, with it’s set triggers, folding leaf sights, and sling swivel out on the barrel, and every now and then take it out for a look-see, and some regrets about the way things unfolded. John Turnbull

Michael- what a wonderful writer you are–I was with you all the way, shivering and all Many years ago, I was invited to join friends to trek up the Himalayas. Your story brought back memories galore. From the whiteout, dung burning, and trying to stay warm in the sleeping bag all came crashing out of my memory. Thanks for the enjoyment!!

Togo, West Africa 90-92ish

An enjoyable read, my Brother – keep ‘em coming! And I’d like to think that your adeptness at dealing with little rodents began its climb way back when, while pushing a much younger me in my stroller through the sleepy streets of Coronado.

You’re welcome!!

Ricardo Montalban

Caramba. Miguel Beede. I ran across your article and it was wonderful. What a great writer you are. Candy, of Candy and Jay, asked about you, and I told her I had no idea where you were. Candy and I keep in touch. She is in Chicago and I in Lakeland, Florida. We both reminisce about our PC days in Venezuela. Hard to believe it was over 50 years ago. You brought all those memories flooding back. Fernando died a few years ago. Tu amiga, Alice Castro Padilla Bradshaw . And was that Rod from our PC group? Stay safe during these trying times.

Michael…where have you been? You are part of the Arias family. Last time was your visit to my Response site in the Darien in Panama, the Indios still ask about. I am still in Panama, love it here. Abrazos to the Venezuela group, the first in-country training group for Peace Corps Latin America! Animo Mijo…I expect to hear from you!

Bob

Hi Michael, where can I purchase a copy of your book?

Hello Michael,

I was searching the internet re: the Peace Corp and Peru, as my late father served during that same time and location. Curious if you knew a Paul H. May?? I just took my boys to Cuzco and Machu Picchu and would love to share more of their grandfather with them. Please let me know where I can order your book, sounds fascinating. Best wishes.

Michael, Bob Brannon here. My wife,Maryellen Enright, who died in 1999, was the Cusco Office Secretary/Manager, from most of 1964 thru 1965.

As luck would have it, I found her letters to her mother, one a week or so giving lots of detail about what was happening in PC in Cusco, Puno, etc and in her life.

I liked your article/story.

How is your memoir coming. Would like to get a copy.

I was a PCV in Lima mostly teachindgat two Universities 1965/66.

Bob Brannon

Me emocioné mucho cuando mi hijo James me mostró que estabas escribiendo acerca de Perú. Me gustaría saber cuando lo termines, donde comprarlo. Perdona soy tu amiga Maruja de Sicuani.

Have I found the Mike Beede, the Anthropology major from SDSU. If so, please respond.

Mike,

Please use my email to respond, if possible…sschatzl@sdsu.edu

Thanks,

Steve